INTRODUCTION

Mesotherapy and anti-obesity medications are gradually gaining in popularity for purposes of body contouring and weight loss. However, there is a tendency to disregard their various adverse effects. Adverse effects of mesotherapy include bruising, edema, skin necrosis, abdominal hematoma at the site of injection, liver toxicity, demyelination of nerves, and atypical mycobacterial infection[1]. Adverse effects of anti-obesity medications include increase of blood pressure, headache, constipation, and insomnia[2-5].

Until now, there have been no case reports on the intestinal ischemia resulting from mesotherapy only or in combination with anti-obesity medications. We report on an interesting case of ischemic colitis after mesotherapy combined with anti-obesity medications in a 39-year-old female who had no risk factors.

CASE REPORT

A 39-year-old female was admitted to our hospital due to hematochezia persisting for 12 h. She had no previous history of disease. Eight days before admission, she visited an outside anti-obesity clinic where she underwent two days of injection therapy once per day into the subcutaneous fat of the lower abdomen as mesotherapy, and took oral anti-obesity medications twice per day for two days. Medications for mesotherapy were aminophylline, epinephrine, and lidocaine at doses that could not be obtained outside the anti-obesity clinic. Oral anti-obesity medications were fluoxetine 10 mg, ephedrine hydrochloride 10 mg, anhydrous caffeine 50 mg, and green tea powder 250 mg per dose. Six days before admission, the patient stopped taking the mesotherapy and anti-obesity medications due to lower abdominal discomfort and nausea and vomiting. She nearly fasted, except for a small amount of liquid diet, until her admission to our hospital. A sudden onset of hematochezia and lower abdominal pain developed about 12 h prior to admission. She had no history of any medication other than recent mesotherapy and anti-obesity medications. Her vital signs were within normal limits, including normal systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Physical examinations were normal, except for mild tenderness of the left lower abdomen, and fresh bloody stool was revealed with digital rectal examination. Height and body weight were 162 cm and 76.7 kg, respectively, with BMI 29.2 kg/m2. Laboratory test results were within normal limits, including a hemoglobin 14 g/dL, platelet 351 000/uL, prothrombin time 11.3 s, protein C antigen 96% (normal range: 72%-160%), protein S antigen 81% (normal range: 60%-150%), B-type natriuretic peptide 35 pg/mL (normal range: less than 100 pg/mL), except for mildly elevated white blood cells 15 400/mm3. Electrocardiogram, 24-h Holter monitoring, and transthoracic echocardiography all had normal findings. Abdominal CT and CT angiography showed a markedly edematous wall of the entire descending colon and intact abdominal vasculature, including the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries (Figure 1). Colonoscopy showed diffuse edema, erythema, friability, and intramural hemorrhage with multiple active ulcers from the splenic flexure to the sigmoid colon, which were clearly demarcated with adjacent normal segments of colon (Figure 2). Microscopic findings showed portions of colonic mucosa revealing sloughing of the surface epithelium and infiltration of mononuclear inflammatory cells in hyalinized lamina propria (Figure 3). Two days after conservative management with intravenous fluids, electrolytes, and antibiotics composed of ciprofloxacin and metronidazole, bloody stool and abdominal pain markedly decreased and disappeared 6 d later, with complete normalization of leukocytosis. The patient has been followed for 2 years on an outpatient basis without recurrence of specific symptoms.

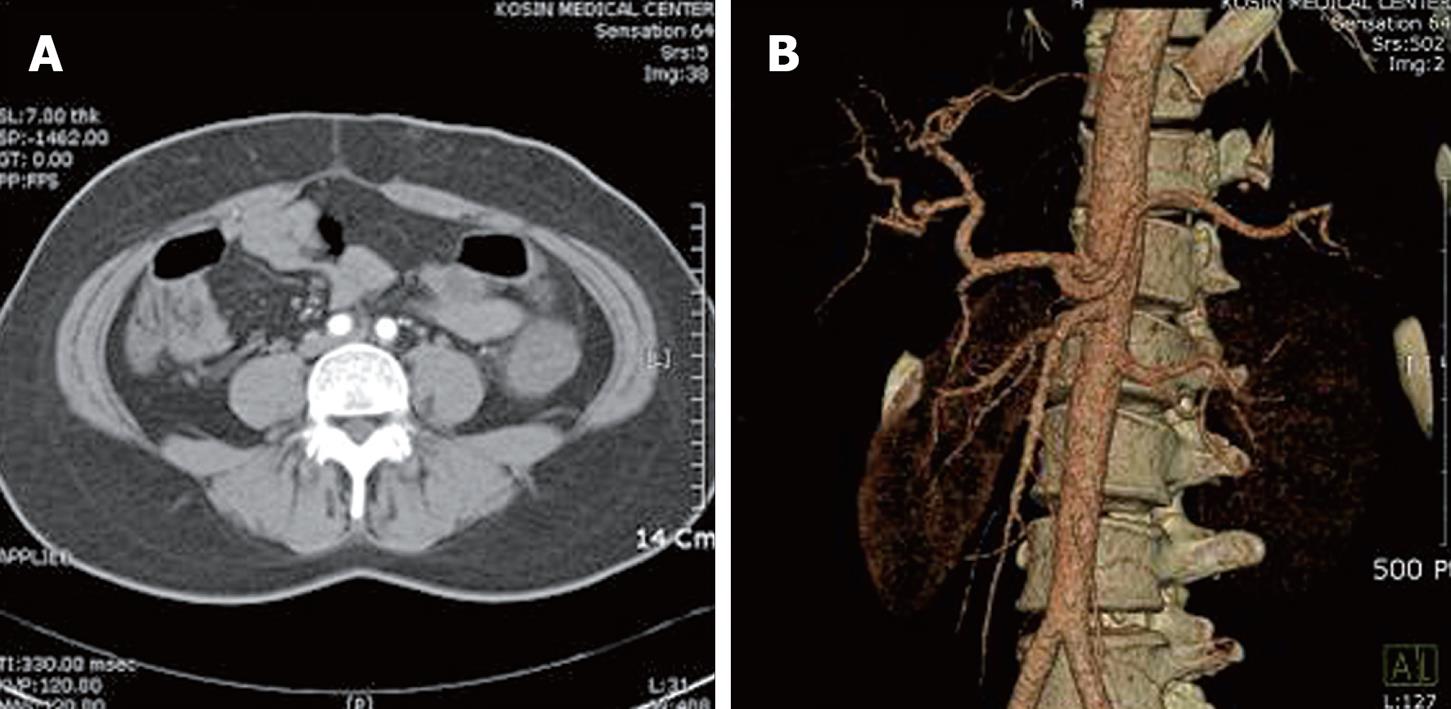

Figure 1 Abdominal computed tomography and angiography.

A: Computed tomography showed diffuse bowel wall edema in the descending colon; B: Angiography showed no evidence of obstruction or stenosis in mesenteric vessels.

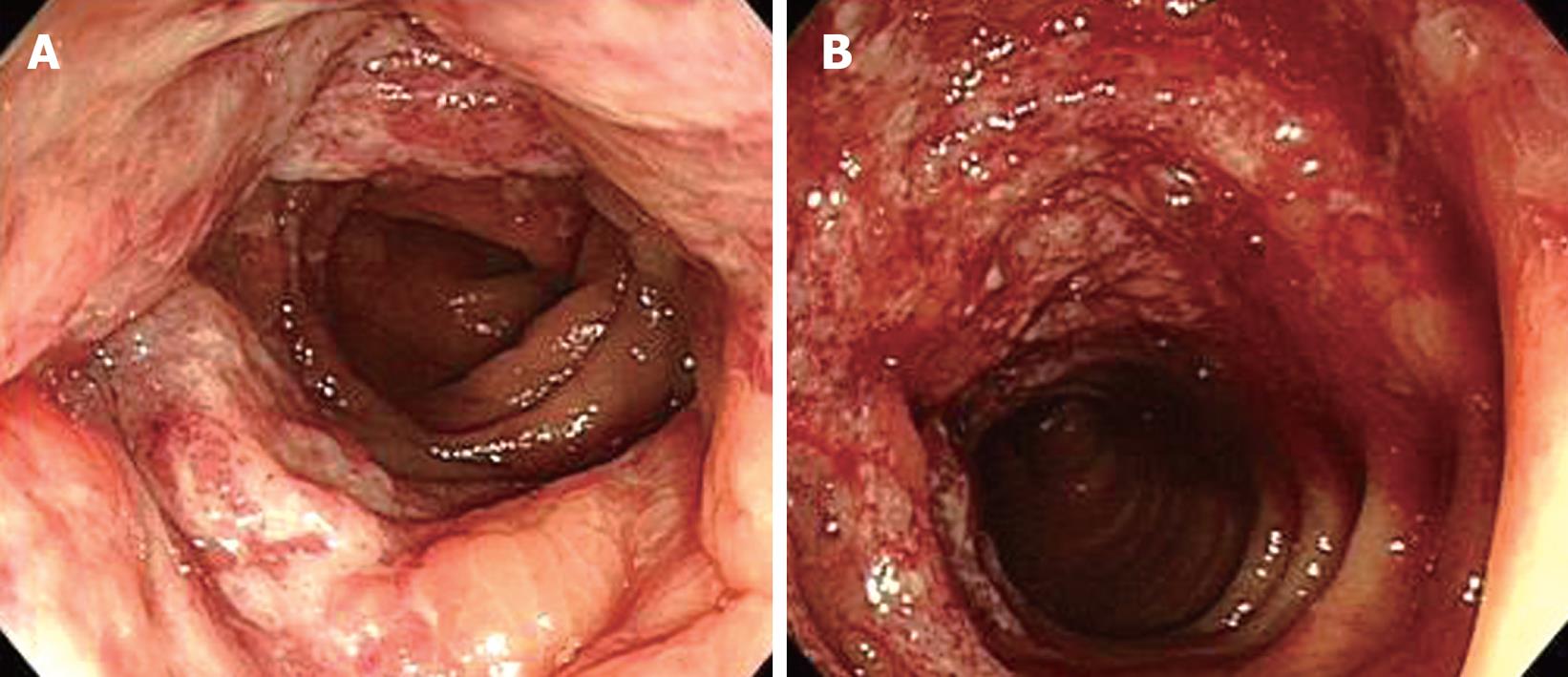

Figure 2 Sigmoidoscopic findings.

Diffuse mucosal edema, erythema (A), friability and submucosal hemorrhage (B) from the splenic flexure to the sigmoid colon are shown.

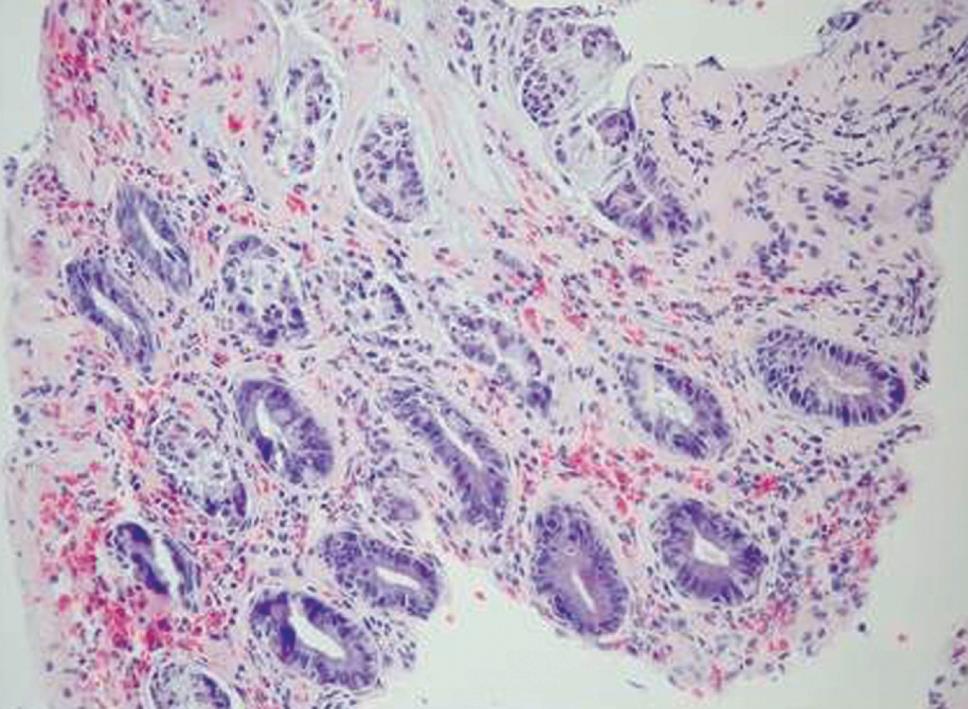

Figure 3 Microscopic findings of colonoscopic biopsy.

Sections showed portions of colonic mucosa revealing sloughing of the surface epithelium and infiltration of mononuclear inflammatory cells in hyalinized lamina propria. (HE, × 200).

DISCUSSION

Ischemic colitis is one of the most common diseases associated with non-obstructive blood vessel disorders. Ischemic colitis is common in people over 50 years old. However, it can develop rarely in women younger than 40 years old through use of oral contraceptives, vasoconstrictors, diuretics, cocaine and anti-depressants, or as a result of irritable bowel syndrome[6-9].

Potential cardiac sources of embolism (CSE) (arrhythmia, structural cardiac abnormality such as valvular heart disease and structural aortic abnormality) were relatively common in patients with ischemic colitis[10,11]. This suggests that when ambulatory ischemic colitis occurs, it is necessary to perform an exhaustive cardiovascular evaluation similar to those performed in other ischemic diseases[11]. The optimal way to detect potential CSE was the combination of electrocardiogram, 24-h Holter monitoring, and transthoracic echocardiography[11,12]. Anticoagulation therapy should also be considered for patients who have CSE[10].

Cases of ischemic colitis in young patients have been reported[12,13] to be associated with hereditary factors such as deficiencies of protein C, protein S, and antithrombin, factor V Leiden mutation, and prothrombin 20210G/A mutation, as well as acquired factors such as antiphospholipid antibodies[13]. The mechanism of ischemic colitis is more often multifactorial[11,12]. Therefore, an interaction between hereditary and acquired factors including the drugs which are used in mesotherapy and anti-obesity medication, is possibly the key to understanding why certain persons develop colonic ischemia at a specific time point especially at a young age[12]. Accordingly, when ischemic colitis develops in young people, we should examine whether such hereditary and acquired factors as causes of it exist or not.

Mesotherapy is a recently introduced treatment that involves delivery of pharmacologic drugs into the mesoderm, which is the layer of fat or connective tissue under the skin. It is commonly used for purposes of body contouring and weight loss. Aminophylline is a common ingredient in mesotherapy that is used for lipolysis. It inhibits phosphodiesterase and activates hydrolysis of adipose tissue[14]. Systemically, it stimulates the medullary respiratory center to induce diuresis and induces catecholamine release from the adrenal medulla[15]. Epinephrine and lidocaine are not commonly used ingredients in mesotherapy. However, we think that they were administered for the purpose of causing local vasoconstriction and for pain relief at the subcutaneous injection site of the lower abdomen, respectively. Although the mesotherapy solution was injected locally into the subcutaneous fat, we think that its systemic effect could not be completely ignored.

Some oral agents are approved by the U.S. FDA as anti-obesity medications for the purpose of long-term use: sibutramine, orlistat, and rimonabant. In addition, anti-obesity medications for short-term use include sympathomimetic amines, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI), ephedrine, and caffeine[2,10,16]. Fluoxetine is an anti-depressant belonging to the SSRIs. Blockage of serotonin uptake in the nerve terminal and amplification of signals sent by serotonin neurons result in decreased food intake[5]. There have been no reported cases of intestinal ischemia induced by use of fluoxetine as a single agent; however, three cases of intestinal ischemia induced by use of fluoxetine in combination with sumatriptan have been reported[3]. Pseudoephedrine is an α-adrenergic agonist and potent vasoconstrictor. It inhibits appetite through release of noradrenaline in sympathetic nerve, and exerts a synergistic action when administered with caffeine[2,10]. Dowd et al[4] reported on 4 female patients aged 37 to 50 who developed ischemic colitis after taking pseudoephedrine. Caffeine promotes secretion of catecholamine and inhibits appetite. Green tea contains caffeine, and therefore exerts effects similar to those of caffeine[17].

In this case, a second colonoscopy during the follow-up period could not be performed due to the patient’s pregnancy and this is a weakness since we don’t know if the findings of the first colonoscopy were resolved or not, although symptoms have completely disappeared.

We think that the potential important environmental factors for ischemic colitis in our patient were aminophylline (by increasing noradrenaline activity and inducing catecholamine release from the adrenal medulla), epinephrine (by acting as a direct vasoconstrictor), fluoxetine (by blocking serotonin uptake and so decreasing food intake and causing dehydration), ephedrine (by releasing noradrenaline in sympathetic nerves), caffeine (by exerting a synergistic action when administered with ephedrine), green tea (by caffeine effects and increasing the action and release of catecholamines), and unidentified hereditary and/or acquired factors might have contributed to the development of ischemic colitis. In addition, reduced body fluid caused by relative fasting and vomiting can be considered as aggravating factors in the development of ischemic colitis. Although two cases of ischemic colitis associated with anti-obesity medications with fenfluramine and phentermine have been reported[18,19], they were not related to the agents prescribed for our patient. Therefore, to the best of our knowledge, our case is the first report in the world on ischemic colitis after mesotherapy combined with anti-obesity medications.

In conclusion, mesotherapy should be taken with great care by both the young and the old, particularly when combined with anti-obesity medications, because it can cause systemic vasoconstriction and result in various side effects, such as ischemic colitis. In addition, dehydration by relative fasting should be avoided during therapy because it can aggravate development of ischemic colitis.