Published online May 21, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i19.2430

Revised: September 23, 2011

Accepted: April 12, 2012

Published online: May 21, 2012

The case of a 52-year-old woman with a past history of thymoma resection who presented with chronic diarrhea and generalized edema is the focal point of this article. A diagnosis of Giardia lamblia infection was established, which was complicated by protein-losing enteropathy and severely low serum protein level in a patient with no urinary protein loss and normal liver function. After anti-helmintic treatment, there was recovery from hypoalbuminemia, though immunoglobulins persisted at low serum levels leading to the hypothesis of an immune system disorder. Good’s syndrome is a rare cause of immunodeficiency characterized by the association of hypogammaglobulinemia and thymoma. This primary immune disorder may be complicated by severe infectious diarrhea secondary to disabled humoral and cellular immune response. This is the first description in the literature of an adult patient with an immunodeficiency syndrome who presented with protein-losing enteropathy secondary to giardiasis.

- Citation: Furtado AK, Cabral VLR, Santos TN, Mansour E, Nagasako CK, Lorena SL, Pereira-Filho RA. Giardia infection: Protein-losing enteropathy in an adult with immunodeficiency. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(19): 2430-2433

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i19/2430.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i19.2430

Protein-losing enteropathy (PLE) is a rare syndrome of gastrointestinal protein loss that may complicate a variety of diseases. The diagnosis of PLE should be considered in patients with hypoproteinemia, especially hypoalbuminemia, after other causes have been excluded, such as malnutrition, proteinuria, and impaired protein synthesis. The diagnosis is most commonly based on the determination of fecal α-1 antitrypsin clearance, though scintigraphy (technetium-99m-labeled human serum albumin scan-99mTc-HSA) aids in localizing the site and quantifying enteric protein loss[1].

The pathogenic mechanism can be divided into erosive gastrointestinal disorders, nonerosive gastrointestinal disorders, and disorders involving increased central venous pressure or mesenteric lymphatic obstruction[1]. Although not extensively studied, certain enteric infections (Salmonella, Shigella, Rotavirus, and Giardia lamblia) can also damage the intestinal mucosa leading to excessive protein loss, particularly in an immunocompromised host[2,3].

Giardia lamblia is a protozoan that frequently infects the gut and plays an important role in the public health of developing countries, such as Brazil[4]. Transmission occurs through oral-fecal contact or intake of contaminated water and food by the infecting forms (cysts or oocysts). Although normally presenting with mild symptoms, such as cramps and chronic diarrhea, more severe complications can take place and malabsorptive syndrome may develop[5]. In this case report, severe giardiasis is illustrated in an adult patient with a past history of thymoma who developed PLE, a rare complication that particularly affects infants.

A 52-year-old black woman was referred to our hospital because of chronic diarrhea and generalized edema. She had gained 10 kg over the last year because of peripheral edema, and complained about asthenia and fatigue. She had no abdominal pain, fever or stool bleeding. Two years before the event, while under investigation for chronic cough and chest pain, the diagnosis of a type AB thymoma was made according to World Health Organization classification and she underwent a sternal thymectomy. Anatomopathological analysis showed no signs of capsular, vascular or lymphatic invasion.

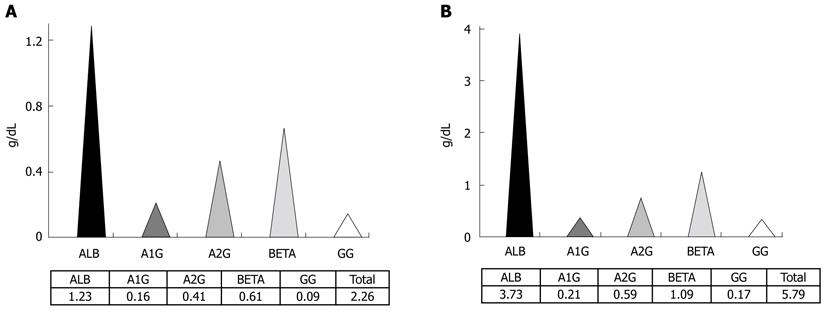

The patient presented mild steatorrhea on a semi-quantitative stool analysis, negative proctoparasitologic examination and severe hypoproteinemia on serum protein electrophoresis (Figure 1A). A hepatic cause of hypoproteinemia was ruled out by clinical and laboratory parameters and urinary sedimentary analysis was normal with no proteinuria. There was altered coagulation testing related to vitamin K deficiency, normocytic normochromic anemia, and normal leucocyte and platelet count.

She was submitted to 99mTc-HSA which demonstrated mild protein loss from the small bowel though no specific site was able to be localized. She had a normal colonoscopy and an upper digestive endoscopy that showed moderate duodenitis. On duodenal biopsy, there were structures identified as Giardia lamblia, moderate non-specific active chronic duodenitis, and preserved villi:crypt ratio. Giardiasis was not attributed at first to be the cause of the enteric protein loss. In subsequent investigations, anterograde enteroscopy was undergone, demonstrating only non-specific duodenal and jejunal lesions. No remarkable findings were verified on histological samples.

