Published online Jul 21, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3376

Revised: June 13, 2009

Accepted: June 20, 2009

Published online: July 21, 2009

AIM: To evaluate the ultrasonography (EUS) features of gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) as compared with gastric leiomyomas and then to determine the EUS features that could predict malignant GISTs.

METHODS: We evaluated the endoscopic EUS features in 53 patients with gastric mesenchymal tumors confirmed by histopathologic diagnosis. The GISTs were classified into benign and malignant groups according to the histological risk classification.

RESULTS: Immunohistochemical analyses demonstrated 7 leiomyomas and 46 GISTs. Inhomogenicity, hyperechogenic spots, a marginal halo and higher echogenicity as compared with the surrounding muscle layer appeared more frequently in the GISTs than in the leiomyomas (P < 0.05). The presence of at least two of these four features had a sensitivity of 89.1% and a specificity of 85.7% for predicting GISTs. Except for tumor size and irregularity of the border, most of the EUS features were not helpful for predicting the malignant potential of GISTs. On multivariate analysis, only the maximal diameter of the GISTs was an independent predictor. The optimal size for predicting malignant GISTs was 35 mm. The sensitivity and specificity using this value were 92.3% and 78.8%, respectively.

CONCLUSION: EUS may help to differentiate gastric GISTs from gastric leiomyomas. Once GISTs are suspected, surgery should be considered if the size is greater than 3.5 cm.

- Citation: Kim GH, Park DY, Kim S, Kim DH, Kim DH, Choi CW, Heo J, Song GA. Is it possible to differentiate gastric GISTs from gastric leiomyomas by EUS? World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(27): 3376-3381

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i27/3376.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.3376

Mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract are usually incidentally discovered as a firm, protruding submucosal lesion during upper gastrointestinal examinations for unrelated conditions, although the larger tumors may occasionally cause bleeding[1]. Pathologically, most of these tumors are composed of spindle cells and display smooth muscle differentiation. In recent years, with the advance of immunohistochemistry, it is known that most gastric and small bowel mesenchymal tumors are gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) that are derived from the interstitial cells of Cajal[1–3]. The incidence of GISTs is 10-20 per million with the stomach being the most common location as 60% to 70% of GISTs arise in this organ[4].

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) is a valuable imaging tool for the diagnosis and evaluation of gastric GISTs. Gastric GISTs generally appear as round, hypoechoic lesions with a ground-glass echo texture, and these lesions are contiguous with the fourth layer of the stomach[5–7]. Several studies have attempted to differentiate benign and malignant stromal tumors on the basis of their EUS features[6–11]. However, most of these studies were performed before the concept of GISTs was introduced and they included non-gastric tumors in their study samples. In addition, little is known about differentiating GISTs and leiomyomas by EUS[11].

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the EUS features of gastric GISTs in comparison with gastric leiomyomas, and we wanted to determine if the EUS features could predict the malignant potential of gastric GISTs according to the histological risk classification.

From July 2005 to June 2008, the medical records of all patients with histopathologically proven gastric leiomyomas or GISTs who underwent EUS examination at our endoscopic unit were retrospectively reviewed. There were 53 patients (22 men and 31 women), with a mean age of 59 years (range 29-75 years). The histologic specimens were obtained by surgical resection in 50 patients (94.3%), by needle biopsy in two patients (3.8%), and by endoscopic resection in 1 patient (1.9%). This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at Pusan National University Hospital.

The tumors were histopathologically proved to be gastric mesenchymal tumors and they were classified immunohistochemically as leiomyomas or GISTs[3]. In particular, the leiomyomas were defined as being desmin positive and c-kit (CD117) negative tumors and the GISTs were defined as being c-kit positive tumors. The GISTs were divided into 4 groups in accordance with the consensus meeting report at the National Institute of Health (Table 1)[12]. Then, the GISTs with a very low risk or low risk were defined as benign GISTs, and the GISTs with an intermediate risk or high risk were defined as malignant GISTs.

| Size (cm) | Mitotic count | |

| Very low risk | < 2 | < 5/50 HPF |

| Low risk | 2-5 | < 5/50 HPF |

| Intermediate risk | < 5 | 6-10/50 HPF |

| 5-10 | < 5/50 HPF | |

| High risk | > 5 | > 5/50 HPF |

| > 10 | Any mitotic rate | |

| Any size | > 10/50 HPF |

EUS was performed with a radial scanning ultrasound endoscope (GF-UM2000; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) using scanning frequencies of 7.5 and 12 MHz. All the examinations were performed under intravenous conscious sedation (midazolam with or without meperidine). Scanning of the tumor was performed after filling the stomach with 400-600 mL of deaerated water. About 10-20 endosonograms were recorded for each patient, and these images were stored on magneto-optical disks. A review of the EUS photos was performed by a single experienced endosonographer (Kim GH) who was kept “blinded” to the final diagnosis, and this endosonography had previously performed more than 1000 examinations. The following EUS features were recorded for all the tumors: (a) the maximal diameter, (b) the presence of mucosal ulceration on endoscopy and/or EUS, (c) the echogenicity in comparison with the surrounding normal proper muscle layer (hyperechoic or isoechoic), (d) the homogeneity (homogenous or heterogenous), (e) the presence of a marginal halo and lobulation, (f) the presence of cystic spaces, hyperechogenic spots and calcification, (g) the regularity of the marginal border (regular or irregular) and (h) the pattern of tumor growth (inside or outside the gastric wall).

The differences in gender and the EUS findings between leiomyomas and GISTs were assessed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, and the patient age and tumor size were assessed using the Student t-test. Calculation of the sensitivity, specificity and the positive and negative predictive values of each EUS feature and combinations of these features for differentiating GISTs from leiomyomas were carried out manually.

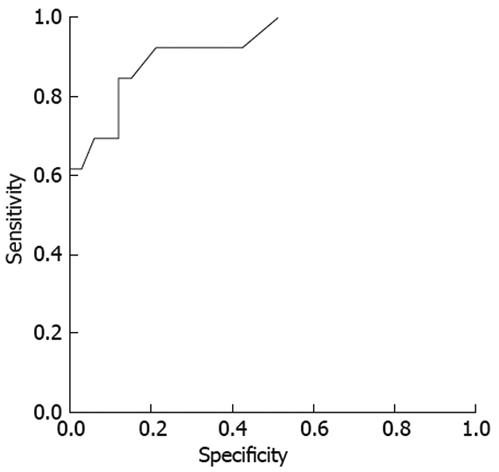

Univariate analyses using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test were performed to identify the EUS features that could predict malignant GISTs. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify the independent predictors of malignant GISTs. The odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals were used to predict malignant GISTs. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was applied to find the best sensitivity and specificity cut-off value of the tumor size for predicting malignant GISTs. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical calculations were performed using the SPSS version 12.0 for Windows software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

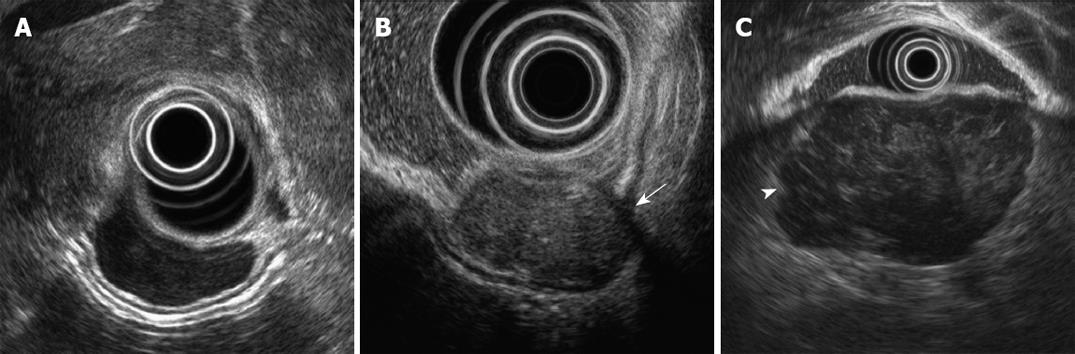

Immunohistochemical analyses demonstrated that 7 cases were leiomyomas and 46 cases were GISTs. The baseline characteristics and endosonographic features are shown in Table 2. The tumor size and presence of ulceration were not different between the leiomyomas and the GISTs. A marginal halo appeared more frequently in the GISTs than in the leiomyomas (P = 0.002). The echogenicity of all the leiomyomas was nearly similar to that of the surrounding normal proper muscle layer, but more than half of the GISTs showed higher echogenicity than that of the surrounding normal muscle layer (Figure 1) (P = 0.004). Inhomogeneity of the tumor and hyperechogenic spots were observed more frequently in the GISTs than in the leiomyomas (P < 0.05).

| Variables | Leiomyomas (n = 7) | GISTs (n = 46) | P-value |

| Gender | 0.686 | ||

| Male | 2 (28.6) | 20 (43.5) | |

| Female | 5 (71.4) | 26 (56.5) | |

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 52.6 ± 13.5 | 57.5 ± 8.4 | 0.193 |

| Location | 0.272 | ||

| Upper | 6 (85.7) | 29 (63.0) | |

| Middle | 0 (0) | 13 (28.3) | |

| Lower | 1 (14.3) | 4 (8.7) | |

| Originating layer | 0.644 | ||

| Second layer | 0 | 1 (2.2) | |

| Third layer | 2 (28.6) | 7 (15.2) | |

| Fourth layer | 5 (71.4) | 38 (82.6) | |

| Size (cm, mean ± SD) | 3.6 ± 2.6 | 3.5 ± 2.3 | 0.967 |

| Ulcer | 0.172 | ||

| Absent | 7 (100) | 31 (67.4) | |

| Present | 0 (0) | 15 (32.6) | |

| Growth | 0.660 | ||

| In | 6 (85.7) | 33 (71.7) | |

| Out | 1 (14.3) | 13 (28.3) | |

| Border | 0.082 | ||

| Regular | 7 (100) | 29 (63.0) | |

| Irregular | 0 (0) | 17 (37.0) | |

| Lobulation | 0.426 | ||

| Absent | 5 (71.4) | 23 (50.0) | |

| Present | 2 (28.6) | 23 (50.0) | |

| Marginal halo | 0.002 | ||

| Absent | 6 (85.7) | 10 (21.7) | |

| Present | 1 (14.3) | 36 (78.3) | |

| Echogenicity in comparison with the surrounding muscle echo | 0.004 | ||

| Isoechoic | 7 (100) | 19 (41.3) | |

| Hyperechoic | 0 (0) | 27 (58.7) | |

| Homogeneity | 0.001 | ||

| Homogenous | 6 (85.7) | 9 (19.6) | |

| Inhomogenous | 1 (14.3) | 37 (80.4) | |

| Cystic change | 0.661 | ||

| Absent | 6 (85.7) | 31 (67.4) | |

| Present | 1 (14.3) | 15 (32.6) | |

| Hyperechogenic spots | 0.012 | ||

| Absent | 4 (57.1) | 5 (10.9) | |

| Present | 3 (42.9) | 41 (89.1) | |

| Calcification | 1.000 | ||

| Absent | 6 (85.7) | 39 (84.8) | |

| Present | 1 (14.3) | 7 (15.2) | |

Table 3 shows the value of each EUS feature for differentiating GISTs from leiomyomas. Each criterion had a high positive predictive value, but limited sensitivity or specificity. The presence of at least two of these four features in a given tumor had a sensitivity of 89.1%, a specificity of 85.7%, a positive predictive value of 97.6% and a negative predictive value of 54.5% for predicting GISTs.

| EUS features | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive predictive value | Negative predictive value |

| Echogenicity in comparison with the surrounding muscle echo | 58.7 | 100 | 100 | 26.9 |

| Homogeneity | 80.4 | 85.7 | 97.4 | 40.0 |

| Echogenic foci | 89.1 | 57.1 | 93.2 | 44.4 |

| Marginal halo | 78.3 | 85.7 | 97.3 | 37.5 |

| Of the above 4 features | ||||

| ≥ 1 | 97.8 | 57.1 | 93.8 | 80.0 |

| ≥ 2 | 89.1 | 85.7 | 97.6 | 54.5 |

| ≥ 3 | 84.8 | 85.7 | 97.5 | 46.2 |

| All | 34.8 | 100 | 100 | 18.9 |

When the GISTs were classified into benign and malignant groups according to the histological risk classification, 33 cases were grouped as benign GISTs (very low risk, 11 cases; low risk, 22 cases) and 13 cases as malignant GISTs (intermediate risk, 8 cases; high risk, 5 cases). Except for the size and irregularity of the tumor border, most of the endosonographic features were not helpful in predicting the malignant potential of GISTs (Figure 1, Table 4). On the multivariate logistic regression analysis, only the maximal diameter of the GISTs was an independent predictor (OR, 9.3; 95% CI, 1.6-53.6) (Table 5). A ROC curve was created to identify the discriminative value of size for predicting the malignant potential of GISTs (Figure 2). The sensitivity was almost optimized when the critical value of the size was 35 mm. Of the 19 patients with a tumor size ≥ 35 mm, 12/19 (63.2%) were malignant GISTs. However, of the 27 patients with a size < 35 mm, 26 (96.3%) were benign GISTs and 1 (3.7%) was a malignant GIST. Therefore, this model of prediction for malignant GISTs had a positive predictive value of 63.2% and a negative predictive value of 96.3%. This resulted in a sensitivity of 92.3% and a specificity of 78.8%.

| Variables | Benign GIST (n = 33) | Malignant GIST (n = 13) | P-value |

| Size (cm, mean ± SD) | 2.5 ± 1.0 | 6.0 ± 2.7 | 0.001 |

| Ulcer | 0.299 | ||

| Absent | 24 (72.7) | 7 (53.8) | |

| Present | 9 (27.3) | 6 (46.2) | |

| Growth | 0.145 | ||

| In | 26 (78.8) | 7 (53.8) | |

| Out | 7 (21.2) | 6 (46.2) | |

| Border | 0.044 | ||

| Regular | 24 (72.7) | 5 (38.5) | |

| Irregular | 9 (27.3) | 8 (61.5) | |

| Lobulation | 0.743 | ||

| Absent | 17 (51.5) | 6 (46.2) | |

| Present | 16 (48.5) | 7 (53.8) | |

| Marginal halo | 0.240 | ||

| Absent | 9 (27.3) | 1 (7.7) | |

| Present | 24 (72.7) | 12 (92.3) | |

| Echogenicity in comparison with the surrounding muscle echo | 0.115 | ||

| Isoechoic | 16 (48.5) | 3 (23.1) | |

| Hyperechoic | 17 (51.5) | 10 (76.9) | |

| Homogeneity | 0.199 | ||

| Homogenous | 8 (24.2) | 1 (7.7) | |

| Inhomogenous | 25 (75.8) | 12 (92.3) | |

| Cystic changes | 0.082 | ||

| Absent | 25 (75.8) | 6 (46.2) | |

| Present | 8 (24.2) | 7 (53.8) | |

| Hyperechogenic spots | 1.000 | ||

| Absent | 4 (12.1) | 1 (7.7) | |

| Present | 29 (87.9) | 12 (92.3) | |

| Calcification | 0.385 | ||

| Absent | 29 (87.9) | 10 (76.9) | |

| Present | 4 (12.1) | 3 (23.1) | |

| Variables | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value |

| Size | 9.3 (1.6-53.6) | 0.013 |

| Growth | 8.7 (0.6-119.8) | 0.105 |

| Border | 2.3 (0.2-22.7) | 0.490 |

| Homogenicity | 2.2 (0.1-48.0) | 0.606 |

| Cystic change | 1.4 (0.1-19.5) | 0.800 |

GISTs are rare neoplasms that account for less than 1% of all gastrointestinal malignancies. GISTs have the capability to become malignant and then metastasize, whereas leiomyomas are almost invariably benign[4]. In clinical practice, preoperative differentiation between GISTs and leiomyomas is usually difficult, even if EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration or trucut biopsy is performed[13–15]. Thus, if it were possible to differentiate GISTs from leiomyomas and then to predict the malignant potential of GISTs by EUS imaging, then this would be essential in the clinical management of gastrointestinal mesenchymal tumors. There have been several studies that have attempted to differentiate benign from malignant stromal tumors based on their EUS features[25–11]. However, most of these studies did not differentiate the EUS features of GISTs and leiomyomas, and they did not characterize the EUS features of GISTs according to the histological risk classification. In addition, they did not restrict the study subjects to those with the gastric mesenchymal tumors.

Initially, we tried to find the EUS features that could differentiate GISTs from leiomyomas. In a previous study[9], the EUS features such as size greater than 4 cm, ulceration or cystic foci were almost exclusively seen in CD-117 positive tumors as compared with CD-117 negative tumors. In that study, immunohistochemical staining such as for desmin or S-100 was not performed, so the CD-117 negative tumors were not homogenous; i.e. they may have been leiomyomas or schwannomas. In the present study, we restricted the subjects to compare GISTs with only leiomyomas, and the latter are almost invariably benign. As a result, tumor size and the presence of ulceration and cystic changes in the tumor were not helpful for differentiating GISTs from leiomyomas in this study. Instead, inhomogenicity, hyperechogenic spots, a marginal halo and higher echogenicity in comparison with the surrounding muscle layer were helpful for predicting GISTs. Especially, if at least two of these four features are present, then the sensitivity and specificity for predicting GISTs were 89.1% and 85.7%, respectively. This result is similar to the results of a previous report[11] that a marginal halo and the relatively higher echogenicity, as compared to the adjacent normal muscular layer on EUS, might suggest GISTs. In addition, the previous reports, which were carried out before the concept of GISTs was introduced, have suggested that inhomogeneity and hyperechogenic spots are the EUS features that are predictive of malignancy[67].

A hypoechoic halo is a well known characteristic ultrasonographic sign of malignant liver tumors such as hepatocellular carcinoma[16]. A pseudocapsule of the collapsed surrounding tissues, which is the result of an expansively growing tumor, is thought to be the cause of the halo in malignant liver tumors[16]. A previous study showed that on pathologic examination, the tumor cells of GISTs were partially or completely circumscribed by the residual muscle tissues of the surrounding muscular propria and this formed a capsule-like structure[11]. In the present study, a marginal halo was found in 78.3% of GISTs, whereas this was seen in only 14.3% of leiomyomas.

In this study, higher echogenicity in comparison with the surrounding muscle layer was found in more than half of GISTs, whereas the echogenicity of the leiomyomas was nearly equal to that of the surrounding muscle layer. Pathologically, it is well known that the cellularity of leiomyomas is normal to moderate with eosinophilic cytoplasm, whereas GISTs show higher overall cellularity, which creates a basophilic appearance on hematoxylin and eosin staining[1–3]. It is assumed that the difference in echogenicity between GISTs and leiomyomas might reflect these pathologic differences of cellularity and the structural components of the tumors.

Second, we tried to find the EUS features that could predict the malignant potential of GISTs after dividing the GISTs into 2 groups (benign and malignant) according to the histological risk classification. Previous studies have suggested that a large size, exogastric growth, ulceration, cystic changes, hyperechogenic foci and irregularity of the margin favored a diagnosis of malignant gastrointestinal mesenchymal tumors[671718], but these studies were performed before the concept of GISTs had been introduced, as was mentioned earlier. In the present study, only tumor size and irregularity of the border were helpful in predicting the malignant potential of GISTs. Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that only size was an independent predictor, which is consistent with a previous report that conducted multivariate analysis according to the histological risk classification of GISTs[10]. With the critical size of 35 mm, the sensitivity and specificity were 92.3% and 78.8%, respectively. This could be explained by the fact that tumor size, together with the mitotic count, is used to determine the histological classification system. Therefore, once we discriminate GISTs from leiomyomas, the size of the tumor (> 35 mm) might be the most reliable indicator of malignancy.

This study had several limitations. First, this was a retrospective study that compared the EUS features of gastric GISTs and leiomyomas. In addition, there might have been a potential bias when retrospectively reviewing the endosonographic photos. During the EUS examination, we took at least 10-20 endosonographic photos to determine EUS characteristics of gastric mesenchymal tumors. Therefore, this would compensate, to some degree, the limitation of this retrospective study. Second, although EUS examinations were performed, patients were selected for surgery or biopsy according to the clinical opinions and decisions of the medical doctors. Third, the number of leiomyomas included in this study was small relative to the number of GISTs. This limitation might be due to the fact that the most common mesenchymal tumors of the stomach are GISTs and other tumors, such as leiomyomas and schwannomas, are rarely encountered in clinics.

Gastric mesenchymal tumors are often asymptomatic, and they are usually incidentally discovered during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy for unrelated conditions. The main problem in the asymptomatic patient is to determine whether or not the tumors have a malignant potential. Because GISTs have a malignant potential, the gastric mesenchymal tumors, even if they are small, should not be ignored if EUS features are suggestive of GISTs. Further large prospective long-term studies are needed to validate our results for gastric mesenchymal tumors.

In conclusion, EUS is a useful method to diagnose gastric mesenchymal tumors and to predict the malignant potential of GISTs. The EUS features such as inhomogeneity, hyperechogenic spots, a marginal halo and higher echogenicity as compared with the surrounding muscle layer may help to differentiate GISTs from leiomyomas. Once GISTs are suspected by EUS, surgical treatment should be considered if the size of the tumor is greater than 3.5 cm.

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) is a valuable imaging tool for the diagnosis and evaluation of gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs). Several studies have attempted to differentiate benign and malignant stromal tumors on the basis of their EUS features. However, most of these studies were performed before the concept of GISTs was introduced and they included non-gastric tumors in their study samples.

Most previous studies did not differentiate the EUS features of GISTs and leiomyomas, and they did not characterize the EUS features of GISTs according to the histological risk classification. In addition, they did not restrict the study subjects to those with gastric mesenchymal tumors. Therefore, we evaluated the EUS features of gastric GISTs in comparison with gastric leiomyomas, and tried to determine the EUS features that could predict the malignant potential of gastric GISTs according to the histological risk classification.

To differentiate GISTs from leiomyomas by EUS, the following four features were helpful; inhomogenicity, hyperechogenic spots, a marginal halo and higher echogenicity as compared with the surrounding muscle layer. These features appeared more frequently in GISTs than in leiomyomas. The presence of at least two of these four features had a sensitivity of 89.1% and a specificity of 85.7% for predicting GISTs. Except for tumor size and irregularity of the border, most of the EUS features were not helpful in predicting the malignant potential of GISTs. On multivariate analysis, only the maximal diameter of the GISTs was an independent predictor. The optimal size for predicting malignant GISTs was 35 mm. The sensitivity and specificity using this value were 92.3% and 78.8%, respectively.

EUS is a useful method to diagnose gastric mesenchymal tumors and to predict the malignant potential of GISTs. The EUS features such as inhomogeneity, hyperechogenic spots, a marginal halo and higher echogenicity as compared with the surrounding muscle layer may help to differentiate GISTs from leiomyomas. Once GISTs are suspected by EUS, surgical treatment should be considered if the size of the tumor is greater than 3.5 cm.

GISTs are mesenchymal tumors derived from the interstitial cells of Cajal. The incidence of GISTs is 10-20 per million and the stomach is the most common location of GISTs (60%-70%).

This is a relatively large single-center study aiming to evaluate the EUS features of gastric GISTs vs leiomyomas initially and subsequently focusing on GISTs to determine EUS-features associated with malignancy.

| 1. | Pidhorecky I, Cheney RT, Kraybill WG, Gibbs JF. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: current diagnosis, biologic behavior, and management. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:705-712. |

| 2. | Sarlomo-Rikala M, Kovatich AJ, Barusevicius A, Miettinen M. CD117: a sensitive marker for gastrointestinal stromal tumors that is more specific than CD34. Mod Pathol. 1998;11:728-734. |

| 3. | Miettinen M, Sobin LH, Sarlomo-Rikala M. Immunohistochemical spectrum of GISTs at different sites and their differential diagnosis with a reference to CD117 (KIT). Mod Pathol. 2000;13:1134-1142. |

| 4. | Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors--definition, clinical, histological, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic features and differential diagnosis. Virchows Arch. 2001;438:1-12. |

| 5. | Yasuda K, Cho E, Nakajima M, Kawai K. Diagnosis of submucosal lesions of the upper gastrointestinal tract by endoscopic ultrasonography. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:S17-S20. |

| 6. | Chak A, Canto MI, Rösch T, Dittler HJ, Hawes RH, Tio TL, Lightdale CJ, Boyce HW, Scheiman J, Carpenter SL. Endosonographic differentiation of benign and malignant stromal cell tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:468-473. |

| 7. | Palazzo L, Landi B, Cellier C, Cuillerier E, Roseau G, Barbier JP. Endosonographic features predictive of benign and malignant gastrointestinal stromal cell tumours. Gut. 2000;46:88-92. |

| 8. | Rösch T, Lorenz R, Dancygier H, von Wickert A, Classen M. Endosonographic diagnosis of submucosal upper gastrointestinal tract tumors. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;27:1-8. |

| 9. | Hunt GC, Rader AE, Faigel DO. A comparison of EUS features between CD-117 positive GI stromal tumors and CD-117 negative GI spindle cell tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:469-474. |

| 10. | Jeon SW, Park YD, Chung YJ, Cho CM, Tak WY, Kweon YO, Kim SK, Choi YH. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: endosonographic differentiation in relation to histological risk. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:2069-2075. |

| 11. | Okai T, Minamoto T, Ohtsubo K, Minato H, Kurumaya H, Oda Y, Mai M, Sawabu N. Endosonographic evaluation of c-kit-positive gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Abdom Imaging. 2003;28:301-307. |

| 12. | Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, Gorstein F, Lasota J, Longley BJ, Miettinen M, O'Leary TJ, Remotti H, Rubin BP. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A consensus approach. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:459-465. |

| 13. | Williams DB, Sahai AV, Aabakken L, Penman ID, van Velse A, Webb J, Wilson M, Hoffman BJ, Hawes RH. Endoscopic ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration biopsy: a large single centre experience. Gut. 1999;44:720-726. |

| 14. | Fritscher-Ravens A, Sriram PV, Schröder S, Topalidis T, Bohnacker S, Soehendra N. Stromal tumor as a pitfall in EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:746-749. |

| 15. | Varadarajulu S, Fraig M, Schmulewitz N, Roberts S, Wildi S, Hawes RH, Hoffman BJ, Wallace MB. Comparison of EUS-guided 19-gauge Trucut needle biopsy with EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration. Endoscopy. 2004;36:397-401. |

| 16. | Marchal GJ, Pylyser K, Tshibwabwa-Tumba EA, Verbeken EK, Oyen RH, Baert AL, Lauweryns JM. Anechoic halo in solid liver tumors: sonographic, microangiographic, and histologic correlation. Radiology. 1985;156:479-483. |

| 17. | Rösch T. Endoscopic ultrasonography in upper gastrointestinal submucosal tumors: a literature review. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1995;5:609-614. |

| 18. | Ando N, Goto H, Niwa Y, Hirooka Y, Ohmiya N, Nagasaka T, Hayakawa T. The diagnosis of GI stromal tumors with EUS-guided fine needle aspiration with immunohistochemical analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:37-43. |