Published online Mar 14, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1633

Revised: January 6, 2008

Published online: March 14, 2008

A 41-year-old man presented with a 6-mo history of changed defecation and rectal bleeding. A 3-cm polypoid tumor of the lower rectum was found at rectosigmoidoscopy, which proved to be a leiomyosarcoma upon biopsy. Dissemination studies did not show any metastases. He was underwent to an abdomino-perineal resection (APR). Histopathology of the specimen showed a melanoma (S-100 stain positive). Two years after the resection, metastases in the abdomen and right lung were found. He died one and half years later. Primary anorectal melanoma is a rare and very aggressive disorder. According to current data, one should always perform a S-100 stain when anorectal sarcoma is suspected. A positive S-100 stain suggests the tumour to be most likely a melanoma. Subsequently, thorough dissemination studies need to be performed. Depending on the outcome of the dissemination studies, a surgical resection has to be performed. Nowadays, a sphincter-saving local excision combined with adjuvant loco-regional radiotherapy should be preferred in case of small tumors. The same loco-regional control is achieved with less “loss of function” compared to non-sphincter saving surgery. Only in the case of large and obstructing tumors an abdomino-perineal resection is the treatment of choice.

- Citation: Schaik PV, Ernst M, Meijer H, Bosscha K. Melanoma of the rectum: A rare entity. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(10): 1633-1635

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i10/1633.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.1633

The majority of colorectal and anal malignancies are adenocarcinomas and squamous cell cancers. Despite the predominance of these neoplasms at these locations, rare histotypes of the colon, rectum, and anus occur. These histotypes include lymphoma, melanoma, diffuse cavernous hemangioma, and sarcomas, such as leiomyosarcoma or Kaposi’s sarcoma.

Primary anorectal melanoma is a rare disorder. About 1% of all anorectal carcinomas are melanomas[12], typically presenting in the fifth or sixth decade of life and predominantly in woman. Patients present themselves with local symptoms like rectal bleeding and a changed defecation pattern[1–6]. Prognosis is very poor with a median survival of 24 mo and a 5-year survival of 10%[3]. Almost all patients die because of metastases[4]. At this moment there is no consensus on which surgical approach is favourable. The surgical procedure of choice ranges from an abdomino-perineal resection to local excision with or without adjuvant radiotherapy.

A 41-year-old man was admitted with a 6-mo history of modified defecation and rectal bleeding. His past history was unremarkable, and his family history was negative for colon and/or rectal carcinoma. He had lost some weight, despite maintaining a good appetite. By physical examination, a 4 cm nodular mass was palpated just behind the anal verge.

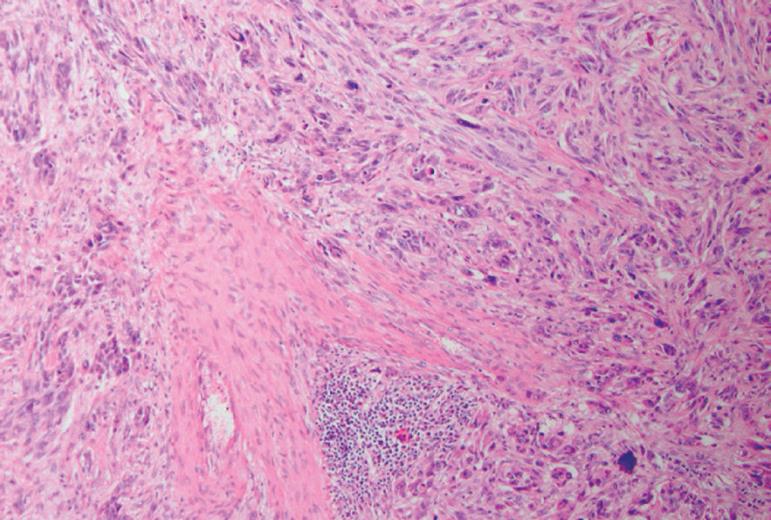

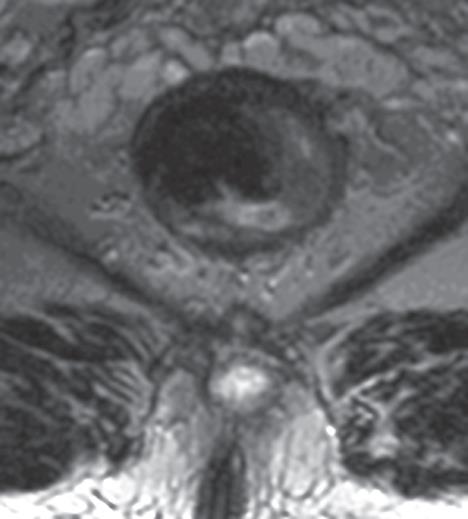

Rectosigmoidoscopy demonstrated a polypoid tumor with a diameter of 3 cm, involving half the circumference. Histopathological examination delineated the tumor as a leiomyosarcoma (Figure 1). MRI showed a tumor just behind the anal verge, without evidence of invasion in the sphincter, growth outside the rectum or enlarged lymph nodes (Figure 2). Abdominal ultrasonography showed no evidence for metastases, especially not in the liver. X-ray of the thorax and CT-thorax were free from any signs of metastases.

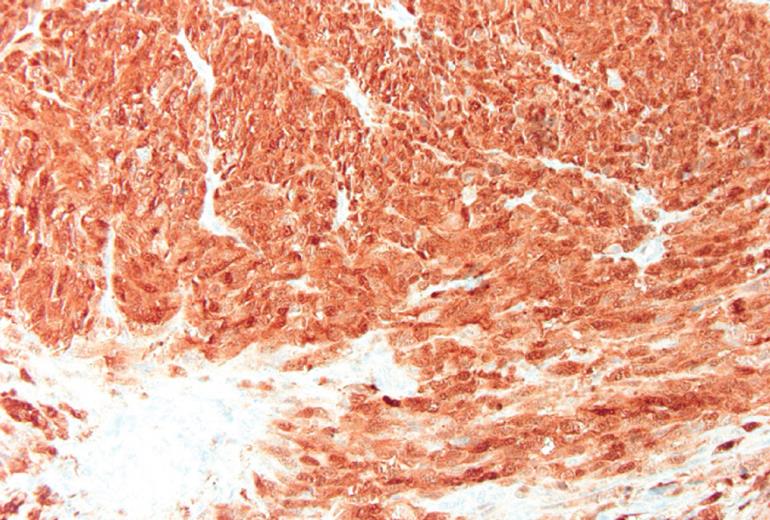

An abdomino-perineal resection was performed. The postoperative period was uneventful. Histopathology of the resected specimen showed a melanoma (S-100 stain positive) (Figure 3).

Two years after the initial diagnosis, metastases in the abdomen were found with growth into the second lumbar vertebra and in the right lung. The patient was treated with radio-chemotherapy with good locoregional response. He underwent a metastasectomy of the right lung following radiochemotherapy. The postoperative period was uneventful and the disease seemed to be in remission. Three and a half year after the initial diagnosis, however, he died because of intra-abdominal metastases.

A malignant melanoma of the rectum is a rare and very aggressive rectal disorder[1–6]. This disease presents itself usually starting from the fourth decade, predominantly in women, with an increase of incidence in the fifth or sixth decade of life[5]. Almost 60% of patients have already metastases at initial diagnosis[2]. Patients often present with rectal bleeding and tenesmus[1–6].

If a biopsy shows a specimen suspicious for sarcoma (e.g. leiomyosarcoma), one should be alert. Preferably, S-100 staining should be performed in addition to routine stainings. A positive S-100 stain suggests the tumour most likely to be a melanoma. Subsequently dissemination studies, including chest X-ray and CT-scan of chest/abdomen/pelvis are performed. Curative surgical resection has to be performed in the absence of metastases proven by dissemination studies.

There is no consensus at this moment on which surgical approach is preferred.

A number of studies claim that an abdomino-perineal resection (APR) is the treatment of choice[78]. This is based on the hypothesis that the disease spreads proximally via the submucosa to the mesenteric lymph nodes. Retrospective studies have revealed a statistically significant improvement in local-regional control when patients are managed with APR compared with local excision alone (without radiotherapy) (74% vs 34%)[5].

Other studies, however, have recommended only a sphincter-saving excision for two reasons. Firstly, treatment is often palliative and wide radical surgery unnecessary mutilating. Secondly, tumor stadium and biological behaviour of the tumor determines survival instead of the choice of surgical operation[910].

Recent studies show that sphincter-saving local excision combined with adjuvant loco-regional radiotherapy at the primary site of the tumor and the regional pericolic and inguinal lymphatics (5 X 6 GY) results in the same loco-regional control with less loss of function compared to APR (70% vs 74%)[5].

Local excision seems to be the treatment of choice in case of small tumors, because of lower morbidity compared to APR. Only in the case of large and obstructing tumors, an APR is the surgical treatment of choice.

In conclusion, a malignant melanoma of the rectum is a rare disorder. The prognosis is poor and patients often have already metastases at the time of diagnosis. If a biopsy shows a sarcoma, the S-100 stain should be performed in addition to routine stainings. A positive staining strongly suggests a melanoma. The first choice, among surgical treatments, seems to be local excision with adjuvant radiotherapy. Only in the case of large and obstructing tumors one should perform an abdomino-perineal resection.

| 1. | Roviello F, Cioppa T, Marrelli D, Nastri G, De Stefano A, Hako L, Pinto E. Primary ano-rectal melanoma: considerations on a clinical case and review of the literature. Chir Ital. 2003;55:575-580. |

| 2. | Takahashi T, Velasco L, Zarate X, Medina-Franco H, Cortes R, de la Garza L, Gamboa-Dominguez A. Anorectal melanoma: report of three cases with extended follow-up. South Med J. 2004;97:311-313. |

| 3. | Solaz Moreno E, Vallalta Morales M, Silla Burdalo G, Cervera Miguel JI, Diaz Beveridge R, Rayon Martin JM. Primary melanoma of the rectum: an infrequent neoplasia with an atypical presentation. Clin Transl Oncol. 2005;7:171-173. |

| 4. | Maqbool A, Lintner R, Bokhari A, Habib T, Rahman I, Rao BK. Anorectal melanoma--3 case reports and a review of the literature. Cutis. 2004;73:409-413. |

| 5. | Ballo MT, Gershenwald JE, Zagars GK, Lee JE, Mansfield PF, Strom EA, Bedikian AY, Kim KB, Papadopoulos NE, Prieto VG. Sphincter-sparing local excision and adjuvant radiation for anal-rectal melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4555-4558. |

| 6. | Kayhan B, Turan N, Ozaslan E, Akdogan M. A rare entity in the rectum: Malignant melanoma. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2003;14:273-275. |

| 7. | Brady MS, Kavolius JP, Quan SH. Anorectal melanoma. A 64-year experience at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:146-151. |

| 9. | Thibault C, Sagar P, Nivatvongs S, Ilstrup DM, Wolff BG. Anorectal melanoma--an incurable disease? Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:661-668. |