INTRODUCTION

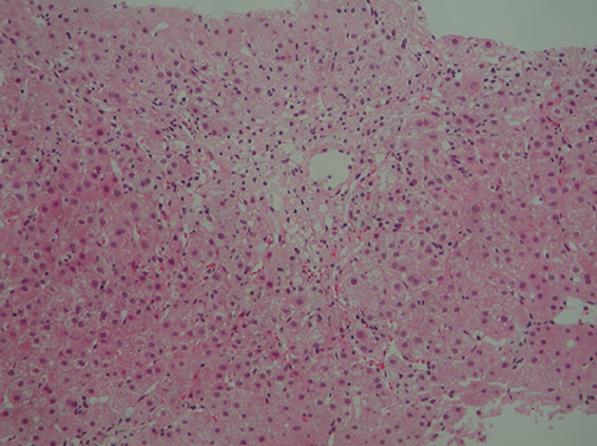

Figure 1 Histological examination of a liver biopsy specimen showing bridging perivenular necrosis and infiltration of inflammatory cells including eosinophils (hematoxylin-eosin staining × 100).

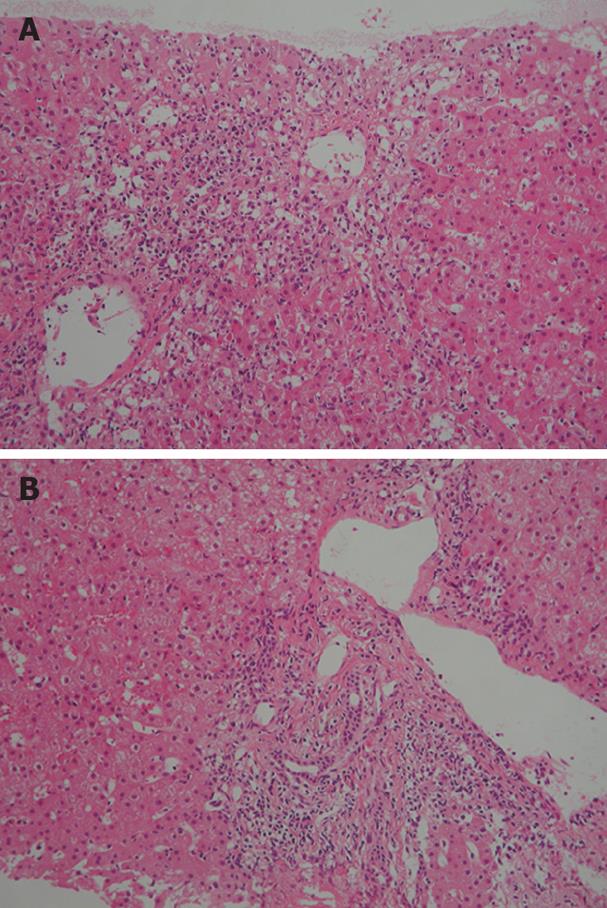

Figure 2 Histological examination of a liver biopsy specimen showing bridging perivenular necrosis (A) and interface hepatitis (B) (HE staining × 100).

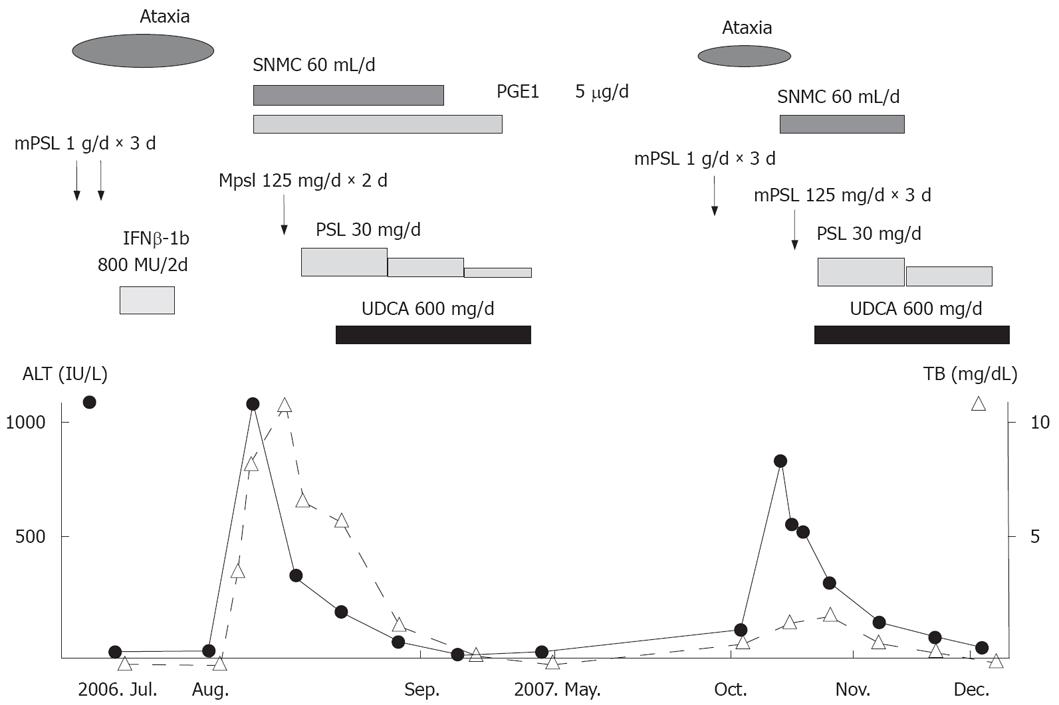

Figure 3 Clinical course of the disease.

SNMC: Stronger neo-minophagen C, PGE1: Prostaglandin, mPSL: Methylprednisolone, PSL: Prednisolone, IFN-β: Interferon β.

Intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy is the standard treatment for relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS). Interferon (IFN)-β is the most commonly used drug in the treatment of MS, and has been proven to reduce the disease activity, progression and relapse rate[1,2]. IFN-β is associated with hepatotoxicity, although it rarely induces severe liver injury. It was reported that autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) occurs during IFN-β therapy for MS[3,4], but only one report has described the occurrence of AIH after intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy for MS[5]. We describe herein a case of a MS patient who developed AIH after treatment with IFN-β and pulsed methylprednisolone.

CASE REPORT

A 43-year-old woman with abdominal discomfort and nausea was referred to our hospital on August 7, 2006. She was diagnosed with MS on the basis of clinical and laboratory findings 7 years ago. Three years ago, she was treated with pulsed methylprednisolone (1000 mg/day for 3 d) followed by 50 mg/day of oral prednisolone because of ataxia. Although oral prednisolone was tapered and stopped for 1 month, she remained healthy until June 2006, when ataxia developed again. On June 28, 2006, she was treated with pulsed methylprednisolone (1000 mg/day for 3 d) followed by 50 mg/day of oral prednisolone. Despite pulsed methylprednisolone therapy, symptoms did not improve. She was therefore retreated with pulsed methylprednisolone (1000 mg/day) for 3 d from July 5, 2006. Moreover, she was treated with IFN-β 8 at MU every other day from July 11 to 26, 2006. After pulsed methylprednisolone, oral prednisolone was not administered. On August 3, 2006, the patient became nauseous and vomited, and these symptoms did not improve. On August 7, 2006, she was referred to our hospital and admitted after blood testing revealed severe liver dysfunction. Three years ago, she developed acute hepatitis due to Epstein-Barr (EB) virus after treatment with pulsed methylprednisolone. Since then, she had been free of liver dysfunction.

On admission, her blood pressure was 156/89 mmHg and heart rate was 102 beats/min, body temperature was 37.3°C, and the areas of skin at sites of IFN-β injection became welts. Her conjunctivae were not jaundiced, heart and respiratory sounds were normal. No abnormalities were noted in the chest or abdomen. The liver and spleen were not palpable. Neurological examination showed no abnormalities suggestive of MS. Laboratory findings were as follows: 1102 IU/L aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (normal, 10-35 IU/L), 1067 IU/L alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (normal, 12-33 IU/L), 377 IU/L alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (normal, 300-500 IU/L), 3.4 mg/dL total bilirubin (TB) (normal, < 1.1 mg/dL), 2.2 mg/dL direct bilirubin (DB) (normal, 0.2-0.4 mg/dL), 26 IU/L γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γGTP) (normal, 10-47 IU/L), 6.4 g/dL total protein (TP) (normal, 6.0-8.5 g/dL), 3.7 g/dL albumin (normal, 4.0-5.3 g/dL), 1370 mg/dL serum immunoglobulin (Ig)G, 147 mg/dL IgA, 272 mg/dL IgM, and 71.4% prothrombin time (PT). Anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), anti-smooth muscle antibody and anti-LKM-1 antibody were all negative. HBs antigens, IgM-HA and HCV antibodies were negative. Other viral infections including EB virus and cytomegalovirus infection were excluded by serological testing. Abdominal computed tomography showed no abnormalities. Biopsy specimen of the liver showed bridging perivenular necrosis with infiltration of inflammatory cells including eosinophils (Figure 1). A lymphocyte-stimulation test for IFN-β yielded negative results, but the patient displayed a score of 9 according to the criteria for drug-induced liver injuries[5], indicating a high probability of drug-induced liver injury. All these findings led to the diagnosis of drug-induced liver injury caused by IFN-β. Despite intravenous administration of stronger neo-minophagen C (60 mL/day) and prostaglandin, jaundice developed with a serum TB level of 19.1 mg/dL. Methylprednisolone (125 mg/day for 3 d) and ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA, 600 mg/day) were therefore administered. Symptoms subsequently improved and serum TB level normalized. Prednisolone was decreased gradually and stopped on April 10, 2007. UDCA was stopped on May 10, 2007. Liver function remained normal even after withdrawal of prednisolone and UDCA.

However, ataxia developed and the patient was again treated with pulsed methylprednisolone (1000 mg/day) for 3 d from October 1, 2007. After pulsed methylprednisolone, oral prednisolone was not administered. Two weeks later, she was readmitted to our hospital due to fatigue and liver dysfunction. Laboratory findings on admission were as follows: 566 IU/L AST, 875 IU/L ALT, 214 IU/L ALP, 1.7 mg/dL TB, 12 IU/L γGTP, 1785 mg/dL IgG, and 71.4% PT. Anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) titer was × 80 with a homogeneous pattern, positive results were obtained for anti-smooth muscle antibody, and HLA DR was 4. Viral infections were excluded by serological testing. Biopsy specimen from the liver revealed bridging perivenular necrosis and interface hepatitis (Figure 2A and B). In this case, IgG was not elevated, which is atypical for AIH. However, according to the criteria for AIH[6], the patient had a score of 16 on the second admission, indicating definite AIH, compared to a score of 9 on the first admission. Conversely, according to the criteria for drug-induced liver injury[7], our patient displayed a score of 2, indicating a low possibility that this case represented drug-induced liver injury. Moreover, lymphocyte-stimulation testing for methylprednisolone yielded negative results.

These clinical and laboratory findings supported the diagnosis of AIH. After administration of prednisolone and UDCA, symptoms and liver function improved. The charts for the overall clinical course are shown in Figure 3. Her condition is now under control with prednisolone, 10 mg/day.

DISCUSSION

MS is an inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system. Liver dysfunction is not always caused by MS itself, but can result from many factors, such as drug toxicity, fatty infiltration and viral infection. Liver dysfunction in patients with MS is most commonly caused by drugs. IFN-β, which raises serum ALT level as a side effect, is one of the drugs well known to cause liver injury in patients with MS.

Tremlett et al[8] reported that 36.9% of patients with MS develop new elevations of ALT, although only 1.4% reach grade 3 hepatotoxicity (> 5-20 upper limit of normal). In patients with MS receiving IFN-β, if de novo elevation of aminotransferases is mild, IFN-β treatment is often continued, and elevated aminotransferases return to almost normal[4]. However, severe liver dysfunction does not resolve simply after stopping IFN-β, and prompt treatment is needed. A case of fulminant liver failure occurring during IFN-β treatment has been reported[9]. Our patient satisfied the criteria for drug-induced hepatitis, but not for AIH on the first admission. Byrnes et al[10] have also reported drug-induced liver injury secondary to IFN-β in patients with MS. However, the precise mechanisms underlying IFN-β-induced hepatotoxicity remain unclear.

IFN-β may cause autoimmune complications including thyroiditis, lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis[11]. Duchini et al[3] have reported a case of AIH occurring during treatment with IFN-β. Conversely, Reuβ et al[5] have reported a case of AIH that developed after high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone pulse in MS and speculated that AIH may occur in patients with multiple autoimmunity as an immune rebound phenomenon after immunosuppressive regimens.

The typical histological pattern of AIH is chronic active hepatitis that shows portal inflammation with fibrosis, interface hepatitis and rosette formation of hepatocytes. However, few cases of AIH with centrilobular necrosis (CN) as the dominant finding have been reported[12]. Recently, some cases of CN with autoimmune features have been confirmed as early-stage AIH[13,14]. Acute-onset AIH sometimes does not satisfy AIH criteria serologically and shows CN histologically[14-16]. Although our patient showed a typical pattern of AIH at the second admission, liver dysfunction at the first admission may have been due to early-stage AIH.

The cause of AIH in this patient was an immune rebound phenomenon after pulsed methylprednisolone, because the second episode of liver dysfunction occurred after pulsed methylprednisolone therapy rather than after IFN-β therapy. In fact, some reports have described AIH occurring in patients with multiple autoimmunity after pulsed methylprednisolone therapy[5,17-18]. In particular, withdrawal of glucocorticoids after pulsed methylprednisolone therapy might have induced immune rebound phenomenon in the present case. However, we cannot deny the possibility that AIH was induced by IFN-β in this patient. She received IFN-β treatment before the first admission. Moreover, Misdraji et al[12] reported that AIH with CN occurs after IFN-β therapy in patients with MS.

In conclusion, the prevalence of AIH seems to be about 10-fold higher in patients with MS than in the general population[19]. Attention should be paid to the development of AIH after pulsed methylprednisolone or IFN-β treatment in patients with MS, and if AIH develops, immediate treatment with corticosteroids or azathioprine should be initiated. Moreover, administration of corticosteroids or azathioprine after pulsed methylprednisolone might be effective for preventing the development of AIH.