Published online May 21, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i19.2411

Revised: May 8, 2010

Accepted: May 15, 2010

Published online: May 21, 2011

AIM: To investigate stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) procedures as surgical techniques for obstructed defecation syndrome (ODS) by analyzing specimen evaluation, anorectal manometry, endoanal ultrasonography and clinical follow-up.

METHODS: From January to December 2007, we have treated 30 patients. Fifteen treated with double PPH-01 staplers and 15 treated using new CCS 30 contour. Resected specimen were measured with respect to average surface and volume. All patients have been evaluated at 24 mo with clinical examination, anorectal manometry and endoanal ultrasonography.

RESULTS: Average surface in the CCS 30 group was 54.5 cm2 statistically different when compared to the STARR group (36.92 cm2). The average volume in the CCS 30 group was 29.8 cc, while in the PPH-01 it was 23.8 cc and difference was statistically significant. The mean hospital stay in the CCS 30 group was 3.1 d, while in the PPH-01 group the median hospital stay was 3.4 d. As regards the long-term follow-up, an overall satisfactory rate of 83.3% (25/30) was achieved. Endoanal ultrasonography performed 1 year following surgery was considered normal in both of the studied groups. Mean resting pressure was higher than the preoperative value (67.2 mmHg in the STARR group and 65.7 mmHg in the CCS30 group vs 54.7 mmHg and 55.3 mmHg, respectively). Resting and squeezing pressures were lower in those patients not satisfied, but data are not statistically significant.

CONCLUSION: The STARR procedure with two PPH-01 is a safe surgical procedure to correct ODS. The new Contour CCS 30 could help to increase the amount of the resected tissue without differences in early complications, post-operative pain and in hospital stay compared to the STARR with two PPH-01 technique.

- Citation: Naldini G, Cerullo G, Menconi C, Martellucci J, Orlandi S, Romano N, Rossi M. Resected specimen evaluation, anorectal manometry, endoanal ultrasonography and clinical follow-up after STARR procedures. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(19): 2411-2416

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i19/2411.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i19.2411

The prevalence of constipation in adults ranges from 2% to 27% in North America, particularly over 65 years old and with a female predominance[1]. There are two major types of constipation: secondary constipation and primary functional constipation, which can be divided into slow transit constipation, constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome, and obstructed defecation. Approximately half of constipated patients suffer from obstructed defecation[1]. Obstructed defecation syndrome (ODS) is characterized by a cohort of symptoms including incomplete evacuation with painful effort, unsuccessful attempts with long period spent in bathroom, bleeding after defecation, use of perineal support and/or odd posture. ODS can also depend on intussusception of the rectal wall, extending into the anal canal, usually defined as internal prolapse. This condition is even frequently associated with rectocele[2]. Many different surgical techniques have been described in literature to correct ODS with important limitations and different patterns of post-operative complications[3]. The stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) procedure is a surgical technique introduced to treat ODS due to rectocele and rectal intussusceptions and it has been demonstrated to be safe and effective[4,5]. Recently, a new device for the STARR procedure called the Curved Cutter Stapler 30 mm (CCS30) was developed by ETHICON ENDO-SURGERY Inc.® to correct ODS. The theoretical advantages of CCS30 include the ability to resect a single larger specimen and that it is more symmetrical than the other technique, with the avoidance of lateral “dog-ears”.

The purpose of our study was to compare the specimen features (average volume and surface) obtained using the traditional two staplers technique (STARR) with Contour CCS 30 (Transtar), and to evaluate the early and late postoperative outcome. Moreover, we evaluated if a different resection (larger and more symmetric) may be associated with a higher complication rate or with differences in clinical, manometric and sonographic results at the 24 mo follow-up.

From January to December 2007, 30 patients (all female; mean age 46.4 years old) suffering from ODS were treated in our department, 15 with double PPH-01 stapler and 15 with Contour CCS 30. All patients underwent a preoperative assessment mainly based on clinical evaluation, proctoscopy, defecography, anorectal manometry, and endoanal ultrasonography. A particular effort was made to investigate patient’s obstetric and gynaecologist history, as well as previous anal or abdominal surgery. A colonoscopy was performed when malignant or inflammatory disease was suspected. Longo OD and Wexner scores were preoperatively filled in with all patients.

Patients selected for surgery were those with: (1) failure of medical therapy (1.5 L/d of water, low-fiber diet, lactulose 10 g/d) with persistence of at least three of the following symptoms: feeling of incomplete evacuation, painful effort, unsuccessful attempts with long periods spent in bathroom, defecation with use of perineal support and/or odd posture, digital assistance, evacuation obtained only with use of enemas; and (2) at least two of the following findings at defecography: rectoanal intussusception extending 10 mm into the anal canal, rectocele deeper than 3 cm on straining or entrapping barium contrast after defecation. The presence of hemorrhoids was not a contraindication to the operation[3].

Patients with non-relaxing puborectalis muscle at defecography, with synchronous genital prolapse, or cystocele requiring associated transvaginal operations, fecal incontinence, mental disorders, or general contraindications to surgery were excluded[3]. Patients with pelvic floor dyssynergia confirmed by clinical and instrumental evaluation were treated with pelvic floor training.

All patients gave informed, written consent. In the first phase, patients were operated on with STARR procedure (double PPH-01) while Contour Transtar was used as incoming technique in a second instance so that a total of 30 patients were enrolled in the present study, equally distributed according to the two techniques described (15 STARR with double PPH-01 and 15 Transtar with CCS 30). All surgical procedures were carried out in the lithotomy position by a single senior surgeon (GN). Preoperative enema and antibiotic prophylaxis with intravenous Metronidazole 500 mg were performed.

Spinal or general anaesthesia were both carried out and a particular effort was made to the muscle curarization in order to avoid, with a constant muscular relaxation, a sudden sphincter stretching during surgery.

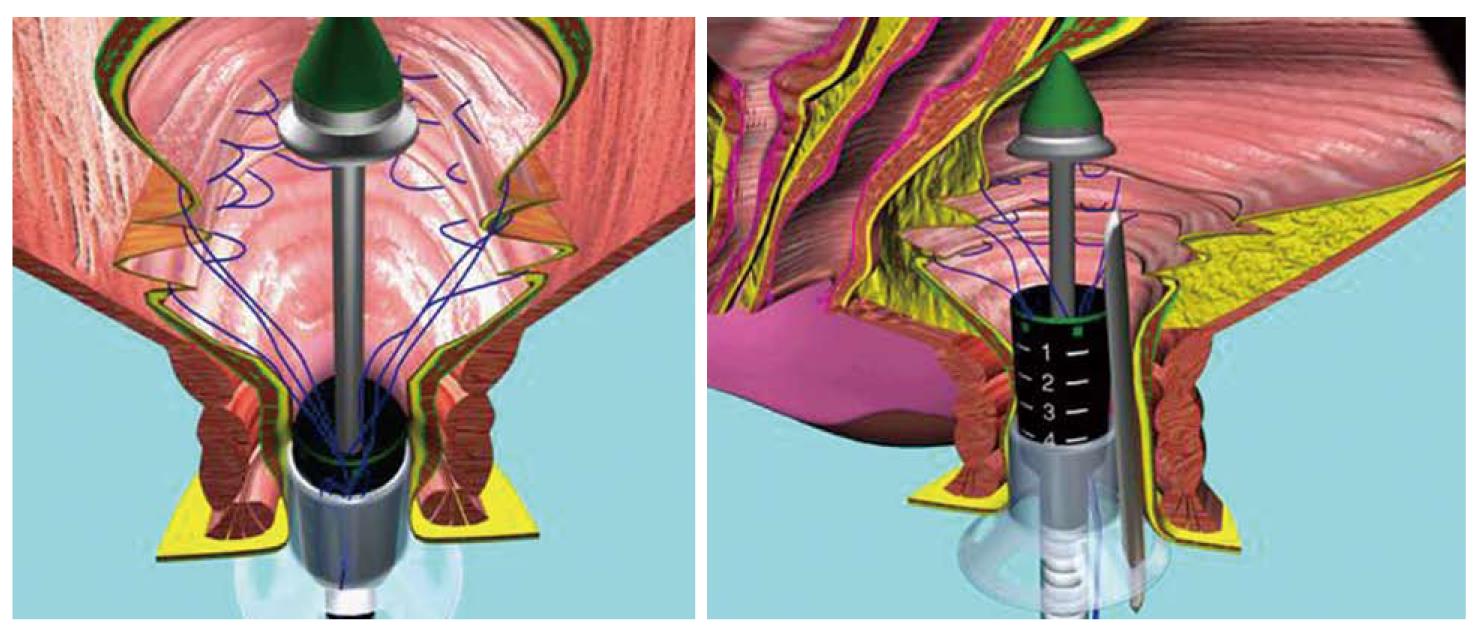

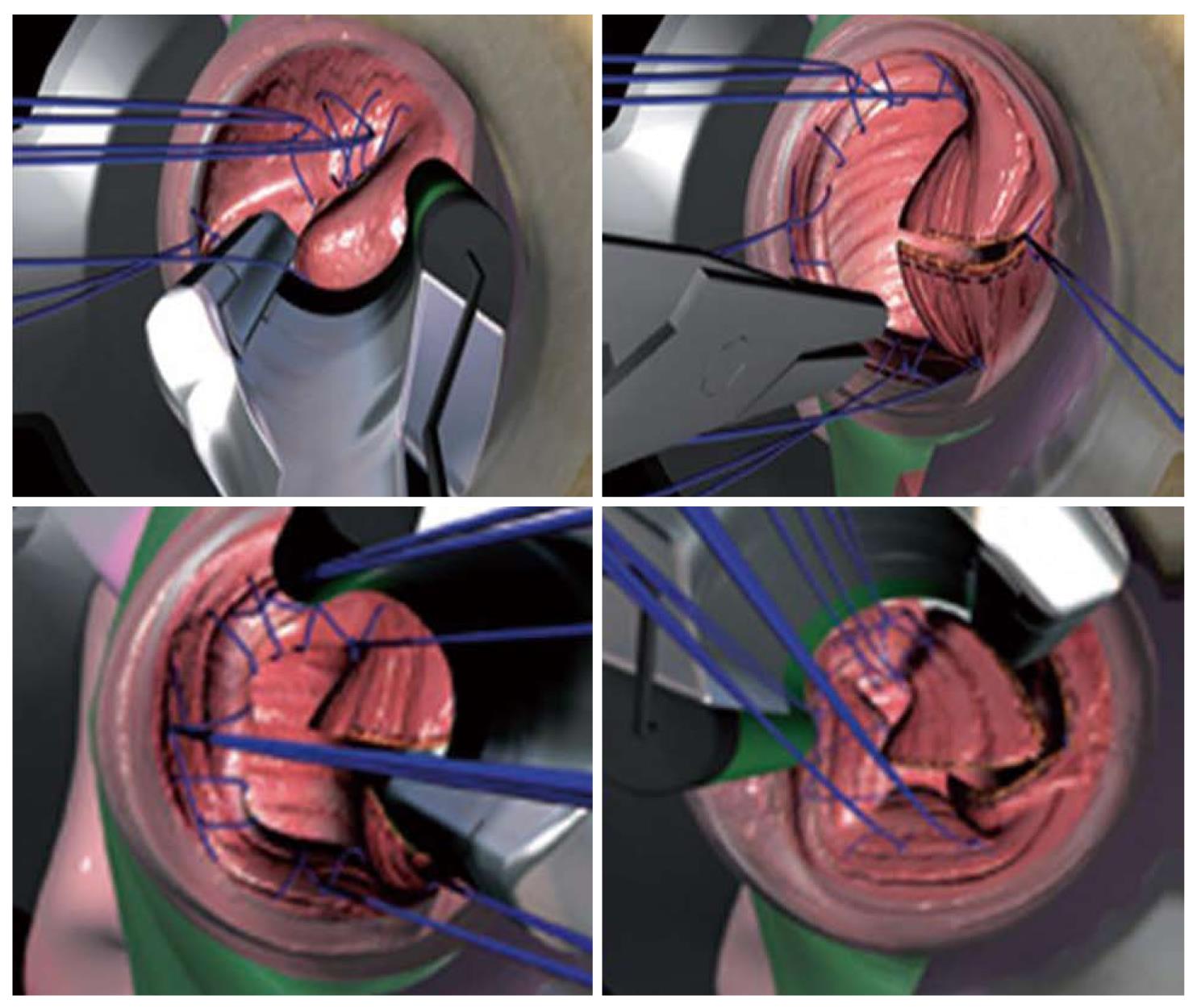

PPH-STARR was performed using two PPH 01-stapling devices (ETHICON Endosurgery, Cincinnatti, USA) as described elsewhere[3]. In addition, 2/0 vicryl sutures were used to oversew the staple line in order to reduce postoperative bleeding (Figure 1). For the Contour Transtar-procedure, a CCS-30 stapler kit (ETHICON Endosurgery, Cincinnati, USA) was used. Briefly, the procedure starts with gentle dilatation of the anus and insertion of the circular anal dilator (CAD), which is then fixed to the perineum with 4 sutures. The internal prolapse is verified by insertion and withdrawal of a gauze swab. Starting at the 2 o’clock position, a 2/0 Vicryl traction suture is placed at the apex of the prolapse. A further 4 traction sutures are then placed around the circumference of the prolapse. A final suture to mark the site and depth of the first stapler firing is placed at the 3 o’clock position. The Contour Transtar device is introduced into the rectum and the prolapse at the 3 o’clock position and pulled into the jaws using the previously placed traction suture and marking suture. The stapler is closed and, after checking the vagina for inadvertent incorporation of the vaginal mucosa, the first stapler firing is performed to produce a radial cut into the prolapse. After changing the stapler cartridge, the device is re-introduced into the rectum and sequential circumferential resection of the prolapse is performed using 4 to 5 separate stapler firings to complete the resection. In order to secure haemostasis, single 2/0 vicryl stitches were used to under-run the staple line. Finally an easy-flow-drainage is placed in the anus as an indicator of bleeding (Figure 2).

With concern to the specimen, it was opened and extended so that surface and volume could be measured. The volume was measured using a controlled volume jar and obtained by variations in the volume of the jar.

Patients were treated with a standard protocol for pain control with intramuscular Ketorolac 30 mg and intravenous paracetamol 10 mg as a rescue dose. The post operative pain was evaluated with the Visual Analogical Scale (VAS) at the first and second day after the surgical procedure (twice a day).

All patients were prospectively evaluated after 7 d and 1 mo from the discharge. As regards long term follow-up, patients were asked to be clinically evaluated at 12 mo following surgery and all agreed. Moreover, they were all contacted and evaluated again 24 mo after surgery. Clinical examination and Longo OD/Wexner questionnaires were achieved as well as endoanal ultrasonography (Bruel and Kjaer 10 MHz 3-D rotating probe) and anorectal manometry.

All variables including demographic, clinical, operative and manometric findings were recorded and statistically analysed. Analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, SPSS 17.0 for Windows, XP, SPSS Inc., Chicago IL. Log-rank test was used to assess the difference between the groups. A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

The two groups under study (15 patients operated on with double PPH-01 and 15 patients with CCS 30) were homogeneous with respect to the demographic (mean age) and clinical data (obstetric/gynaecologist and general history; clinical examination). With regards to the resected specimen, average surface in the CCS 30 group was 54.5 cm2 statistically different when compared to the STARR group (36.92 cm2). The average volume in the CCS 30 group was 29.8 cc, while in the PPH-01 it was 23.8 cc and difference was statistically significant as well (Table 1). With concern to post-operative pain during the first and second postoperative day, we found that in the CCS 30 group the VAS was 1.3 (range 0-4) and 1.1 (range 0-3) respectively, while in the group treated with two PPH-01 technique (STARR) the VAS was 2.55 (range 0-4) and 0.95 (range 0-3, 5). One month following surgery patients did not complain of pain anymore. The mean hospital stay was 3.1 d (range 2-5 d) in the CCS 30 group and 3.4 d (range 3-6 d) in the PPH-01 group (Table 1).

Only one complication, acute bleeding, occurred in the CCS 30 group (3.3%), promptly treated with surgery in order to control the bleeding. We have not recorded other perioperative complications such as rectal abscess, post-operative hematomas, tenesmus, or rectal strictures.

As regards the long-term follow-up, endoanal ultrasonography performed 1 year following surgery was considered normal in both of the studied groups. Above all, neither major damage nor sonographically demonstrable sphincter fragmentations were noticed in the endoanal exam performed at the follow-up. Urgency was complained by 5 patients (3 in the double PPH group and 2 in the Transtar one) and incontinence by 3 patients (2 in the double PPH group and 1 in the Transtar one), both resolved in some measure during the follow-up period with an overall satisfactory rate of 83.3% (25/30). In the study groups, the postoperative Longo and Wexner scores for ODS showed an improvement that was statistically significant with respect to the preoperative value.

Findings of anorectal manometry at the 1 year follow-up are showed in Table 2. In both groups of patients, the mean resting pressure is higher than the preoperative value (67.2 mmHg in the STARR group and 65.7 mmHg in the CCS30 group vs 54.7 mmHg and 55.3 mmHg respectively). Resting and squeezing pressures are lower in those patients not satisfied, but data are not statistically significant. Even if data are not statistically significant, postoperative rectal compliance seems to be lower in the STARR group than in the CCS group (Table 2).

Treatment of ODS is a widely debate topic, and the first consideration concerning the right indications of surgical procedure is to correct the ODS[6,7]. Defecography shows a rectocele or rectal intussusception in 81 and 35 percent of asymptomatic female respectively[8], therefore the presence of the rectocele and rectal intussusception are not an indication for surgery. In fact, only symptomatic patients with rectocele and rectal intussusception are suitable for a surgical treatment. For this reason, and according to the literature, we recommend a strict and careful selection of patients[3]. Moreover, we also believe that patients with pelvic floor dyssynergia, clearly demonstrated by clinical and instrumental evaluation, represent a particular population so that pelvic floor training should be considered the main therapeutic choice with respect to surgery.

The STARR procedure with two PPH-01 is a safe, well tolerated surgical procedure effectively restoring the anatomy and the function of the anorectum in patients with ODS due to rectocele and rectal intussusception, with a low rate of complication and a short hospital stay[9,10]. In the literature it is not clearly established which surgical technique is the most effective for the treatment of ODS[3]. In fact, no randomized trial has yet clearly demonstrated the best approach[3]. Moreover, in the era of healthcare cost management, it could be useful to underline that official prices of double PPH-01 and CCS 30 techniques are €800 and €1, 789 respectively. The new CCS 30 Contour has the advantage of a new semicircular head allowing the resection under direct vision into the anal canal. Moreover, it allows a more regulated specimen than using two PPH-01 and our data confirm this assessment in agreement with the international literature, as the amount of rectal resection can be easily regulated with regards to the depth of the rectal intussusception. Analyzing our data, we found a statistically significant difference in surface and volume between the two PPH-01 and CCS 30 Contour specimens. In accordance to the concept of a more regulated resection with CCS 30, the average surface and volume have turned out greater in the STARR group with this new device. Therefore, STARR with the CCS 30 Contour is a procedure that allows removal of a larger, more regular and more symmetrical specimen and, as a consequence, in a perfect cylinder compared with the 2 irregular specimens obtained by STARR with two PPH-01.

This data could provide an explanation for the reduced rectal compliance in the STARR group compared to the CCS30 group. In fact, the resection performed with the double PPH technique could result in an hourglass shape of the rectum, with a stricture at staple line level. On the contrary, the resection obtained with CCS30, performed with four or more firings, could results in a larger and softer staple line.

Although in the literature correlations between the amount of the prolapse removed and the functional improvement as well as between the functional failure and the insufficient removal of the prolapsed have not been demonstrated yet, we believe that Contour CCS 30 might increase the functional results of the STARR procedure even if our data and the short follow-up cannot support this theory yet.

Analyzing our data there are not significant differences between the CCS 30 Contour and the STARR with two PPH-01 groups concerning the hospital stay, postoperative VAS evaluation and, above all, we have not recorded any differences between the two groups concerning major early complications[11]. The literature reports 5% of post-operative bleeding following STARR with two PPH-01[6]. Although the average surface and volume of the resected specimen in STARR with CCS 30 group were larger compared to STARR with double PPH-01 group, in our experience complication rate is not increased. Actually the literature reports only one case of acute complications after STARR with CCS 30 contour; retroperitoneal and mediastinal emphysema treated with medical therapy[12].

In our study, incidences of fecal incontinence and urgency in both groups confirm the results of the international literature, but no significant alteration was found with regards to endoanal ultrasonography and anorectal manometry performed at the follow-up. In a recent study Renzi et al[13] report 2.9% of post-operative bleeding after STARR with CCS30 contour and our data confirmed these rates. Most authors report incontinence to flatus (IF) and urge to defecate (UD) that tends to resolve in few weeks[2]. Arroyo in a recent series of 104 patients, treated for ODS with a double PPH-01 STARR, reports an incidence of IF and UD at 1 mo of 22.1% and 26.9%, respectively[6]. In a published series of 90 patients, Boccasanta reports an IF incidence of 8.9% and 17.8% of UD 1 mo following surgery[2].

Some authors[3] tried to explain the incontinence advocating a sphincter or mucosal injury or an excessive anal dilation, but our findings with postoperative endoanal ultrasonography did not show any sphincter damage following surgery. According to Pechlivanides, IF and UD could be due to rectal wall edema and reduced rectal compliance[9]. Actually, in our experience, anorectal manometry at 1 year following surgery revealed a decreased rectal compliance, particularly in the STARR group with two PPH. On the other hand, an increased resting pressure is a common finding in these patients and might be a consequence of the lower rectal compliance as a compensatory mechanism. Our results are based on a short outcome and a small non-randomized population, so these theories should be further investigated on the basis of a longer follow-up.

In conclusion, in our experience STARR with Contour CCS 30 is a safe and feasible technique allowing the excision of a major amount of tissue without any increasing of the early complication rate or sphincter injuries, as demonstrated by the endoanal ultrasonography. Moreover, resected tissue after a Contour CCS 30 procedure is clearly more symmetric and larger in dimension, without any difference in post-operative pain and hospital stay compared to the STARR with two PPH-01 technique. On the other hand, in the current literature[14] a correlation between the amount of the prolapse removed and the functional improvement in patients with ODS has not been reported yet and so far it has not been demonstrated to have any correlation between functional failure and insufficient removal of the prolapse. Further studies should investigate longer clinical outcomes and allow us to evaluate if a larger rectal resection results in a functional improvement emphasizing the real advantages of CCS 30 with respect to STARR.

Obstructed defecation syndrome is a common disease, particularly in the female population, treated with two different stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) procedures.

Both STARR procedures are worldwide performed. All specimen data, manometric and sonographic evaluation should be considered with a clinical follow-up as well in the evaluation of these surgical procedures.

The authors ought to be congratulated for a very well conducted study and for the large series of STARR procedures performed.

Peer reviewer: Alessandro Fichera, MD, FACS, FASCRS, Assistant Professor, Department of Surgery - University of Chicago, 5841 S. Maryland Ave, MC 5031, Chicago, IL 60637, United States

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Rutherford A E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Khaikin M, Wexner SD. Treatment strategies in obstructed defecation and fecal incontinence. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3168-3173. |

| 2. | Arroyo A, Pérez-Vicente F, Serrano P, Sánchez A, Miranda E, Navarro JM, Candela F, Calpena R. Evaluation of the stapled transanal rectal resection technique with two staplers in the treatment of obstructive defecation syndrome. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:56-63. |

| 3. | Boccasanta P, Venturi M, Stuto A, Bottini C, Caviglia A, Carriero A, Mascagni D, Mauri R, Sofo L, Landolfi V. Stapled transanal rectal resection for outlet obstruction: a prospective, multicenter trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1285-1296; discussion 1296-1297. |

| 4. | Longo A. Obstructed defecation because of rectal pathologies. Novel surgical treatment: stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR). In: Acts of 14th international colorectal disease symposium. Fort Lauderdale, FL 2003; . |

| 5. | Lehur PA, Stuto A, Fantoli M, Villani RD, Queralto M, Lazorthes F, Hershman M, Carriero A, Pigot F, Meurette G. Outcomes of stapled transanal rectal resection vs. biofeedback for the treatment of outlet obstruction associated with rectal intussusception and rectocele: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1611-1618. |

| 6. | Arroyo A, González-Argenté FX, García-Domingo M, Espin-Basany E, De-la-Portilla F, Pérez-Vicente F, Calpena R. Prospective multicentre clinical trial of stapled transanal rectal resection for obstructive defaecation syndrome. Br J Surg. 2008;95:1521-1527. |

| 7. | Stapled haemorrhoidopexy for the treatment of haemorrhoids. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2007. . |

| 8. | Gagliardi G, Pescatori M, Altomare DF, Binda GA, Bottini C, Dodi G, Filingeri V, Milito G, Rinaldi M, Romano G. Results, outcome predictors, and complications after stapled transanal rectal resection for obstructed defecation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:186-195; discussion 195. |

| 9. | Pechlivanides G, Tsiaoussis J, Athanasakis E, Zervakis N, Gouvas N, Zacharioudakis G, Xynos E. Stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) to reverse the anatomic disorders of pelvic floor dyssynergia. World J Surg. 2007;31:1329-1335. |

| 10. | Corman ML, Carriero A, Hager T, Herold A, Jayne DG, Lehur PA, Lomanto D, Longo A, Mellgren AF, Nicholls J. Consensus conference on the stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) for disordered defaecation. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8:98-101. |

| 11. | Naldini G. Serious unconventional complications of surgery with stapler for haemorrhoidal prolapse and obstructed defaecation because of rectocoele and rectal intussusception. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:323-327. |

| 12. | Schulte T, Bokelmann F, Jongen J, Peleikis HG, Fändrich F, Kahlke V. Mediastinal and retro-/intraperitoneal emphysema after stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR-operation) using the Contour Transtar stapler in obstructive defecation syndrome. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:1019-1020. |

| 13. | Renzi A, Talento P, Giardiello C, Angelone G, Izzo D, Di Sarno G. Stapled trans-anal rectal resection (STARR) by a new dedicated device for the surgical treatment of obstructed defaecation syndrome caused by rectal intussusception and rectocele: early results of a multicenter prospective study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:999-1005. |

| 14. | Isbert C, Reibetanz J, Jayne DG, Kim M, Germer CT, Boenicke L. Comparative study of Contour Transtar and STARR procedure for the treatment of obstructed defecation syndrome (ODS)--feasibility, morbidity and early functional results. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:901-908. |