Published online Jan 21, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i3.355

Revised: September 30, 2006

Accepted: October 16, 2006

Published online: January 21, 2007

AIM: To investigate the prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotypes in Serbia and Montenegro and their influence on some clinical characteristics in patients with chronic HCV infection.

METHODS: A total of 164 patients was investigated. Complete history, route of infection, assessment of alcohol consumption, an abdominal ultrasound, standard biochemical tests and liver biopsy were done. Gene sequencing of 5’ NTR type-specific PCR or commercial kits was performed for HCV genotyping and subtyping. The SPSS for Windows (version 10.0) was used for univariate regression analysis with further multivariate analysis.

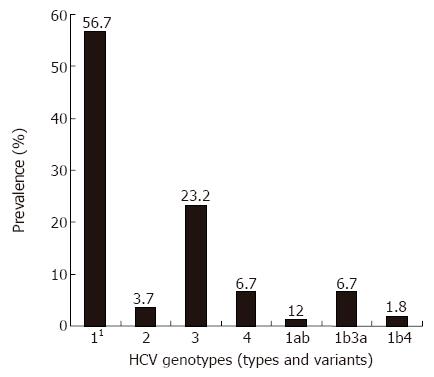

RESULTS: The genotypes 1, 2, 3, 4, 1b3a and 1b4 were present in 57.9%, 3.7%, 23.2%, 6.7%, 6.7% and 1.8% of the patients, respectively. The genotype 1 (mainly the subtype 1b) was found to be independent of age in subjects older than 40 years, high viral load, more severe necro-inflammatory activity, advanced stage of fibrosis, and absence of intravenous drug abuse. The genotype 3a was associated with intravenous drug abuse and the age below 40. Multivariate analysis demonstrated age over 40 and intravenous drug abuse as the positive predictive factors for the genotypes 1b and 3a, respectively.

CONCLUSION: In Serbia and Montenegro, the genotypes 1b and 3a predominate in patients with chronic HCV infection. The subtype 1b is characteristic of older patients, while the genotype 3a is common in drug abusers. Association of the subtype 1b with advanced liver disease, higher viral load and histological activity suggests earlier infection with this genotype and eventually its increased pathogenicity.

- Citation: Svirtlih N, Delic D, Simonovic J, Jevtovic D, Dokic L, Gvozdenovic E, Boricic I, Terzic D, Pavic S, Neskovic G, Zerjav S, Urban V. Hepatitis C virus genotypes in Serbia and Montenegro: The prevalence and clinical significance. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(3): 355-360

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i3/355.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i3.355

Analysis of genome of hepatitis C virus (HCV) isolates from around the world has shown substantial heterogeneity of nucleotide sequences and has identified at least six genotypes[1,2]. The prevalence of HCV genotypes mostly depends on geographic location and for that reason, the genotype identification is crucially important in epidemiological investigation[3]. However, it is thought that HCV genotypes may influence some diversity in liver disease presentation, its outcome and response to antiviral treatment[4].

The aim of our study was to determine the HCV genotype prevalence in this area of the Southeast part of the Balkan and to evaluate the genotype distribution and its association with some clinical characteristics in patients with chronic HCV infection.

We retrospectively studied 164 patients with chronic HCV infection that had been selected for antiviral treatment. Patients were hospitalized in the Institute for Infectious and Tropical Diseases, Department for Viral Hepatitis, from January 1, 2005 to March 31, 2006. Patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), co-infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) were excluded from the study. Complete history with possible route of infection, physical examination, assessment of alcohol consumption, an abdominal ultrasound and standard biochemical liver functional tests were taken in investigated patients. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) values were measured at presentation. Percutaneous liver biopsy was performed in all patients. The hepatic pathology expert assessed histological grades (activity) and stages (fibrosis) with Masson’s trichrome stained tissue specimens, using the Ischak scoring system[5]. In the whole cohort of patients, there were 98 males and 66 females, aged from 16-65 years (mean, 41 ± 12).

