INTRODUCTION

First reported in 1674 by Barbette of Amsterdam[1] and further presented in a detailed report in 1789 by John Hunter[2] as “introssusception”, intussusception represents a rare form of bowel obstruction in the adult, which is defined as the telescoping of a proximal segment of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, called intussusceptum, into the lumen of the adjacent distal segment of the GI tract, called intussuscipiens. Historically, Sir Jonathan Hutchinson was the first to operate on a child with intussusception in 1871[3].

Adult intussusception represents 5% of all cases of intussusception and accounts for only 1%-5% of intestinal obstructions in adults[4]. The condition is distinct from pediatric intussusception in various aspects. In children, it is usually primary and benign, and pneumatic or hydrostatic (air contrast enemas) reduction of the intussusception is sufficient to treat the condition in 80% of the patients. In contrast, almost 90% of the cases of intussusception in adults are secondary to a pathologic condition that serves as a lead point, such as carcinomas, polyps, Meckel’s diverticulum, colonic diverticulum, strictures or benign neoplasms, which are usually discovered intraoperatively[567]. Due to a significant risk of associated malignancy, which approximates 65%[89], radiologic decompression is not addressed preoperatively in adults. Therefore, 70 to 90% of adult cases of intussusception require definite treatment, of which surgical resection is, most often, the treatment of choice[10].

MECHANISM-PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

In adults, the exact mechanism of bowel intussusception is unknown (primary or idiopathic) in 8%-20% of cases and is more likely to occur in the small intestine[41011]. On the other hand, secondary intussusception is believed to initiate from any pathologic lesion of the bowel wall or irritant within the lumen that alters normal peristaltic activity and serves as a lead point, which is able to initiate an invagination of one segment of the bowel into the other[1012]. Schematically, intussusception could be described as an “internal prolapse” of the proximal bowel with its mesenteric fold within the lumen of the adjacent distal bowel as a result of overzealous or impaired peristalsis, further obstructing the free passage of intestinal contents and, more severely, compromising the mesenteric vascular flow of the intussuscepted segment. The result is bowel obstruction and inflammatory changes ranging from thickening to ischemia of the bowel wall.

LOCATION-ETIOLOGY

The most common locations in the gastrointestinal tract where an intussusception can take place are the junctions between freely moving segments and retroperitoneally or adhesionally fixed segments[13]. Intussusceptions have been classified according to their locations into four categories: (1) entero-enteric, confined to the small bowel, (2) colo-colic, involving the large bowel only, (3) ileo-colic, defined as the prolapse of the terminal ileum within the ascending colon and (4) ileo-cecal, where the ileo-cecal valve is the leading point of the intussusception and that is distinguished with some difficulty from the ileo-colic variant[5814].

Intussusceptions have also been classified according to etiology (benign, malignant or idiopathic). In the small intestine, an intussusception can be secondary either to the presence of intra- or extra-luminal lesions (inflammatory lesions, Meckel’s diverticulum, postoperative adhesions, lipoma, adenomatous polyps, lymphoma and metastases) or iatrogenic, e.g. due to the presence of an intestinal tube[15] or even in patients with a gastrojejunostomy[16]. Malignancy (adenocarcinoma) accounts for up to 30% of cases of intussusception occurring in the small intestine[10]. A very rare case from our department’s experience was a 29-year old male patient with a diffuse, small B-cell (Burkitt-like) non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the ileum who developed an ileo-colic intussusception. On the other hand, intussusception occurring in the large bowel is more likely to have a malignant etiology and represents up to 66% of the cases[101217].

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The clinical presentation of adult intussusception varies considerably. The presenting symptoms are nonspecific and the majority of cases in adults have been reported as chronic, consistent with partial obstruction[418]. The classic pediatric presentation of acute intussusception (a triad of cramping abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea and a palpable tender mass) is rare in adults. Nausea, vomiting, gastrointestinal bleeding, change in bowel habits, constipation or abdominal distension are the nonspecific symptoms and signs of intussusception[58].

Intussusception in adults can be further classified according to the presence of a lead point or not[19]: transient non-obstructing intussusception without a lead point has been described in patients with celiac[20] or Crohn’s[21] disease, but is more frequently idiopathic and resolves spontaneously without any specific treatment. On the other hand, intussusception with an organic lesion as the lead point usually presents as a bowel obstruction, persistent or relapsing, necessitating, however, a definite surgical therapy.

DIAGNOSIS-IMAGING

Variability in clinical presentation and imaging features often make the preoperative diagnosis of intussusception a challenging and difficult task. Reijnen et al[22] reported a preoperative diagnostic rate of 50%, while Eisen et al[17] reported a lower rate of 40.7%.

Plain abdominal films are typically the first diagnostic tool, since in most cases the obstructive symptoms dominate the clinical picture. Such films usually demonstrate signs of intestinal obstruction and may provide information regarding the site of obstruction[1723]. Upper gastrointestinal contrast series may show a “stacked coin” or “coil-spring” appearance, while a barium enema examination may be useful in patients with colo-colic or ileo-colic intussusception, during which a “cup-shaped” filling defect or “spiral” or “coil-spring” appearances are characteristically demonstrated[172425].

Ultrasonography is considered a useful tool for the diagnosis of intussusception, both in children and in adults[2627]. The classical imaging features include the “target” or “doughnut” signs on the transverse view and the “pseudo-kidney” sign or “hay-fork” sign in the longitudinal view[2728]. Undoubtedly, this procedure requires handling and interpretation by an experienced radiologist, in order to confirm the diagnosis. However, obesity and the presence of massive air in the distended bowel loops limit the image quality and the subsequent diagnostic accuracy.

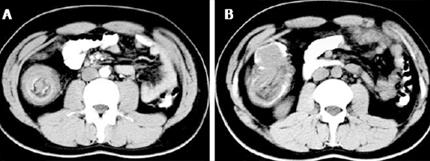

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) is currently considered as the most sensitive radiologic method to confirm intussusception, with a reported diagnostic accuracy of 58%-100%[4122930313233]. The characteristic features of CT scan include an unhomogeneous “target” or “sausage”- shaped soft- tissue mass with a layering effect (Figure 1); mesenteric vessels within the bowel lumen are also typical[10]. A CT scan may define the location, the nature of the mass, its relationship to surrounding tissues and, additionally, it may help staging the patient with suspected malignancy causing the intussusception[17]. In a recent interesting report by Kim et al[19], abdominal CT was able to distinguish between intussusception without a lead point (features: no signs of proximal bowel obstruction, target-like or sausage-shaped mass, layering effect) from that with a lead point (features: signs of bowel obstruction, bowel wall edema with loss of the classic three-layer appearance due to impaired mesenteric circulation and demonstration of the lead mass), and this may help reducing the number of unnecessary surgical interventions.

Figure 1 Abdominal computed tomography in adult intussusception.

A: The characteristic “target”-shaped soft-tissue mass with a layering effect of a 29-year old male patient with a diffuse, small B-cell (Burkitt-like) non Hodgkin lymphoma of the ileum who developed an ileo-colic intussusception; B: A “sausage”-shaped soft tissue mass in the ascending colon of the same patient.

DIAGNOSIS-ENDOSCOPY

Flexible endoscopy of the lower GI tract is considered invaluable in evaluating cases of intussusception presenting with subacute or chronic large bowel obstruction[10]. Confirmation of the intussusception, localization of the disease and demonstration of the underlying organic lesion serving as a lead point are the main benefits of endoscopy. Snare polypectomy is not advisable in individuals with chronic intussusception presenting with a polypoid mass on barium or endoscopic examination, due to the high risk of perforation occurring in a background of chronic tissue ischemia and possible necrosis of the intussuscepted bowel segment’s wall[3435]. In the case of a lipoma as a lead point of an intussusception (Figure 2), typical colonoscopic features include a smooth surface, the “cushion sign” or pillow sign” (forcing the forceps against the lesion results in depression of the mass) and the “naked fat sign” (fat extrusion during biopsy)[363738].

Figure 2 Colonoscopy.

Revealing the presence of the inverted terminal ileum (intussusceptum) in the ascending colon (intussuscipiens) in a patient with an ileo-cecal intussusception due to an ileal lipoma.

SURIGICAL TREATMENT

Due to the fact that adults present with acute, subacute, or chronic nonspecific symptoms[9], the initial diagnosis is missed or delayed and is established only when the patient is on the operating table (Figure 3). Most surgeons accept that adult intussusception requires surgical intervention because of the large proportion of structural anomalies and the high incidence of occurring malignancy. However, the extent of bowel resection and the manipulation of the intussuscepted bowel during reduction remain controversial[10]. In contrast to pediatric patients, where intussusception is primary and benign, preoperative reduction with barium or air is not suggested as a definite treatment for adults[101739].

Figure 3 Intraoperative findings.

A: Thickened, congested and inflamed terminal ileum with proximal small bowel obstruction in a 75-year old woman with ileo-colonic intussusception; B: The surgical specimen after the en bloc resection of the terminal ileum and the ascending colon in the same patient; C: The cause of the intussusception was a lipoma of the ileo-cecal valve (arrow).

The theoretical risks of preliminary manipulation and reduction of an intussuscepted bowel include: (1) intraluminal seeding and venous tumor dissemination, (2) perforation and seeding of microorganisms and tumor cells to the peritoneal cavity and (3) increased risk of anastomotic complications of the manipulated friable and edematous bowel tissue[45101722]. Moreover, reduction should not be attempted if there are signs of inflammation or ischemia of the bowel wall[33]. Therefore, in patients with ileo-colic, ileo-cecal and colo-colic intussusceptions, especially those more than 60 years of age, due to the high incidence of bowel malignancy as the underlying etiologic factor, formal resections using appropriate oncologic techniques are recommended, with the construction of a primary anastomosis between healthy and viable tissue[81017223840]. Azar et al[4] report that, for right-sided colonic intussusceptions, resection and primary anastomosis can be carried out even in unprepared bowels, while for left-sided or rectosigmoid cases resection with construction of a colostomy and a Hartmann’s pouch with re-anastomosis at a second stage is considered safer, especially in the emergency setting.

However, when a preoperative diagnosis of a benign lesion is safely established, the surgeon may reduce the intussusception by milking it out in a distal to proximal direction[40], allowing for a limited resection. Wang et al[41] report that for enteric intussusceptions due to benign lesions, reduction and limited resection resulted in non-recurrence of intussusception. In patients with a risk of a short bowel syndrome due to multiple small intestinal polyps causing intussusception, such as Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, a combined approach with limited intestinal resections and multiple snare polypectomies should be mandatory[42]. Moreover, in patients complicated with postoperative bowel obstruction due to an intussusception, reduction is also recommended, provided that the bowel appears non-ischemic and viable[4].

Finally, several reports have been published regarding the laparoscopic approach of adult intussusception, due to benign and malignant lesions of the small and large bowel[4344454647484950515253]. Laparoscopy has been used successfully in selected cases, depending on patients’ general status and availability of surgeons with sufficient laparoscopic expertise. After establishing the diagnosis of intussusception and the underlying disease laparoscopically, reduction and/or en bloc resection can be performed with the same method.

CONCLUSION

Adult bowel intussusception is a rare but challenging condition for the surgeon. Preoperative diagnosis is usually missed or delayed because of nonspecific and often subacute symptoms, without the pathognomonic clinical picture associated with intussusception in children. Abdominal CT is considered as the most sensitive imaging modality in the diagnosis of intussusception and distinguishes the presence or absence of a lead point. Due to the fact that adult intussusception is often frequently associated with malignant organic lesions, surgical intervention is necessary. Treatment usually requires formal resection of the involved bowel segment. Reduction can be attempted in small bowel intussusceptions provided that the segment involved is viable or a malignancy is not suspected.