Nevertheless, after anti-helmintic treatment with oral metronidazole, she ended up recovering from diarrhea and edema. No signs of enteric protein loss were verified by scintigraphy and serum albumin level normalized, though hypogammaglobulinemia persisted (Figure 1B).

On evaluation of intermittent asthma and rhinitis since childhood and recurrent pneumonia, antibody deficiency was diagnosed, including immunoglobulins IgA, IgE, IgG and IgM. Cytometry analysis of peripheral blood lymphocytes revealed a marked decrease in CD19+ B-cells. Bone marrow biopsy demonstrated a chromosome 9 inversion with chromosome 16 deletion [46,XX,inv(9),del(16)(q22)] with unknown significance and no additional important findings. Based on previous history of thymoma and current hypogammaglobulinemia, the diagnosis of Good’s syndrome (GS) was made even though no evidence of cell-mediated immune defects was verified.

Giardia lamblia is a flagellated intestinal protozoan with oral-fecal transmission. Infection takes place in the proximal small gut, especially duodenum, where motile trophozoites live adhered to enterocytes[5].

Examination of concentrated, iodine-stained wet stool preparations and modified-trichrome-stained permanent smears has been the conventional approach to the diagnosis. Despite three negative stool samples, the diagnosis of giardiasis could be made by duodenal biopsy in this case report. In fact, cysts and trophozoites are present only intermittently in feces, offering a low sensitivity of approximately 50%, even with examination of multiple specimens. Identification of trophozoites within small intestinal biopsy specimens requires careful examination of multiple microscope fields to ensure accuracy[6], although on direct sampling of duodenal contents (e.g., duodenal aspiration or the “string test”), sensitivity can be improved to approximately 80%. Therefore molecular tests based on enzyme linked immunosorbent assay or direct immunofluorescent antibody microscopy should be the first diagnostic test to be performed because of high accuracy, with sensitivities greater than 90% and specificities approaching 100%.

Worldwide, Giardia affects infants more commonly than adults and has different pathogenicity in experimental human infections. Infected patients, especially those immunocompromised, may present malabsorptive diarrhea of yet unknown mechanism. Trophozoites adhere (perhaps by suction) to the epithelium of the upper small intestine, using a disk structure located on their ventral surface. There is no evidence that trophozoites invade the mucosa. On biopsy, pathologic changes range from an entirely normal-appearing duodenal mucosa (except for adherent trophozoites) to severe villous atrophy with a mononuclear cell infiltrate that resembles celiac sprue[7].

The severity of diarrhea appears to correlate with the severity of the pathologic change[6]. In fact, the host immune response plays a critical role in limiting the severity of giardiasis; this is mediated by humoral immune response, both systemic (IgM and IgG) and mucosal (IgA). Certain populations, including children younger than 2 years of age and patients with hypogammaglobulinemia, are more likely to develop serious disease. When infected with Giardia, individuals with common variable immunodeficiency develop severe, protracted diarrhea and malabsorption with sprue-like pathologic changes that resolve with treatment[3] such as immunoglobulin replacement[6]. The importance of a cellular immune response is yet to be determined. On immune reconstitution, severe inflammatory changes and villous atrophy develop in the intestine, suggesting that the immune response to infection may contribute to pathology, although severe infections that are resistant to treatment or an increased frequency of giardiasis have been noted only rarely in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome[7].

PLE is a rare complication associated with Giardia infection, as formerly described in infants[1-3]. As illustrated in this article, this infection may cause severe enteric mucosal damage that leads to an inflammatory process and exudative protein loss. Sometimes, especially when there is associated lymph leakage, secondary immunodeficiency may develop as decreases in serum lymphocytes and hypogammaglobulinemia occur[1].

As previously mentioned, although PLE is better diagnosed by the determination of fecal α-1 antitrypsin clearance because of high accuracy of the method, scintigraphy was the option chosen for the diagnosis in this case and it could localize protein loss from the small gut at non-specific sites. 99mTc-HSA scan possesses high sensitivity and specificity; it may demonstrate the site and semi-quantify protein loss, despite some false positives resulting from active gastrointestinal bleeding and in vivo breakdown of 99mTc-HSA, yielding free pertechnetate from radiolabeling[8]. The former is easily excluded by fecal occult blood examination and the latter by the absence of stomach or thyroid visualization.

At first, the hypothesis of hypogammaglobulinemia secondary to gut protein loss was put forward for this patient since severe universal hypoproteinemia was verified in pre-treatment serum protein electrophoresis. Nevertheless, after metronidazole was instituted, every serum protein fraction increased but gammaglobulin remained very low. This led to the belief that she possessed an immune disorder, which could explain the advanced enteropathy caused by Giardia infection and the persistent hypogammaglobulinemia in spite of medical treatment.

