Published online Apr 7, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i13.1766

Revised: November 17, 2010

Accepted: November 24, 2010

Published online: April 7, 2011

AIM: To evaluate the value of endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) in the choice of endoscopic therapy strategies for mesenchymal tumors of the upper gastrointestinal tract.

METHODS: From July 2004 to September 2010, 1050 patients with upper gastrointestinal mesenchymal tumors (GIMTs) were diagnosed using EUS. Among them, 201 patients underwent different endoscopic therapies based on the deriving layers, growth patterns and lesion sizes.

RESULTS: Using EUS, we found 543 leiomyomas and 507 stromal tumors. One hundred and thirty-three leiomyomas and 24 stromal tumors were treated by snare electrosection, 6 leiomyomas and 20 stromal tumors were treated by endoloop, 10 stromal tumors were treated by endoscopic mucosal resection and 8 stromal tumors were treated by endoscopic submucosal dissection. Complete resection of the lesion was achieved in all cases. Of the mesenchymal tumors, 90.38% diagnosed by EUS were also identified by pathohistology. All wounds were closed up nicely and no recurrence was found in the follow-up after 2 mo.

CONCLUSION: EUS is an effective means of diagnosis for upper GIMTs and is an important tool in choosing the endoscopic therapy for GIMTs, by which the lesions can be treated safely and effectively.

- Citation: Zhou XX, Ji F, Xu L, Li L, Chen YP, Lu JJ, Wang CW, Huang W. EUS for choosing best endoscopic treatment of mesenchymal tumors of upper gastrointestinal tract. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(13): 1766-1771

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i13/1766.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i13.1766

Gastrointestinal mesenchymal tumors (GIMTs) originate from mesenchymal cells other than epithelial cells or lymphocytes. They are further classified as stromal tumors, leiomyomas, leiomyosarcomas, neural tumors, fibroblast tumors or liparomphalus. Clinically, mesenchymal tumors are usually incidentally discovered as subepithelial bulges during routine endoscopic examinations for unrelated conditions. The classification and management of these lesions can be challenging. In recent years, with the wide use of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) to clarify the nature and origin of the subepithelial tumor, great progress has been made in diagnosis and treatment of GIMTs[1,2]. Importantly, under the guidance of the EUS, GIMTs can be removed by appropriate endoscopic treatment without severe complications[2-4].

From July 2004 to September 2010, we analyzed 1050 patients with GIMTs diagnosed by EUS in our hospital. Of these patients, 201 underwent different endoscopic therapies based on the EUS results. Our aim in this retrospective study was to evaluate the value of EUS in the choice of endoscopic therapy strategies for mesenchymal tumors of the upper gastrointestinal tract.

The medical records of 1050 patients with upper GIMTs diagnosed by EUS examination in the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University were retrospectively reviewed. All these patients with submucosal protruding lesions in the upper gastrointestinal tract by routine endoscopy were examined by EUS. There were 499 men and 551 women, with a mean age of 52.6 years (range, 19-86 years). Of these patients, 201 patients underwent endoscopic therapy in the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University, Beilun Zongrui Hospital, the Traditional Chinese Medical Hospital of Ninghai and Jinhua Wenrong Hospital, respectively.

A two-channel endoscope (GIF-2T240, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and a 12 MHz probe (GF-UM 2R, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) were used for the ultrasonographic study. Scanning of the tumor was performed after filling the upper gastrointestinal tract with 100-500 mL of deaerated water. Diagnosis was made according to the layer of origin, size, nature, internal echo pattern, outer margin and grow pattern of the lesion. Following the EUS procedure, if the lesion was identified as an intramural lesion ≤ 2.5cm, endoscopic treatment was performed. A lesion > 2.5 cm in size and suspected to be malignant was suggested for surgery. A large proportion of patients were followed up with EUS, because their poor conditions were unsuited for the therapy or the lesion was too small.

An Olympus GIF-XQ240/260 gastroscope (Tokyo, Japan) was used for the resection when it was indicated. Informed consent was given by each patient before the endoscopic therapy. Four different resection techniques were used: snare electrosection, endoloop, endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD).

EMR procedure: Epinephrine (0.001%) was injected into the submucosal layer to lift the lesion, and then a conventional electrosurgical snare (FD-IU, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and an electrosurgical unit (VIO 200D, ERBE, Tubingen, Germany) were used for removal of the overlying mucosa and resection of the tumor.

ESD procedure: the surrounding area of the lesion was marked with argon plasma coagulation (APC 300A, ERBE, Tubingen, Germany). Normal saline solution with 0.002% indigo carmine and 0.001% epinephrine was injected into the submucosal layer to lift the lesion. An initial incision was made outside the marking dots with a hook-knife (KD-620LR, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The submucosal resection under the lesion was done with insulation-tipped (IT) electrosurgical knife (KD-610L, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Finally, a snare was used to remove the surrounding tissues. Bleeding and visible vessels in the resection area were closed using hemoclips (HX-201YR-135, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Postoperative EUS examination was made to check whether the lesions were completely removed except those with endoloop ligation. The specimens were sent for pathologic study, some of which were assayed by immunohistochemistry. All 201 patients were examined two months later with EUS.

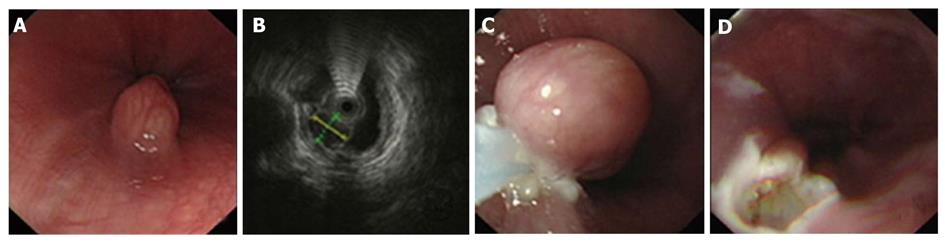

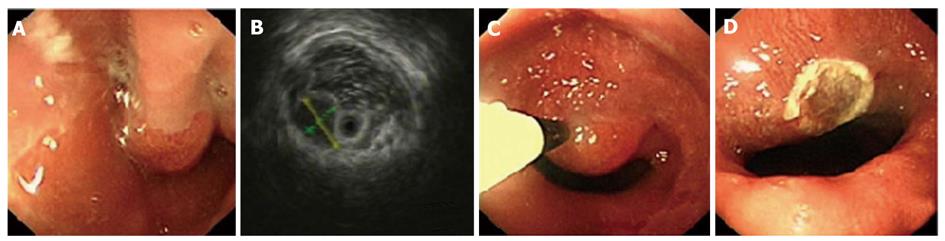

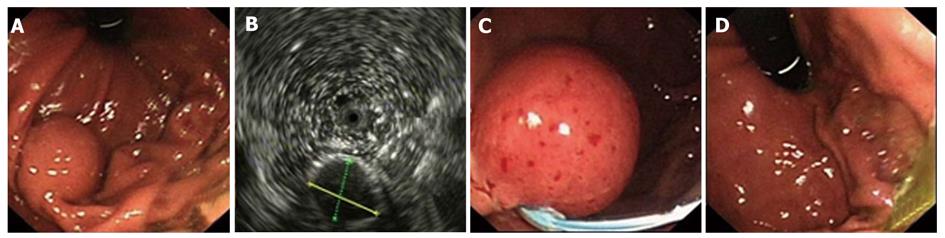

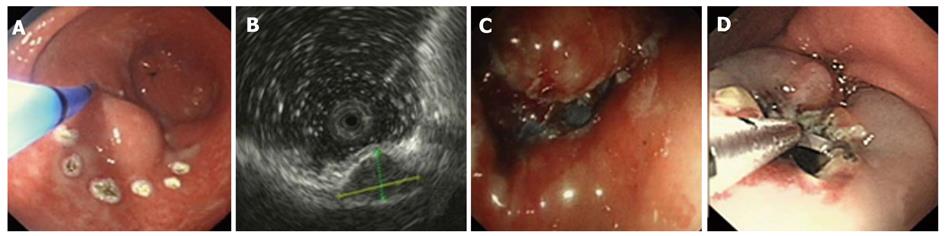

Using EUS, we identified 1050 patients with GIMTs, 543 of them had leiomyomas. Five hundred and twenty lesions were in the esophagus, 22 in the stomach, and 1 in the duodenum. The mean maximal tumor diameter was 3.3 cm. Five hundred and seven cases were stromal tumors. Forty-nine lesions were in the esophagus, 428 were in the stomach, and 30 were in the duodenum. The mean maximal tumor diameter was 6.6 cm. EUS features of leiomyomas and stromal tumors were characteristic with regular borders, a hypoechoic mass with homogeneous or heterogeneous echo patterns (Figures 1, 2, 3, 4). The echogenicity of leiomyomas was slightly lower than the normal proper muscle layer, while that of stromal tumors was slightly higher. Malignant stromal tumors often appeared as a heterogeneous mass with irregular borders.

One hundred and thirty-nine leiomyomas and 62 stromal tumors underwent endoscopic therapy after EUS examination. No obvious malignant signs were seen in these lesions. The location, origin level and removal methods of the lesions are shown in Table 1. The mean maximal tumor diameter was 2.5 cm. For a tumor protruding into the cavity, if it originated from the muscularis mucosa or from submucosa ≤ 1 cm, snare electrosection was directly used. If the lesion originating from submucosa was flat and > 1cm, electrosection would be expected to fail, and other treatments, such as endoloop, EMR or ESD, were used. For a lesion originating from muscularis propria but not growing outward, endoloop or ESD was used. Among these patients, 133 leiomyomas and 24 stromal tumors were treated by snare electrosection, 6 leiomyomas and 20 stromal tumors were treated by endoloop, 10 stromal tumors were treated by EMR and 8 stromal tumors were treated by ESD (Figures 1-4). Complete resection of the lesion was achieved in all cases. No residual lesion was detected by postoperative EUS examination except for those by endoloop ligation. None of the patients suffered from severe hemorrhage or resection-related perforation. Postoperative histological results showed that 141 of 156 patients were in agreement with the preoperative diagnosis of EUS. All the specimens tested had complete envelope and negative resection margin in pathology. Wounds were closed up nicely in all patients when rechecked after two months. No residual lesion was detected by EUS examination and pathology demonstrated negative results at the same time.

| Diagnosis by EUS | Location | Layer of origin | Treatment | ||||||

| Esophagus | Stomach | Muscularis mucosa | Submucosa | Muscularis propria | Snare electrosection | Endoloop | EMR | ESD | |

| Leiomyoma | 134 | 5 | 121 | 15 | 3 | 133 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Stromal tumor | 22 | 40 | 18 | 19 | 25 | 24 | 20 | 10 | 8 |

| Total | 156 | 45 | 139 | 34 | 28 | 157 | 26 | 10 | 8 |

Leiomyomas and stromal tumors are the most common GIMTs of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Many lesions are subepithelial, and they are often difficult to diagnose by general endoscopy. Some also need to be identified with extrinsic compression. EUS can reliably characterize the nature, size, and layer of origin of lesions, and accurately differentiate intramural from extramural, leading to a diagnosis[5]. Features of leiomyomas and stromal tumors seen with EUS often include: a round shape, and a homogeneous, hypoechoic mass with regular borders[6]. A marginal halo, hyperechogenic spots and higher echogenicity as compared with the normal muscle layer is seen more frequently in stromal tumors than in the leiomyomas[7]. Malignant stromal tumors are characterized by large size (> 5 cm), irregular borders, and echogenic foci[8,9].

In this study, we identified 1050 patients with GIMTs using EUS. There were 543 leiomyomas and 507 stromal tumors. The majority of leiomyomas were located in the esophagus while most stromal tumors were located in the stomach, which is in accordance with other studies[6-10]. For these mesenchymal tumors, 90.38% diagnosed by EUS were also identified by pathohistology. Among these, 5 retention cysts, 4 stromal tumors with leiomyoma differentiation, and 1 hyperplastic polyp were diagnosed as leiomyoma, and 3 leiomyoma and 2 hyperplastic polyps were diagnosed as stromal tumors by EUS. Submucosal retention cysts are small and often filled with thick fluid, and thus the ultrasonophic image is of a hypoechoic mass that may be confused with mesenchymal tumors. Stromal tumors with leiomyoma differentiation are also difficult to discriminate by routine pathology and should be identified by immunohistochemistry. Samples from EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsies can be sent for cytological, pathological and immunohistochemical assays which may enable clinicians to make more accurate diagnoses than using EUS examination alone[6-11].

In the past, conventional endoscopy could not accurately determine the location and categorization of subepithelial lesions. Therefore, GIMTs were usually treated by surgery. The introduction of EUS has solved these problems and it has played an important role in the choice of endoscopic therapy for mesenchymal tumors. Based on EUS images, we treated 201 GIMTs with different endoscopic therapies, including snare electrosection, endoloop, EMR and ESD. Complete resection of the lesions was achieved in all cases. None of the patients suffered from severe hemorrhage or resection-related perforation. All wounds were closed up nicely and no recurrence was found in the follow-up after 2 mo.

Electrosection is the most common endoscopic treatment, and its value for the treatment of gastrointestinal submucosal tumors has been recognized[12,13]. It is mainly used for protuberant lesions (especially the pedunculated ones). In this study, 157 GIMTs arising from non-muscularis propria, with a diameter of ≤ 1cm, were treated by snare electrosection after EUS examination. It is reported that serious complications rarely occurred when electrosection is used to cut non-muscularis propria tumors with a diameter ≤ 3 cm[3]. Tumors originating from muscularis propria are associated with an increased risk of perforation and hemorrhage complications during endoscopic treatment, and snare electrosection was not used in these cases.

Compared with ordinary snare removal, EMR is more suitable for the treatment of flat lesions generally confined to < 2 cm[14]. In this study, 10 flat lesions were treated by EMR. We injected 0.001% epinephrine into the submucosal layer to lift the lesion and made it easy to snare. Furthermore, this may provide a buffer to protect the inherent muscle function, which could reduce the bleeding and perforation risk during the process of muscle removal. Examination by EUS before surgery to determine the size and depth of lesions could help determine the injection site and the resection scope.

Endoloop ligation of tumors at the base, blocking blood supply and causing tumor necrosis, could significantly reduce the risk of hemorrhage and perforation[15,16]. But, the procedure is not suitable for large lesions. Incomplete ligation might leave residual tumors, while ligation could increase the risk of hemorrhage and perforation. Therefore, the range and depth of ligation should be strictly controlled according to the results of EUS during surgery. In the past, the majority of tumors studied have been only the muscularis mucosa and submucosa[3]. Recently, it was reported that endoloop could remove tumors arising from muscularis propria safely and effectively[15,17]. In this study, we also used endoloop removal of lesions arising from muscularis propria, without hemorrhage or perforation. The tumor from the muscularis propria can grow inside or outside the cavity, therefore, preoperative EUS for defining the tumor growth pattern is very important to determine whether the lesion can be safely and completely removed.

ESD should be performed using a high-frequency electric knife to dissect the subepithelial tumor, which is more suitable for treatment of large and flat lesions. Tumors derived from the muscularis mucosa and submucosa can be completely dissected[18,19]. It is difficult to dissect lesions from the muscularis propria because of the increased risk of hemorrhage and perforation. In Lee et al ’s[20] study, among 12 cases of gastrointestinal submucosal muscle tumors arising from muscularis propria treated by ESD, 9 tumors were completely dissected. The size of these tumors ranged from 0.6 to 4 cm (average, 2 cm). In this study, 8 stromal tumors arising from submucosa or muscularis propria were treated safely by ESD. All of them were dissected once and clipping was used to close deep wounds to reduce hemorrhage and perforation risk.

Our clinical practice demonstrates that endoscopic treatment can be applied to GIMTs arising from muscularis mucosa, submucosa and muscularis propria. Based on the results of the EUS procedure, lesions > 2.5 cm in size and suspected to be malignant should be considered for surgery. Moreover, if the tumor grew outside the cavity, endoscopic treatment should be aborted as well. We also suggested a follow-up with EUS for the few patients who are not indicated for the endoscopic therapy or whose tumor is too small.

In conclusion, EUS can help determine the origin, size, shape, nature and growth pattern of lesions, with a high diagnostic accuracy for upper GIMTs. Preoperative EUS examination is important for choosing the type of endoscopic therapy for mesenchymal tumors, by which the lesions can be treated safely and effectively.

Clinically, gastrointestinal mesenchymal tumors (GIMTs) are usually incidentally discovered as subepithelial bulges during routine endoscopy for unrelated conditions. The classification and management of these lesions can be challenging.

With the wide use of endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) to clarify the nature and origin of the subepithelial tumor, great progress has been made in diagnosis and treatment of GIMTs. However, the value of EUS in the choice of endoscopic treatment strategies for GIMTs has not been well established.

This study indicated that EUS could help determine the origin, size, shape, nature and growth pattern of lesions, with a high diagnostic accuracy for upper GIMTs. Under the guidance of the EUS, GIMTs could be removed by appropriate endoscopic treatment, such as snare electrosection, endoloop, endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) without severe complications.

The results of this study demonstrate that EUS is an effective means of diagnosis for upper GIMTs. Preoperative EUS examination is important for choosing the type of endoscopic therapy for mesenchymal tumors. The study will guide the clinical application of EUS in the endoscopic therapy for upper GIMTs.

GIMTs are tumors which originate from mesenchymal cells other than epithelial cells or lymphocytes. They are further classified as stromal tumors, leiomyomas, leiomyosarcomas, neural tumors, fibroblast tumors or liparomphalus. EMR is a minimally invasive technique for resection of a lesion that requires the separation of the submucosa by injecting a fluid agent. ESD is a new endoscopic method using special knife for complete en bloc resection of early gastrointestinal neoplasms.

This is a well written paper which describes the experience of the authors in the EUS diagnosis and subsequent endoscopic treatment of gastrointestinal mesenchymal tumors. The pictures well support the authors’ findings and conclusions.

Peer reviewer: Massimo Raimondo, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic, 4500 San Pablo Road, Jacksonville, FL 32224, United States

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Oh YS, Early DS, Azar RR. Clinical applications of endoscopic ultrasound to oncology. Oncology. 2005;68:526-537. |

| 2. | Huang WH, Feng CL, Lai HC, Yu CJ, Chou JW, Peng CY, Yang MD, Chiang IP. Endoscopic ligation and resection for the treatment of small EUS-suspected gastric GI stromal tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1076-1081. |

| 3. | Martínez-Ares D, Lorenzo MJ, Souto-Ruzo J, Pérez JC, López JY, Belando RA, Vilas JD, Colell JM, Iglesias JL. Endoscopic resection of gastrointestinal submucosal tumors assisted by endoscopic ultrasonography. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:854-858. |

| 4. | Sun S, Ge N, Wang S, Liu X, Lü Q. EUS-assisted band ligation of small duodenal stromal tumors and follow-up by EUS. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:492-496. |

| 5. | Shim CS, Jung IS. Endoscopic removal of submucosal tumors: preprocedure diagnosis, technical options, and results. Endoscopy. 2005;37:646-654. |

| 6. | Ji F, Wang ZW, Wang LJ, Ning JW, Xu GQ. Clinicopathological characteristics of gastrointestinal mesenchymal tumors and diagnostic value of endoscopic ultrasonography. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:e318-e324. |

| 7. | Kim GH, Park do Y, Kim S, Kim DH, Kim DH, Choi CW, Heo J, Song GA. Is it possible to differentiate gastric GISTs from gastric leiomyomas by EUS? World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3376-3381. |

| 8. | Okubo K, Yamao K, Nakamura T, Tajika M, Sawaki A, Hara K, Kawai H, Yamamura Y, Mochizuki Y, Koshikawa T. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy for the diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the stomach. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:747-753. |

| 9. | Shah P, Gao F, Edmundowicz SA, Azar RR, Early DS. Predicting malignant potential of gastrointestinal stromal tumors using endoscopic ultrasound. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1265-1269. |

| 10. | Kang YN, Jung HR, Hwang I. Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical features of gastointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer Res Treat. 2010;42:135-143. |

| 11. | Scarpa M, Bertin M, Ruffolo C, Polese L, D’Amico DF, Angriman I. A systematic review on the clinical diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Surg Oncol. 2008;98:384-392. |

| 12. | Wehrmann T, Martchenko K, Nakamura M, Riphaus A, Stergiou N. Endoscopic resection of submucosal esophageal tumors: a prospective case series. Endoscopy. 2004;36:802-807. |

| 13. | Stergiou N, Riphaus A, Lange P, Menke D, Köckerling F, Wehrmann T. Endoscopic snare resection of large colonic polyps: how far can we go? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2003;18:131-135. |

| 14. | Li H, Lu P, Lu Y, Liu C, Xu H, Wang S, Chen J. Predictive factors of lymph node metastasis in undifferentiated early gastric cancers and application of endoscopic mucosal resection. Surg Oncol. 2010;19:221-226. |

| 15. | Sun S, Jin Y, Chang G, Wang C, Li X, Wang Z. Endoscopic band ligation without electrosurgery: a new technique for excision of small upper-GI leiomyoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:218-222. |

| 16. | Lee SH, Park JH, Park do H, Chung IK, Kim HS, Park SH, Kim SJ, Cho HD. Endoloop ligation of large pedunculated submucosal tumors (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:556-560. |

| 17. | Sun S, Ge N, Wang C, Wang M, Lü Q. Endoscopic band ligation of small gastric stromal tumors and follow-up by endoscopic ultrasonography. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:574-578. |

| 18. | Kakushima N, Fujishiro M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastrointestinal neoplasms. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:2962-2967. |

| 19. | Ono S, Fujishiro M, Niimi K, Goto O, Kodashima S, Yamamichi N, Omata M. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal squamous cell neoplasms. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:860-866. |