Published online Jul 21, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i27.3756

Revised: April 10, 2007

Accepted: April 16, 2007

Published online: July 21, 2007

Acute pancreatitis constitutes 3% of all admissions with abdominal pain. There are reports of osteal fat necrosis leading to periosteal reactions and osteolytic lesions following severe pancreatitis, particularly in long bones. A 54-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with acute pancretitis, who later developed spinal discitis secondary to necrotizing pancreatitis. He was treated conservatively with antibiotics and after a month he recovered completely without any neurological deficit. This case is reported for its unusual and unreported spinal complications after acute pancreatitis.

- Citation: Muthukumarasamy G, Shanmugam V, Yule S, Ravindran R. An unreported complication of acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(27): 3756-3757

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i27/3756.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i27.3756

Acute pancreatitis constitutes 3% of all admissions with abdominal pain[1]. The majority of cases are mild and self-limiting. However, severe pancreatitis is associated with high morbidity and mortality and affects almost all the organs in the body. The involvement of the skeletal system has been reported after an attack of acute pancreatitis[2,3]. There are reports of osteal fat necrosis leading to periosteal reactions and osteolytic lesions following pancreatitis, particularly common in long bones[2,4]. Nevertheless, pyogenic spinal osteomyelitis in association with pancreatitis is rarely reported[5]. We present one of the rare complications of acute necrotizing pancreatitis, the spinal discitis.

A 54-year-old male chronic alcoholic patient with vomiting and abdominal pain was referred by his general practitioner (GP) to the general surgical emergency ward. The referring doctor recorded a pulse rate of 120/min and blood pressure of 220/130 mmHg. There was no relevant past medical history except recent diagnosis of reflux oesophagitis. The patient was not on any regular medications. Clinical examination revealed diffuse abdominal tenderness and guarding (serum amylase, 1150 U/L; CRP, 180 mg/L). A provisional diagnosis of acute alcoholic pancreatitis was made and managed symptomatically. Three days later, the patient discharged himself against medical advice.

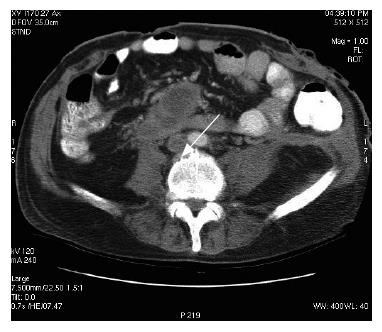

The next day, he was re-referred by his GP with abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhoea, and malena. His vitals showed tachycardia and tachypnoea. He was flushed and his abdomen distended with diffuse tenderness and guarding. Glasgow severity score for pancreatitis was 3 at this point. Computerized tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen showed extensive pancreatic necrosis with peri-pancreatic fluid collection (15 cm × 13.3 cm) and bilateral pleural effusions. There were no radiological signs of peri-pancreatic infection. Two weeks later, he developed vomiting with pyrexia; white cell count (20.9 × 109/L) and C-reactive protein were elevated (239 mg/L), and haemoglobin dropped from 157 to 91 mg/L. Abdomen was more distended with diffuse tenderness. Ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration of peri-pancreatic collection revealed gram-positive cocci on microscopic examination. Laparotomy, necrosectomy and debridement of peri-pancreatic area were performed and the abdominal wound closed 48 h later, after lateral relaxing skin incision. Post-operatively, the patient was managed in the intensive therapy unit (ITU) for cardiac and respiratory support. His postoperative recovery was eventful; complicated by renal failure (requiring renal support), left sided cerebral infarct, respiratory failure, candidaemia, staphylococcal septicaemia and pulmonary embolism from ilio-femoral deep venous thrombosis (optease vena cava filter deployed). Persistent pyrexia and imaging evidence of recurrent pancreatic abscess lead to open drainage through a left lumbar incision. Nearly a month later he developed back pain. Clinical examination did not reveal any obvious spinal pathology. X-ray of the lumbar spine demonstrated loss of lordosis and decreased inter-vertebral disc heights at L3/4 and L4/5 with associated sclerosis and osteophytosis. However, there was no collapse of vertebral bodies. A radiological diagnosis of degenerative change was made, and managed symptomatically after appropriate orthopaedic advice. Follow-up CT scan of the abdomen after a month demonstrated irregularity of the end plates of L2/3 with a small but definite fluid collection surrounding the anterior aspect of this inter-vertebral disc, raising the strong suspicion of infective discitis (Figures 1 and 2). The patient was managed conservatively with antibiotics without any residual deformity.

Recent radioactive bone scan revealed no evidence of active infection. On clinical examination, he completely recovered (without neurological deficit) except for occasional back pain and an incisional hernia.

Metastatic fat necrosis following an episode of pancreatitis or pancreatic carcinoma in adults is a well-known entity and reported to manifest in long bones, pericardium, mediastinal fat and subcutaneous tissue[2,4,6]. Two types of bone lesions were described. The first type produces multiple osteolytic lesions and periosteal reaction with intramedullary fat necrosis; the second type is the result of bone infarction. Neuer et al[7] reported a case of osteolytic lesions in a 3-year-old child after traumatic pancreatitis. However, the exact mechanism for these bony lesions is unclear. Circulating pancreatic enzymes (trypsin, elastase, lipase and collagenase) have been implicated as the causation for the intramedullary fat necrosis[2]. Perry, from his rat experiment, demonstrated lymphatic transport of free enzymes resulted in metastatic fat necrosis[3]. This was hypothesized as the mechanism for metastatic ischaemic lesions noticed in pancreatitis. Shinowara et al[8] had proposed the possibility of ischaemic necrosis caused by occlusion of end arteries due to intravascular thrombosis in pancreatitis. Another possible explanation, particularly for spinal osteomyelitis, is that the inflamed pancreas might produce local tissue ischaemia, predisposing to lower thoracic or upper lumbar osteomyelitis due to the close proximity of pancreas to these structures[9].

So far, there has been no reported evidence of spinal discitis following an episode of pancreatitis. Glassman et al[5] have published a case of pyogenic osteomyelitis associated with a previous history of pancreatitis. However, no concurrent spinal disease and pancreatitis was established. They raised the suspicion of bacterial septicaemia, as a complication of pancreatitis, and as the cause of spinal osteomyelitis. In our report, the patient was proved to have definite clinical, radiological and bacteriological evidence of pancreatitis and septicaemia. This correlates well with pancreatitis as the cause for spinal disease. Though the mechanism of involvement of spinal vertebrae in our patients was not clear, the different possibilities including direct spread of infection or chemical soft tissue destruction (because of the closeness of lesion to pancreas) or from metastatic involvement (septicaemia), can be considered. This case was presented for its unusual and unreported spinal complications after acute pancreatitis.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Lu W

| 1. | de Dombal F. The acute abdomen: definitions, diseases ans decisions. 2ed. London: Churchill Livingston 1991; . |

| 2. | Sperling MA. Bone lesions in pancreatitis. Australas Ann Med. 1968;17:334-340. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Achord JL, Gerle RD. Bone lesions in pancreatitis. Am J Dig Dis. 1966;11:453-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wallner B, Friedrich JM, Pietrzyk C. Bone lesions in chronic pancreatitis. Rofo. 1988;149:289-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Glassman SD, Shields CB, Melo JC, Johnson JR, Puno RM. Pyogenic infections of the spine. J Ky Med Assoc. 1992;90:374-379. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Bennett RG, Petrozzi JW. Nodular subcutaneous fat necrosis. A manifestation of silent pancreatitis. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:896-898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Neuer FS, Roberts FF, McCarthy V. Osteolytic lesions following traumatic pancreatitis. Am J Dis Child. 1977;131:738-740. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Shinowara GY, Stutman LJ, Walters MI, Ruth ME, Walker EJ. Hypercoagulability in acute pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1963;105:714-719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kortas DY, Gates LK. Vertebral osteomyelitis mimicking chronic pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:1527-1529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |