Published online Jan 21, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i3.379

Revised: September 2, 2010

Accepted: September 9, 2010

Published online: January 21, 2011

AIM: To study the computed tomography (CT) signs in facilitating early diagnosis of necrotic stercoral colitis (NSC).

METHODS: Ten patients with surgically and pathologically confirmed NSC were recruited from the Clinico-Pathologic-Radiologic conference at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taoyuan, Taiwan. Their CT images and medical records were reviewed retrospectively to correlate CT findings with clinical presentation.

RESULTS: All these ten elderly patients with a mean age of 77.1 years presented with acute abdomen at our Emergency Room. Nine of them were with systemic medical disease and 8 with chronic constipation. Seven were with leukocytosis, two with low-grade fever, two with peritoneal sign, and three with hypotensive shock. Only one patient was with radiographic detected abnormal gas. Except the crux of fecal impaction, the frequency of the CT signs of NSC were, proximal colon dilatation (20%), colon wall thickening (60%), dense mucosa (62.5%), mucosal sloughing (10%), perfusion defect (70%), pericolonic stranding (80%), abnormal gas (50%) with pneumo-mesocolon (40%) in them, pericolonic abscess (20%). The most sensitive signs in decreasing order were pericolonic stranding, perfusion defect, dense mucosal, detecting about 80%, 70%, and 62.5% of the cases, respectively.

CONCLUSION: Awareness of NSC and familiarity with the CT diagnostic signs enable the differential diagnosis between NSC and benign stool impaction.

- Citation: Wu CH, Wang LJ, Wong YC, Huang CC, Chen CC, Wang CJ, Fang JF, Hsueh C. Necrotic stercoral colitis: Importance of computed tomography findings. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(3): 379-384

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i3/379.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i3.379

Necrotic stercoral colitis is a necrotic process that occurs in stercoral colitis (SC), caused by fecal impaction that results in pressure ulceration and regional necrosis. Perforation is rare, but has a mortality rate of 32%-57%[1]. Early diagnosis with aggressive bowel cleansing and disimpaction may decrease the pressure and lessen the likelihood of ulceration of the colon[2]. Fecal impaction frequently occurs in elderly patients, and those who are bed-ridden for a prolonged period of time.

Most patients present to the emergency room (ER) with an acute abdomen. Their physical examinations and laboratory data are often unreliable. Moreover, the peritoneal signs are often nonspecific and might be attributed to diverticulitis, which is more common in elderly patients[3]. Computed tomography (CT) is readily available and is not operator-dependent; therefore, abdominal CT is often requested by emergency physicians to evaluate patients with acute abdominal conditions.

Very little has been published on NSC in the radiology literature[3]. We reviewed the CT findings of 10 patients with NSC from our hospital, to call attention to this potentially fatal condition.

This work has been carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2000) of the World Medical Association. This study was approved ethically by Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (98-0044B).

Between November 2002 and August 2009, ten patients with surgically and pathologically confirmed NSC were recruited from the Clinico-Pathologic-Radiologic conference at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taoyuan, Taiwan. We reviewed their abdominal radiographs, CT images, and medical records retrospectively.

All of these patients underwent CT examinations of the abdomen and pelvis before surgical exploration, while they stayed in the ER. CT examinations were performed by four-detector CT (LightSpeed QX/i Scanner, General Electric Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI, USA). Helical CT images were acquired using either 7- or 5-mm slice collimation, reconstruction interval of 5 mm, pitch of 1.5-2, 120 kV, and 200-240 mA. One hundred milliliters of intravenous (IV) contrast agent was used routinely.

Several CT findings of fecal impaction in the colon, thickening of the colon wall, and pericolonic stranding indicated SC, whereas the presence of extraluminal gas bubbles or an abscess suggested that perforation had occurred[2].

The CT examinations were retrospectively reviewed by two independent board-certified abdominal radiologists who were blinded to the CT official reports and the surgical and pathologic findings. They viewed the CT images on a picture archiving and communication system (PACS) independently and discussed the findings until consensus was reached. If consensus could not be reached, a third abdominal radiologist was consulted. All abdominal radiographs were reviewed for abnormal gas. They were also requested to determine the presence or absence of the CT features of NSC, including location of fecal impaction, proximal colon dilatation, colon wall thickening, dense mucosa, mucosal sloughing, perfusion defect, pericolonic stranding, pericolonic abscess, and abnormal gas with or without pneumo-mesocolon. Vascular ischemic colitis was excluded based on patency of the inferior mesenteric artery and vein.

The individual CT signs were defined as follows - Fecal impaction: distended colon with much feces or packing of dehydrated fecaloma in the colon; Proximal colon dilatation: a distended left-sided colon with a cylindrical shape and cross-sectional diameter > 6 cm; Colon wall thickening: regional wall thickness > 3 mm in the obstruction site; Dense mucosa: increased mucosal lining density on pre-contrast CT; Mucosal sloughing: mucosa dislodged into the lumen; Perfusion defect: discontinuity of the enhancement of colon mucosa or apparently decreased enhancement as compared with adjacent small bowel loops; Pericolonic stranding: increased streaks of pericolonic fat; Pericolonic abscess: pericolonic loculated fluid or mottled substance; Abnormal gas: gas migrating into or beyond the colon wall as pneumoperitoneum or pneumoretroperitoneum, i.e. pneumo-intestinalis coli: gas entrapped in the mural wall; pneumo-mesocolon: gas confined inside the mesocolon; and portal vein gas: air leakage into the porto-mesenteric vessels.

Six men and four women aged 39-88 years (mean, 77.1 years) were studied (Table 1). All of the patients presented to our ER with acute abdomen. Chronic constipation and systemic medical disease were the common clinical problems in these patients. Abdominal discomfort was not greatly improved after local removal of impacted feces by digital evacuation or fleet enema. On arrival at the ER, two patients (20%) presented with a low grade fever (< 38.5°C), two (20%) presented with peritoneal signs, and seven (70%) presented with leukocytosis with one other at borderline criteria of leukocytosis. Three patients (30%) arrived at the ER with hypotensive shock (systemic blood pressure < 90 mmHg). Surgical intervention was indicated for all of the patients. Seven of the patients died; thus, the mortality rate was 70%. Among these seven patients, three died within 1 wk, highlighting the rapidly progressive course of the disease.

| No. | Age (yr)/sex | sBP | BT | Hx | Cor | PS | WBC | TI | Fe | Pe | Operation findings | Pathology | Outcome |

| 1 | 76/M | 183 | 38.4 | + | DM, HTN | - | 22.2k/89 | 5’30’’ | RS | No | Ischemic change from sigmoid to rectum with necrotic mucosa | Ischemia necrosis with mucosal sloughing | Alive |

| Arrhythmia | |||||||||||||

| 2 | 86/M | 130 | 34.4 | + | CAD | - | 45.6k/72 | 2’30” | S | S | Necrosis of descending and sigmoid colon with a 2-cm perforation | Perforating ulcer with transmural necrosis | Dead, 1 d after CT |

| RF | |||||||||||||

| 3 | 79/F | 147 | 36.1 | + | DM | - | 15.3k/76 | 7 d | D | D | Necrosis of nearly entire colon, with a 1.7-cm perforation | Mucosal ulcer with perforation | Dead, 19 d after CT |

| 4 | 87/M | 158 | 35.6 | + | HTN | + | 14.4k/90 | 4’40” | RS | S | A 2-cm perforator 2 cm proximal to the recto-sigmoid colon cancer | Transmural necrosis with a 2.1 cm perforator | Alive |

| 5 | 80/F | 120 | 33.6 | + | HTN | - | 3.6k/67 | 24’30” | S | S | Nearly entire colon necrosis with a 5-cm × 3-cm perforator at sigmoid colon | Ulcerative hole with transmural necrosis at sigmoid colon | Dead, 5 d after CT |

| 6 | 70/F | 145 | 36.4 | + | DM | - | 13.3k/80 | 15’40” | RS | No | Necrosis of distal ileum and entire colon | Transmural necrosis of bowel wall | Dead, 47 d after CT |

| 7 | 88/F | 81 | 35.0 | + | - | - | 4k/38 | 3’ | RS | S | 2 small perforators at proximal sigmoid colon | Gangrenous change with transmural necrosis of sigmoid colon | Dead, 8 d after CT |

| 8 | 39/M | 64 | 38.0 | NA | ESRD | + | 9.9k/79 | 26’ | RS | No | Ischemic patches over sigmoid colon with impending perforation | Ischemic and gangrenous change of the sigmoid coon | Dead, 3 d after CT |

| 9 | 83/M | 158 | 37.0 | NA | ARDS, HF HTN, COPD | - | 17k/93 | 11’ | RS | No | Ischemic change of small bowel and sigmoid colon | Transmural necrosis of sigmoid colon and mucosal necrosis of small bowel | Dead, 11 d after CT |

| 10 | 83/M | 64 | 35.3 | + | CAD, HTN | - | 46k/83 | 10’ | RS | No | Patch necrosis of the T and D colon | Gangrenous change of the T and D colon | Alive |

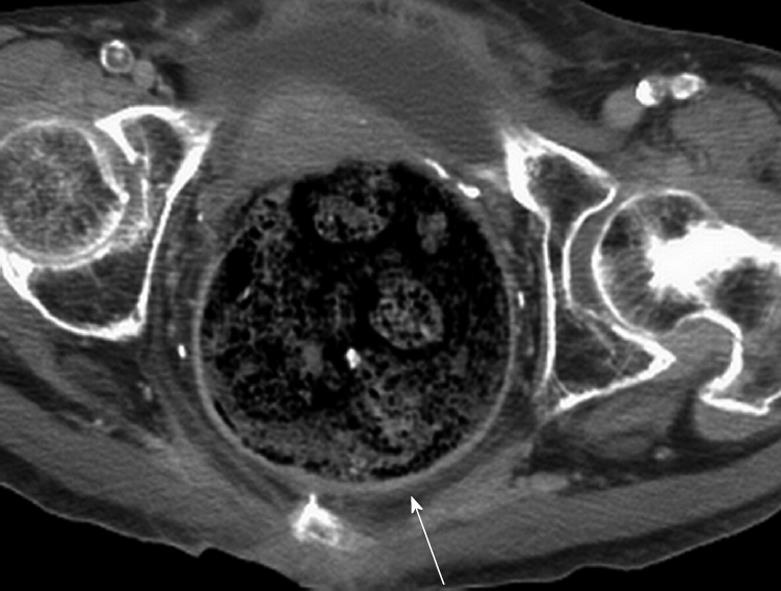

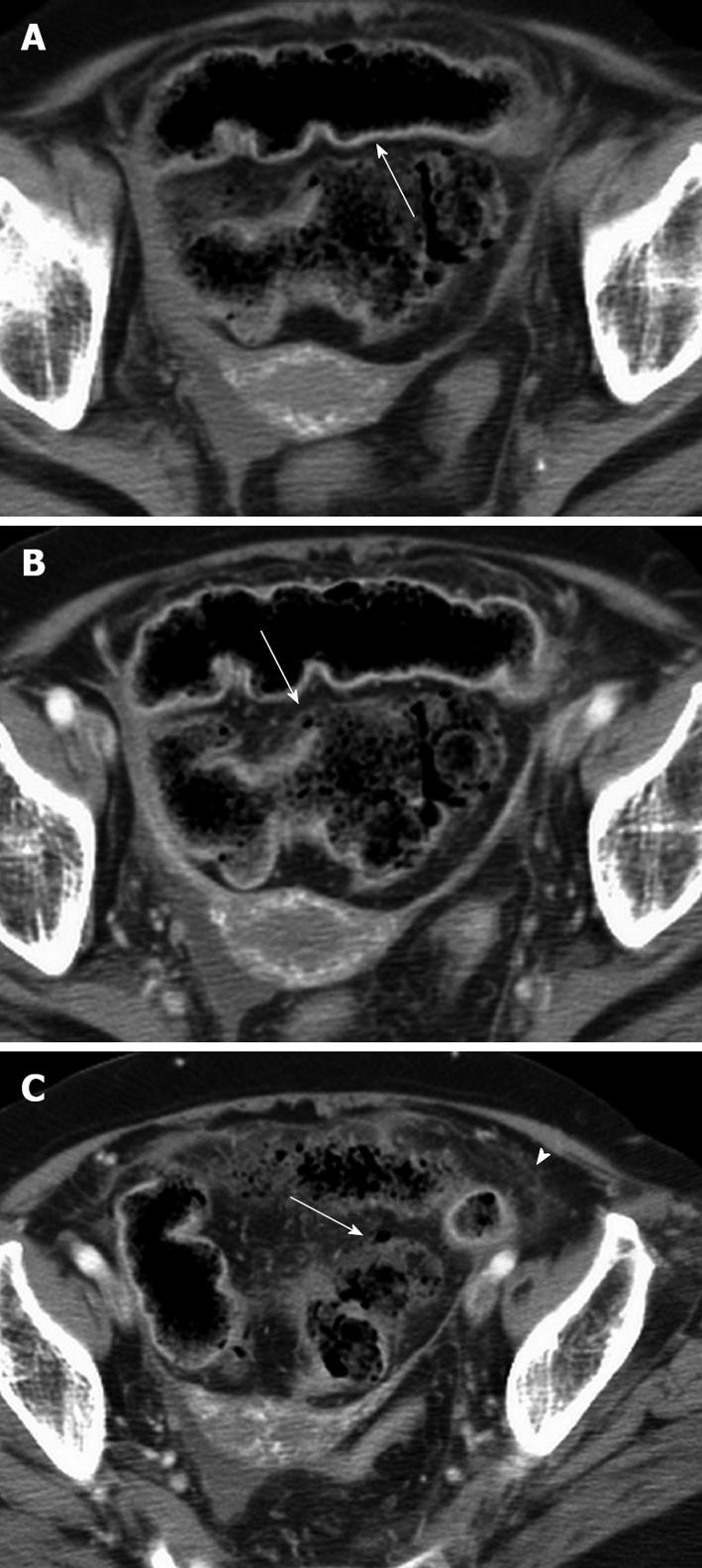

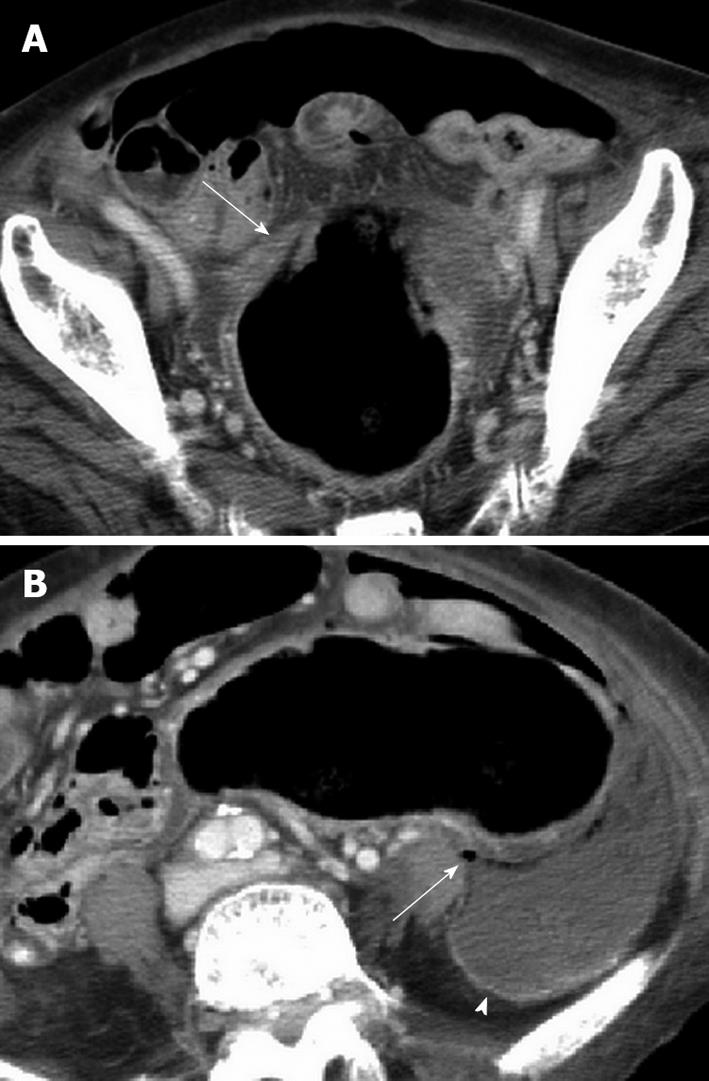

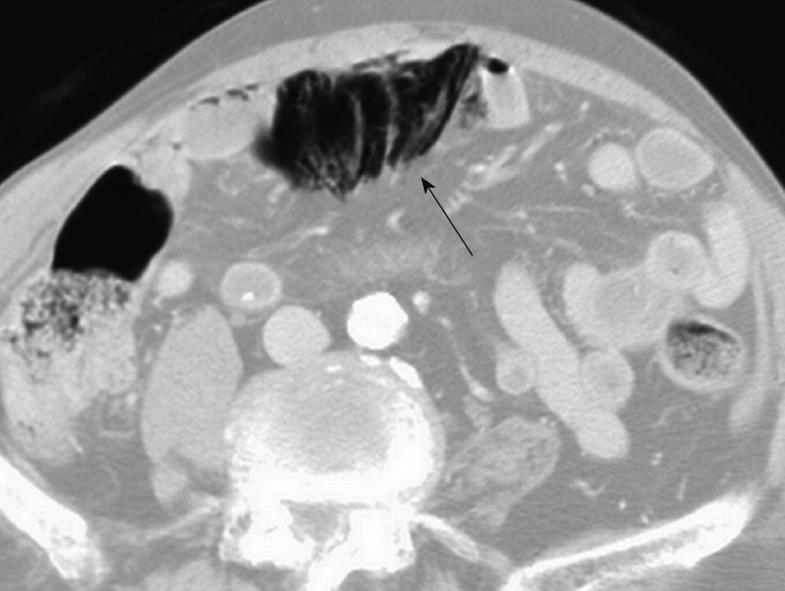

The imaging findings of NSC are listed in Table 2. CT examination revealed fecal impaction at the sigmoid colon in nine patients (90%) and at the distal descending colon in one (10%). Proximal colon dilatation was found in two patients (20%). Colon wall thickening (Figure 1) occurred in six patients (60%), dense mucosa (Figure 2A) in five (62.5%), mucosal sloughing (Figure 3A) in one (10%), and colon mucosal perfusion defect (Figure 2B) was found in seven (70%) patients. Pericolonic stranding (Figure 2C) was identified in eight patients (80%), and pericolonic abscess formation (Figure 3B) was observed in two (20%) patients. Abnormal gas was present in five patients (50%): pneumo-mesocolon in two (40%, Figure 4), and one patient (20%) with pneumoperitoneum was identified by radiograph.

| No. | Radiographic abnormal gas | CT signs | ||||||||||

| Fecal impaction | Obstructive site | Proximal dilatation | Wall thickening | Dense mucosa | Mucosal sloughing | Perfusion defect | Pericolonic stranding | Abnormal gas | Pneumo-mesocolon | Abscess | ||

| 1 | N | Y | RS | N | N | NA | N | Y | Y | N | N | N |

| 2 | Y | Y | S | N | Y | NA | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N |

| 3 | N | Y | D | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | N |

| 4 | N | Y | RS | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 5 | N | Y | S | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

| 6 | N | Y | RS | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N |

| 7 | N | Y | RS | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| 8 | N | Y | RS | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N |

| 9 | N | Y | RS | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | N |

| 10 | N | Y | RS | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N |

| Frequency | 1/5 (20%) | 10/10 (100%) | 9/10 (90%) | 2/10 (20%) | 6/10 (60%) | 5/8 (62.5%) | 1/10 (10%) | 7/10 (70%) | 8/10 (80%) | 5/10 (50%) | 2/5 (40%) | 2/10 (20%) |

| κ-value | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.4 | 0.714 | 0.615 | 0.286 | 0.737 | 0.8 | 1 | 1 |

Dense mucosa was evaluated with pre-contrast CT scanning in 8 of the patients who had undergone scanning of the lower abdomen. Dense mucosal lining conforming to the colon wall was differentiated from the fecalith which presented as clustered masses in the lumen with a calcified surface and gas in between.

Inter-observer agreement is shown in Table 2. Agreement was good to excellent for all signs except wall thickening and perfusion defect. Disagreement occurred with respect to wall thickening in three patients, perfusion defect in four, dense mucosa in one, mucosal sloughing in one, pericolonic stranding in one, and abnormal gas in one patient. Consensus was generally achieved following an open discussion and the opinion of a third radiologist when necessary.

Stercoral ulcer with perforation was first described by Berry in 1894, and to date, fewer than 150 cases have been reported[4]. The incidence of perforated stercoral ulcer at autopsy ranges from 0.04% to 2.3%. Pre-mortem diagnosis is even less frequent, which suggests that the incidence of this condition is often underestimated[3]. One study reported that stercoral perforation of the colon was found in 0.5% of all surgical colorectal procedures, 1.2% of all emergency colorectal procedures, and 3.2% of all colonic perforations[5].

Fecal impaction and perforation occur most often in the sigmoid colon. The sigmoid colon is the narrowest region of the entire colon, and passage of stools with a more solid consistency can be difficult. In such cases, fecaloma exerts localized pressure on the walls of the sigmoid colon, the area with the most precarious vascular supply[6], especially the vascular region known as Sudeck’s point. Prolonged localized pressure and ischemia can give rise to pressure ulceration[7,8].

Distention predisposes the colon to insufficient perfusion, leading to slight, moderate, or severe ischemic lesions[9]. Ischemic colitis will occur when intraluminal pressure exceeds 35 cm H2O for hours[10]. Maurer et al[5] have postulated that colonic dilatation and the presence of multiple fecalomas indicate additional stercoral ulceration and carry the risk of secondary perforation. This view was supported by Huang et al[11] by visualization of stercoral ulceration during intraoperative colonoscopy.

Chronic constipation (n = 8) and systemic disease (90%, n = 9) were the common clinical problems of the patients in this study, some of them (50%, n = 5) presented with multiple necrotic foci involving long segmental bowel that spanned the territory of the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries. It is probable that long-term systemic disease weakens the colon, while stool impaction causes bowel dilatation and increases wall tension, which worsens perfusion insufficiency and leads eventually to necrosis and potentially to fatal perforation. Unfortunately, the early clinical signs such as fever (20%, n = 2), peritoneal signs (20%, n = 2), and leukocytosis (70%, n = 7) are insufficient to diagnose this severe condition in order to prompt appropriate intervention in these patients.

Obstructive colitis differs from colonic cancer with marginal ulceration at aspects of normal mucosa distal to cancer and, frequently, centimeters immediately proximal to the carcinoma are free of ulceration and inflammation[12]. As an example of this, NSC was diagnosed in our case number 4.

