Published online Jun 7, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2672

Revised: April 27, 2009

Accepted: May 4, 2009

Published online: June 7, 2009

An ileal perforation resulting from a migrated biliary stent is a rare complication of endoscopic stent placement for benign or malignant biliary tract disease. We describe the case of a 59-year-old woman with a history of abdominal surgery in which a migrated biliary stent resulted in an ileal perforation. Patients with comorbid abdominal pathologies, including colonic diverticuli, parastomal hernia, or abdominal hernia, may be at increased risk of perforation from migrated stents.

- Citation: Akbulut S, Cakabay B, Ozmen CA, Sezgin A, Sevinc MM. An unusual cause of ileal perforation: Report of a case and literature review. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(21): 2672-2674

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i21/2672.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.2672

The endoscopic placement of biliary stents for benign and malignant biliary disease has been performed for well over a decade and was first described in 1980 by Soehendra and Reynders-Frederix[12]. In approximately 5%-10% of cases, the procedure itself involves potential adverse side effects, such as pancreatitis, hemorrhage, perforation, and cholangitis. Long-term complications of biliary stents, such as migration and perforation, are unusual[2]. Patients with comorbid abdominal pathologies, including colonic diverticuli, parastomal hernia, or abdominal hernia, may be at increased risk of perforation from migrated stents. The available biliary endoprostheses can be classified by material into two categories: plastic and metallic stents. Plastic stents are less expensive and easier to remove or change, but have a higher risk of clogging and dislocation[34].

Generally, to prevent migration or clogging in patients with a plastic stent, the stent must be changed or removed in 3-6 mo[5]. Moreover, to avoid stent migration, the biliary stent should be placed across the sphincter of Oddi[6].

A 59-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with increasing abdominal pain. Her abdomen was tense and painful, with diffuse abdominal rebound tenderness and hyperactive bowel sounds. An upright abdominal radiograph showed minimally dilated small bowel loops and no free intraperitoneal gas. Laboratory examination gave the following results: hematocrit 30%, white blood cell count 14 500/cm3, platelets 268 000/cm3, sodium 138 mEq/L, potassium 4.6 mEq/L, blood urea nitrogen 32 mg/dL, creatinine 1.6 mg/dL, glucose 110 mg/dL, amylase 78 IU/L, total bilirubin 2.5 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase 87 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase 79 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase 550 IU/L, and γ glutamyl transferase 66 U/L.

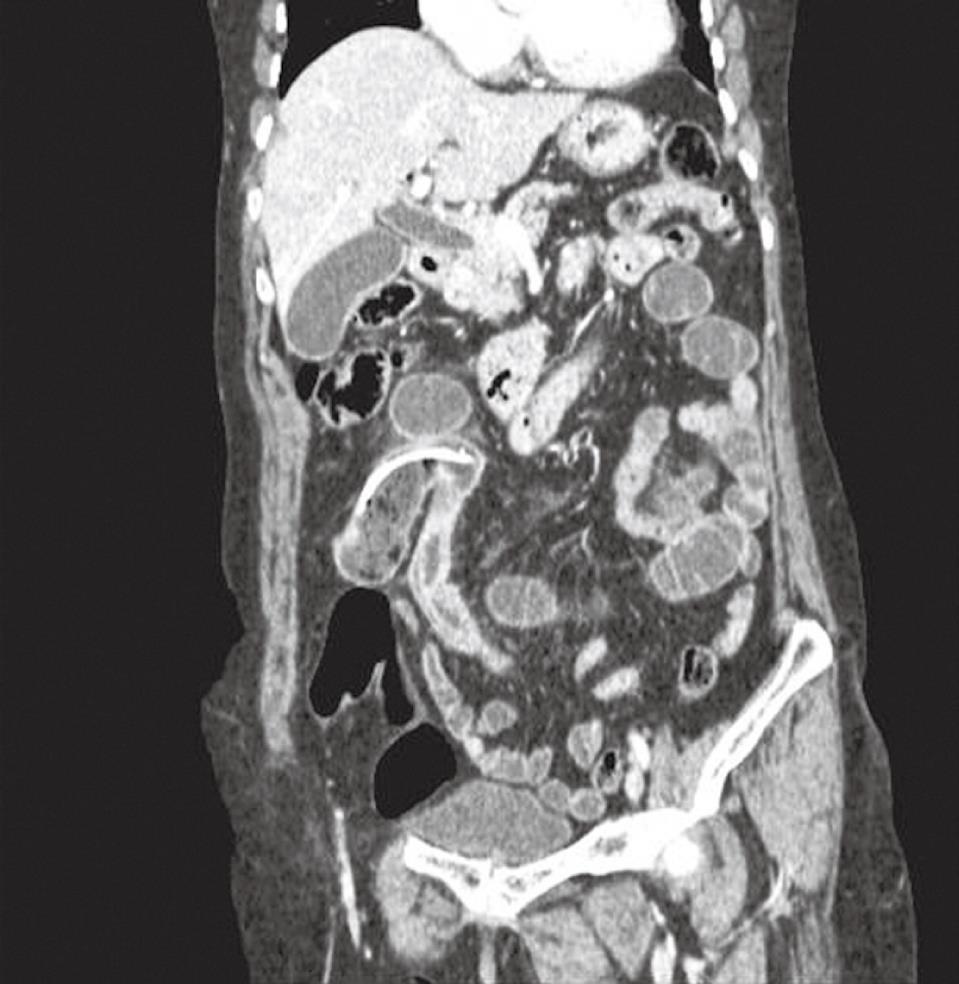

An abdominal ultrasound showed features consistent with acute cholecystitis and a dilated common duct with a diameter of 14 mm. Computed tomography (CT) was performed because of the extensive pain. Dislocation and migration of a biliary stent to the distal ileal segment was detected. CT was suspicious for an ileal perforation and the wall of the ileum was markedly thickened, with choledocholithiasis and dilated common duct with a diameter of 14 mm (Figure 1). The patient’s history included endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) 21 d before admission for an impacted stone in the common bile duct. A sphincterotomy was performed and a plastic 7-cm 11 Fr stent was placed. The patient had also undergone a laparotomy for appendicitis 20 years earlier, and three repairs of incisional hernias, 3, 4 and 6 years previously.

At laparotomy, we found multiple adhesions, dilated proximal jejunal segments, and a large amount of small intestine conglomerated in the right lower quadrant. The biliary catheter had perforated the antimesenteric surface of the distal ileum, which resulted in a protruding plastic biliary stent (Figure 2), however, the contamination was moderate because of the dense intra-abdominal adhesions. Two liters of turbid fluid were aspirated. The biliary stent was removed; the small bowel, including the perforated region, was partially resected. The patient was discharged on the seventh postoperative day, with no complications.

Occlusion is the most common problem associated with endoscopically placed stents (54%); this can be caused by tumor overgrowth or clogging by “biliary sludge,” with resulting cholangitis or recurrent obstructive jaundice[1]. Dislocation and migration of biliary stents proximally and distally in the gut is less common, occurring in less than 10% of cases, and generally causes no major problems, with the stent usually passing in the feces or remaining in the bowel with no overt symptoms. Migration is much more common with plastic stents than with metallic stents[17].

In a series of 322 endoscopically placed biliary stents, Johanson et al[8] reported proximal and distal stent migration in 4.9% and 5.9% of the patients, respectively. Intestinal perforation is an exceedingly rare complication after placement of a biliary stent. Intestinal perforation can occur during the initial insertion or endoscopic or percutaneous manipulation, or as a late consequence of biliary stent placement. In the recent literature, most (92%) cases of intestinal perforation were in the duodenum after endoscopic or percutaneous placement of a biliary stent[45910]. Various mechanisms have been postulated for duodenal perforation by biliary stents. Firstly, the stent may be placed incorrectly at the time of the procedure, and the mechanical force exerted by the tip of the plastic stent against the duodenal mucosa can lead to necrosis of the wall over time. Secondly, inflexibility or a stent of an incorrect length may lead to pressure necrosis[19].

The insertion of several smaller-diameter stents (10 Fr) rather than a single large stent (11.5 or 12 Fr) may prevent proximal stent migration. The insertion of longer rather than shorter (< 7 cm) stents may also prevent such migration. Distal perforations are less common than duodenal perforations. Reported cases involve perforation due to biliary stent migration; this is more unusual in the distal ileum and generally the cause is other diseases, such as colonic diverticuli, parastomal hernia, incarcerated hernia, and colovesicular fistulas[1810]. In our case, many adhesions resulting from the previous surgery were observed and the ileal segments were conglomerated in the right lower quadrant. These adhesions reduced the mobility of the ileum and the stent was caught in a distal ileal segment. Consequently, the sharp edge of the stent caused irritation and perforation on the antimesenteric side of the distal ileum. In the coronal maximum intensity projection abdominal CT reconstructions, the localization of the stent was obvious (Figure 1).

A review of the literature published to January 2007 revealed 11 cases of colonic perforation due to biliary stent migration, with the majority being straight plastic endoprostheses[3]. Five cases of small intestinal perforations due to a migrated biliary stent were reported, which involved an incisional hernia, parastomal hernia, appendiceal perforation, and two other diseases[111–14]. To our knowledge, this is the sixth case of small intestinal perforation due to a migrated biliary stent reported in PubMed. In our case, the clinical manifestations appeared 21 d after placing the stent via ERCP.

In conclusion, patients with risk factors such as diverticulosis, incisional and incarcerated hernias, and intra-abdominal adhesions require more attention.

| 1. | Akimboye F, Lloyd T, Hobson S, Garcea G. Migration of endoscopic biliary stent and small bowel perforation within an incisional hernia. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2006;16:39-40. |

| 2. | Soehendra N, Reynders-Frederix V. Palliative bile duct drainage - a new endoscopic method of introducing a transpapillary drain. Endoscopy. 1980;12:8-11. |

| 3. | Namdar T, Raffel AM, Topp SA, Namdar L, Alldinger I, Schmitt M, Knoefel WT, Eisenberger CF. Complications and treatment of migrated biliary endoprostheses: a review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5397-5399. |

| 4. | Levy MJ, Baron TH, Gostout CJ, Petersen BT, Farnell MB. Palliation of malignant extrahepatic biliary obstruction with plastic versus expandable metal stents: An evidence-based approach. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:273-285. |

| 5. | Frakes JT, Johanson JF, Stake JJ. Optimal timing for stent replacement in malignant biliary tract obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:164-167. |

| 6. | Pedersen FM, Lassen AT, Schaffalitzky de Muckadell OB. Randomized trial of stent placed above and across the sphincter of Oddi in malignant bile duct obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:574-579. |

| 7. | Binmoeller KF, Seitz U, Seifert H, Thonke F, Sikka S, Soehendra N. The Tannenbaum stent: a new plastic biliary stent without side holes. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1764-1768. |

| 8. | Johanson JF, Schmalz MJ, Geenen JE. Incidence and risk factors for biliary and pancreatic stent migration. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:341-346. |

| 9. | Klein U, Weiss F, Wittkugel O. [Migration of a biliary Tannenbaum stent with perforation of sigmoid diverticulum]. Rofo. 2001;173:1057. |

| 10. | Blake AM, Monga N, Dunn EM. Biliary stent causing colovaginal fistula: case report. JSLS. 2004;8:73-75. |

| 11. | Esterl RM Jr, St Laurent M, Bay MK, Speeg KV, Halff GA. Endoscopic biliary stent migration with small bowel perforation in a liver transplant recipient. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;24:106-110. |

| 12. | Mistry BM, Memon MA, Silverman R, Burton FR, Varma CR, Solomon H, Garvin PJ. Small bowel perforation from a migrated biliary stent. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:1043. |

| 13. | Tzovaras G, Liakou P, Makryiannis E, Paroutoglou G. Acute appendicitis due to appendiceal obstruction from a migrated biliary stent. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:195-196. |

| 14. | Levey JM. Intestinal perforation in a parastomal hernia by a migrated plastic biliary stent. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:1636-1637. |