Published online Apr 7, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i13.1680

Revised: December 19, 2009

Accepted: December 26, 2009

Published online: April 7, 2010

Superwarfarins are a class of rodenticides. Gastrointestinal hemorrhage is a fatal complication of superwarfarin poisoning, requiring immediate treatment. Here, we report a 55-year-old woman with tardive upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage caused by superwarfarin poisoning after endoscopic cold mucosal biopsy.

- Citation: Zhao SL, Li P, Ji M, Zong Y, Zhang ST. Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage caused by superwarfarin poisoning. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(13): 1680-1682

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i13/1680.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i13.1680

Superwarfarins are anticoagulants similar to warfarin. As substitutes for acute rodenticides, superwarfarins are usually the first choice of rodenticide, especially in rural areas. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is a common tool for diagnostic and therapeutic goals. Significant bleeding after cold mucosal biopsy is seldom seen. Here, we report a woman with severe upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage after gastroscopic mucosal biopsy, which is a rare and previously unreported complication of superwarfarin poisoning.

A 55-year-old woman was referred to our hospital for epigastric pain and abdominal distention. Her medical history and physical examination were unremarkable. She had no history of anticoagulation therapy or use of non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs. She came to the outpatient department for further evaluation.

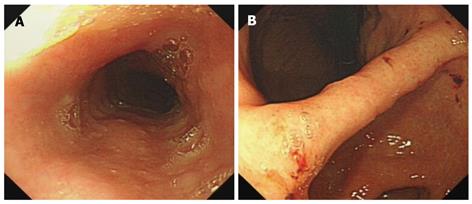

Routine EGD revealed an uneven granular mucosa and several erosion lesions scattering in the stomach, covered with fresh blood crusts (Figure 1). Five mucosal biopsies of the stomach, two from the gastric angle and three from the lesser curvature side of gastric antrum, were performed for pathological analysis and Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) detection. Gastric biopsy specimens revealed atrophic gastritis accompanying intestinal metaplasia. Rapid urease test was negative for H. pylori infection. No active bleeding was seen immediately after endoscopic biopsy and throughout the whole endoscopic procedure. However, she was admitted to the emergency department of our hospital because of hematemesis and melena the next day after EGD examination.

Routine blood test showed 1.7 × 1012 erythrocytes per liter (normal 3.5-4.5 erythrocytes/liter) and 56 g hemoglobin per liter (Table 1). Coagulation function test revealed a prolonged prothrombin time (PT > 180 s) and an activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT = 94.3 s) (Table 1), both of which could be corrected when mixed with normal plasma at a 1:1 ratio. Other blood tests, such as platelet count, fibrinogen, renal function, and liver function, were normal (data not shown).

| Variables | Normal range | Day 2 | Day 4 | Day 8 |

| RBC (1012/L) | 3.5-5.5 | 1.7 | 2.25 | 2.72 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 110-160 | 55 | 74 | 89 |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 11.0-14.0 | > 180 | 16.8 | 13.8 |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time (s) | 35.0-55.0 | 94.3 | 30.5 | 26.9 |

Superwarfarin poisoning was taken into consideration. The patient’s serum and urine specimens were sent to Affiliated 307 Hospital of Academy of Military Sciences of China for toxicology analysis. Laboratory evaluation for some common superwarfarins was performed with the help of reverse-phase high performance enzyme-linked chromatography, showing that the level of brodifacoum and bromadiolone in serum was 1665 ng/mL and 132 ng/mL, respectively, and 216 ng/mL and 15 ng/mL in urine, respectively. The diagnosis of superwarfarin poisoning was confirmed. The patient was also allowed to have intentionally ingested rodenticides to commit suicide 10 d before the routine EGD examination because of severe depression.

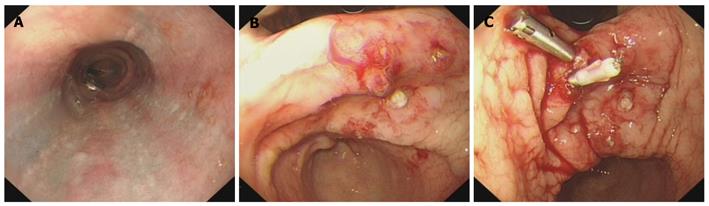

Emergency EGD showed submucosal congestion of the esophagus (Figure 2A), and five hemorrhagic sites in the stomach, which were still bleeding during the endoscopic procedure (Figure 2B). All the bleeding sites were closed with 5 titanium clips to achieve hemostasis (Figure 2C).

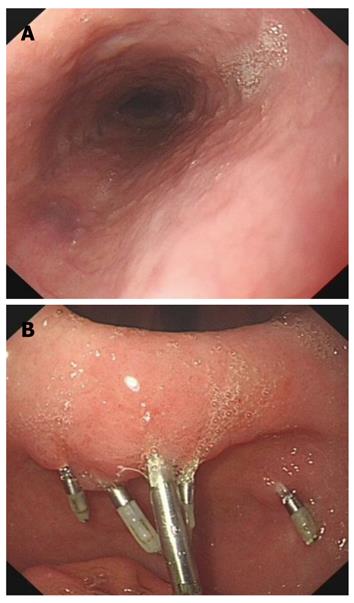

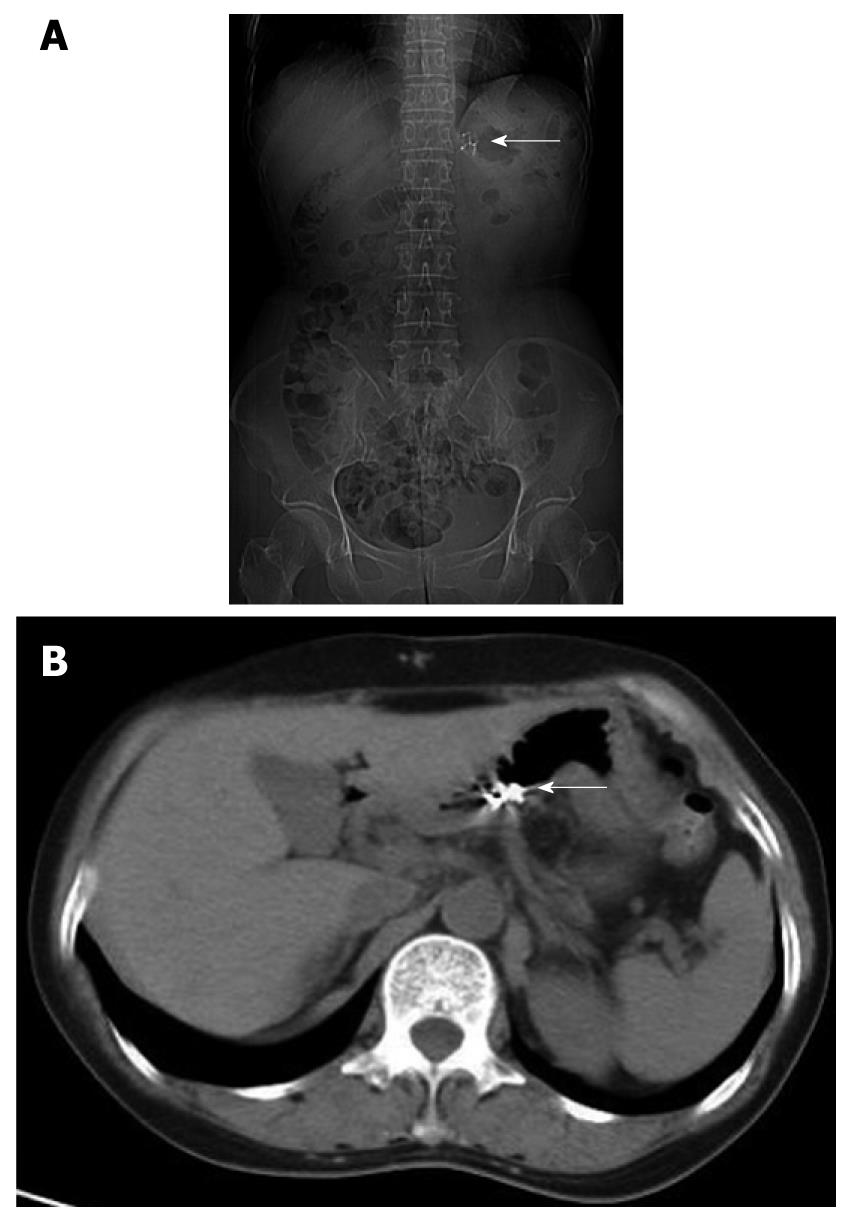

The patient was treated with concentrated red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma and intravenous vitamin K (30 mg/d) for 8 d until her coagulation parameters returned to normal, RBC count and hemoglobin concentration were greatly improved (Table 1). She began to have oral vitamin K1 (30 mg/d) from day 9 after admission. Toxicology analysis on day 7 showed a brodifacoum concentration of 986 ng/mL and a bromadiolone concentration of 36 ng/mL in serum. Brodifacoum (7 ng/mL) could only be detected in the urine specimen. On day 10, EGD showed that the submucosal congestion of esophagus was absorbed with no sign of bleeding in the stomach, and titanium clips in good condition (Figure 3). Plain radiography and CT scanning revealed 5 titanium clips in the stomach (Figure 4).

Two days after the last EGD examination, the patient was discharged from our hospital and oral vitamin K1 was prescribed (10 mg/d) for 1 mo. Weekly PT, prothrombin activity and international normalized ratio measurements were also advised. During the 1-mo following-up after discharge, her coagulation parameters remained normal with no recurrent bleeding.

Superwarfarins, a class of rodenticides with brodifacoum and bromadiolone as their representative, are long acting anticoagulants[1,2] and are 100 times as potent as warfarin. The half life of brodifacoum and bromadiolone can be as long as 24 d[3] or 30 d[1] and 31 d[2], respectively.

Superwarfarins are supposed as the first-line rodenticides all over the world. However, superwarfarin poisoning cases are often reported, especially in rural areas. The number of superwarfarin poisoning cases has also increased in the USA[4,5]. The causes of superwarfarin poisoninginclude accidental exposure, suicide intention and occupational exposure. In addition to oral intake, inhalation and skin absorption can also result in superwarfarin poisoning.

Gastrointestinal hemorrhage is a fatal complication of superwarfarin poisoning, requiring immediate treatment. Treatment modalities include use of antidotes, such as vitamin K1, often requiring a high dose (20-125 mg/d) and a prolonged time because of the long half-life of superwarfarins[2].

Endoscopic treatment for hemostasis is somewhat effective. Due to the extensive bleeding and hemodynamic instability of our patient, blood transfusion and fluid infusion should also be applied to correct the blood volume before emergency endoscopy. In this case, hemostasis was achieved by placing five titanium tips to clip the bleeding sites with the help of an EGD.

In conclusion, with the help of antidotes against superwarfarins and EGD, upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage caused by superwarfarin poisoning after endoscopic cold mucosal biopsy can be successfully and safely controlled.

Peer reviewers: Subbaramiah Sridhar, MB, BS, MPH, FRCP, FRCP, FRCP, FRSS, FRCPC, FACP, FACG, FASGE, AGAF, Section of Gastroenterology, BBR 2544, Medical College of Georgia, 15th Street, Augusta, GA 30912, United States; Michael Leitman, MD, FACS, Chief of General Surgery, Beth Israel Medical Center, 10 Union Square East, Suite 2M, New York, NY 10003, United States

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Laposata M, Van Cott EM, Lev MH. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 1-2007. A 40-year-old woman with epistaxis, hematemesis, and altered mental status. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:174-182. |

| 2. | Pavlu J, Harrington DJ, Voong K, Savidge GF, Jan-Mohamed R, Kaczmarski R. Superwarfarin poisoning. Lancet. 2005;365:628. |

| 3. | Bruno GR, Howland MA, McMeeking A, Hoffman RS. Long-acting anticoagulant overdose: brodifacoum kinetics and optimal vitamin K dosing. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;36:262-267. |

| 4. | Chua JD, Friedenberg WR. Superwarfarin poisoning. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1929-1932. |

| 5. | Watson WA, Litovitz TL, Rodgers GC Jr, Klein-Schwartz W, Reid N, Youniss J, Flanagan A, Wruk KM. 2004 Annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers Toxic Exposure Surveillance System. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23:589-666. |