Published online Jul 21, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i27.3767

Revised: April 10, 2007

Accepted: April 16, 2007

Published online: July 21, 2007

A 31-year-old female who had well-established polycythemia vera one year before, presented with the sudden onset. She had severe ascites and hepatic encephalopathy 12 d prior to admission. Real-time ultrasonography revealed a supra hepatic thrombosis extending toward the inferior vena cava (lVC). Thrombolytic therapy with systemic streptokinase (250 000 IU loading + 100 000 IU/h infusion) was started. At the end of 72 h infusion, the patient's general condition improved. A color Doppler ultrasonography then showed complete and partial resolution of the thrombosis in the supra hepatic vein and IVC, respectively. Despite this good response, 12 d later, the symptoms recurred. Venography detected complete obstruction of the lVC. Percutanous balloon angioplasty with stent insertion was performed successfully and the patient was discharged without any evidence of liver disease. A combination of systemic streptokinase and radiological intervention was effective in our patient.

- Citation: Reza F, Naser DE, Hossein G, Mehrdad Z. Combination of thrombolytic therapy and angioplastic stent insertion in a patient with Budd-Chiari syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(27): 3767-3769

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i27/3767.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i27.3767

Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS) is a rare entity caused by the obstruction, usually thrombotic in origin, of the hepatic venous outflow[1]. It may be a result of various etiologies including myeloproliferative disorders (polycythemia rubra vera, chronic myelogenous leukemia, essential thrombocythemia, agnogenic myeloid metaplasia), malignancies, infections and benign hepatic lesions, oral contraceptives, pregnancy and other hypercoagulability, states. It usually involves one, two or all the three major hepatic veins with or without extension of the thrombus into the inferior vena cava (IVC). The syndrome may presents with acute (sometimes fulminant), subacute or chronic signs and symptoms of abdominal pain, hepatomegaly, ascites, the lower extremities edema, and venous collateral formation. Without treatment, patients often die primarily of progressive liver failure from chronic hepatic congestion[2].

So far, different therapeutic modalities have been suggested. These include medical treatments (supportive measures, anticoagulants, and thrombolytics), radiological procedures e.g., angioplasty, trans-jugular intrahepatic portacaval shunt (TIPS) and stenting, and surgical interventions (shunting procedures and liver transplantation). There are only few reports of success following conventional treatments such as anticoagulants and diuretics. Radiological procedures and surgical interventions are the most effective treatments recommended for BCS. These include angioplasty, stenting, open endvenectomy[3], shunt and TIPS operations, and more recently, liver transplantation[2].

Fibrinolytic therapy should be restricted to acute or subacute conditions when the formed thrombus is young enough to be resolved by thrombolytic therapy[1].

In this report, we present a patient with BCS who was treated successfully with a combination of thrombolytic therapy and angioplasty with stent insertion.

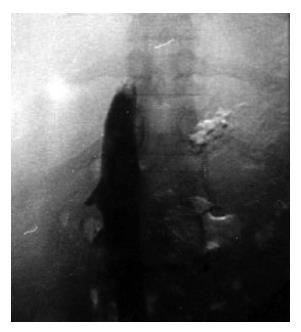

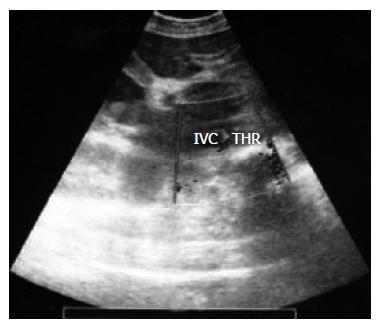

A 31-year-old woman, with a one-year history of polycythemia vera was admitted to our center for a progressive abdominal distension, right upper quadrant abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting for 12-15 d. On physical examination, a massive ascites, pitting edema of the lower extremities and hepatosplenomegaly were evident. Based on the laboratory findings (Table 1), the patient was diagnosed as having stage II hepatic encephalopathy. Real-time ultrasonography, color Doppler and Venography of abdominal veins showed a thrombosis in the hepatic vein and IVC, 5 cm proximal to the hepatic vein junction, deteriorating the blood flow of the portal vein and IVC (Figures 1 and 2). The renal vein was normal. The hepatic and splenic longitudinal diameters were 20 and 16 cm, respectively. The urinary output was slightly low < 400 mL/24 h. All these findings were clearly in favor of an acute BCS. The initial treatment was systemic streptokinase at a loading dose of 250 000 IU for 30 min, followed by a maintenance dose of 100 000 IU/h for 72 h. She also received the standard treatment for encephalopathy. Streptokinase therapy increased the urinary flow to 35 mL/h and reduced both the ascites and the liver size. After four days, the hepatic encephalopathy subsided completely.

| Day of submission | ||||

| 1st | 2nd | 4th | 10th | |

| WBC (/mm3) | 18 000 | 16 500 | 14 300 | 8000 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 19 | 16 | 12 | 11.5 |

| Plt (/mm3) | 421 000 | 410 000 | 380 000 | 275 000 |

| Cr (mg/dL) | 2 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.3 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 29 | 25 | 27 | 18 |

| ALT (U/L) | 101 | 84 | 61 | 22 |

| AST (U/L) | 165 | 127 | 87 | 39 |

| ALP (U/L) | 315 | 229 | 218 | - |

| BLT (T) (mg/dL) | 3.7 | - | - | 1.8 |

| BLT (D) (mg/dL) | 1.9 | - | - | 0.45 |

| PT1 (s) | 20 | 19 | 15 | 222 |

| PTT (s) | 55 | 50 | 49 | 45 |

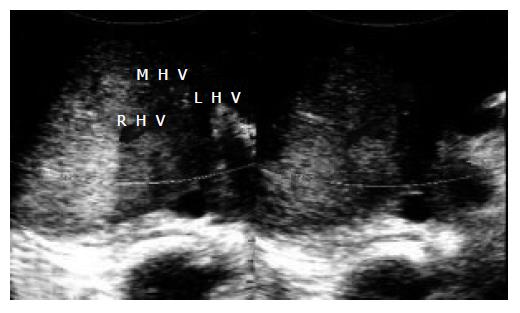

During the thrombolytic therapy, the serum fibrinogen level was measured every 12 h, which ranged between 160 and 200 mg/dL. After completion of thrombolytic therapy (on the third day), Doppler ultrasonography showed an acceptable patency of both IVC and hepatic vein due to complete resolution of the thrombi (Figure 3). Thereafter, the standard anticoagulant therapy was started. The patient was heparinized first and followed by administration of warfarin for attaining a target international normalization ratio (INR) of 2 to 3. To maintain a hemoglobin level < 12 g/dL, 1000 mg/d hydroxyurea along with repeated aggressive phlebotomy was administered from the first day. The patient's weight and abdominal distension gradually reduced until the 15th d after admission.

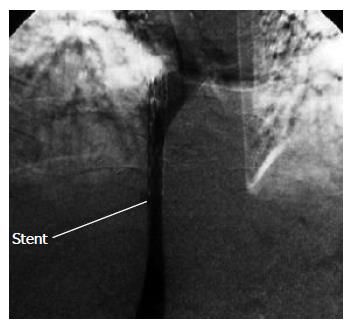

After two weeks, the abdominal pain and a progressive ascites recurred unexpectedly. Venography showed a 5-cm thrombus located in the IVC, proximal to the hepatic vein. The hepatic venous flow was minimal, yet no thrombosis was observed. After percutanous transluminal balloon angioplasty (PTA) was performed, the blood flow of the IVC was restored. However, over the next 48 h, the flow decreased and recurrent stenosis made it necessary to repeat PTA with insertion of a wall stent in the IVC (Figure 4). Two wall stents were placed in the IVC. Color Doppler ultrasonography after stenting showed a complete flow with good patency of both the hepatic vein and IVC. The patient was kept under close observation during the early post-intervention period. Over the next 48 h, the patient's symptoms subsided, the urinary output increased, and the abdominal girth returned to normal. The anticoagulant therapy was instituted. ASA 325 mg/d was added after the stent insertion. Five days after the intervention, the laboratory tests revealed WBC: 11 000/mm3, Hb: 12.5 g/dL, serum creatinine: 1.2 mg/dL, BUN: 23 mg/dL, ALT: 19 IU/L, AST; 25 IU/L, a total serum billirubin level; 0.6 (direct = 0.2) mg/dL, PTT: 40 s, and INR: 2 (PT = 20 s). After one year at follow-up, the patient's status was satisfactory and the hepatic vein and IVC blood flow was complete as assessed by color Doppler ultrasonography at each visit.

Budd-Chiari syndrome can be defined as any patho-physiologic process resulting in interruption or diminution of the normal blood flow out of the liver. If left untreated, it is almost always lethal of progressive liver failure due to chronic hepatic congestion. Medical treatment with diuretics controls the ascites. However, it just provides symptomatic relief. Radiological interventions and surgical approaches to address the underlying etiology are the best treatment to restore the hepatic venous flow[2]. A variety of non-medical approaches have been proposed. Currently, invasive methods like meso-caval or meso-arterial shunting, angioplasty, either alone or in combination with stenting and TIPS, are accepted as standard treatments for BCS. They, however, cannot be employed under certain circumstances, such as severe hepatocellular damage, seriously ill patients or those with extensive thrombosis.

Angioplasty with or without stent insertion is the treatment of choice for many acute cases of BCS involving the IVC. In this technique, the length of thrombosis is an important limiting factor[4]. Due to recurrent stenosis following percutaneous balloon angioplasty, it is necessary to utilize wall stents in many cases. However, further evaluations are required to watch for the intimal fibrosis and subsequent obliteration of the wall stent.

While the conventional anti-coagulation therapy has been poorly effective with the 5-year venous patency of only 10%, the thrombolytic therapy with rTPA, urokinase, or streptokinase is recently reported to be promisingl[5-7]. Sholar et al[8] reported two cases of BCS due to paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria that were successfully treated with streptokinase. In another report, seven patients with hepatic vein and vena caval thrombosis plus disturbed hepatic function were treated with streptokinase. The treatment was successful in four patients with no recurrence[9]. The successful treatment of two children with BCS by this method has also been reported[10]. Although, thrombolytic therapy is used mainly in acute phase of the disease, it may be used as a temporary treatment either to improve the condition of seriously ill patients awaiting surgery, or to reduce the length of the thrombus while preparing the patient for angioplasty and stent insertion. In conclusion, a combination of thrombolytic therapy and angioplasty with wall stent insertion might be beneficial to the patients in the acute phase of BCS. Nevertheless, more investigations are required to evaluate its definite effectiveness and safety.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Lu W

| 1. | Hemming AW, Langer B, Greig P, Taylor BR, Adams R, Heathcote EJ. Treatment of Budd-Chiari syndrome with portosystemic shunt or liver transplantation. Am J Surg. 1996;171:176-180; discussion 180-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Emre A, Kalayci G, Ozden I, Bilge O, Acarli K, Kaymakoğlu S, Rozanes I, Okten A, Tekant Y, Alper A. Mesoatrial shunt in Budd-Chiari syndrome. Am J Surg. 2000;179:304-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Koja K, Kusaba A, Kuniyoshi Y, Iha K, Akasaki M, Miyagi K. Radical open endvenectomy with autologous pericardial patch graft for correction of Budd-Chiari syndrome. Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;4:500-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ishiguchi T, Fukatsu H, Itoh S, Shimamoto K, Sakuma S. Budd-Chiari syndrome with long segmental inferior vena cava obstruction: treatment with thrombolysis, angioplasty, and intravascular stents. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1992;3:421-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bell WR, Meek AG. Current concepts: guidelines for the use of thrombolytic agents. N Engl J Med. 1979;301:1266-1270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Greenwood LH, Yrizarry JM, Hallett JW, Scoville GS. Urokinase treatment of Budd-Chiari syndrome. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1983;141:1057-1059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | McKee CM, Mayne EE, Crothers JG, Callender ME. Budd-Chiari syndrome treated with acylated streptokinase-plasminogen complex. J R Soc Med. 1985;78:768-769. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Sholar PW, Bell WR. Thrombolytic therapy for inferior vena cava thrombosis in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103:539-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pawlak J, Palester-Chlebowczyk M, Michałowicz B, Elwertowski M, Małkowski P, Szczerbień J. Thrombolytic treatment of Budd-Chiari syndrome with portal venous thrombosis. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 1993;89:171-177. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Sawamura R, Fernandes MI, Galvão LC, Goldani HA. Report of two cases of children with Budd-Chiari syndrome successfully treated with streptokinase. Arq Gastroenterol. 1996;33:179-181. [PubMed] |