Published online Jun 28, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i24.3087

Revised: April 11, 2010

Accepted: April 18, 2010

Published online: June 28, 2010

Self-expanding metal stent (SEMS) placement offers safe and effective palliation in patients with upper gastrointestinal obstruction due to a malignancy. Well described complications of SEMS placement include tumor growth, obstruction, and stent migration. SEMS occlusions are treated by SEMS redeployment, argon plasma coagulation application, balloon dilation, and surgical bypass. At our center, we usually place the second SEMS into the first SEMS if there is complete occlusion by the tumor. We discovered an unusual complication during SEMS redeployment. The guidewire passed through the mesh of the first SEMS and caused the second SEMS to become entangled with the first SEMS. This led to the distortion and malfunction of the second SEMS, which worsened the gastric outlet obstruction. For lowering the risk of entanglement, we studied stone extraction balloon-guided repeat SEMS placement. This is the first report of a SEMS entangled by the mesh of the first SEMS and stone extraction balloon-guided repeat SEMS placement for lowering the risk of this complication.

- Citation: Kim HH, Moon JS, Ryu SH, Lee JH, Kim YS. Stone extraction balloon-guided repeat self-expanding metal stent placement. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(24): 3087-3090

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i24/3087.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i24.3087

In patients presenting with gastric outlet obstruction, upper gastrointestinal malignancies are the source in up to 39% of cases[1]. Surgical resection is the standard of care in patients who lack significant comorbidities[2]. In unresectable patients, gastrojejunostomy remains the standard of care if a surgical intervention is to be undertaken. In those patients with significant comorbidities, the morbidity rate approaches 40%[3], encouraging alternatives to surgery. In patients who are not surgical candidates, enteral stenting offers an attractive option[4]. Self-expanding metal stent (SEMS) has proven itself to be a safe and relatively cost-effective alternative to surgical palliation allowing the patient to be discharged and start postoperative (PO) intake earlier[5]. Complications related to SEMS placement include stent migration, managed by removal of the original SEMS and replacement with a new SEMS, and obstructions due to local disease progression, treated respectively with repeat SEMS placement, argon plasma coagulation application, balloon dilation, and surgical bypass[2]. We usually perform repeat SEMS placement when there is an obstruction after first stenting. Overlapping the second SEMS into the first SEMS is a safe and easy way for resolving stent obstruction. However, repeat SEMS placement can cause a serious problem if a guidewire transverses the mesh of the first SEMS and the second SMES is deployed in the mesh of the first SEMS. It must be extremely rare and happens in specific conditions; we experienced just one case of this serious complication. However, once it has happened, this causes irreversible SEMS entanglement leading to further obstruction. Therefore, it is necessary to lower the risk of SEMS entanglement during repeat SEMS placement. To prevent a guidewire from passing through the mesh of the first SEMS, we devised our stone extraction balloon-guided repeat SEMS placement and applied it to one case successfully.

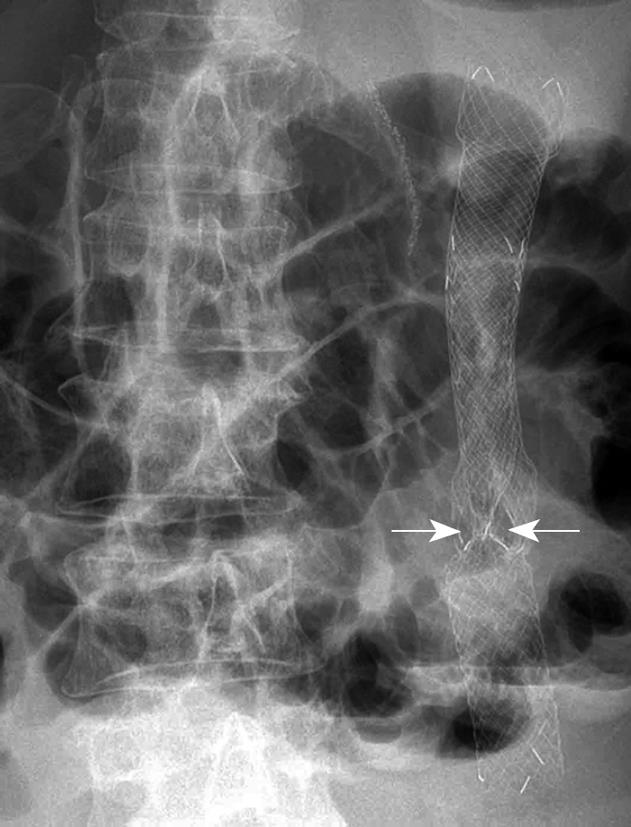

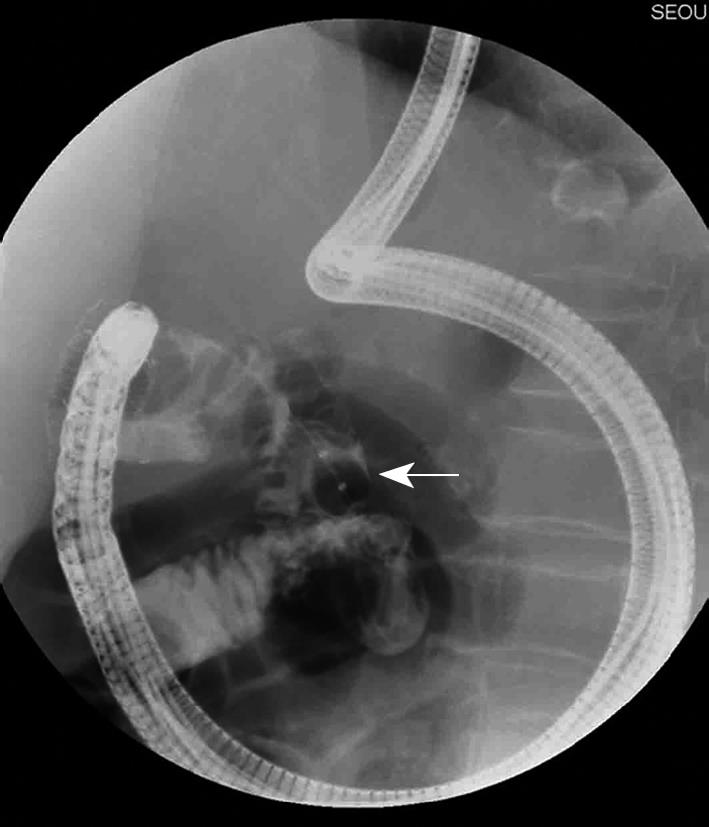

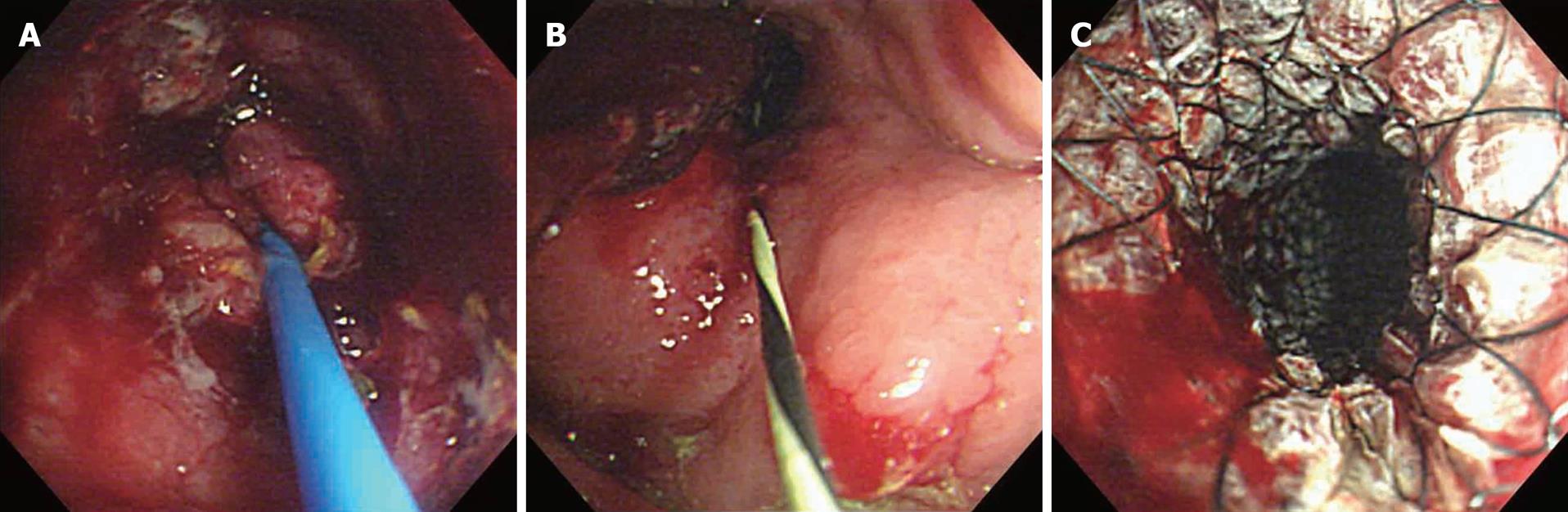

A seventy-year-old woman received an 80 mm long SEMS (Niti-S™ Pyloric uncovered stent, Taewoong Medical, Ilsan, Korea) for relieving gastric outlet obstruction due to advanced gastric cancer. Six months later, she presented with vomiting and abdominal distention. Investigation revealed tumor overgrowth distal to the placed SEMS. We decided to deploy another 120 mm long uncovered SEMS (Niti-S™ Pyloric covered stent, Taewoong Medical, Ilsan, Korea), overlapping the previous one. An endoscopy did not pass the existing stent because the proximal part of the existing SEMS was narrow. Thus, we advanced a guidewire from the proximal part of the first SEMS. After performing repeat SEMS placement, we encountered an unusual complication. The newly deployed SEMS was trapped and unexpanded at the entangled site (Figure 1). The guidewire passed through the mesh of the existing stent and caused the second SEMS to be trapped by the mesh of the first one. Because of this complication the gastric outlet obstruction was not improved. This painful experience made us think of stone extraction balloon-guided repeat SEMS placement to avoid SEMS entanglement in specific conditions; the insertion of a guidewire from the proximal or middle part of the first SEMS guided only by fluoroscopy and the acute angulation of duodenum. Several months later, we faced a similar situation. An eighty-four-year-old woman with an 80 mm long SEMS (Niti-S™ Pyloric uncovered stent, Taewoong Medical, Ilsan, Korea) presented with gastric outlet obstruction symptoms. Investigation found that tumor ingrowth had caused SEMS occlusion. We decided to deploy a 100 mm long covered SEMS (Niti-S™ Pyloric covered stent, Taewoong Medical, Ilsan, Korea) into the existing one. Endoscopy was advanced to the middle part of the first SEMS where tumor ingrowth caused near total occlusion. We used a 15 mm stone extraction balloon (ESCORT II™, Willson Cook, Winston-Salem, USA) before advancing a guidewire. An inflated 15 mm stone extraction balloon was passed through from the middle to the distal part of the existing stent without falling into the mesh and led a guidewire to reach the target area safely (Figures 2 and 3). Repeat SEMS placement was successfully performed without the misguidance of a guidewire (Figure 4).

The endoscopic placement of enteral SEMS relieves malignant gastroduodenal obstruction in the majority of patients, allowing discharge from hospital and the resumption of enteral nutrition[6]. A multi-center trial of patients with gastric outlet obstruction due to malignancy has concluded that enteral stent insertion allows a purely enteral diet to be maintained in up to 92% of patients, with 73% tolerating solid or semi-solid food[7]. Overall, if migration, fracture, tumor ingrowth, erosion, and perforation are taken into account, the global long-term patency rate obtained is 76%[2]. Stent migration occurs more often with covered stents since tumor ingrowth and subsequent incorporation of the stent into the surrounding tissue is less likely. In contrast, recurrent obstruction is more problematic for uncovered stents[8]. About 9% of total patients who received SEMS developed stent occlusion by local tumor growth with progression of the primary disease process[2]. These were treated, respectively, with repeat SEMS placement, argon plasma coagulation application, balloon dilation, and surgical bypass[2]. At our center, we usually perform repeat SEMS placement when there is a stent occlusion by tumor growth. We have performed repeat SEMS placement through endoscopic-fluoroscopic positioning. An endoscope with a working channel is placed at the distal portion of the first SEMS. Under fluoroscopic guidance, a guidewire pre-loaded through a catheter is used to gently cannulate the stenosis. Once the guidewire has passed through the stenosis, the catheter is advanced over the guidewire through the lesion. As soon as the catheter is passed through the stenosis, the guidewire is removed and water soluble contrast medium is injected to document the characteristics and length of the obstruction and to rule out the occurrence of perforation. At this point, it is very important to push and pull a guidewire through the catheter to find the right position. The stent apparatus is passed through the scope, advanced over the first SEMS under endoscopic and fluoroscopic guidance and deployed so that the middle of the stent covers the first SEMS with 2-2.5 cm extending beyond the proximal and distal margins of the obstructing neoplasm.

Repeat SEMS placement is generally safe and does not cause complications. However, in a specific condition, this procedure can result in irreversible SEMS entanglement. SEMS entanglement can happen by the combination of two conditions: acute angulation of the duodenum and stenosis of the first SEMS that prohibits an endoscope from passing through it. Stenosis of the first SEMS makes practice totally dependent on fluoroscopy, and acute angulation causes a guidewire to touch the duodenal wall. These two conditions make it possible for a guidewire to pass through the mesh of the first SEMS. It is definite that the possibility for a guidewire to transverse the mesh depends more on the angle of a guidewire direction to the mesh wall than on the catheter diameter. Because of the acute angulation of the SEMS in the duodenum, this situation can happen in duodenal obstruction treated by repeat SEMS placement, with frequent misinsertion of the guidewire. Although the acute angulation of an SEMS and the duodenum is the major factor responsible for SEMS entanglement, we thought that a thin guidewire was also responsible for this complication. Because the tip of the guidewire is smaller than the pores of the mesh, it can transverse the mesh and misguide the second SEMS under these specific conditions. When it does occur, the entanglement leads the second SEMS remaining unexpanded and causes further occlusion. For avoiding entanglement of two SEMSs, it is important to push forward and pull back a guidewire repeatedly to ensure the correct position of the guidewire, before starting the insertion of a second SEMS. It is also necessary for the deployment of the new stent to be slow and under careful radiologic control, because most stents can be recovered in their own sheath during the deployment maneuvers, when difficulties are encountered. Adding to these important skills, using a stone extraction balloon can be considered instead of using an ordinary guidewire. When inflated, this system is larger than the pores of the mesh, and therefore, the stone extraction balloon is less likely to pass through the mesh. We used three steps to perform stone extraction balloon-guided repeat SEMS placement in the specific conditions mentioned before. First, we advanced the stone extraction balloon distal to the first SEMS. Second, we inserted the guidewire through the stone extraction balloon so that it was placed at the target area. Finally, we placed the second SEMS within the first one following the guidewire. When there was an acute angulation, and an endoscope was not able to pass through the first SEMS, it seemed easier and safer to perform repeat SEMS placement by the guidance of a stone extraction balloon under careful radiologic control with repeat push and pull of a guidewire.

Peer reviewer: Josep M Bordas, MD, Department of Gastroenterology IMD, Hospital Clinic, Llusanes 11-13 at, Barcelona 08022, Spain

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor O'Neill M E- Editor Lin YP

| 1. | Awan A, Johnston DE, Jamal MM. Gastric outlet obstruction with benign endoscopic biopsy should be further explored for malignancy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:497-500. |

| 2. | Phillips MS, Gosain S, Bonatti H, Friel CM, Ellen K, Northup PG, Kahaleh M. Enteral stents for malignancy: a report of 46 consecutive cases over 10 years, with critical review of complications. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:2045-2050. |

| 3. | Medina-Franco H, Abarca-Pérez L, España-Gómez N, Salgado-Nesme N, Ortiz-López LJ, García-Alvarez MN. Morbidity-associated factors after gastrojejunostomy for malignant gastric outlet obstruction. Am Surg. 2007;73:871-875. |

| 4. | Graber I, Dumas R, Filoche B, Boyer J, Coumaros D, Lamouliatte H, Legoux JL, Napoléon B, Ponchon T. The efficacy and safety of duodenal stenting: a prospective multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2007;39:784-787. |

| 5. | Jeurnink SM, van Eijck CH, Steyerberg EW, Kuipers EJ, Siersema PD. Stent versus gastrojejunostomy for the palliation of gastric outlet obstruction: a systematic review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2007;7:18. |

| 6. | Lindsay JO, Andreyev HJ, Vlavianos P, Westaby D. Self-expanding metal stents for the palliation of malignant gastroduodenal obstruction in patients unsuitable for surgical bypass. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:901-905. |

| 7. | Nassif T, Prat F, Meduri B, Fritsch J, Choury AD, Dumont JL, Auroux J, Desaint B, Boboc B, Ponsot P. Endoscopic palliation of malignant gastric outlet obstruction using self-expandable metallic stents: results of a multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2003;35:483-489. |

| 8. | Wong RF, Bhutani MS. Therapeutic endoscopy and endoscopic ultrasound for gastrointestinal malignancies. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2005;5:705-718. |