Published online Mar 7, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i9.1422

Revised: December 1, 2006

Accepted: February 12, 2007

Published online: March 7, 2007

AIM: To evaluate the long-term outcome and prognostic factors of patients with hilar cholangiocarinoma.

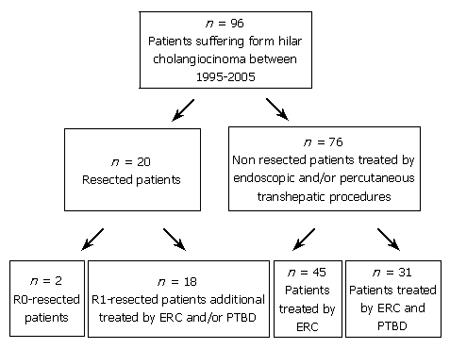

METHODS: Ninety-six consecutive patients underwent treatment for malignant hilar bile duct tumors during 1995–2005. Of the 96 patients, 20 were initially treated with surgery (n = 2 R0 / n = 18 R1). In non-operated patients, data analysis was performed retrospectively.

RESULTS: Among the 96 patients, 76 were treated with endoscopic transpapillary (ERC, n = 45) and/or percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD, n = 31). The mean survival time of these 76 patients undergoing palliative endoscopic and/or percutaneous drainage was 359 ± 296 d. The mean survival time of patients with initial bilirubin levels > 10 mg/dL was significantly lower (P < 0.001) than patients with bilirubin levels < 10 mg/dL. The mean survival time of patients with Bismuth stage II (n = 8), III (n = 28) and IV (n = 40) was 496 ± 300 d, 441 ± 385 d and 274 ± 218 d, respectively. Thus, patients with advanced Bismuth stage showed a reduced mean survival time, but the difference was not significant. The type of biliary drainage had no significant beneficial effect on the mean survival time (ERC vs PTBD, P = 0.806).

CONCLUSION: Initial bilirubin level is a significant prognostic factor for survival of patients. In contrast, age, tumor stage according to the Bismuth-Corlette classification, and types of intervention are not significant prognostic parameters for survival. Palliative treatment with endoscopic or percutaneous biliary drainage is still suboptimal, new diagnostic and therapeutic tools need to be evaluated.

- Citation: Weber A, Landrock S, Schneider J, Stangl M, Neu B, Born P, Classen M, Rösch T, Schmid RM, Prinz C. Long-term outcome and prognostic factors of patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(9): 1422-1426

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i9/1422.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i9.1422

Hilar cholangiocarinomas (Klatskin-tumors) are classified into 4 stages according to the Bismuth classification: stageI or II for tumors expanding up the hilus, type III A/B infiltrating the right or left hepatic duct, and stage IV with infiltration of both hepatic ducts and subsegments[1]. Epidemiological data reveal an increasing mortality of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Because of the late presentation of symptoms, tumors are usually diagnosed in their later stages, and thus most therapy concepts cannot be curative[2,3]. The prognosis of patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma is poor, and the survival rate reported so far describes a very limited life expectancy < 3 mo if no treatment is offered. Although radical hilar tumor is a formidable challenge for surgeons, endoscopic transpapillary and/or percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage offers the best survival[4,5].

Possible treatment strategies for best supportive care include endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) with transpapillary stent therapy or percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD)[6-8]. Effective endoscopic stent placement provides adequate relief of symptoms associated with biliary obstruction and leads to increased overall survival[9,10]. Systemic chemotherapy, another palliative therapy concept, is marginally effective and dose-limited because of toxic side effects[11]. Unfortunately, the efficacy of percutaneous radiation, brachytherapy or radiochemotherapy is limited[12,13].

In the present study, the clinical outcome of patients with hilar cholangiocarinoma was investigated with regard to possible prognostic factors such as Bismuth stage, bilirubin levels, age, and types of endoscopic intervention. Special attention was given to endoscopic transpapillary versus percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage.

Long-term follow-up of patients with hilar cholangio-carcinoma undergoing endoscopic and/or surgical therapy was performed by retrospective analysis. The study included 96 unselected consecutive patients (56 males and 40 females with a mean age of 67 years) undergoing treatment for hilar cholangiocarinoma from 1995 to 2005 in the Department of Gastroenterology and Surgery at the Technical University Munich. Data acquisition was based on hospital records. Furthermore, follow-up data were obtained by telephone contact with relatives of the patients or referring physicians. In order to evaluate the life expectancy of patients with cholangiocarcinoma, follow-up analysis was done from the time when the patient received his or her first treatment until death. Baseline characteristics were age, gender, bilirubin levels, alkaline phosphatase, γ-GT, leucocytes, and type of therapeutic procedures including endoscopic transpapillary drainage, percutaneous transhepatic drainage and surgery.

The biliary stricture location was classified in relation to the confluence of hepatic ducts as described by Bismuth-Corlette[1]. Bismuth stage was assessed by endoscopic retrograde cholangiography, endoscopic retrograde cholangioscopy, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography and/or percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopy. In addition, selected patients underwent computertomography (CT-scan), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreaticography (MRCP). The final diagnosis was made by surgical specimens, autopsy, percutaneous ultrasound-guided fine needle biopsy, endoscopic ultrasound guided-fine needle biopsy, endoscopic transpapillary forceps biopsy/brush cytology, percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopic guided biopsy, and clinical course.

The type of therapeutic procedures depended on tumor expansion and clinical conditions of patients. If the tumor was resectable, surgery was the first choice of treatment for patients in good clinical conditions. In all patients the possibility of a curative therapy concept with tumor resection was evaluated. In patients with non-resectable tumors or bad clinical conditions, palliative procedure using endoscopic transpapillary and/or percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage was performed. R1-resected patients received also endoscopic and/or percutaneous drainage as a second-line treatment.

ERC was done by a standard videoduodenoscope Olympus TFJ 160-R (Olympus, Hamburg, Germany). The first ERC comprised an endoscopic sphincterotomy (EPT) using an Olympus papillotom (Olympus, Hamburg, Germany) introduced over a Terumo guide wire. Under radiographic guidance using contrast fluid bile duct strictures were localized. Subsequently, one or more plastic endoprotheses were placed above the stricture to obtain biliary drainage. The caliber of stents varied between 7 F and 12 F. Elective stent changes were conducted at a time interval of 3 mo unless the clinical situation of patients required an earlier intervention.

In patients with percutaneous transhepatic drainage the biliary system was punctured with a steel needle, and a nitinol-coated guide wire (35’’) was introduced into the bile duct after contrast visualization of the biliary system. Dilation of the bile duct stricture was carried out using 8 F, 10 F, and 12 F bougies. After a first attempt, a 10 F pigtail catheter was introduced. In a second attempt, bile duct dilatation was continued to allow the placement of a 12 F, 14 F or 16 F Yamakawa drainage. The Yamakawa drainage was changed at a time interval of 3 mo.

Survival curves in relation to bilirubin, Bismuth stage and type of endoscopic procedures (ERC versus PTBD) were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier curves and comparisons were made by using the log rank test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 96 consecutive patients underwent treatment for malignant hilar bile duct tumors during 1995-2005. The characteristics of patients entered into this study included mean age of 67 ± 8.6 years, 9.73 ± 7.1 mg/dL bilirubin, 599 ± 277 U/L alkaline phosphatase L, 373 ± 235 U/L γ-GT, and 9.17 ± 2.75 G/L leucocytes. Of the 96 patients at the time of their initial diagnosis, 10 were diagnosed as Bismuth stage II, 35 as Bismuth stage III, and 51 as Bismuth stage IV. Patients with Bismuth stage I were not identified by endoscopic and percutanoeus procedures. The characteristics of resected and non-resected patients are given in Table 1. A characteristic radiological examination via ERC is shown in Figure 1. The patients presented with jaundice (bilirubin > 10 mg/dL) and almost complete obstruction of the left and right hepatic duct.

| Resection | No resection | Standart values | Scale unit | |

| Number of patients | 20 | 76 | - | - |

| Age (yr) | 62 ± 8.4 | 68 ± 8.3 | - | - |

| Bismuth II | 2 | 8 | - | - |

| Bismuth III | 7 | 28 | - | - |

| Bismuth IV | 11 | 40 | - | - |

| Bilirubin | 5.4 ± 5.28 | 10.87 ± 7.11 | < 1.2 | mg/dL |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 561 ± 278 | 610 ± 275 | 40–120 | U/L |

| γ-GT | 401 ± 225 | 365 ± 237 | < 66 | U/L |

| Leucocytes | 8.95 ± 2.64 | 9.21 ± 2.79 | 4-9 | G/L |

Of the 96 patients 20 were initially treated with surgery. Two of these 20 patients had R0-resection with complete tumor removal, 18 had R1-resection. All the 18 R1-resected patients had recurrent biliary obstruction, thus requiring subsquent endoscopic (ERC) and/or PTBD. Seventy-six out the 96 patients underwent only endoscopic transpapillary (n = 45) and/or percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (n = 31). Figure 2 shows the algorithm of treatment strategies in the resected and endoscopic group. The overall mean survival was 359 ± 296 d in the endoscopic group, 656 ± 299 d in the R0-resected group, and 1114 ± 924 d in the R1-resected group. Due to the small number of resected patients and unbalanced baseline characteristics, a direct comparison of survival time between the endoscopic and resected groups was not carried out.

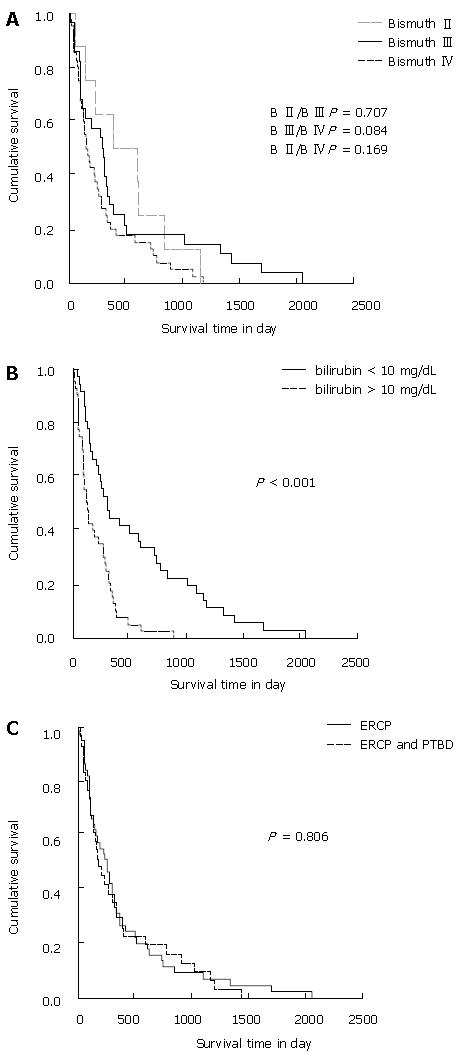

We investigated the correlation of mean survival time and Bismuth stage at the time of initial diagnosis in 76 patients with non-respectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma. The mean survival time of patients with Bismuth stage II (n = 8), III (n = 28) and IV (n = 40) was 496 ± 300 d, 441 ± 385 d and 274 ± 218 d, respectively. The Kaplan-Meier estimate for survival depending on Bismuth stage is shown in Figure 3A. The mean survival time of patients with Bismuth stage II was not significantly higher than that of patients with Bismuth stage III (P = 0.707) or Bismuth IV (P = 0.169). Patients with Bismuth stage III also did not have a significantly longer survival time than patients with Bismuth stage IV (P = 0.084).

The Kaplan-Meier estimate for mean survival depending on serum bilirubin levels at the time of primary diagnosis is shown in Figure 3B. The mean survival time of patients with bilirubin levels < 10 mg/dL (n = 36) was 541 ± 420 d, the mean survival of patients with bilirubin levels > 10 mg/dL (n = 40) was 195 ± 141 d. Thus, in the non-resected group, the mean survival time of patients with initial bilirubin levels > 10 mg/dL was significantly lower (P < 0.001) than that of patients with initial bilirubin levels < 10 mg/dL.

The type of endoscopic procedures had no significant beneficial effect on the mean survival of non-resected patient (Figure 3C). Forty-five patients only treated with endoscopic transpapillary drainage (ERC) had a mean survival time of 381 ± 286 d, and 31 patients who were additionally treated with PTBD had a mean survival time of 368 ± 312 d (P = 0.806).

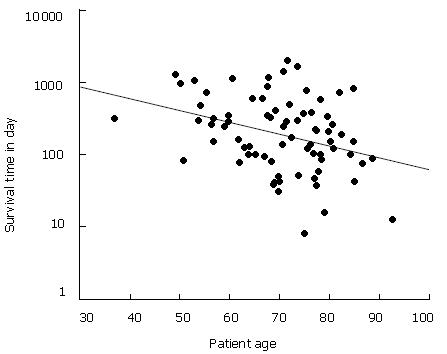

Concerning the age of non-resected patients at the time of primary diagnosis, the mean survival rate appeared to decline with increasing age. The regression line in the scatter plot (Figure 4) showed that life expectancy measured in days was reduced to about 50% between the age of 50 and 80 years at the time of primary diagnosis.

Cholangiocarcinoma is the second most common primary hepatic cancer. Although its overall incidence is low, it is on the rise globally[14]. Risk factors for development of cholangiocarcinoma are liver cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), chronic choledocholithiasis, liver cirrhosis, bile duct adenoma, and other rare diseases such as biliary papillomatosis, Caroli’s disease, choledochal cyst and parasitic biliary infestation and chronic typhoid carrier state[15,16]. However, in the majority of patients with cholangiocarcinoma etiology is unknown. In our cohort only a minority showed risk factors including liver cirrhosis or primary sclerosing cholangitis. Consequently, it remains to be determined what other causes of tumor development play a role in this disease, specially the role of bacterial colonisation, e.g. Helicobacter species that have been previously associated with cholangiocarcinoma formation.

Most commonly, cholestasis occurs in later stages when the bile duct is obstructed in the subhilar or hilar regions. Surgical resection is a mainstay of treatment with curative intent. However, previous reports indicate that not all patients are able to undergo a surgical treatment and thus, palliative options can be offered in a lot of cases[17-19]. In line with these results, in the current retrospective analysis tumour resection was performed only in 20/96 patients. To some extent, surgical procedures have been restricted since R0-resection is hard to achieve and preoperative diagnostic procedure cannot accurately predict stages of tumor extent and infiltration. In our study R0-resection could be achieved in only 2/20 patients. Eighteen of these 20 patients had no complete tumor removal and underwent additional endoscopic and/or percutaneous transhepatic procedures. Of the 96 non-respectable patients, 76 underwent endoscopic and/or percutaneous treatment as the first-line therapy. It has to be mentioned that the decision for surgery was biased in our study since younger patients with lower bilirubin levels were chosen. Nevertheless, our study supported the resection of the tumours even more aggressively, which is consistent with other reports[20,21].

The current study focussed on the long-term outcome of 76 patients with non-resected cholangiocarinoma. Palliative treatment strategies including ERC and PTBD, routinely performed in our hospital, had only few complications and were safe and effective measures to improve excretion of bile fluid. No difference was found in the effectiveness between ERC and PTBD. However, previous reports indicate that PTBD may be superior to ERC[9].

Most important, we found that bilirubin levels at initial diagnosis were a significant prognostic parameter. Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed that bilirubin levels seemed to correlate with the survival time. So far, no other reports have shown this association as clear as in the current study, and thus, this factor needs to be taken into account when initial diagnose is made.

Other groups performed photodynamic therapy (PDT) for bile duct cancer and have achieved survival time of 98 d in the control group treated with endoscopic stenting, and 493 d in the group additionally treated with PDT[22]. Zoepf et al[23] showed that patients not treated with PDT could survive 7 mo, and those treated with PDT could survive 21 mo. In the current study the mean survival time of patients undergoing palliative endoscopic and/or percutaneous drainage was 359 d. Ortner et al[22] showed that the control group has a significant shorter survival time, which is comparable to our results. This may be explained by the lack of adequate bilirubin drop after endoscopic procedures in the control group.

In conclusion, bilirubin level is a significant prognostic factor for the survival of patients. Endoscopic and/or percutaneous biliary drainge represents the mainstream of palliative treatment for patients with non-resectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Although newer treatment modalities such as PDT can improve the expectancy of life, the overall survival is still unsatisfactory. Thus, additional diagnostic and therapeutic strategies should be evaluated.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Zhou T

| 1. | Bismuth H, Castaing D, Traynor O. Resection or palliation: priority of surgery in the treatment of hilar cancer. World J Surg. 1988;12:39-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | de Groen PC, Gores GJ, LaRusso NF, Gunderson LL, Nagorney DM. Biliary tract cancers. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1368-1378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 708] [Cited by in RCA: 682] [Article Influence: 26.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ahrendt SA, Nakeeb A, Pitt HA. Cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Liver Dis. 2001;5:191-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Isa T, Kusano T, Shimoji H, Takeshima Y, Muto Y, Furukawa M. Predictive factors for long-term survival in patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Surg. 2001;181:507-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hanazaki K, Kajikawa S, Shimozawa N, Shimada K, Hiraguri M, Koide N, Adachi W, Amano J. Prognostic factors of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma after hepatic resection: univariate and multivariate analysis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:311-316. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Bismuth H, Nakache R, Diamond T. Management strategies in resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 1992;215:31-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 549] [Cited by in RCA: 512] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Reed DN, Vitale GC, Martin R, Bas H, Wieman TJ, Larson GM, Edwards M, McMasters K. Bile duct carcinoma: trends in treatment in the nineties. Am Surg. 2000;66:711-714; discussion 714-715. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Chamberlain RS, Blumgart LH. Hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a review and commentary. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:55-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Born P, Rösch T, Brühl K, Sandschin W, Weigert N, Ott R, Frimberger E, Allescher HD, Hoffmann W, Neuhaus H. Long-term outcome in patients with advanced hilar bile duct tumors undergoing palliative endoscopic or percutaneous drainage. Z Gastroenterol. 2000;38:483-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liu CL, Lo CM, Lai EC, Fan ST. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic endoprosthesis insertion in patients with Klatskin tumors. Arch Surg. 1998;133:293-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hejna M, Pruckmayer M, Raderer M. The role of chemotherapy and radiation in the management of biliary cancer: a review of the literature. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:977-986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | McMasters KM, Tuttle TM, Leach SD, Rich T, Cleary KR, Evans DB, Curley SA. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation for extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Surg. 1997;174:605-608; discussion 608-609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bowling TE, Galbraith SM, Hatfield AR, Solano J, Spittle MF. A retrospective comparison of endoscopic stenting alone with stenting and radiotherapy in non-resectable cholangiocarcinoma. Gut. 1996;39:852-855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Patel T. Increasing incidence and mortality of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. Hepatology. 2001;33:1353-1357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 773] [Cited by in RCA: 797] [Article Influence: 33.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chapman RW. Risk factors for biliary tract carcinogenesis. Ann Oncol. 1999;10 Suppl 4:308-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Acalovschi M. Cholangiocarcinoma: risk factors, diagnosis and management. Rom J Intern Med. 2004;42:41-58. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Chu KM, Lai EC, Al-Hadeedi S, Arcilla CE, Lo CM, Liu CL, Fan ST, Wong J. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. World J Surg. 1997;21:301-305; discussion 305-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lang H, Sotiropoulos GC, Frühauf NR, Dömland M, Paul A, Kind EM, Malagó M, Broelsch CE. Extended hepatectomy for intrahepatic cholangiocellular carcinoma (ICC): when is it worthwhile? Single center experience with 27 resections in 50 patients over a 5-year period. Ann Surg. 2005;241:134-143. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Witzigmann H, Berr F, Ringel U, Caca K, Uhlmann D, Schoppmeyer K, Tannapfel A, Wittekind C, Mossner J, Hauss J. Surgical and palliative management and outcome in 184 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma: palliative photodynamic therapy plus stenting is comparable to r1/r2 resection. Ann Surg. 2006;244:230-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zervos EE, Pearson H, Durkin AJ, Thometz D, Rosemurgy P, Kelley S, Rosemurgy AS. In-continuity hepatic resection for advanced hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Surg. 2004;188:584-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lygidakis NJ, Sgourakis GJ, Dedemadi GV, Vlachos L, Safioleas M. Long-term results following resectional surgery for Klatskin tumors. A twenty-year personal experience. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:95-101. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Ortner ME, Caca K, Berr F, Liebetruth J, Mansmann U, Huster D, Voderholzer W, Schachschal G, Mössner J, Lochs H. Successful photodynamic therapy for nonresectable cholangiocarcinoma: a randomized prospective study. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1355-1363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 446] [Cited by in RCA: 383] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zoepf T, Jakobs R, Arnold JC, Apel D, Riemann JF. Palliation of nonresectable bile duct cancer: improved survival after photodynamic therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2426-2430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |