Published online Sep 21, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i35.4494

Revised: May 27, 2010

Accepted: June 3, 2010

Published online: September 21, 2010

The occurrence of pancreatic pleural effusion, secondary to an internal pancreatic fistula, is a rare clinical syndrome and diagnosis is often missed. The key to the diagnosis is a dramatically elevated pleural fluid amylase. This pancreatic pleural effusion is also called a pancreatic pleural fistula. It is characterized by profuse pleural fluid and has a tendency to recur. Here we report a case of delayed internal pancreatic fistula with pancreatic pleural effusion emerging after splenectomy. From the treatment of this case, we conclude that the symptoms and signs of a subphrenic effusion are often obscure; abdominal computed tomography may be required to look for occult, intra-abdominal infection; and active conservative treatment should be carried out in the early period of this complication to reduce the need for endoscopy or surgery.

- Citation: Jin SG, Chen ZY, Yan LN, Zeng Y. Delayed internal pancreatic fistula with pancreatic pleural effusion postsplenectomy. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(35): 4494-4496

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i35/4494.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i35.4494

A pancreatic fistula is a common complication after pancreatic surgery, trauma, and inflammation, etc. However, the emergence of a delayed postoperative internal pancreatic fistula with pancreatic pleural effusion is still relatively rare. Here we report such a case after splenectomy.

A 52-year-old man was admitted to our department for hepatic cirrhosis with splenomegaly and hypersplenism. Physical examination showed a smooth, hard spleen palpated under the left rib margin. Laboratory examinations showed no obvious abnormality except on routine blood examination (white blood count, hemoglobin, and platelet count were 1.90 × 109/L, 65 g/L, and 24 × 109/L, respectively). Abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed hepatic cirrhosis and splenomegaly. Endoscopic examination showed mild esophageal varicose veins without signs of bleeding. Thus splenectomy was conducted and the splenic bed was sewn up with a 4-0 Prolene suture to cover the rough surface of the splenic bed tissue and to prevent subphrenic infection. In the operation, we examined the diaphragm and tail of the pancreas carefully and found no obvious injury. A drainage tube was placed at the left subphrenic fossa. The operation was successful.

During the first 4 d after surgery, the patient recovered smoothly. Amylase in the drainage fluid was normal on the 4th d postoperatively and the drainage tube was removed the following day. Subsequently, however, a fever of unknown origin occurred and fluctuated between 37.5°C and 40°C in the following days, without other abnormal symptoms and signs. Then ultrasound examination of the abdomen, including the portal venous system, a chest X-ray, and blood culture were performed to determine the cause, but no obvious positive results were found initially. We had initially considered the cause was spleen fever.

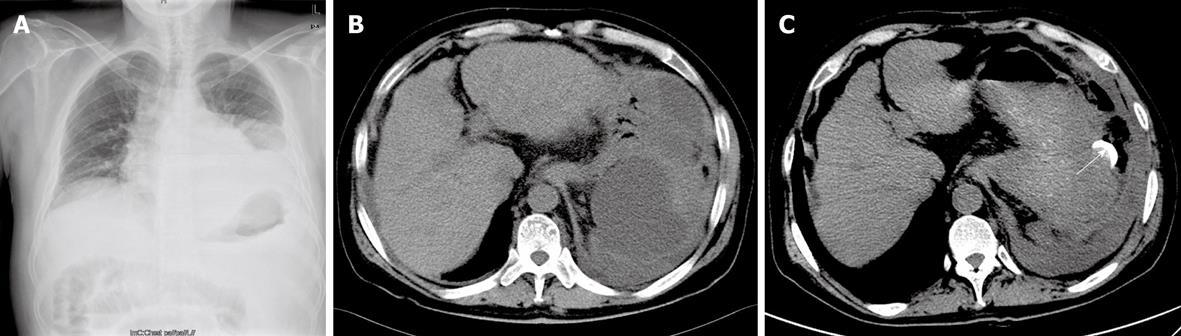

The patient’s condition gradually worsened. Dyspnea and acute heart failure occurred but it was not until the 17th d postoperatively that a left pleural effusion was found in the chest X-ray film (Figure 1A), and a left subphrenic effusion encapsulating about 16 cm × 9 cm was revealed by abdominal CT (Figure 1B). Immediately, abdominal paracentesis and thoracocentesis under ultrasound guidance were conducted, and slightly turbid alutaceous liquid was drained out. Amylase values of the protein-rich fluid from the peritoneal cavity and thoracic cavity were significantly elevated at 19 202 IU/L and 17 531 IU/L, respectively. In the following 20 d, more than 2000 mL sterile fluid were drained from the peritoneal cavity and thoracic cavity (Figure 1C). The patient gradually recovered.