Patients with thymoma may suffer from specific types of paraneoplastic syndrome or remote effects of cancer which have underlying autoimmunity origins. They include myasthenia gravis, pure red cell aplasia, and hypogammaglobulinemia (Good’s syndrome), with approximate occurrence of 30%, from 1.6% to 5%, and from 3% to 6%, respectively. Autoimmunity to B lymphocyte lineage causes severe deficiency in B lymphocytes and hypogammaglobulinemia, resulting in acquired immunodeficiency vulnerable especially to bacterial infection. Although most paraneoplastic syndromes have been documented to recover after tumor resection, some previous case reports seem to indicate that hypogammaglobulinemia without improvement can last even after tumor resection for as long as 9 years[9].

GS is a rare association of thymoma and immunodeficiency first described more than 50 years ago by Dr. Good. The diagnosis of thymoma usually precedes the diagnosis of hypogammaglobulinemia and other clinical manifestations, such as infection or diarrhea, in almost half of the cases. Recurrent sinopulmonary infection is commonly the first clinical manifestation followed by chronic diarrhea, the mechanism of which is not identified in the majority of cases, although bacteria, such as Salmonella spp., and other pathogens, like cytomegalovirus and Giardia lamblia might the etiological factor[9,10].

GS, in contrast to other primary immunodeficiency disorders such as common variable immunodeficiency disease, usually affects adults in the fourth or fifth decade of life, equally male and female, and almost always associated with hypogammaglobulinemia. Although there are no formal diagnostic criteria for this disorder, GS is characterized by low to absent B cells in the peripheral blood, hypogammaglobulinemia, and variable defects in cell-mediated immunity; with a CD4 lymphopenia, an inverted CD4/CD8+ T-cell ratio and reduced T-cell mitogen proliferative responses[4]. In clinical practice, as illustrated in this report, serum flow lymphocytometry shows absence of B lymphocytes, discrete low CD4 T lymphocyte count and inverted CD4/CD8 ratio[9-11].

It has long been known that giardiasis is a frequent infection of the gastrointestinal tract, especially in infants and in developing countries, typically manifesting as chronic diarrhea, abdominal cramps and fatigue. The diagnosis may be challenging as conventional methods of stool examination can lack sensitivity. In cases of strong clinical suspicion, serum serology is of great value when available, though upper digestive endoscopy is a reliable tool to demonstrate degree of duodenal damage and direct diagnosis can be made through histological sample. As far as we know, this is the first time in the literature that Giardia infection complicated with PLE has been reported in an adult patient. In fact, whenever severe giardiasis occurs in adulthood, immunodeficiency should always be kept in mind because of humoral IgA-mediated immunological pathogenicity, and clinical investigation should be directed towards this suspicion, even though rare in cause.

Peer reviewer: Greger Lindberg, MD, PhD, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Karolinska University Hospital, K63, Stockholm, SE-14186, Sweden

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Umar SB, DiBaise JK. Protein-losing enteropathy: case illustrations and clinical review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:43-49; quiz 50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Braamskamp MJ, Dolman KM, Tabbers MM. Clinical practice. Protein-losing enteropathy in children. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;169:1179-1185. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Dubey R, Bavdekar SB, Muranjan M, Joshi A, Narayanan TS. Intestinal giardiasis: an unusual cause for hypoproteinemia. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2000;19:38-39. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Mascarini LM, Donalísio MR. [Giardiasis and cryptosporidiosis in children institutionalized at daycare centers in the state of São Paulo]. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2006;39:577-579. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Huston CD. Chapter 109: Intestinal protozoa-Giardia lamblia. Sleisenger and Fordtran’s gastrointestinal and liver disease: pathophysiology/diagnosis/management. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Inc 2006; 1911-1914. |

| 6. | Roxström-Lindquist K, Palm D, Reiner D, Ringqvist E, Svärd SG. Giardia immunity--an update. Trends Parasitol. 2006;22:26-31. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Solaymani-Mohammadi S, Singer SM. Giardia duodenalis: the double-edged sword of immune responses in giardiasis. Exp Parasitol. 2010;126:292-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chen YC, Hwang SJ, Chiu JS, Chuang MH, Chung MI, Wang YF. Chronic edema from protein-losing enteropathy: scintigraphic diagnosis. Kidney Int. 2009;75:1124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kelleher P, Misbah SA. What is Good's syndrome? Immunological abnormalities in patients with thymoma. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:12-16. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Kelesidis T, Yang O. Good's syndrome remains a mystery after 55 years: A systematic review of the scientific evidence. Clin Immunol. 2010;135:347-363. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Kitamura A, Takiguchi Y, Tochigi N, Watanabe S, Sakao S, Kurosu K, Tanabe N, Tatsumi K. Durable hypogammaglobulinemia associated with thymoma (Good syndrome). Intern Med. 2009;48:1749-1752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |