INTRODUCTION

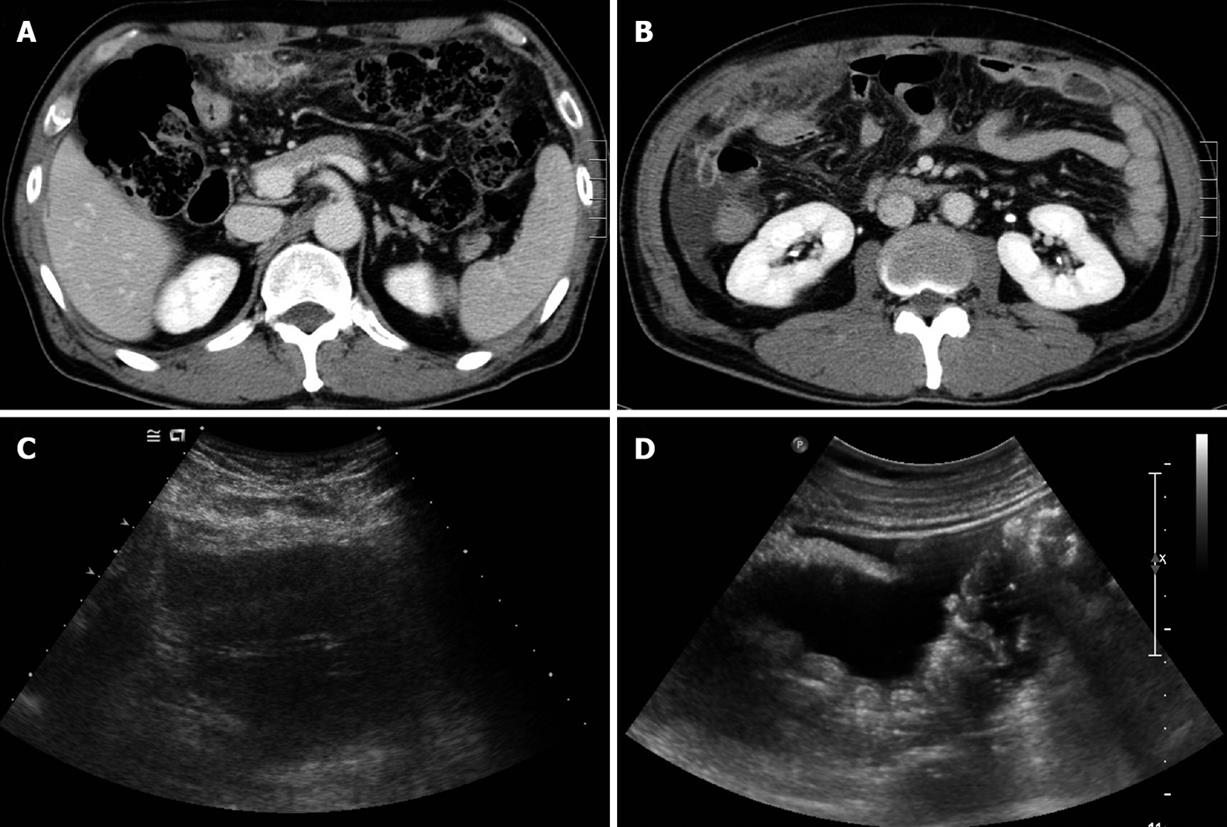

Figure 1 Abdominal computed tomography (CT) and ultrasonography (US).

A: Initial abdominal CT revealed a mass-like lesion of about 7 cm × 3 cm at the greater omentum; B: Abdominal CT follow-up after 1 wk antibiotic therapy showed an increased omental mass lesion, with a shift to the right lower abdomen, and ascites; C: Abdominal US showed a heterogeneous echoic mass at the greater omentum, and ascites; D: Multiple round nodules at the peritoneum and ascites.

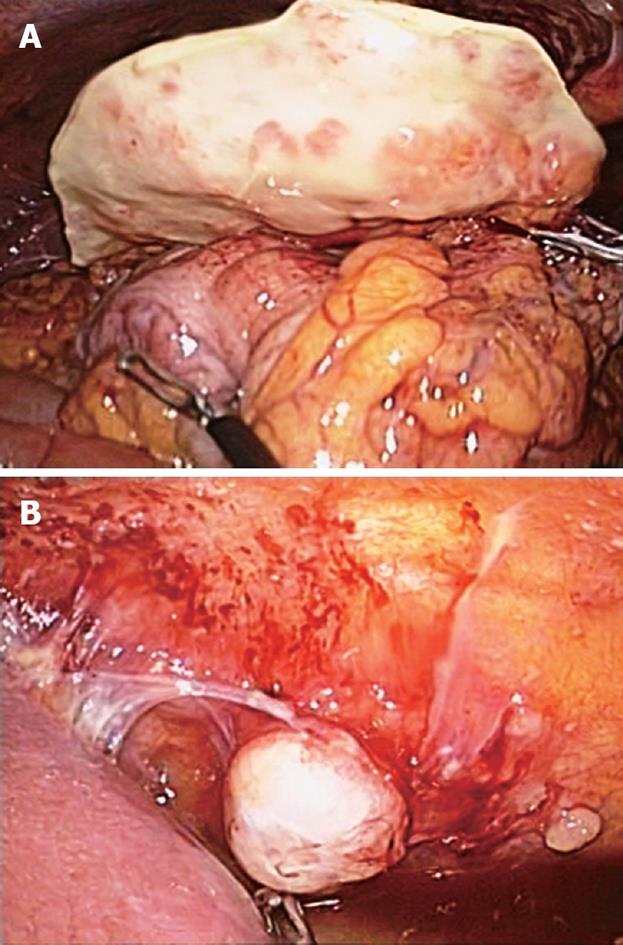

Figure 2 Laparoscopic findings.

A: Greater omental mass of 8 cm × 3.3 cm with coarsely nodular surface; B: Variable-sized metastatic nodules adhered to the parietal peritoneum.

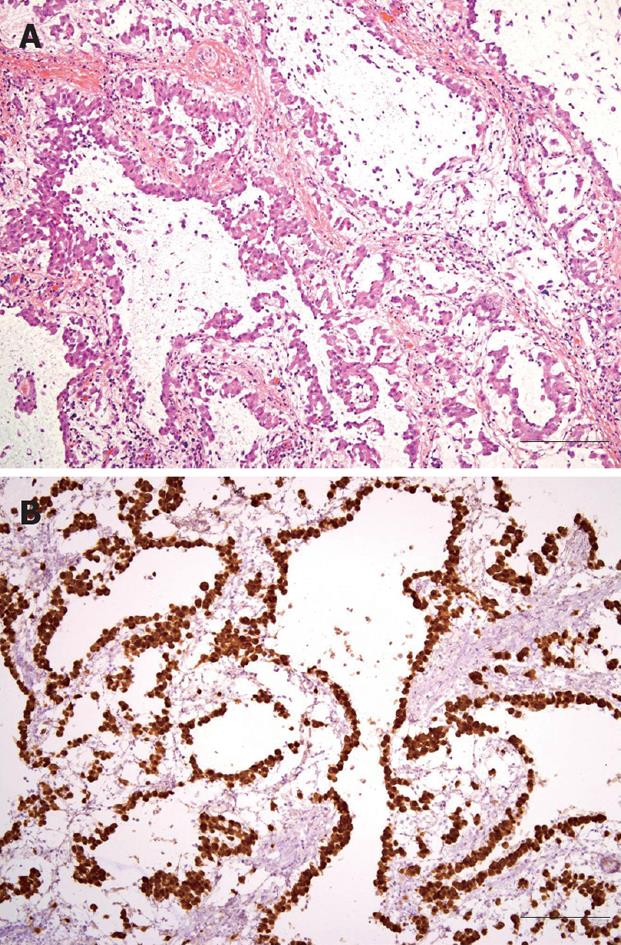

Figure 3 Photomicrographs of laparoscopically resected omental mass.

A: Proliferating epithelioid tumor cells formed tubular, cystic or papillary structures (HE, × 100, bar 100 μm); B: Tumor cells were strongly positive for calretinin upon immunohistochemical staining (× 100, bar 100 μm).

Malignant mesothelioma originates from the mesothelial lining cells of serous cavities. The disease develops most commonly in the pleura, but the peritoneum is involved in 20%-40% of cases[1-4]. Besides its rarity, the disease has no specific clinical or radiological manifestations, therefore, diagnosis is very difficult in the absence of a history of exposure to asbestos[4]. Usually, it manifests as multiple peritoneal nodules or plaques, which may later coalesce to produce diffuse neoplastic thickening of the peritoneum, with encasement of the abdominal viscera. However, a solid mass-like presentation is unusual, and furthermore, primary greater omental tumor is rare. Only a few cases of malignant mesothelioma of the greater omentum have been reported in the English-language literature[5,6]. The omentum is composed mainly of adipose tissue; however, tumors that arise from adipose tissue are less common than smooth muscle tumors, and those that originate from the mesothelial lining are very rare[7,8].

We report here a case of primary malignant mesothelioma that originated from the greater omentum, which manifested as omental infarction.

CASE REPORT

A 54-year-old Korean man was admitted to Gyeongsang National University Hospital because of severe abdominal pain of sudden onset. He had been suffering from vague abdominal pain of unknown cause during the previous 3 mo. He was given thorough medical examinations including abdominal ultrasonography (US) and computed tomography (CT) at several hospitals and clinics, but no cause for abdominal pain had been found. On the day prior to admission, the pain exacerbated suddenly and did not subside with analgesics. The patient was working at a construction company as a chief executive officer but had no apparent history of exposure to asbestos. He had diabetes mellitus controlled with an oral hypoglycemic agent but had no specific family history. He was a nonsmoker and denied drinking alcohol. He looked very nervous and agitated. An indistinct mass-like lesion was palpated, which showed severe tenderness in the upper abdomen. The blood count was normal. Serum glucose was 252 mg/dL (normal range: 70-110 mg/dL), total protein 5.8 g/dL (6.4-8.3 g/dL), albumin 3.1 g/dL (3.4-4.8 g/dL), and C-reactive protein 252 mg/L (0-5 mg/L), but there were no remarkable abnormalities in the other biochemical tests including renal and hepatic function tests. Cancer antigen 125 (CA 125) was 186.7 U/mL (0-5 U/mL). A chest X-ray film was normal, while abdominal sonography and CT revealed an ill-defined mass with heterogeneous echogenicity/attenuation, about 3 cm × 7 cm in size, located in the greater omentum, and a little ascites in the peri-hepatic space (Figure 1). Diagnostic paracentesis of ascites yielded polymorphonuclear neutrophil (PMN)-dominant exudates (white blood cells 2525/mm3, PMN 79%, protein 4.4 g/dL, glucose 234 mg/dL, lactate dehydrogenase 136 U/L). Broad-spectrum antibiotics and analgesics were given for omental infarction with superimposed infection, which resulted in symptomatic improvement. However, the imaging studies after administration of antibiotics for 1 wk showed increased mass size and ascites. Laparoscopic surgery was performed and an 8 cm × 3.3 cm greater-omental mass was found (Figure 2A), with a moderate amount of turbid ascites. Multiple, variable-sized, nodular lesions were scattered diffusely on the surface of the parietal peritoneum, mesentery, diaphragm, and pelvic cavity wall (Figure 2B). No visceral neoplastic lesion was detected. Partial omentectomy and excisional biopsy of nodules were performed. The main omental mass and nodules were composed of proliferating epithelioid cells that showed tubular, cystic or papillary structures. The tumor cells were strongly positive for calretinin (Figure 3), cytokeratin and vimentin, and negative for S-100 and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) upon immunohistochemistry. Diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma was made based on histopathological findings.

The patient recovered uneventfully and was referred to an oncologist for adjuvant therapy. He underwent eight cycles of treatment with pemetrexed and cisplatin. Serum CA 125 after three cycles of chemotherapy decreased to 14.9 U/mL, and positron emission tomography performed after six cycles showed no demonstrable abnormal fluorodeoxyglucose uptake. He has been followed every 3 mo on an outpatient basis after completion of eight cycles of palliative therapy. He is alive and well almost 14 mo after operation.

DISCUSSION

The occurrence of mesothelioma is known to be associated with environmental factors and carcinogens. The association between mesothelioma and asbestos exposure was first reported by Wagner et al[9] in 1960. However, the relationship between peritoneal mesothelioma and asbestos is less obvious than that of pleural mesothelioma[10]. Liu et al[6] also have reported a non-asbestos-related primary mesothelioma of the greater omentum. Another causative etiology is the simian virus 40 (SV40) TAG sequences[11]. A multi-institutional international study has revealed that mesothelioma frequently expresses SV40 TAG sequences[12]. Although our patient had no history of direct exposure to asbestos, he worked in a construction company, so that asbestos could not be excluded as a possible etiological factor. Unfortunately, SV40 studies were not performed in our case.

Primary greater omental tumors are rare, while metastatic tumors in the greater omentum are not uncommon. Several types of primary greater omental tumor have been reported: leiomyosarcoma, hemangiopericytoma, myosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, leiomyoma, leiomyoblastoma, lipoma, fibroma, mesothelioma, and endothelioma[13-16]. In particular, greater omental malignant mesothelioma is very uncommon.

Although patients with primary greater omental tumors may be asymptomatic, most present with abdominal discomfort, nausea, early satiety, weight loss, and a palpable abdominal mass[5,13]. Our patient presented with a greater omental mass with severe pain and PMN-dominant exudative ascites. Furthermore, he showed symptomatic improvement with antibiotic therapy. These findings made us suspect initially complicated omental infarction, making preoperative diagnosis difficult. US and CT of the abdomen can provide important information during the diagnostic process, as in the present case. Short-term follow-up imaging showed no improvement with regard to omental mass and ascites despite symptomatic amelioration, and we therefore decided to perform a laparoscopy to make a definitive diagnosis.

A definitive diagnosis can be established only by laparoscopy or open surgery with biopsy. Histological examination may reveal an epithelial, sarcomatoid, or biphasic pattern[17]. Epithelial-type neoplasms account for 75% of cases and vary from a relatively well-differentiated tumor with a tubulopapillary pattern to solid sheets of rounded or polygonal cells. This type may mimic carcinoma, such that the distinction between epithelioid mesothelioma and metastatic carcinoma, particularly adenocarcinoma, is perhaps the most frequently encountered diagnostic dilemma[18]. The sarcomatoid-type neoplasms also may be indistinguishable from fibrosarcoma upon histology alone. Immunohistochemistry can be helpful in differential diagnosis of sarcoma and adenocarcinoma. Positive immunoreactivity for calretinin markedly increases the accuracy of diagnosis[18-21]. Mesothelioma cells are diffusely positive for calretinin, cytokeratin and epithelial membrane antigen, and negative for S-100 protein, Leu-M1, CEA, thrombomodulin and placental alkaline phosphatase[22]. The tumor cells in our case also showed positive immunoreactivity for calretinin, cytokeratin and vimentin, but were negative for S-100 and CEA.

The prognosis of this malignant tumor is extremely poor because of the lack of effective treatment, with most patients dying within 1 year of diagnosis[3]. Retrospective studies have shown that median survival after palliative surgery and systemic and/or intraperitoneal chemotherapy is about 1 year, ranging from 9 to 15 mo[23-25]. Recently, however, several independent phase I/II prospective trials have reported improved survival with an intensive loco-regional treatment strategy, including cytoreductive surgery along with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy in the form of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy, with or without early postoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy[23]. The median survival after aggressive surgery combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy has approached 5 years and seems to improve with subsequent reports[22,23,26-28]. Meanwhile, Vogelzang et al[29] have demonstrated in a multicenter, controlled, randomized phase III trial that pemetrexed-cisplatin is the gold standard for the non-operable malignant pleural mesothelioma. The combination of pemetrexed and cisplatin chemotherapy yielded an objective response in the present case.

Yan et al[28] have found by multivariate analysis that a small nuclear size is the only good independent prognostic determinant. The 3-year survival rate with a nuclear size of 10-20, 21-30, 31-40 and > 40 μm were 100%, 87%, 27% and 0%, respectively. The present patient survived for 14 mo without clinical and radiological evidence of recurrence, but his prognosis was poor because he was only able to undergo palliative surgery, despite his cells having a small nuclear size. We recommend that primary omental mesothelioma should be included in differential diagnosis of cases of omental infarction, despite its rarity.