INTRODUCTION

Acute recurrent pancreatitis (ARP) is still a complex diagnostic and therapeutic challenge in clinical practice. Defining the diagnosis itself is already problematic; it is sometimes impossible to differentiate clearly between recurrent attacks of acute pancreatitis and the early stages of chronic pancreatitis. The history and presenting symptoms may be non-specific, and as a consequence up to four out of ten patients may be initially misdiagnosed as having “non-specific dyspepsia”[1]. It is difficult to assess the significance of mild or early changes in the pancreatic duct system and the pancreatic parenchyma, particularly because the normal appearance of the pancreas already varies widely with age. In up to 30% of cases of recurrent acute pancreatitis, it is not possible to establish the etiology of the disease, despite a detailed history and extensive investigations[2], so as a result the patient is diagnosed as having “idiopathic” ARP.

In the other 70%, many factors play an etiological role in ARP; in fact, virtually any case of acute pancreatitis may lead to recurrent episodes if it is not corrected. In these patients, more extensive evaluation may lead to a diagnosis of microlithiasis, sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SOD), or pancreas divisum. Less commonly, hereditary pancreatitis, cystic fibrosis, a choledochocele, annular pancreas, an anomalous pancreatobiliary junction, pancreatic tumors or chronic pancreatitis are diagnosed. Gullo et al[3] reported that 288 (27%) of the total of 1068 acute pancreatitis patients had recurrence, and alcohol was the most frequent factor.

In virtually all patients with normal upper gastrointestinal anatomy, endoscopic ultrasound EUS makes it possible to visualize the entire pancreas, the neighboring blood vessels, and the common bile duct from various scanning positions in the stomach and duodenum. This is not always possible with abdominal US because the images can be compromised by intestinal gas or fat, and the local resolution provided by the endosonographic images is unsurpassed by any other imaging method because of the close proximity of the pancreas to the stomach and proximal duodenum. In contrast to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), EUS makes it not only possible to view changes in the pancreatic duct, but changes in the parenchyma can also be taken into account for diagnostic considerations.

The normal endosonographic appearance of the pancreas should meet specific criteria for size, contour, parenchyma, and ducts. Wiersema et al[4] evaluated the endosonographic features of a small group of healthy volunteers, with no history of abdominal pain or alcohol abuse. To diagnose pathological changes in the pancreas, it is important to take account of the normal anatomical variants. Normally, the pancreatic parenchyma is homogeneous and slightly hyperechoic. The main pancreatic duct is seen as a thin, anechoic, smooth linear structure coursing centrally through the parenchyma. There is also usually a clearly detectable difference in the echo-density of the ventral and dorsal pancreas, the ventral part being more hypoechoic[5]. Age-related changes can also vary widely. In a large prospective study, Rayan et al[6] found that 28% of patients with no history or symptoms of pancreaticobiliary disease had at least one pancreatic parenchymal or ductular finding similar to those seen in chronic pancreatitis. There was a tendency, albeit not significant, for the frequency of abnormalities to rise with age, particularly after the age of 60[6].

Mechanical factors promote recurrent episodes of pancreatitis by inducing a transient, or less frequently, a persistent obstruction to the flow of pancreatic juice into the duodenum, with a consequent rise in intraductal pancreatic pressure. The mechanical obstruction may also allow the bile to flow back into the main pancreatic duct with intrapancreatic activation of pancreatic zymogens; Opie first proposed this theory in 1901[7] for the pathogenesis of gallstone pancreatitis. Conditions inducing mechanical obstruction are either congenital or acquired and may be at the level of Vater’s papilla, the bilio-pancreatic junction or the main pancreatic duct.

If EUS and MRCP exclude mechanical causes of pancreatitis, an autoimmune form should be considered, especially if the patient has any other “rheumatologic” conditions such as sicca syndrome, and has elevated serum IgG 4 levels. EUS shows an irregular narrowing of the pancreatic duct, with swelling of the parenchyma. There may be diffuse parenchymal enlargement, sometimes also of the pancreatic main duct. Obstructive jaundice can be a common feature. The lesion sometimes mimics a pseudotumor and differential diagnosis with adenocarcinoma becomes difficult. In autoimmune pancreatitis the Wirsung is often narrowed, but not disrupted as in cancer. Fine-needle aspiration shows lympho-plasmacytic infiltration and fibrosis, more evident in cases with a long history of recurrent pain.

CHOLEDOCHOLITHIASIS AND BILIARY MICROLITHIASIS

Pancreatitis results from gallstone disease (Figure 1) in almost 40% of cases[8]. With the US probe positioned in the genu superior, the common bile duct (CBD) can be examined in longitudinal sections as far proximally as the hepatic duct and distally to the ampulla (Figure 2). Withdrawal from the bulb under traction allows examination of the gallbladder and CBD, from its origin in the hilum to the convergence of the cystic and hepatic ducts and the proximal portion of the CBD. With this method, the hepatic duct and CBD can be visualized in 95%-100% of patients, as reported in several studies[9].

Figure 1 Conventional endosonographic imaging (7.

5 MHz) of choledocholithiasis. A 9.6 mm stone (A) is seen as an hyperechoic structure with acoustic shadowing (C) in the intrapancreatic tract of the common bile duct (B).

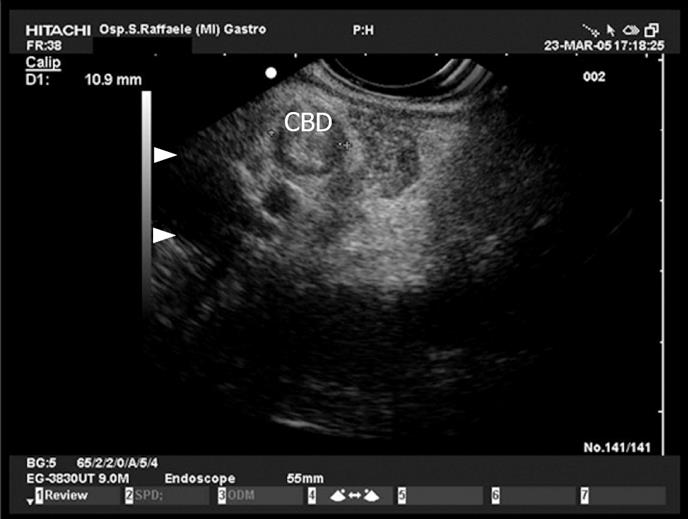

Figure 2 Common bile duct (CBD) stone with dilation of the biliary tract.

PAP: Vater papilla.

In a prospective and competitive blinded study in patients with CBD obstruction EUS gave 100% accuracy for the diagnosis of choledocholithiasis; it was also significantly more sensitive than transabdominal ultrasonography or CT[10]. In patients with unexplained ARP the use of EUS with high resolution increases the chances of detecting microlithiasis (Figure 3), a frequent cause of pancreatitis[21112].

Figure 3 View of the proximal tract of the common bile duct (CBD) from the duodenum: the duct is dilated and completely obstructed by minuscule concrements (microlithiasis).

A large study by Frossard et al evaluated 168 patients referred with diagnosis of idiopathic pancreatitis. EUS identified an abnormality in 80% of these patients, and 62% of them had biliary tract pathology such as stones, sludge, or microlithiasis. Compared to the final diagnosis at surgery, ERCP, bile crystal analysis, or medical follow-up, EUS correctly established the causes of pancreatitis in 92% of patients[13] (Figure 4).

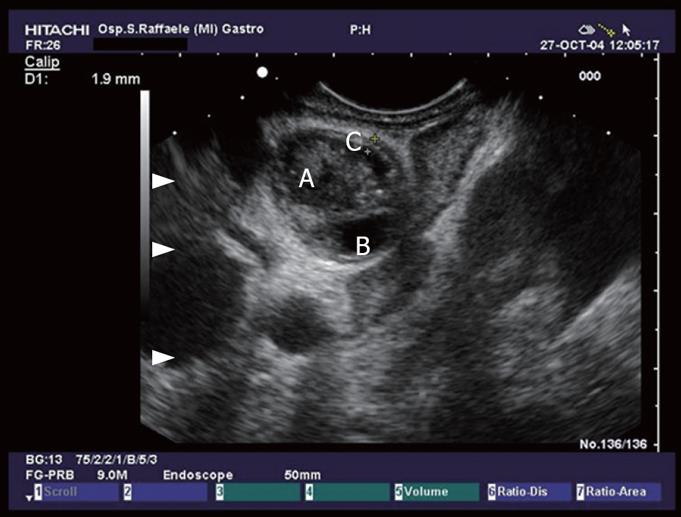

Figure 4 Hepatic ilum seen from the duodenal bulb: common bile duct with sludge (A), thickening of the CBD wall (C), and cystic duct (B).

Microlithiasis may lead to pancreatitis through several mechanisms: transient impaction of small stones at the papilla, obstructing the pancreatic duct, or the repeated passage of stones (which may lead to papillary stenosis or SOD, both of which are associated with pancreatitis)[14]. Surgical or endoscopic treatment of occult microlithiasis significantly reduces the recurrent episodes of acute pancreatitis compared with untreated patients[5–21].

Three recent studies maintain that EUS should replace ERCP as the first procedure in patients with mild to moderate acute pancreatitis to avoid unnecessary ERCP and thus reduce ERCP-induced morbidity[22–24]. One study also suggested that the rate of morbidity and mortality could be reduced by systematically using EUS in cases of acute pancreatitis, followed by ERCP with sphincterotomy when EUS has indicated CBD stones[25].

When gallstone disease is excluded as a cause of pancreatitis, EUS remains obligatory in the work-up of patients with idiopathic pancreatitis because it permits combined exploration for parenchymal and ductal abnormalities.

PANCREAS DIVISUM

Pancreas divisum (PD) is the most common congenital anatomic variant in the pancreas, present in 5%-8% of the general population, with reports of prevalence ranging from 1.3% to 7.5% in series based on ERCP findings[26–29]. PD occurs when the ventral and dorsal pancreatic ducts fail to fuse during embryogenesis. As a result, the ventral duct only drains the ventral pancreas. The majority of the pancreas then drains through the dorsal duct from the minor papilla. In these patients, the minor papilla is often stenotic and therefore slows the flow of pancreatic juice. Even relative obstruction of pancreatic exocrine secretory flow through the minor papilla can result in pancreatitis in some patients. Patients with PD and ARP respond favourably to surgical sphincteroplasty of the minor papilla or endoscopic minor papilla sphincterotomy[30].

By definition, EUS findings are indicative of PD if the course of the pancreatic duct cannot be followed from its origin at the ampulla of Vater through the ventral part to the dorsal pancreas, or if the duct cannot be visualized within the ventral pancreas. It may also sometimes be possible to visualize the separate orifices of the CBD at the major papilla and of the dorsal pancreatic duct at the minor papilla (Figure 5). Conversely, PD can be excluded if the pancreatic duct can be followed continuously from the ventral to the dorsal pancreas, or between the papilla of Vater and the pancreatic neck[3132].

Figure 5 Pancreas divisum.

The pancreatic duct at the istmus moves towards the minor papilla (B), (A) dorsal pacreatic duct, (C) superior mesenteric vein.

Bhutani et al described the possibility of accurately diagnosing PD by EUS using radial instruments[33] and suggested that divisum was present if an image simultaneously showing the portal vein, CBD, and main pancreatic duct could not be obtained[33]. In another study, Lai et al[32] showed that linear-array EUS appeared to be a promising, minimally invasive diagnostic imaging approach for the detection of PD, with 97% accuracy (Figure 6). Catalano et al, using dynamic endosonography with secretin stimulation, were able to identify patients with chronic pancreatitis and PD who subsequently benefited from endoscopic stent placement[34].

Figure 6 A view of Santorini’s duct (A) from the duodenal bulb, with millimetres stones in the retropapillary region (B) (minor papilla).

ANOMALOUS PANCREATOBILIARY JUNCTION

The CBD and PD normally unite in the wall of the duodenum at the ampulla of Vater and are surrounded by a muscular sheath, the sphincter of Oddi. The ampulla is easily visualized with the probe placed in the second part of the duodenum with the balloon and the lumen filled with water, and it is seen as a clearly outlined hypoechoic structure, from which the two ducts can be followed into the pancreatic head.

An anomalous pancreatobiliary junction (PBJ) is defined by an abnormally long (> 15 mm) common pancreatobiliary channel[35]. This anomaly is associated with idiopathic ARP, choledochal cyst, and cholangiocarcinoma[36]. The sphincter does not separate the bile and pancreatic ducts, so pancreatic and bile juices may freely flow between ducts and lead to pancreatitis. ERCP and injection of the major papilla reveal the long common channel and simultaneous filling of the bile and pancreatic ducts. EUS may also establish the diagnosis.

In a prospective study Sugiyama et al[37] assessed the diagnostic value of EUS for anomalous PBJ. They examined 188 patients with pancreatobiliary disease, and the length of the common channel indicated by EUS was compared with that found by ERCP. EUS showed the common channel was longer than 12 mm in 88% of cases of anomalous PBJ.

ANNULAR PANCREAS

Annular pancreas is a rare congenital anomaly of the pancreas that consists of an aberrant band of pancreatic tissue arising from the head of the pancreas and either partially or completely encircling the second portion of the duodenum[38]. This abnormality is detected in 1/7000 autopsies and about 1/1500 ERCPs[39]. Adults may present with abdominal pain, ARP, or chronic pancreatitis. Although CT or MRCP may suggest the diagnosis, ERCP is usually required for confirmation. Gress et al described two cases where the addition of EUS aided in the diagnosis of annular pancreas visualized as “salt and pepper” parenchyma around the duodenum[40].

PANCREATIC TUMORS

Five to seven percent of patients with benign or malignant pancreatic tumors present with ARP[41]. Patients with adenocarcinoma (ADC) may suffer attacks of pancreatitis for months before cross-sectional imaging identifies a mass. EUS can be helpful in these cases but though a negative EUS result is reassuring if there is a strong clinical suspicion of ADC, it is mandatory to repeat the procedure periodically (3-6 mo) (Figure 7). Cystic lesions that cause duct compression or involvement of the main pancreatic duct tend to cause pancreatitis. EUS identified all tumoral causes in a recent series of 90 patients with undetermined causes of acute or recurrent pancreatitis[2].

Figure 7 A malignant lesion (A) in the pancreatic head occluding the main pancreatic duct wich is dilated (B).

Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas are traditionally organized according to the type of lining epithelium since this feature dominates the risk of malignancy and management. There are three types of mucinous lesion, benign mucinous cystadenoma, malignant mucinous cystic lesions, and intraductal papillary neoplasms. The non-mucinous lesions include serous cystadenomas and can be generally managed with observation alone. It is sometimes difficult to distinguish between serous and mucinous tumors, since the latter may contain enzyme-rich fluid, communicate with the ductal system, and may be seen more frequently in patients with symptoms of ARP. EUS can provide the means of distinguishing between serous and mucinous neoplasms by revealing a mass composed either of many tiny cysts (microcystic), with a solid-appearing hypervascular tumor, or several large cysts (macrocystic)[42].

Mucinous cystadenomas consist of one or more macrocystic spaces lined with mucus-secreting cells and are typically found in the body or tail of the pancreas. When the diagnosis of a mucinous cystadenoma is made, the lesion should be resected, on account of the high potential for malignant change.

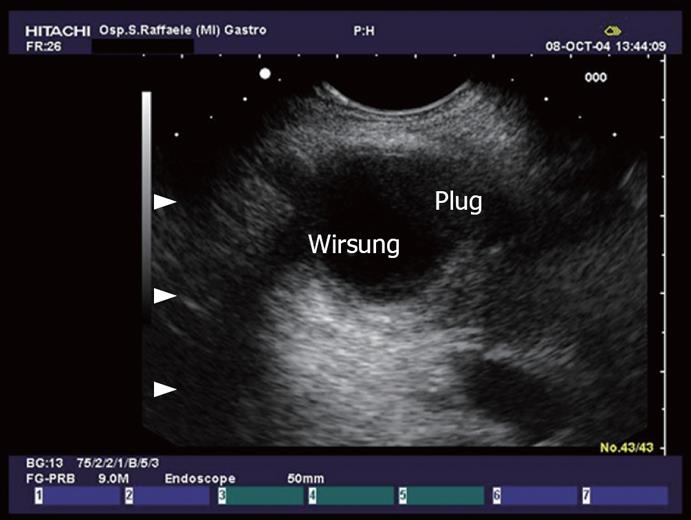

A more frequent cause of single or recurrent episodes of acute pancreatitis is intraductal papillary mucinous tumors (Figure 8) of the pancreas (IPMT)[43]. These are villous or papillary tumors of the main pancreatic duct and/or its branches. IPMT have been subdivided (Kuroda et al) into a main duct and a branch duct based on the anatomical involvement of the pancreatic duct (Figure 9). EUS findings in IPMT include segmental or diffuse, moderate to marked dilatation of the main pancreatic duct, often with intraductal nodules. Pancreatic parenchymal atrophy is frequent[44] (Figure 10). Dilation of the pancreatic duct to over 10 mm and cysts larger than 20 mm are suggestive of malignancy. EUS-FNA of the dilated pancreatic duct, including mural nodules and especially solid components of the tumor, may be helpful in the diagnosis. Histologically, the normal ductal epithelium is replaced by a mucinous metaplasia, with a broad spectrum of histopathological disorders from hyperplasia to ADC. IPMTs have been reported in elderly men, with an average age between 60 and 70 years, but can sometimes arise in younger patients. In comparison with mucinous cystadenomas, they have a lower but still relatively high malignant potential.

Figure 8 Dilation of the main pancreatic duct and collateral duct with evidence of plugs in the lumen in a patient with IPMT.

Figure 9 IPMT.

A small cystic lesion (C) in retropapillary region (A), that seems to communicate with main pancreatic duct (B).

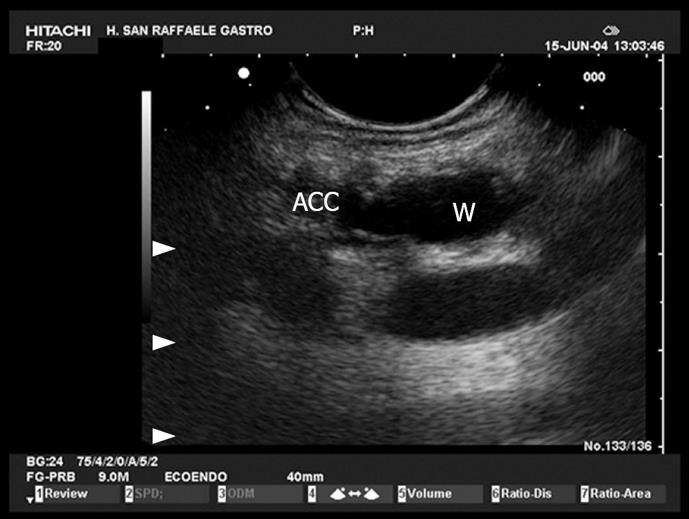

Figure 10 IPMT.

Dilation of the main pancreatic duct and accessory duct. The sorrounding parenchyma is hypotrofic, hypoechoic.

Ampullary tumors too-either benign or malignant - may present with ARP. Specifically, the papilla consists of the circular muscle of the CBD and an additional circular muscle enclosing the two ducts. It is seen as a hypoechoic structure from which the CBD and the main pancreatic duct can be traced and followed into the pancreatic head (Figure 11).

Figure 11 Normal ampulla.

The ampulla (A) is seen as an hypoechoic structure from which the two ducts, the common bile duct (B) and the Wirsung (C) can be followed into the pancreatic head.

CHRONIC PANCREATITIS

Although patients may present clinically with ARP, many will be found, after pancreatic function tests and EUS, to have already developed some degree of chronic pancreatitis (CP). The first diagnostic endosonographic criteria of CP were suggested by Lees et al in 1979[45]. In 1993, Wiersema et al [4] refined these criteria, which can be divided into two groups: parenchymal and ductal.

Parenchymal criteria include reduced echogenicity, lack of homogeneity, loss of ventral/dorsal distinction, atrophy, hyperechoic foci, hyperechoic strands (Figure 12), and lobularity[5]. They should be sought in the dorsal gland only because the hypoechoic ventral pancreas can show features such as hyperechoic foci and strands even in normal individuals. Reduced echogenicity and lack of homogeneity are presumably caused by edema and/or reduced fat content. These changes in the dorsal gland would explain the loss of ventral/dorsal distinction. Hyperechoic foci and strands correspond respectively to small hyperechoic dots and thin, hyperechoic lines scattered in the parenchyma. When there are enough strands, they divide the parenchyma up into distinct “lobules” that may give the gland a honeycomb appearance. Information on the histologic correlates of these features is scant, but they may represent thickened fibrous deposits or may simply reflect increased visibility of normal connective tissue because of surrounding edema[46].

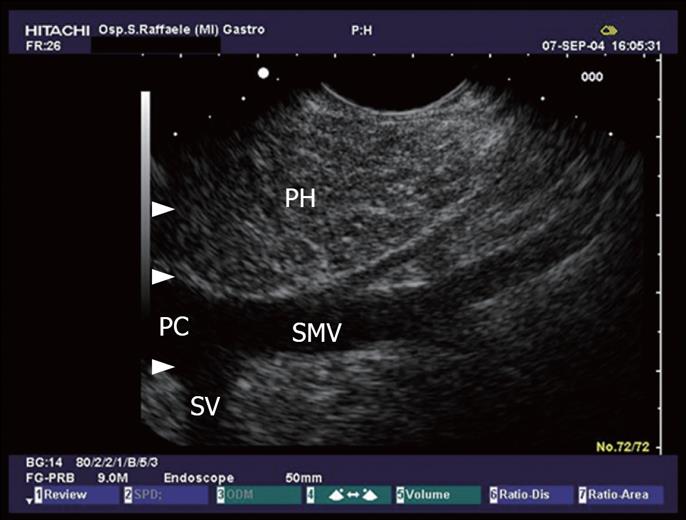

Figure 12 The pancreatic head (PH) seen from the duodenum.

Minimal changes like echogenic strains in the echo texture of the pancreatic parenchyma. Portal confluence (PC) with its vessels: the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) and splenic vein (SV).

Ductal criteria specific to EUS include obvious to more subtle ductal dilation (> 3 mm in the head, ≥ 2 mm in the body, > 1 mm in the tail), hyperechoic main duct margins, irregular main duct margins, and visible side branches[5]. Normally, the duct walls are invisible; if they become visible, they may be considered hyperechoic.

A quantitative analysis with nine possible criteria (hyperechoic foci, hyperechoic strands, lobularity, ductal dilation, ductal irregularity, hyperechoic duct margins, visible side branches, calcifications, and cysts) suggests that, in a population at low to moderate risk of CP EUS is most reliable only when it is either clearly normal (< 2 criteria) or clearly abnormal (> 5 criteria). If three or four criteria are present, the outcome is equivocal.

With aging, the pancreas may become atrophic and appear less homogeneous, and the pancreatic duct may become slightly dilated[6]. Alcohol consumption is also associated with parenchymal changes. In a group of 19 alcohol abusers with chronic abdominal pain, 17 (89%) had chronic pancreatitis as indicated by EUS[47].

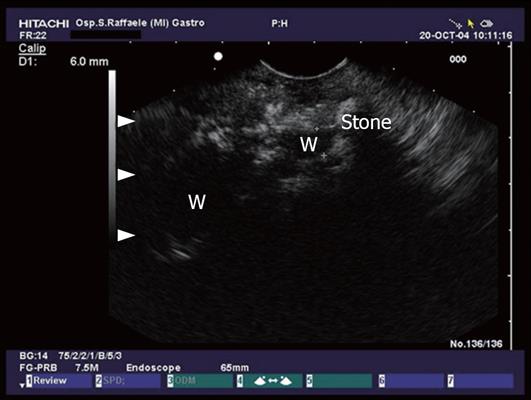

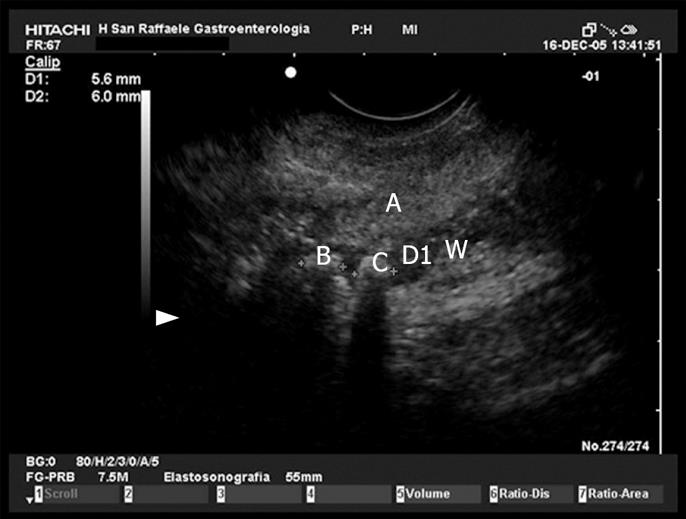

Agreement is moderate between experienced examiners in making a diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis, with either radial systems or curvilinear EUS systems. All studies agree, however, that “calcification” and “calculi” provide the highest diagnostic power (Figures 13 and 14).

Figure 13 Advanced chronic pancreatitis with calcifications, pancreatic stone and dilation of the pancreatic duct.

Figure 14 Pancreatic head (A) and pancreatic duct stones (B and C).

If the initial workup following an attack of acute pancreatitis is negative and successive attacks occur, the evaluation has to include imaging techniques such as EUS, MRCP and blood tests, depending on individual presentation.

In conclusion, EUS should be useful in ARP as it is sensitive for diagnosing bile duct stones, gallbladder sludge, pancreatic lesions, ductal abnormalities and chronic pancreatitis. EUS appears to be diagnostic in the majority of patients with previously unexplained pancreatitis, and offers an alternative to ERCP as the initial diagnostic test in patients with ARP.

Peer reviewer: William Dickey, Altnagelvin Hospital,

Londonderry, BT47 6SB, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom