Published online Mar 7, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1450

Revised: December 20, 2007

Published online: March 7, 2008

Chicken bone is one of the most frequent foreign bodies (FB) associated with upper esophageal perforation. Upper digestive tract penetrating FB may lead to life threatening complications and requires prompt management. We present the case of a 52-year-old man who sustained an upper esophageal perforation associated with cervical cellulitis and mediastinitis. Following CT-scan evidence of FB penetrating the esophagus, the impacted FB was successfully extracted under rigid esophagoscopy. Direct suture was required to close the esophageal perforation. Cervical and mediastinal drainage were made immediately. Naso-gastric tube decompression, broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics, and parenteral hyperalimentation were administered for 10 d postoperatively. An esophagogram at d 10 revealed no leak at the repair site, and oral alimentation was successfully reinstituted. Conclusion: Rigid endoscope management of FB esophageal penetration is a simple, safe and effective procedure. Primary esophageal repair with drainage of all affected compartments are necessary to avoid life-threatening complications.

- Citation: Righini CA, Tea BZ, Reyt E, Chahine KA. Cervical cellulitis and mediastinitis following esophageal perforation: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(9): 1450-1452

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i9/1450.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.1450

Management of ingested foreign bodies (FB) is a common clinical encounter. Complications of this pathology are dependent on patient age, nature and localization of the FB, presence of a perforation, and initial management procedures[1]. Beside the lingual tonsils, the base of tongue and the upper esophagus are the most common sites of FB impaction[2]. The most frequent ingested FBs in the upper digestive tract are chicken and fish bones, and they are the most commonly associated with pharyngo-esophageal perforation[1], cervical abscess and potentially life threatening complications[3].

A 52-year-old man, with no relevant past medical history, presented to the ENT clinic complaining of severe dysphagia, substernal pain, and fever for 3 d. Five days prior to presentation, the patients started having symptoms of mild dysphagia after chewing on a piece of chicken. One day later on, exacerbation of dysphagia prompted the patient to seek otolaryngology consultation in town. Following seemingly normal head and neck examination, the patient was reassured and discharged. On admission at the University Medical center of Grenoble, the patient had a fever of 40°C and mild shortness of breath. No abnormalities were noted on examination of the oropharynx, but the hypopharynx and larynx were swollen and there was abundant saliva in hypopharynx. The neck exam revealed bilateral anterior and lateral tenderness, inflammation and edema of the skin, and crepitation. On pulmonary auscultation, sparse rales were heard over the lower part of each hemi-thorax. Cardiac auscultation revealed a regular rhythm and normal heart sounds.

The patient had a white blood cell count of 20 × 109/L with 80% neutrophils and a C reactive protein level to 120 mg/L.

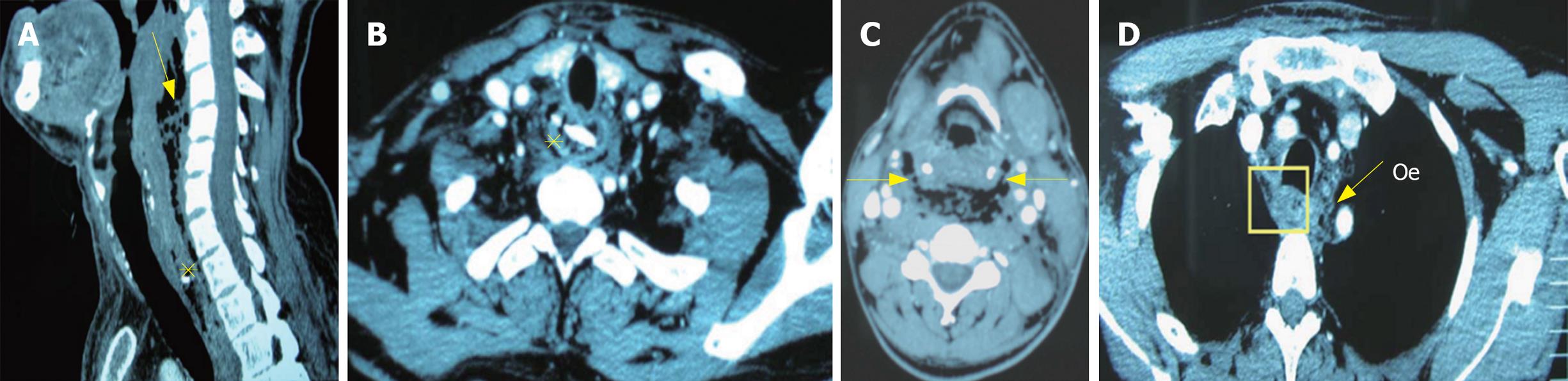

A cervical and thoracic CT-scan revealed a fragment of bone in the upper part of esophagus, air in the retropharyngeal space and the upper part of the posterior mediastinum, and deep subcutaneous collection suggestive of cervical posterior mediastinal collection (Figure 1).

The patient was taken immediately to the operating room for surgical treatment under general anesthesia. Endoscopic examination was performed using a rigid endoscope (Storz Φ 16 mm - L 50 cm, Tuttlingen, Germany) which revealed meat fragments and a piece of chicken bone impacted in the upper esophageal wall, 19 cm from incisors. Meat fragments were aspirated using a 4 mm rigid aspiration; forceful pulling of the FB using forceps caused the edges of the FB to bend, enabling extraction through the rigid esophagoscope. After bone removal, a 4 mm perforation was visible at the site of impaction with pus draining through it. Gastric decompression via a naso-gastric tube was performed.

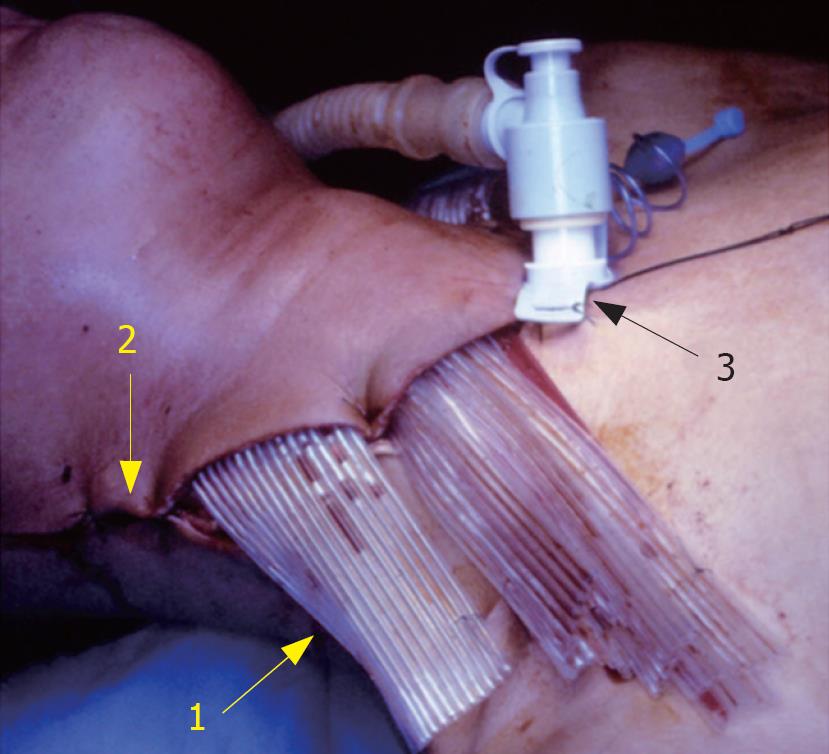

A large neck incision was required to drain the pus from cervical spaces (Figure 2), and the collection in the upper posterior mediastinum was evacuated through the same incision following retropharyngeal space dissection. The drainage of the neck abscess revealed a small bone fragment within the purulent discharge, and cultures were taken. The edges of the perforation were carefully derided and the entire surgical field was well irrigated. The defect was then closed in two layers using fine interrupted absorbable monofilament suture. Drainage of the neck and the upper mediastinum was done by placement of multi-tubular silicone drains through cervical incision. A temporary tracheotomy was performed to bypass the edematous larynx. Broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics (imipenem 2 g/d+ amikacine 1 g/d+ metronidazole 1 g/d), and parenteral hyperalimentation were started. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for 5 d. The patient medical status improved rapidly, and biological laboratory exams were normalized during the first post operative week. Tracheotomy and drains were removed at postoperative d 6 and d 8 respectively. An esophagogram performed at d 10 revealed no leak at the repair site, and oral alimentation was successfully reinstituted. Streptococcus β C hemolytic was isolated from the cultured pus, allowing for switching to amoxicillin and clavulanic acid 4 g/d at postoperative d 3, and continued for 7 d. The patient was discharged from the hospital in good condition on postoperative d 15.

The majority of ingested FBs pass through the gastrointestinal tract uneventfully[1]. Severe complications are rare, but upper digestive tract perforation is the most frequent. Among the esophageal perforation etiologies, FB represent the second most common etiology after iatrogenic manipulation (esophagoscopy, esophageal dilatation, para-esophageal surgery, external trauma)[4]. The diagnosis of esophageal perforation is usually suspected on clinical basis, and suggestive history of sharp bodies ingestion (chicken and fish bones)[5]. Symptoms include pain, dysphagia, and rarely hematemesis; pain is the most frequent symptom (> 90%)[5]. In case of upper esophagus perforation, tenderness and subcutaneous emphysema of the neck are the two main signs. Substernal pain and polypnea are signs associated with mediastinal extension[5]. In these cases, mediastinal crunch (Hamman sign) and crepitations are heard on chest auscultation[6]. Fever and leukocytosis with increase in the number of immature polymorphonuclear cells are present in more than 90% of patients[5].

Standard neck and chest radiograms are ordered if an esophageal perforation is suspected. But these exams reveal esophageal perforation in only a small proportion of cases[7]. Moreover, even if FB is radiopaque, it can be unrecognized because a lot of bone structures are superposed. The perforation diagnosis is confirmed in almost all cases by contrast esophagograms, which can delineate both the level of perforation and the communication of the injury into cervical and mediastinal spaces[67]. CT-scan allows the visualization of FB and the identification of findings suggestive of esophageal perforation (esophageal wall thickening and laceration, peri-esophageal air and fluid). Intravenous administration of contrast material helps CT-scan localization of the exact extension of peri-esophageal infection in the neck, mediastinal, and pleuro-parenchymal spaces[8]. Its sensitivity can be increased with gastrografin ingestion. Thus, an appropriate CT examination enables an accurate and timely diagnosis which significantly affects prognosis and provides valuable indications for treatment.

Extraction of FBs located in the first few centimeters under the upper esophageal sphincter, is difficult with a flexible esophagoscope, especially if they have sharp edges, such as bone fragments[9]. Rigid endoscopy may be a more appropriate procedure in these instances. The rigid endoscope is placed just above the proximal tip of the FB; it dilates the esophageal lumen to the extent that the impacted FB is movable. The use of a rigid endoscope during removal of an impacted FB has several advantages: it causes expansion of the upper esophagus, which can release totally or in part the impacted FB, and prevents aspiration and esophageal or pharyngeal injury. It must be practiced under general anesthesia by a trained operator.

Non-operative management is excluded in case of cervical and/or mediastinal abscesses[4]. Different surgical approaches are available for esophageal perforation, including primary repair with drainage, generally chosen for patients without evidence of a severe esophageal injury and without other esophageal disease[10]. A simple suture is recommended in case of small perforation in the cervical esophagus[5]. It is not necessary to use mucosal flaps to reinforce the esophageal sutures, contrarily to the recommendations for injuries of the middle and lower parts of esophagus[11]. In case of cervical abscess and/or mediastinitis, drainage of the different affected spaces must be done[12]. The choice of surgical approach for mediastinal drainage is dependent on abscess localization. In case of posterior and superior mediastinitis, drainage from cervical incision with retropharyngeal space dissection is adopted. Prognosis in case of upper esophageal perforation is relatively good with mortality inferior to 10%[5].

In conclusion, perforation of the upper esophagus caused by a FB is rare, but can cause potentially life threatening mediastinal complications. CT-scan enables accurate and timely diagnosis and provides valuable indications for treatment. Extraction of esophageal FB with a rigid endoscope is a good and safe treatment alternative. Non-operative management of esophageal perforation is not an option in the presence of neck and mediastinum abscesses and necessitates a surgical suture and drainage.

| 1. | Selivanov V, Sheldon GF, Cello JP, Crass RA. Management of foreign body ingestion. Ann Surg. 1984;199:187-191. |

| 2. | Chee LW, Sethi DS. Diagnostic and therapeutic approach to migrating foreign bodies. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1999;108:177-180. |

| 3. | Brinster CJ, Singhal S, Lee L, Marshall MB, Kaiser LR, Kucharczuk JC. Evolving options in the management of esophageal perforation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:1475-1483. |

| 4. | Altorjay A, Kiss J, Voros A, Bohak A. Nonoperative management of esophageal perforations. Is it justified? Ann Surg. 1997;225:415-421. |

| 5. | Michel L, Grillo HC, Malt RA. Operative and nonoperative management of esophageal perforations. Ann Surg. 1981;194:57-63. |

| 6. | Scheinin SA, Wells PR. Esophageal perforation in a sword swallower. Tex Heart Inst J. 2001;28:65-68. |

| 7. | De Lutio di Castelguidone E, Pinto A, Merola S, Stavolo C, Romano L. Role of Spiral and Multislice Computed Tomography in the evaluation of traumatic and spontaneous oesophageal perforation. Our experience. Radiol Med (Torino). 2005;109:252-259. |

| 8. | Exarhos DN, Malagari K, Tsatalou EG, Benakis SV, Peppas C, Kotanidou A, Chondros D, Roussos C. Acute mediastinitis: spectrum of computed tomography findings. Eur Radiol. 2005;15:1569-1574. |

| 9. | Seo YS, Park JJ, Kim JH, Kim JY, Yeon JE, Kim JS, Byun KS, Bak YT. Removal of press-through-packs impacted in the upper esophagus using an overtube. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5909-5912. |

| 10. | Cheynel N, Arnal E, Peschaud F, Rat P, Bernard A, Favre JP. Perforation and rupture of the oesophagus: treatment and prognosis. Ann Chir. 2003;128:163-166. |

| 11. | Fell SC. Esophageal perforation. Esophageal surgery. New York: Churchill Livingstone 1995; 495-515. |

| 12. | Righini CA, Motto E, Ferretti G, Boubagra K, Soriano E, Reyt E. Diffuse cervical cellulites and descending necrotizing mediastinitis. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. 2007;124:292-300. |