Fecal impaction was present in all our patients and was located mostly at the sigmoid colon (90%, n = 9), which was highly correlated with surgical findings and a result which agrees with other studies. Proximal dilatation was observed in two patients (20%), and was less frequent than we expected. It is possible that the colon could have ruptured prior to the CT scan, thus relieving the luminal pressure. This could also be due to the possible fulminant course which did not allow time for the colon to dilate. None of these two patients with proximal colon dilatation showed abnormal gas that would have indicated whether the colon had ruptured. Probably owing to absence of proximal colon dilatation in NSC, clinicians underestimate the stool impaction.

Colon wall thickening (60%, n = 6) is an indicator of stercoral colitis caused by edema or acute inflammation. Dense mucosa as a result of mucosal hemorrhage has been reported to be a sign of ischemic bowel[13,14]. This was one of the most frequently observed signs of NSC and occurred in 62.5% (5 of 8) of our cases. Mucosal sloughing (10%, n = 1) and perfusion defect (70%, n = 7) indicated status of ischemia progressing to infarct of the colon. The radiologists’ disagreement over wall thickening and perfusion defect may have been the result of subtle and localized changes. These findings indicate that the CT signs of NSC are not obvious, and that radiologists must be aware of the signs to make an early diagnosis. Pericolonic fat stranding was the most frequent CT sign of NSC observed in our patients (8 of 10, 80%). Intraoperative findings indicated that pericolonic fat stranding was the result of pericolonic inflammation and edema. The pericolonic reaction was most likely the cause of the intolerable abdominal pain experienced by these patients.

NSC with abnormal gas (50%, n = 5) often appears on CT scans as small gas bubbles in the proximity of the colon wall: pneumo-intestinalis coli or pneumo-mesocolon. This is usually undetected by radiography and differs from gastroduodenal perforation that usually presents massive pneumoperitoneum. Intraoperative findings indicate that the perforation can be temporarily plugged by a fecaloma. In our sample, a standing radiograph was not often obtained, partly because pneumoperitoneum was not suspected clinically, and the elderly patients were usually in a weakened state that impeded their assuming a standing posture. Pneumo-mesocolon was not always evident on the radiograph because it was obscured by the presence of a lot of fecal material in the abdomen. This explains why only one (20%) of five cases with abnormal gas was detected by radiography. Thus, abdominal CT, with meticulous searching for signs of abnormal gas, is required. Pericolonic abscess formation was seen in two (20%) of our patients. When the NSC is perforated, the viscous nature of the fecal material causes it to further impede the peritoneum with soiling.

NSC differs from other colitis by absence of diarrhea clinically. It can be confirmed by intraoperative and histological findings[5]. At surgery, stercoral ulcers and perforations are usually found on the anti-mesenteric side; ulcerations usually have sharp margins and measure 1-10 cm, and are occasionally multiple. Histological findings include sharp demarcation without undermining at ulcer margins, and transmural necrosis at the perforated site. Treatment is usually resection of the affected bowel, colostomy, and Hartmann’s procedure[1,5].

Typically, only the more severe cases in this sample would have been discussed at the conference, and this resulted in a high mortality rate among our patients (70%; 7/10, which is higher than previously reported[1]).

In the elderly and in nursing home patients, ascites associated with liver cirrhosis or malnutrition is often encountered. This could obscure the significance or specificity of pericolonic fluid accumulation for colonic pathology. Thus, we did not investigate this factor for NSC.

This retrospective study consisted of a small population of patients with NSC; thus, the statistical significance and likelihood ratios of each CT sign for NSC could not be determined appropriately. Owing to the nature of the retrospective study, some important clinical data and imaging were unavailable. This study aimed to alert clinicians to the CT findings of NSC, a potentially fatal condition. A further study with a larger number of patients is needed to validate the accuracy of our CT findings.

In summary, elderly patients with a history of chronic constipation and systemic disease, presenting with fecal impaction and acute abdomen with indeterminate leukocytosis, are at risk of NSC. CT is justified to be suggested to investigate the possibility of NSC. Pericolonic stranding, perfusion defect and dense mucosa were the most sensitive CT measures for NSC, detecting about 80%, 70%, and 62.5% of the cases, respectively. Awareness of NSC and familiarity with these CT signs enables us to make a differential diagnosis between this fatal condition and benign stool impaction.

In clinical practice, fecaloma-related necrotic stercoral colitis (NSC) is an infrequently and easily overlooked disease. It frequently occurs in patients who are elderly or have inactive status. High mortality is encountered when perforation takes place.

In fact, most fecal impaction is usually relieved by non-invasive management, meaning that surgical and pathologic evidence for NSC has been unobtainable. In this era of liberal computed tomography (CT) use for patients with acute abdomen in emergency departments, few articles about CT of stercoral colitis have been published.

Over the last few years, the authors have collected ten patients with clinical, surgical, pathologic and radiographic evidence of NSC. In practice, clinical clues alone are insufficient to exclude the disease. Characteristic CT presentations are useful to delineate this colon pathology, especially dense mucosa, pericolonic stranding, perfusion defect, and mucosal sloughing of colon.

The paper is an interesting one, but it needs major language refinement and some additional information to be provided. I then would suggest acceptation for publication, provided satisfactory revision requirements are met.

Peer reviewer: Dr. Giuseppe Chiarioni, Gastroenterological Rehabilitation Division of the University of Verona, Valeggio sul Mincio Hospital, Azienda Ospedale di Valeggio s/M, Valeggio s/M 37067, Italy

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Zheng XM

| 2. | Heffernan C, Pachter HL, Megibow AJ, Macari M. Stercoral colitis leading to fatal peritonitis: CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:1189-1193. |

| 3. | Rozenblit AM, Cohen-Schwartz D, Wolf EL, Foxx MJ, Brenner S. Case reports. Stercoral perforation of the sigmoid colon: computed tomography findings. Clin Radiol. 2000;55:727-729. |

| 4. | Hsiao TF, Chou YH. Stercoral perforation of colon: a rare but important mimicker of acute appendicitis. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:112.e1-112.e2. |

| 5. | Maurer CA, Renzulli P, Mazzucchelli L, Egger B, Seiler CA, Büchler MW. Use of accurate diagnostic criteria may increase incidence of stercoral perforation of the colon. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:991-998. |

| 6. | Chen JH, Shen WC. Rectal carcinoma with stercoral ulcer perforation. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:1018-1019. |

| 8. | Guyton DP, Evans D, Schreiber H. Stercoral perforation of the colon. Concepts of operative management. Am Surg. 1985;51:520-522. |

| 9. | Saegesser F, Sandblom P. Ischemic lesions of the distended colon: a complication of obstructive colorectal cancer. Am J Surg. 1975;129:309-315. |

| 10. | Boley SJ, Agrawal GP, Warren AR, Veith FJ, Levowitz BS, Treiber W, Dougherty J, Schwartz SS, Gliedman ML. Pathophysiologic effects of bowel distention on intestinal blood flow. Am J Surg. 1969;117:228-234. |

| 11. | Huang WS, Wang CS, Hsieh CC, Lin PY, Chin CC, Wang JY. Management of patients with stercoral perforation of the sigmoid colon: report of five cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:500-503. |

| 12. | Chang HK, Min BS, Ko YT, Kim NK, Kim H, Kim H, Cho CH. Obstructive colitis proximal to obstructive colorectal carcinoma. Asian J Surg. 2009;32:26-32. |

| 13. | Frager DH, Baer JW. Role of CT in evaluating patients with small-bowel obstruction. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 1995;16:127-140. |

| 14. | Furukawa A, Kanasaki S, Kono N, Wakamiya M, Tanaka T, Takahashi M, Murata K. CT diagnosis of acute mesenteric ischemia from various causes. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:408-416. |