Published online Aug 14, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3793

Revised: July 2, 2009

Accepted: July 9, 2009

Published online: August 14, 2009

AIM: To investigate the meaning of lymphovascular invasion (LVI) in rectal cancer after neoadjuvant radiotherapy.

METHODS: A total of 325 patients who underwent radical resection using total mesorectal excision (TME) from January 2000 to January 2005 in Beijing cancer hospital were included retrospectively, divided into a preoperative radiotherapy (PRT) group and a control group, according to whether or not they underwent preoperative radiation. Histological assessments of tumor specimens were made and the correlation of LVI and prognosis were evaluated by univariate and multivariate analysis.

RESULTS: The occurrence of LVI in the PRT and control groups was 21.4% and 26.1% respectively. In the control group, LVI was significantly associated with histological differentiation and pathologic TNM stage, whereas these associations were not observed in the PRT group. LVI was closely correlated to disease progression and 5-year overall survival (OS) in both groups. Among the patients with disease progression, LVI positive patients in the PRT group had a significantly longer median disease-free period (22.5 mo vs 11.5 mo, P = 0.023) and overall survival time (42.5 mo vs 26.5 mo, P = 0.035) compared to those in the control group, despite the fact that no significant difference in 5-year OS rate was observed (54.4% vs 48.3%, P = 0.137). Multivariate analysis showed the distance of tumor from the anal verge, pretreatment serum carcinoembryonic antigen level, pathologic TNM stage and LVI were the major factors affecting OS.

CONCLUSION: Neoadjuvant radiotherapy does not reduce LVI significantly; however, the prognostic meaning of LVI has changed. Patients with LVI may benefit from neoadjuvant radiotherapy.

- Citation: Du CZ, Xue WC, Cai Y, Li M, Gu J. Lymphovascular invasion in rectal cancer following neoadjuvant radiotherapy: A retrospective cohort study. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(30): 3793-3798

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i30/3793.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.3793

Currently, the treatment of rectal cancer has stepped into a new era of multimodality therapy[1]. Neoadjuvant therapy, including preoperative radiotherapy (RT) or radiochemotherapy (RCT), has become a standard regimen for locally advanced rectal cancer[2]. There have been growing concerns in recent years about the pathologic evaluation of rectal cancer after neoadjuvant therapy, since the pathologic stage (ypTNM) is now significantly different from its original meaning[34]. Due to neoadjuvant therapy, a considerable number of patients experience tumor regression or downstaging, and a minority of patients experience a complete pathologic response (CPR)[5]. However, the problem is that there are still few favorable pathological indicators to reflect and predict the clinical consequence of rectal cancer after neoadjuvant therapy.

Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) has been widely acknowledged as a useful independent pathological indicator for predicting prognosis, as well as a good index to guide postoperative therapy in colorectal cancer. Patients with LVI usually have a higher chance of disease progression and poorer prognosis[6–8]. The NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network) guideline recommended LVI as a high risk factor of disease advance for colon cancer after surgery[9]. For rectal cancer, LVI is also a crucial high risk factor for recurrence post transanal local resection[10]. However, it has still to be established whether LVI has the same predictive meaning and clinical significance for patients with rectal cancer undergoing preoperative radiation. Does the biological behavior of the cancer cells involved in the blood or lymphatic vessels change after radiation? This is the issue we focus on.

Data from all consecutive patients with resectable rectal carcinoma treated in our hospital from January 2000 to January 2005 were collected retrospectively. Among them, we selected eligible patients according to the following criteria: (1) resectable rectal cancer 12 cm or less from the anal verge; (2) evaluated by endorectal ultrasound (ERUS) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) before treatment; (3) histologically identified primary carcinoma of the rectum; (4) no clinical evidence of distant metastases; (5) transabdominal radical resection based on the principle of total mesorectal excision (TME); (6) R0 resection.

Exclusion criteria were: (1) patients who underwent concurrent RCT; (2) patients with CPR after neoadjuvant radiotherapy; (3) patients with synchronous tumors or history of other malignant tumors within 5 years; (4) familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and hereditary non-polyposis colorectal carcinoma (HNPCC); (5) died of complications or other non-cancer related reasons.

In total 325 patients were included (Table 1). All included patients were divided into a preoperative radiotherapy (PRT) group (n = 103) and a control group (n = 222), according to whether or not they underwent neoadjuvant radiation. There was no statistically significant difference in the gender, age, tumor location, preoperative serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level, pathologic stage and LVI between the two groups (Table 1). The conditions of histological differentiation and pretreatment stage (by imaging) were better in the control group, which implied a potentially better prognosis of patients in the control group. But the following multivariate analysis demonstrated that these two factors were not the major factors affecting the clinical consequence, so we considered the patients in the two groups to be comparable. Furthermore, we believe it more reasonable to investigate the influence of LVI on clinical consequence under the same pathologic stage rather than the same pretreatment stage in the two groups, so it was inevitable that the pretreatment stage of the PRT group was later because of tumor-downstaging after neoadjuvant radiotherapy.

| PRT n = 103 | Control n = 222 | P value | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 62 | 130 | 0.875 |

| Female | 41 | 92 | |

| Age (yr)1 | 56 (52-61) | 57 (53-64) | 0.232 |

| Distance of tumor from anal verge | |||

| < 5 cm | 35 | 53 | 0.061 |

| 5-12 cm | 68 | 169 | |

| Surgery | |||

| APR | 27 | 55 | 0.564 |

| LAR | 71 | 161 | |

| CR | 5 | 6 | |

| Preoperative serum CEA level | |||

| Normal | 52 | 121 | 0.691 |

| Abnormal | 35 | 65 | |

| Unknown | 16 | 36 | |

| Pretreatment TNM stage (%) | |||

| I (T1-2 N0) | 0 (0) | 43 (19.4) | < 0.01 |

| IIA (T3 N0) | 25 (24.3) | 63 (28.4) | |

| IIB (T4 N0) | 4 (3.9) | 5 (2.3) | |

| IIIA (T1-2 N1) | 3 (2.9) | 8 (3.6) | |

| IIIB (T3-4 N1) | 33 (32.0) | 43 (19.4) | |

| IIIC (AnyT N2) | 38 (36.9) | 60 (27.0) | |

| Pathologic TNM stage (%) | |||

| I (T1-2 N0) | 35 (34.0) | 55 (24.8) | 0.377 |

| IIA (T3 N0) | 27 (26.2) | 62 (27.9) | |

| IIB (T4 N0) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (5.0) | |

| IIIA (T1-2 N1) | 6 (5.8) | 7 (3.2) | |

| IIIB (T3-4 N1) | 18 (17.5) | 45 (20.3) | |

| IIIC (AnyT N2) | 16 (15.5) | 52 (23.4) | |

| Histological differentiation (%) | |||

| High | 4 (3.9) | 29 (13.1) | < 0.01 |

| Moderate | 70 (68.0) | 156 (70.3) | |

| Poor | 24 (23.3) | 27 (12.2) | |

| Mucinous and signet | 5 (4.9) | 10 (4.5) | |

| LVI (%) | |||

| Present | 22 (21.4) | 58 (26.1) | 0.353 |

| Absent | 81 (78.6) | 164 (73.9) | |

| Disease progression (%) | |||

| Local Recurrence | 6 (5.8) | 32 (14.4) | 0.025 |

| Distant Metastasis | 22 (21.4) | 47 (21.2) | 0.969 |

| Death | 24 (23.3) | 66 (29.7) | 0.228 |

All included patients underwent ERUS or MRI to evaluate the tumor size, invasion depth and extent, and the involvement of pararectal lymph nodes. In total 280 patients (86.2%) were evaluated by ERUS and 45 patients (13.8%) by MRI. Serum CEA was measured and abdominal CT and chest radiography were also routinely performed before treatment.

We adopted neoadjuvant radiation with a total dose of 30 Gy (30 Gy/10 fractions), recommended by the Chinese Anti-Cancer Association (CACA)[11], based on some high-level clinical evidence[1213]. Surgery was performed 2-3 weeks after full dose radiation.

All included patients underwent radical resection strictly according to the principles of TME[14], regardless of abdominoperineal resection (APR) or low anterior resection (LAR). In addition, 11 patients underwent combined resection (CR) involving partial or total resections of some pelvic organs; all resection margins were identified as negative by pathologic examination.

All slides of postoperative specimens were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and were reviewed by one senior pathologist who was blind to the prognosis of patients. The available criteria for the histologic diagnosis of LVI included[15]: presence of tumor cells within lymphatic or vascular space; identification of endothelial cells lining the space; the presence of an elastic lamina surrounding the tumor; and attachment of tumor cells to the vascular wall.

Tumor regression was mostly in the form of fibro-inflammatory changes or necrosis replacing neoplastic glands. Mucin pools were also seen sometimes, as another type of degeneration post radiotherapy. Comparison between the pathologic T stage and clinical T stage (by imaging) was made to identify tumor-downstaging in the PRT group[16].

All patients in the PRT group were given postoperative chemotherapy for 6-8 cycles, using the standard regimens based on 5-FU or capecitabine, such as FOLFOX, CapeOX or capecitabine alone. In the control group, only patients with lymph node involvement or with the pathologic T3 or T4 stage were given adjuvant chemotherapy, with the same regimens as were used in the PRT group. Notably, 95% (76/80) of LVI positive patients underwent postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy, while only 4/58 LVI positive patients in the control group were not given postoperative chemotherapy due to the early TNM stage. Therefore, our results concerning prognosis involved the influence of postoperative chemotherapy.

For the patients with disease progression, three patients with resectable liver metastasis underwent partial liver resection and one patient with solitary lung metastasis underwent lung wedge resection. Two patients with resectable local recurrence underwent APR. Other patients with disease progression underwent systematic chemotherapy or support therapy.

Patients were followed at 3 mo intervals for the first two years and then at 6 mo intervals for the next three years. Evaluations consisted of physical examination, serum CEA, a complete blood count, and blood chemical analysis. Proctoscopy, abdominal ultrasonography, CT of the abdomen and pelvis, and chest radiography were also routinely used every 6-12 mo, according to the NCCN guideline[9]. Follow up time ranged from 3 to 96 mo, and the median follow up time was 72 mo. We chose 5 years as a time terminal for evaluation of outcomes. The follow up rate was 86.5% (281/325), with 44 inconclusive patients.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0 statistical software. The categorical variables were analyzed with the Pearson chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. The Kaplan-Meier survival curve was used to estimate the proportion of patients surviving or remaining disease-free at each time interval. Disease free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) curves were compared between groups using the Wilcoxon’s test for time-to-event parameters. Disease-free periods were compared using a log-rank test. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression was used to analyze the major factors affecting overall survival. All statistical tests were 2-sided, and the level of significance set at 5%.

The overall positive rate of LVI was 24.6% (80/325), with no statistically significant difference in distribution between the PRT and control groups (21.4% and 26.1% respectively, P = 0.353) (Table 1). Within the PRT group, LVI was not significantly reduced in patients with tumor-downstaging (Table 2). In the control group, LVI strongly correlated with histological differentiation and pathologic T and N stages whereas these associations were not observed in the PRT group (Table 2).

| LVI | Positive rate (%) | P value | |||

| Present | Absent | ||||

| PRT | |||||

| ypT | T1 | 1 | 5 | 16.7 | 0.592 |

| T2 | 6 | 31 | 16.2 | ||

| T3 | 14 | 44 | 24.1 | ||

| T4 | 1 | 1 | 50.0 | ||

| ypN | N0 | 9 | 54 | 14.3 | 0.057 |

| N1 | 9 | 15 | 37.5 | ||

| N2 | 4 | 12 | 25.0 | ||

| Histological differentiation | High | 1 | 3 | 25.0 | 0.998 |

| Moderate | 15 | 55 | 21.4 | ||

| Poor | 5 | 19 | 20.8 | ||

| Mucinous and signet | 1 | 4 | 21.0 | ||

| Downstaging | Yes | 7 | 34 | 17.1 | 0.388 |

| No | 15 | 47 | 24.2 | ||

| Control | |||||

| pT | T1 | 0 | 11 | 0 | < 0.01 |

| T2 | 8 | 50 | 13.8 | ||

| T3 | 49 | 98 | 33.3 | ||

| T4 | 1 | 5 | 16.7 | ||

| pN | N0 | 15 | 103 | 12.7 | < 0.01 |

| N1 | 15 | 37 | 28.8 | ||

| N2 | 28 | 24 | 53.8 | ||

| Histological differentiation | High | 7 | 22 | 24.1 | 0.015 |

| Moderate | 34 | 122 | 21.8 | ||

| Poor | 11 | 16 | 40.7 | ||

| Mucinous and signet | 6 | 4 | 60.0 | ||

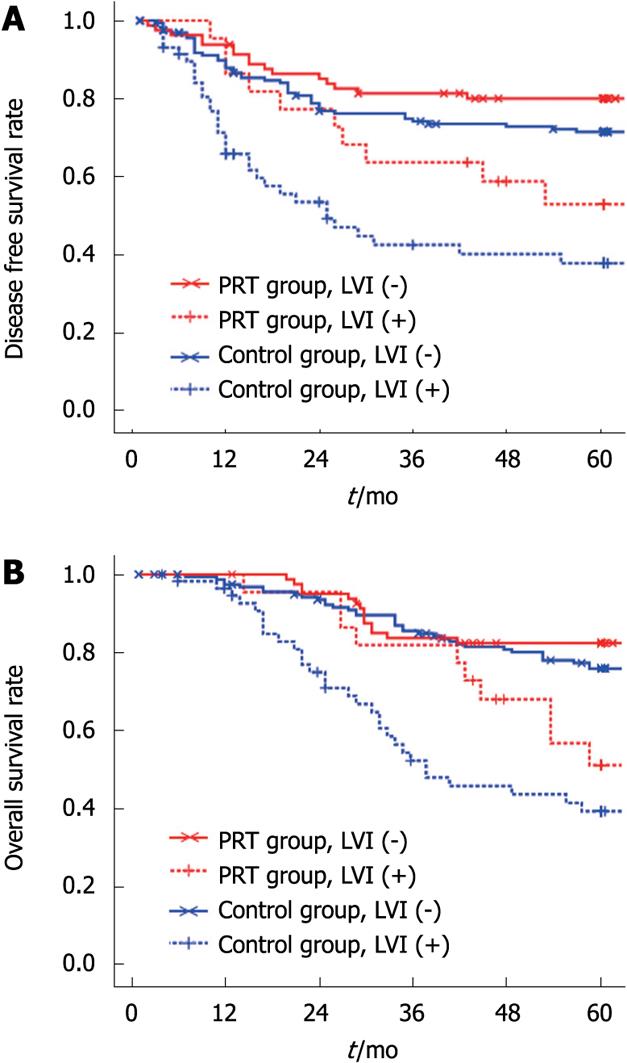

To get credible statistical results, we merged the local recurrence and distant metastasis to disease progression data because of the limited number of local recurrences in the PRT group. LVI was significantly associated with disease progression in both groups (Table 3): 38.5%-43.2% of LVI positive patients developed recurrence or metastasis, whereas 15.6%-17.6% of LVI negative patients progressed finally (P < 0.05). LVI was also strongly correlated with DFS and OS: patients with LVI had lower rates of 5 year DFS and OS in both groups (Table 3, Figure 1A and B).

| PRT | P | Control | P | ||||

| Present | Absent | Present | Absent | ||||

| Disease progression (%) | Yes | 10 (38.5) | 16 (61.5) | 0.014 | 32 (43.2) | 42 (56.8) | < 0.01 |

| No | 12 (15.6) | 65 (84.4) | 26 (17.6) | 122 (82.4) | |||

| 5-year DFS rate | % | 54.5 (12/22) | 80.2 (65/81) | 0.020 | 44.8 (26/58) | 73.2 (120/164) | < 0.01 |

| 5-year OS rate | % | 54.5 (12/22) | 82.7 (67/81) | < 0.010 | 48.3 (28/58) | 78.0 (128/164) | < 0.01 |

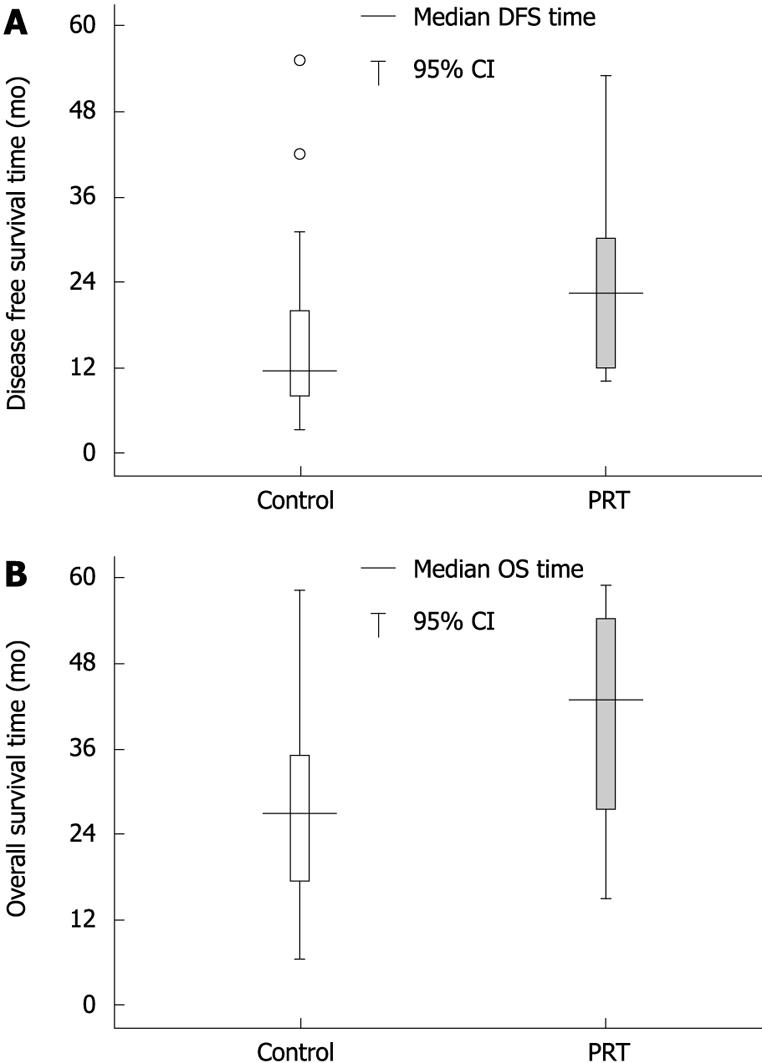

However, the influence of LVI on prognosis was not same in the two groups (Figure 2A and B). Among the patients with disease progression, LVI positive patients in the PRT group had a longer disease-free period and survival time than those in the control group (the median DFS time was 22.5 and 11.5 mo respectively, P = 0.023; the median OS time was 42.5 and 26.5 mo respectively, P = 0.035). There were no statistically significant differences in the 5 year DFS rate (54.4% vs 44.8%, P = 0.099) and OS rate (54.4% vs 48.3%, P = 0.137). For LVI negative patients, neither DFS nor OS showed significant differences between the two groups (the median DFS time was 14.0 and 15.0 mo respectively, P = 0.980; the median OS time was 29.8 and 34.0 mo respectively, P = 0.247).

Multivariate analysis demonstrated that the distance of the tumor from the anal verge, pretreatment serum CEA level, pathologic TNM stage and LVI were the major factors affecting the 5 year OS (Table 4) whereas gender, age, neoadjuvant radiotherapy, tumor-downstaging, histological differentiation and pretreatment stage were not significantly associated with long-term survival.

| Variable | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P value |

| Distance from anal verge | 0.540 | 0.346-0.845 | < 0.01 |

| Serum CEA level | 1.334 | 1.027-1.732 | 0.031 |

| pTNM stage | 1.347 | 1.198-1.514 | < 0.01 |

| LVI | 0.450 | 0.292-0.692 | < 0.01 |

Strictly speaking, lymphovascular invasion implies involvement of vascular and lymphatic vessels. However, histological distinction between larger lymphatic and smaller venous channels may not always be possible. Therefore, the term lymphovascular is used to refer to any or all of these structures[17]. LVI could be recognized clearly on HE-stained slides, despite the fact that some reports indicate using immunohistochemical stains with CD31 and D2-40 may improve the diagnosis[1819].

LVI has long been recognized as a favorable independent pathological indicator for predicting the prognosis of patients with colorectal cancer, which is usually associated with a poor consequence[6–8]. However, most studies concerning LVI were made in patients not given neoadjuvant therapy. Although several authors mentioned in their studies that LVI correlated with awful prognosis in patients undergoing neoadjuvant therapy[2021], there have been very few studies that specifically investigated the difference in LVI after neoadjuvant therapy compared to LVI after surgery directly. Our study was undertaken to illuminate such differences.

Despite the fact that preoperative radiation may lead to some histological changes, such as tumor regression or even a complete response[32223], our study found that preoperative radiotherapy alone did not significantly reduce the occurrence of LVI: at the same pathologic stage, the positive rates of LVI in the two groups were not significantly different (21.4% vs 26.1%, P = 0.353). Even for patients with tumor-downstaging, who could be considered sensitive to radiation, the LVI positive rate was not significantly reduced which implied the killing effect of X-rays to cancer cells involved in the vessels may be limited. Perhaps the addition of concurrent chemotherapy may work on LVI more effectively, which will be our continuing work based on the results from the current study. However, the influence of radiochemotherapy on LVI is more complicated, so we chose radiotherapy alone as the first step.

However, the behavior of tumor cells involved in the vessels somewhat changed after radiation. Our results demonstrated that the disease progression of patients with LVI in the PRT group was significantly delayed, which suggested that the aggression of those tumor cells in the blood or lymphatic vessels may have been significantly weakened by X-ray, though they were not completely eliminated. Currently, it is generally believed that radiation can cause DNA damage and chromosome aberrations, leading to an abortion of cell mitosis and proliferation, as well as inducing cell apoptosis[2425]. Therefore, we inferred that the tumor cells involved in the vessels may be partly killed or inhibited by neoadjuvant radiotherapy so that disease progression was delayed and the survival time was prolonged.

At present, the issue about who would benefit from neoadjuvant therapy is still being debated. Some authors believe that only patients with a good response to radiation could benefit from neoadjuvant therapy[3162627]. Our study demonstrated patients with LVI could gain a prolonged disease-free period and survival time from neoadjuvant radiotherapy. Thus, LVI positive patients may also benefit from neoadjuvant radiotherapy in a sense.

Currently, neoadjuvant therapy has become a standard protocol for locally advanced rectal cancer. Although some studies have demonstrated that lymphovascular invasion (LVI) after neoadjuvant therapy is a high risk factor for recurrence, there have been very few studies that specially addressed the meaning of LVI after neoadjuvant therapy. The study is designed to compare the difference in LVI between patients undergoing neoadjuvant radiotherapy and those undergoing surgery directly.

The pathologic evaluation of the rectal cancer after neoadjuvant therapy is the hotspot most oncologists and scholars focus on.

The study specifically addresses the meaning of LVI in rectal cancer after neoadjuvant radiotherapy; furthermore, they are first to report the difference in LVI after neoadjuvant radiotherapy.

They demonstrated that patients with LVI could gain a prolonged disease-free period and survival time from neoadjuvant radiotherapy which provides significant evidence and reference for the application of neoadjuvant radiotherapy.

Lymphovascular invasion: a morphological concept which refers to the presence of tumor cells within lymphatic or vascular vessels, representing strong aggression of tumor cells.

The manuscript, reported by Du et al, investigates, in a retrospective cohort study, the difference in LVI after neoadjuvant therapy compared to LVI after surgery directly. This manuscript is well presented and gives us an interesting result. The patient’s cohort is important.

| 1. | Lindsetmo RO, Joh YG, Delaney CP. Surgical treatment for rectal cancer: an international perspective on what the medical gastroenterologist needs to know. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3281-3289. |

| 2. | Scott NA, Susnerwala S, Gollins S, Myint AS, Levine E. Preoperative neo-adjuvant therapy for curable rectal cancer--reaching a consensus 2008. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11:245-248. |

| 3. | Jass JR, O’Brien MJ, Riddell RH, Snover DC. Recommendations for the reporting of surgically resected specimens of colorectal carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:537-545. |

| 4. | Micev M, Micev-Cosic M, Todorovic V, Krsmanovic M, Krivokapic Z, Popovic M, Barisic G, Markovic V, Jelic-Radosevic L, Popov I. Histopathology of residual rectal carcinoma following preoperative radiochemotherapy. Acta Chir Iugosl. 2004;51:99-108. |

| 5. | Bouzourene H, Bosman FT, Matter M, Coucke P. Predictive factors in locally advanced rectal cancer treated with preoperative hyperfractionated and accelerated radiotherapy. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:541-548. |

| 6. | Ross A, Rusnak C, Weinerman B, Kuechler P, Hayashi A, MacLachlan G, Frew E, Dunlop W. Recurrence and survival after surgical management of rectal cancer. Am J Surg. 1999;177:392-395. |

| 7. | Koukourakis MI, Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, Gatter KC, Harris AL. Inclusion of vasculature-related variables in the Dukes staging system of colon cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:8653-8660. |

| 8. | Compton CC, Fielding LP, Burgart LJ, Conley B, Cooper HS, Hamilton SR, Hammond ME, Henson DE, Hutter RV, Nagle RB. Prognostic factors in colorectal cancer. College of American Pathologists Consensus Statement 1999. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:979-994. |

| 9. | National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: colon cancer. : Washington 2008; COL-3. |

| 10. | National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: colon cancer. : Washington 2008; REC-7. |

| 11. | The Committee of Colorectal Cancer of the Chinese Anti-Cancer Association. The surgical guideline of low rectal cancer. Chin J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;88-90. |

| 12. | Camma C, Giunta M, Fiorica F, Pagliaro L, Craxe A, Cottone M. Preoperative radiotherapy for resectable rectal cancer: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2000;284:1008-1015. |

| 13. | Figueredo A, Zuraw L, Wong RK, Agboola O, Rumble RB, Tandan V. The use of preoperative radiotherapy in the management of patients with clinically resectable rectal cancer: a practice guideline. BMC Med. 2003;1:1. |

| 14. | Heald RJ, Karanjia ND. Results of radical surgery for rectal cancer. World J Surg. 1992;16:848-857. |

| 15. | Harris EI, Lewin DN, Wang HL, Lauwers GY, Srivastava A, Shyr Y, Shakhtour B, Revetta F, Washington MK. Lymphovascular invasion in colorectal cancer: an interobserver variability study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:1816-1821. |

| 16. | Theodoropoulos G, Wise WE, Padmanabhan A, Kerner BA, Taylor CW, Aguilar PS, Khanduja KS. T-level downstaging and complete pathologic response after preoperative chemoradiation for advanced rectal cancer result in decreased recurrence and improved disease-free survival. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:895-903. |

| 17. | Hoda SA, Hoda RS, Merlin S, Shamonki J, Rivera M. Issues relating to lymphovascular invasion in breast carcinoma. Adv Anat Pathol. 2006;13:308-315. |

| 18. | Walgenbach-Bruenagel G, Tolba RH, Varnai AD, Bollmann M, Hirner A, Walgenbach KJ. Detection of lymphatic invasion in early stage primary colorectal cancer with the monoclonal antibody D2-40. Eur Surg Res. 2006;38:438-444. |

| 19. | Kingston EF, Goulding H, Bateman AC. Vascular invasion is underrecognized in colorectal cancer using conventional hematoxylin and eosin staining. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1867-1872. |

| 20. | Guillem JG, Chessin DB, Cohen AM, Shia J, Mazumdar M, Enker W, Paty PB, Weiser MR, Klimstra D, Saltz L. Long-term oncologic outcome following preoperative combined modality therapy and total mesorectal excision of locally advanced rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2005;241:829-836; discussion 836-838. |

| 21. | Stewart D, Yan Y, Mutch M, Kodner I, Hunt S, Lowney J, Birnbaum E, Read T, Fleshman J, Dietz D. Predictors of disease-free survival in rectal cancer patients undergoing curative proctectomy. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:879-886. |

| 22. | Graf W, Dahlberg M, Osman MM, Holmberg L, Pahlman L, Glimelius B. Short-term preoperative radiotherapy results in down-staging of rectal cancer: a study of 1316 patients. Radiother Oncol. 1997;43:133-137. |

| 23. | Janjan NA, Khoo VS, Abbruzzese J, Pazdur R, Dubrow R, Cleary KR, Allen PK, Lynch PM, Glober G, Wolff R. Tumor downstaging and sphincter preservation with preoperative chemoradiation in locally advanced rectal cancer: the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;44:1027-1038. |

| 24. | Cui Y, Yang H, Wu S, Gao L, Gao Y, Peng R, Cui X, Xiong C, Hu W, Wang D. Molecular mechanism of damage and repair of mouse thymus lymphocytes induced by radiation. Chin Med J (Engl). 2002;115:1070-1073. |

| 25. | Lipfert J, Llano J, Eriksson LA. Radiation-induced damage in serine phosphate-insights into a mechanism for direct DNA strand breakage. J Phys Chem B. 2004;108:8036-8042. |

| 26. | Collette L, Bosset JF, den Dulk M, Nguyen F, Mineur L, Maingon P, Radosevic-Jelic L, Pierart M, Calais G. Patients with curative resection of cT3-4 rectal cancer after preoperative radiotherapy or radiochemotherapy: does anybody benefit from adjuvant fluorouracil-based chemotherapy? A trial of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Radiation Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4379-4386. |

| 27. | Sebag-Montefiore D, Stephens RJ, Steele R, Monson J, Grieve R, Khanna S, Quirke P, Couture J, de Metz C, Myint AS. Preoperative radiotherapy versus selective postoperative chemoradiotherapy in patients with rectal cancer (MRC CR07 and NCIC-CTG C016): a multicentre, randomised trial. Lancet. 2009;373:811-820. |