The occurrence of pancreatic pleural effusion, secondary to internal pancreatic fistula, is a rare clinical syndrome and diagnosis is, therefore, often missed. The fluid accumulation is attributed to disruption of the pancreatic duct or to rupture of a pseudocyst. The key to the diagnosis is a dramatically elevated pleural fluid amylase. Effusions in association with acute pancreatitis, esophageal perforation, and thoracic malignancy are important to consider in the differential diagnosis of an elevated pleural fluid amylase but are usually easy to exclude.

The pancreatic duct disruption can also develop posteriorly. Extravasated fluid travels in a cephalad direction through the retroperitoneum to reach the thoracic cavity, or by the lymphatic system and stomata[1-3] of the diaphragm flow into the pleural cavity. Stomata in the peritoneum covering the inferior surface of the diaphragm were first described by von Recklinghausen in 1863. These stomata communicate with lymphatic vessels within the diaphragm. This pancreatic pleural effusion is also called a pancreatic pleural fistula, according to Michael[4]. Pancreatic pleural effusions are typically large and have a tendency to recur. This is in contrast to sympathetic effusions without significant elevated amylase that occur in the setting of acute pancreatitis or secondary to subphrenic abscesses, and tend to be small and self-limiting.

In this case, we supposed that the pathogenesis of the internal pancreatic fistula arose as a result of posterior pancreatic duct rupture. As a minor leakage encapsulated by surrounding tissues, pancreatic leakage was not obvious initially, but it became significant when the inflammation regressed, so a delayed internal pancreatic fistula presented. Because of the short duration of the complication and rapid recovery, CT failed to show the pancreatic pleural fistula, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography[5-7] examination was also not considered necessary. An internal pancreatic fistula with pleural effusion can usually be managed nonoperatively by percutaneous drainage and reoperation is rarely required[8,9].

From the treatment of this case, we have come to some important conclusions: (1) a delayed internal pancreatic fistula can occur postsplenectomy; (2) patients who continue to have a fever and slow clinical progress may require CT of the abdomen to look for occult, intra-abdominal infection accounting for the fever[10]; and (3) active conservative treatment should be carried out in the early period of this complication to reduce the need for endoscopy or surgery.

Peer reviewers: Michael Leitman, MD, FACS, Chief of General Surgery, Beth Israel Medical Center, 10 Union Square East, Suite 2M, New York, NY 10003, United States; Takashi Kobayashi, MD, PhD, Department of Surgery, Showa General Hospital, 2-450 Tenjincho, Kodaira, Tokyo 187-8510, Japan

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Li JC, Yu SM. Study on the ultrastructure of the peritoneal stomata in humans. Acta Anat (Basel). 1991;141:26-30. |

| 2. | Azzali G. The lymphatic vessels and the so-called "lymphatic stomata" of the diaphragm: a morphologic ultrastructural and three-dimensional study. Microvasc Res. 1999;57:30-43. |

| 3. | Abu-Hijleh MF, Habbal OA, Moqattash ST. The role of the diaphragm in lymphatic absorption from the peritoneal cavity. J Anat. 1995;186:453-467. |

| 4. | Michael LS. Exocrine pancreas. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery: the biological basis of modern surgical practice. 17th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders company 2004; 1660. |

| 5. | Safadi BY, Marks JM. Pancreatic-pleural fistula: the role of ERCP in diagnosis and treatment. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:213-215. |

| 6. | Ondrejka P, Siket F, Sugár I, Faller J. Pancreatic-pleural fistula demonstrated by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Endoscopy. 1996;28:784. |

| 7. | Kimura Y, Yamamoto T, Zenda S, Kawamura E, Suzuki E. Pancreatic pleural fistula: demonstration by computed tomography after endoscopic retrograde pancreatography. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:790-793. |

| 8. | Cameron JL, Kieffer RS, Anderson WJ, Zuidema GD. Internal pancreatic fistulas: pancreatic ascites and pleural effusions. Ann Surg. 1976;184:587-593. |

| 10. | Merril TD. Surgical complications. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery: the biological basis of modern surgical practice. 17th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders company 2004; 305. |