For detection of sera specific antibodies to HCV and HIV (anti-HCV, anti-HIV) and surface HBV antigen (HBsAg), commercial kits were used (Ortho EIA; BioRad, ELISA). Quantification of the viral genome (HCV RNA) in sera was done by the amplification method (Amplicor Roche Monitor) and expressed in copies/mL (dividing factor in IU/mL is 2.7). Gene sequencing of 5’ NTR type-specific PCR or commercial kits (InnoLipa, Innogenetics, Genotyping Linear Array hepatitis C virus test, Roche Diagnostics) was performed for HCV genotyping and subtyping.

All tests of association between the genotypes and other parameters were based preferentially on data for the genotypes 1, 3 and 1b3a because only a few patients (less than 5%) had the genotypes 2 and 1b4. Histological scores of activity and fibrosis, viral load, and ALT values were separately divided into two categorical groups in order to evaluate the possible difference in pathogenicity of the genotypes. Activity scores combined necro-inflammatory lesions, periportal necrosis and lobular necrosis were graded as scores ≤ 2 (absent-mild) and scores ≥ 3 (moderate-severe). Fibrosis scores were divided into scores ≤ 3 (absent-moderate) and ≥ 4-6 (severe -cirrhosis). Viral load of HCV RNA was determined as high ≥ 2 × 106 copies/mL. Values of ALT were determined high if they were 2.5 × and 5 × higher than normal values (≤ 41 IU/mL).

The electronic database organized in the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) for Windows (version 10.0) was used. The results are expressed as means ± SD or as percentages. Parametric (Mann-Whitney test, Kruskal-Wallis test) and non-parametric tests (chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test) and the Spearman correlation test were performed to identify significantly different variables that entered into univariate logistical regression analysis with further multivariate analysis. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05 and in the case of multiple testing at P < 0.01. Data is presented with 95% confidence levels.

The most commonly detected genotype in the whole cohort was genotype 1 (57.9%), with the predominant subtype 1b (54.9%). The subtype 1a was detected in one patient (0.6%) only. Genotype 3 was comprised exclusively of the subtype 3a, while genotype 2 comprised the subtypes a, b and c. Mixed inter- genotype infection, such as 1b3a and 1b4 were detected in 13 (8.54%) patients, while mixed intra-genotype infection (1ab) was detected in two (1.2%) patients (Figure 1).

Statistical analysis did not show a difference in the frequency distribution of genotypes according to gender of the patients. The age of the patients was analyzed as a continuous and a categorical variable (< 40 and ≥ 40 years). Result of ages of the patients in detail is presented in Table 1. Significant statistical difference was found between ages of the patients depending on the genotypes (χ2 = 23.474; r = 3; P < 0.001). Patients with genotype 1 (44.31 ± 12) were older than patients with genotypes 3, 4 and 1b3a (37.18 ± 10.02 versus 32 ± 12.59 versus 31 ± 8.73, P < 0.01, P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively). In the whole cohort, approximately a half of the patients (52%) were aged ≥ 40 years. Analyzing the genotypes according to ages over ≥ 40, differences in frequency distribution were found for genotypes 1, 3 and 1b3a (33 versus 25 versus 9, P < 0.01, P < 0.05 and P < 0.05, respectively).

| Genotype | n | Mean ± SD (yr) | Range (yr) |

| 11 | 95 | 44 ± 12 | 21-65 |

| 2 | 6 | 36 ± 13 | 22-51 |

| 3 | 38 | 37 ± 10 | 23-62 |

| 4 | 11 | 32 ± 13 | 16-55 |

| 1b3a | 11 | 31 ± 9 | 18-48 |

| 1b4 | 3 | 42 ± 11 | 33-54 |

| Total | 164 | 41 ± 12 | 16-65 |

Result of univariate logistic analysis of all three genotypes according to age ≥ 40 years is presented in Table 2. Univariate analysis demonstrated independent association of age ≥ 40 years and all three genotypes: 1 (mainly subtype 1b), 3a and 1b3a. Further multivariate analysis revealed only the age ≥ 40 years as the positive predictive factor for the genotype 1 [P < 0.001, Exp (B) = 3.757; 1.952-7.232].

Data about alcohol consumption were available from 161 patients, 30 of them admitted moderate or heavy alcohol abuse (30 g/d or more). There was no statistically significant difference of the frequency distribution of the genotypes according to moderate and/or heavy alcohol consumption.

The possible route of infection was recognized in 98 (59.7%) patients. Among these patients, patients who had a history of intravenous drug use (IVDU), received blood transfusion, had accidental inoculation and/or were undergoing chronic hemodialysis, and healthcare workers, were found in 45.9%, 32.6%, 15.3% and 6.1%, respectively. Statistical analysis showed significant differences in frequency of genotypes 1 and genotype 3 and IVDU (19/95 vs 17/38, P < 0.05 and P < 0.05, respectively). Result of univariate logistic analysis of the genotypes 1 and genotype 3a and IVDU is presented in Table 3. Univariate analysis demonstrated independent association of the IVDU and the genotypes 1 (96.7% subtype 1b) and 3a. Further multivariate analysis revealed IVDU as the positive predictive factor for the genotype 3a [P < 0.01, Exp (B) = 2.833; 318-6.089].

Fibrosis score was assessed in all patients. Score from ≤ 3 and ≥ 4 had 60% and 40% of the patients, respectively. Significant difference was found in the distribution of genotype 1 and fibrosis score ≥ 4 (45 vs 21, P < 0.05). Further univariate logistic analysis showed a fibrosis score ≥ 4 being independent of genotype 1 [P < 0.05, Exp (B) = 2.056; 1.072-3.938]. Histological activity was assessed in 161 patients and scores of ≤ 2, and ≥ 3 were established in 93.1% and 6.8% of patients, respectively. Statistical analysis of frequency in HCV genotype distribution according to activity score ≥ 3 showed a significant difference in frequency of genotype 1 and other genotypes and histological activity (92 vs 69, P < 0.05), and also the positive correlation between these two variables (P < 0.05). But further univariate logistic analysis did not show independent association of genotype 1 and histological activity score ≥ 3.

Values of ALT varied from 11 IU/L to 292 IU/L (mean, 80 ± 53). ALT values 2.5 × and 5 × higher than normal value (102.5 IU/mL; 205 IU/mL) had 22.6% and 3.6% of the patients, respectively. No significant difference was found in the frequency of genotype distribution and the value of ALT 2.5 × higher than normal value.

Viral load was quantified in 126 sera samples. The level of HCV RNA varied from 2000 copies/mL to 31 333 575 copies/mL (mean, 1 694 690 ± 3 284 562). Out of all patients, 27 (21%) had a high level of HCV RNA. Statistically significant difference in frequency of high HCV RNA was found for genotype 1 (96.7% subtype 1b) and other genotypes (23/57 vs 4/42, P < 0.05). A positive correlation was found between genotype 1 and high viral load (P < 0.05), as the univariate logistic analysis also revealed genotype 1 in independent association with high level of HCV RNA [P< 0.05, Exp (B) = 3.819, 1.339-10.89].

Finally, multivariate logistic regression analysis was calculated for genotypes 1 and 3a resulting in significance using univariate analysis. The result of multivariate logistic analysis for genotype 1 is presented in Table 4. The result of multivariate logistic analysis for genotype 3a is presented in Table 5. Accordingly, genotype 1 was demonstrated as significant for the age ≥ 40 years [P= 0.000, Exp (B) = 3.747, 1.952-7.232] whilst the genotype 3a was demonstrated as significant for IVDU [P= 0.008, Exp (B) = 2.833, 1.318-6.089].

The predominating genotype in our study is the genotype 1 (57.9%), mostly the subtype 1b. The genotype 3a is the second most common genotype encountered in 23.2%. The prevalence of HCV genotypes in our investigation is mainly similar to reports of the HCV genotype distribution in other parts of Europe[6-10]. Our current results also confirm findings from Serbia previously published[11,12]. The difference between our result and results from some other European investigators suggests the lower prevalence of the subtype 1a in our cohort that we detected only in one patient. Also, the reported prevalence by other investigators of the genotype 2 particularly in advanced liver disease was more common than we found in our study[13,14]. However, comparison of the prevalence of genotypes between our results and results of other reports also depends on the time of these investigations. In the last decade, a shift in genotype distribution is obvious in many countries, mostly comprising an increase of the prevalence of the genotypes 3a, 1a and 4, and a decrease of the prevalence of genotypes 1b and 2[8,10,14]. The route of HCV transmission mainly causes this epidemiological change in genotype distribution whereas the intravenous drug abuse associated with genotype 3a and 1a has become nowadays the major risk factor of HCV infection[9,10,14-17]. In our investigation, only one patient with genotype 1a cannot confirm this epidemiological shift in IVDU patients of this genotype.

Evaluating the association of the genotypes and demographic data of the patients, we did not find differences in genotype distribution and gender of the patients or alcohol abuse. According to these results, we cannot point out female hormones or moderate to heavy alcohol abuse as participating factors in different disease presentation in association with the genotypes. Conversely, investigation of ages of the patients indicates that older age is strongly associated with the distribution of the genotypes. We found that the genotype 1 was the most common genotype in older patients, while the genotypes 3a, 4 and 1b3a characterized younger patients. Although all three genotypes are independent risk factors for ages over 40, genotype 1 for the age over 40 and genotypes 3a and 1b3a for the patients younger than 40, only the genotype 1 has the predictive importance. According to this finding, we can assume that infection with genotype 1 in this part of Balkan occurred earlier in the past than infection with other genotypes, subtypes and mixed inter-genotype infections, e.g., 4, 3a and 1b3a.

Early investigations from the USA did not find an association between HCV genotypes and mode of transmission[18]. However, the investigators from Europe reported that patients with a history of blood transfusion were mostly infected with genotype 1b while intravenous drug abusers were infected with genotype 3a[7,9,10,15-17,19,20]. Our results show that the genotype 3a is the most important predictive factor for IVDU that is in concordance with these reports. Although we did not confirm correlation of genotype 1b with a mode of HCV transmission, the presence of this genotype as the independent negative risk factor for IVDU may suggest other routes of infection. Additionally, it is possible that relatively high prevalence of mixed inter-genotype infection of 1b3a and 1b4 (8.5%) in our patients can suggest repeated infection in the same persons, although we did not find any association between these genotypes and mode of HCV transmission. Moreover, according to our study, genotype 1 (mostly subtype 1b) is the most common genotype in patients with advanced HCV-related liver disease (fibrosis score equal/higher than 4). We can assume that this association between subtype 1b and more progressive disease is paradigmatic for earlier infection with this subtype in comparison with the subtype 3a and mixed infection with 1b3a. Some previous reports also suggested that subtype 1b is associated with a more advanced stage of liver disease[19,21,22]. Concerning this problem, we must underscore that our cohort was a select group of patients preparing for antiviral treatment. Because of that, patients with end stage liver disease and HCC were excluded from the study. There is a probability that inclusion of these patients may give a more convincing association between the genotypes and the stage of the HCV-related disease.

However, our result of the association of the HCV genotype 1 with a high level of HCV RNA and higher histological activity suggests possible increased pathogenicity of this particular genotype. Although many authors did not confirm this association, some of them suggested similar findings as we did[13,18,19,23]. We must remember again that our study was a cross-sectional and retrospective investigation, and that the factor of time was not taken into account. In any case, our findings that genotype 1b is characterized with a higher level of RNA, in correlation with increased necro-inflammatory changes in the liver than other genotypes, although lack of an increase in biochemical activity could not be ignored as a possible indicator for increased pathogenicity of subtype 1b. Certainly, association between genotypes and the level of HCV RNA and necro-inflammatory activity may need to be investigated in future studies.

Finally, we can conclude that genotype 1, particularly the subtype 1b in older patients with chronic HCV infection, predominates in this geographic Southeast part of the Balkan. The second common prevalence of genotype 3, subtype 3a in younger patients, suggests the increased number of IVDU as the main mode of HCV transmission. The role of subtype 1b that correlates with high viral load and higher histological activity could indicate potentially more pathogenicity of this subtype with consequences such as longer persistence and more aggressive influence in disease outcome that requires careful analysis in prospective setting.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) represents a cause of chronic liver disease that may progress to cirrhosis with serious consequences. Analysis of the HCV genome demonstrated its high heterogeneity and identified at least six different genotypes divided into several subtypes that have epidemiological and clinical importance.

Important areas in investigation of HCV-related chronic liver diseases are identifying infected persons, recognize the route of its transmission, evaluation of the stage of the disease, use of antiviral therapy and prevention measures.

Prevalence of different HCV genotypes and subtypes and their influence on some clinical characteristics in the Southern part of the Balkan was investigated in 164 patients with chronic hepatitis C. The most common genotype is 1 (57.9%), mainly subtype 1b. Genotype 3 (3a) is the second most common genotype, whilst genotypes 1a and 2 are less common than in other European countries. Genotypes 1 and 3a were found as predicting factors for older age and IVDU, respectively.

Actual epidemiologic study of HCV genotypes in specific areas is present in the article. Additionally, different genotypes were related to age, gender, alcohol abuse, route of transmission, biochemical activity, histological findings and viral load. Eventual shifts in the correlation data will be recognized in the future.

HCV is a distinct member of the family Flaviviridae and placed into a separate genus, named Hepacivirus. Genotypes and subtypes of HCV represent its extensive genetic heterogeneity. Genotypes depend mainly on the geographic location and are classified into six main groups, designated as genotypes 1 to 6, with further subdivision within each genotype (a, b, c, etc.). It has been reported that genotypes differ in the severity of the liver disease they cause, baseline of serum RNA levels, response to antiviral treatment and route of transmission.

This article is an essentially confirmatory paper of the previously published observation on the genotype distribution in Serbia, particularly the confirmation of an unusual high prevalence of mixed genotype infection (about 8%-9% in the two papers). The finding of higher HCV RNA levels in genotype 1b is contradicted in most literature and the claim that genotype 1b had higher pathogenicity cannot be substantiated, unless in a prospective setting.

S- Editor Pan BR L- Editor Alpini GD E- Editor Bi L

| 1. | Choo QL, Richman KH, Han JH, Berger K, Lee C, Dong C, Gallegos C, Coit D, Medina-Selby R, Barr PJ. Genetic organization and diversity of the hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2451-2455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1133] [Cited by in RCA: 1131] [Article Influence: 33.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Simmonds P, Smith DB, McOmish F, Yap PL, Kolberg J, Urdea MS, Holmes EC. Identification of genotypes of hepatitis C virus by sequence comparisons in the core, E1 and NS-5 regions. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:1053-1061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Simmonds P. Genetic diversity and evolution of hepatitis C virus--15 years on. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:3173-3188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 622] [Cited by in RCA: 632] [Article Influence: 30.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zein NN. Clinical significance of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:223-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, Callea F, De Groote J, Gudat F, Denk H, Desmet V, Korb G, MacSween RN. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1995;22:696-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3521] [Cited by in RCA: 3779] [Article Influence: 126.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Pawlotsky JM, Tsakiris L, Roudot-Thoraval F, Pellet C, Stuyver L, Duval J, Dhumeaux D. Relationship between hepatitis C virus genotypes and sources of infection in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1607-1610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kleter B, Brouwer JT, Nevens F, van Doorn LJ, Elewaut A, Versieck J, Michielsen PP, Hautekeete ML, Chamuleau RA, Brénard R. Hepatitis C virus genotypes: epidemiological and clinical associations. Benelux Study Group on Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C. Liver. 1998;18:32-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ross RS, Viazov S, Renzing-Köhler K, Roggendorf M. Changes in the epidemiology of hepatitis C infection in Germany: shift in the predominance of hepatitis C subtypes. J Med Virol. 2000;60:122-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Elghouzzi MH, Bouchardeau F, Pillonel J, Boiret E, Tirtaine C, Barlet V, Moncharmont P, Maisonneuve P, du Puy-Montbrun MC, Lyon-Caen D. Hepatitis C virus: routes of infection and genotypes in a cohort of anti-HCV-positive French blood donors. Vox Sang. 2000;79:138-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Savvas SP, Koskinas J, Sinani C, Hadziyannis A, Spanou F, Hadziyannis SJ. Changes in epidemiological patterns of HCV infection and their impact on liver disease over the last 20 years in Greece. J Viral Hepat. 2005;12:551-557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Stamenkovic G, Zerjav S, Velickovic ZM, Krtolica K, Samardzija VL, Jemuovic L, Nozic D, Dimitrijevic B. Distribution of HCV genotypes among risk groups in Serbia. Eur J Epidemiol. 2000;16:949-954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hozić D, Stamenković G, Bojić I, Dimitrijević J, Krstić L. Role of various virus genotypes in progression of chronic hepatitis C. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2002;59:141-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fattovich G, Ribero ML, Pantalena M, Diodati G, Almasio P, Nevens F, Tremolada F, Degos F, Rai J, Solinas A. Hepatitis C virus genotypes: distribution and clinical significance in patients with cirrhosis type C seen at tertiary referral centres in Europe. J Viral Hepat. 2001;8:206-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Payan C, Roudot-Thoraval F, Marcellin P, Bled N, Duverlie G, Fouchard-Hubert I, Trimoulet P, Couzigou P, Cointe D, Chaput C. Changing of hepatitis C virus genotype patterns in France at the beginning of the third millenium: The GEMHEP GenoCII Study. J Viral Hepat. 2005;12:405-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Dal Molin G, Ansaldi F, Biagi C, D'Agaro P, Comar M, Crocè L, Tiribelli C, Campello C. Changing molecular epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection in Northeast Italy. J Med Virol. 2002;68:352-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kalinina O, Norder H, Vetrov T, Zhdanov K, Barzunova M, Plotnikova V, Mukomolov S, Magnius LO. Shift in predominating subtype of HCV from 1b to 3a in St. Petersburg mediated by increase in injecting drug use. J Med Virol. 2001;65:517-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Balogun MA, Laurichesse H, Ramsay ME, Sellwood J, Westmoreland D, Paver WK, Pugh SF, Zuckerman M, Pillay D, Wreghitt T. Risk factors, clinical features and genotype distribution of diagnosed hepatitis C virus infections: a pilot for a sentinel laboratory-based surveillance. Commun Dis Public Health. 2003;6:34-39. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Zein NN, Rakela J, Krawitt EL, Reddy KR, Tominaga T, Persing DH. Hepatitis C virus genotypes in the United States: epidemiology, pathogenicity, and response to interferon therapy. Collaborative Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:634-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Vince A, Palmović D, Kutela N, Sonicky Z, Jeren T, Radovani M. HCV genotypes in patients with chronic hepatitis C in Croatia. Infection. 1998;26:173-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Serra MA, Rodríguez F, del Olmo JA, Escudero A, Rodrigo JM. Influence of age and date of infection on distribution of hepatitis C virus genotypes and fibrosis stage. J Viral Hepat. 2003;10:183-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Cathomas G, McGandy CE, Terracciano LM, Gudat F, Bianchi L. Detection and typing of hepatitis C RNA in liver biopsies and its relation to histopathology. Virchows Arch. 1996;429:353-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Pozzato G, Kaneko S, Moretti M, Crocè LS, Franzin F, Unoura M, Bercich L, Tiribelli C, Crovatto M, Santini G. Different genotypes of hepatitis C virus are associated with different severity of chronic liver disease. J Med Virol. 1994;43:291-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sagnelli E, Coppola N, Scolastico C, Mogavero AR, Filippini P, Piccinino F. HCV genotype and "silent" HBV coinfection: two main risk factors for a more severe liver disease. J Med Virol. 2001;64:350-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |