Published online Jul 7, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i25.3417

Revised: March 10, 2007

Accepted: March 12, 2007

Published online: July 7, 2007

The purpose of this work was to assess the evidence for effectiveness of acupuncture (AC) treatment in gastrointestinal diseases. A systematic review of the Medline-cited literature for clinical trials was performed up to May 2006. Controlled trials assessing acupuncture point stimulation for patients with gastrointestinal diseases were considered for inclusion. The search identified 18 relevant trials meeting the inclusion criteria. Two irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) trials, 1 Crohn's disease and 1 colitis ulcerosa trial had a robust random controlled trial (RCT) design. In regard to other gastrointestinal disorders, study quality was poor. In all trials, quality of life (QoL) improved significantly independently from the kind of acupuncture, real or sham. Real AC was significantly superior to sham acupuncture with regard to disease activity scores in the Crohn and Colitis trials. Efficacy of acupuncture related to QoL in IBS may be explained by unspecific effects. This is the same for QoL in inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), whereas specific acupuncture effects may be found in clinical scores. Further trials for IBDs and in particular for all other gastrointestinal disorders would be necessary to evaluate the efficacy of acupuncture treatment. However, it must be discussed on what terms patients benefit when this harmless and obviously powerful therapy with regard to QoL is demystified by further placebo controlled trials.

- Citation: Schneider A, Streitberger K, Joos S. Acupuncture treatment in gastrointestinal diseases: A systematic review. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(25): 3417-3424

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i25/3417.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i25.3417

Complementary medicine is increasingly used in numerous diseases[1], also in gastrointestinal disorders[2]. In particular, acupuncture (AC) has become increasingly recognized[3], which might be due to various reasons. Firstly, frequent diseases like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) still lack an effective drug treatment, while complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) offers treatment options for suffering patients[4]. Secondly, many patients are afraid of harmful side effects of conventional treatment, thus searching for harmless treatment options such as acupuncture[5,6]. Furthermore, many patients seek additional CAM therapies as they feel their health related quality of life (QoL) to be improved when treatment strategies are embedded in holistic concepts[7]. Due to patients' demand a number of experimental and clinical studies evaluating acupuncture effects in gastrointestinal disorders were investigated in the last years. Experimental trials indicate some impact of acupuncture on the gastrointestinal system[3,8]. For example, a pain reducing effect during colonoscopy[9] or gastroscopy[10] was demonstrated. Effects were also found in experimental settings for visceral reflex activity[11] and acid secretion in the stomach[12]. However, in contrast to these numerous experimental trials, there are only a few clinical trials which evaluated the efficacy of acupuncture on gastrointestinal disorders. The aim of this systematic review was to evaluate the clinical evidence for the effectiveness of acupuncture on gastrointestinal disorders. Especially QoL improvement will be addressed as it is a main concern for patients seeking CAM therapies for their illnesses that are often difficult to treat.

A literature search was conducted using the MEDLINE database (up to May 2006) using the MESH headings "Gastrointestinal Diseases" and "Acupuncture". Furthermore, a combination of the search terms "gastroint*" and "acupuncture" was used. The search was limited to clinical studies. The bibliographies of all review articles and all included studies were manually searched to identify other potential studies.

As only very few randomised controlled trials in the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders with acupuncture exist, we aimed to include also non-randomised and/or non-controlled trials to ensure a broad overview about acupuncture research in gastrointestinal disorders. All articles that reported a clinical trial in which patients with gastrointestinal disorders were treated with acupuncture point stimulation were included. Publications not presenting the full report of a clinical trial (letters, comments, congress abstracts and editorials) as well as non-English/German/French articles were excluded.

In general, the statistical quality of the trials as well as the technical quality of acupuncture performance improved in the last 10 to 15 years. In particular, quality requirements for an optimal acupuncture treatment and control group remain to discuss. The rules of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) are best met with individual therapeutic schemes (= individual AC). Therefore, individual treatment according to 'patterns of disease' [13] could serve as a gold standard'. However, this is often not practical due to methodological reasons, e.g. an individualised acupuncture could reduce the statistical comparability between groups and could enhance placebo effects by amplifying patient-doctor interactions. As a consequence, some authors choose a fixed AC regime according to a TCM pattern (= standardised AC). Lowest technical acupuncture performance is given if only one acupuncture point is used as this is mostly far away from conceptual TCM frameworks of internal diseases[14,15].

Another challenge is the development of an optimal control procedure in acupuncture trials. As the acupuncturist always knows if real or placebo/sham acupuncture is performed it is impossible to establish double blind acupuncture trials. Several attempts exist to establish control groups. Sham or placebo acupuncture is most commonly used. Acupuncture treatment at non-acupuncture points, ideally with very thin needles usually is labelled as sham acupuncture. Another method of placebo control is established with a blunted telescopic placebo needle which does not penetrate the skin, developed by Streitberger et al[16], or a similarly device of Park et al[17]. The advantage is that it avoids unspecific physiological effects provoked by penetrating the skin, especially if used at non-acupuncture points to avoid potential acupressure effects. However, in case real acupuncture is superior to the placebo-needle, it remains unclear if acupuncture point specificity exists. For example, if there is an improvement in both groups without any group difference, strong unspecific psychological effects may be responsible. Consequently, acupuncture point specificity is only proven when AC is superior to sham acupuncture penetrating the skin. Therefore, each kind of sham/placebo acupuncture allows different conclusions about acupuncture effects and specificity of acupuncture points. To avoid confusion in further reading, we label acupuncture with normal needles at non-acupuncture points as "penetrating sham acupuncture"(p-SAC); acupuncture with telescopic needle is labelled as "non-penetrating sham acupuncture"(np-SAC) due to the conceptualisation of White et al[18].

Other possibilities for placebo controls are given by switched-off laser acupuncture or switched-off transcutaneous electric nervous stimulation (TENS)-device. However, these controls appear to be artificial and not similar enough to real acupuncture treatment. Due to the broad variety of modes of acupuncture treatment and placebo control, both-real and sham/placebo treatment of each trial-are described in Table 1.

| Disease | Reference | Study Design | Treatment | n | Duration of treatment | Primary outcome | Results | Major deficits |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | Schneider et al[22], 2005 | RCT longitudinal evaluation | Standard AC vs np-SAC at non-AP-points | 22 AC 21 np-SAC | 10 sessions, 2 sessions per week | Quality of life | ↑in both groups no significant group difference | Standard AC, no individual AC pattern; Target number not reached |

| Forbes et al[19], 2005 | RCT longitudinal evaluation | Individual AC vs p-SAC | 27 AC 32 p-SAC | 10 sessions, 1 session per week | Symptom score/quality of life | ↑in both groups no significant group difference | No moxibustion where possibly indicated | |

| Rohrböck et al[23], 2004 | Controlled trial; cross-over Design cross sectional evaluation | Electro-AC vs np-SAC on AC points | 9 IBS 12 healthy controls | 2 treatments (1 AC, 1 PAC) | Perception threshold (barostat) | ↑in both groups no significant group difference | Not randomised; standard AC on BL23 and BL 30; no individual AC pattern; no a priori power calculation | |

| Xiao et al[24], 2004 | Cross over trial; cross-sectional And longitudinal evaluation | TENS vs sham TENS (off- switched) | 24 diarrhea-predominant 20 constipation predominant 30 functional constipation 30 healthy subjects | Cross sectional 2 treatments (1 TENS, 1 sham TENS on 3rd d) longitudinal two months (8sessions) | Perception threshold (barostat) | ↑for TENS in the diarrhea predominant group | TENS with standard pattern on three points (LI4, St36, UB 57) No power calculation selection for long term group unclear (n = 12 of diarrhea predominant) | |

| Fireman et al[25], 2001 | Cross-over design longitudinal evaluation | Acupuncture at LI 4 (AC) vs acupuncture at BL 60 (p-SAC) | 25 | 4 treatments (2 AC, 2 p-SAC,each over a period of 4 wk) | Symptoms | ↑in both groups | Atypical acupuncture(only one point),multiple testing No prior definition of end point No a priori power calculation | |

| Chan et al[26], 1997 | Pilot study; before-after- study | No comparison | 7 | 4 wk | Symptom scores | ↑acupuncture effective(P < 0.01) | No control group standard AC,no individual AC pattern | |

| Kunze et al[27], 1990 | Randomized trial evaluation unclear | Psychotherapy vs AC vs p-SAC vs papaverin vs placebo medication | 60 | Unclear | Subjective symptom scores | Psychotherapy superior to AC and papaverin(P < 0.01) ↑AC superior to p-SAC (P < 0.01) | Patient allocation unclear, partly contradictory type of acupuncture pattern, frequency and performance unclear No power calculation | |

| Functional dyspepsia | Chen et al[28], 1998 | Controlled trial | Standardised AC vs Cisaprid | 18 AC 20 Cisaprid group | 10 sessions (2 d in between) | Symptom score electrogas-trogramm | ↑in both groups no significant group difference | No description of randomization process, allocation concealment,blinding of patients and providers,statistical analysis,drop-outs No sample size calculation No definition of PO No placebo AC control |

| Ulcerative colitis | Joos et al[21], 2006 | RCT | Individual AC vs p-SAC | 15 AC 14 p-SAC | 10 sessions over a period of 5 wk,follow-up 16 wk | PO: Colitis Activity Index (CAI) SO: quality of life, general well-being | ↑AC superior to p-SAC related to PO | Calculated number of patients not reached; Not all outcomes evaluator-blind |

| Yue et al[30] 2005 | RCT | Standardised AC + plum-Blossom needle/cupping vs Sulfasalazine | 43 AC 35 Sulfasalazine group | 10 sessions daily | symptoms | ↑AC superior to Sulfasalazine | No description of randomization process, allocation concealment,blinding of patients and providers,statistical analysis,drop-outs No sample size calculation No definition of PO No placebo AC control | |

| Yang et al[29], 1999 | RCT | Standardised AC vs Salicylazo-sulfapyridinum(5 g/d for the stage of attack 2 g/d for remission) | 32 AC 30 Salicylazo-sulfapyridinum group | 10 sessions (3 d in between),Moxa 3x daily for 10 d | Symptoms examination of feces electrogastrogramm sigmoidoscopic findings | ↑AC superior to Salicylazo- sulfapyridinum for all outcomes | No description of randomization process , allocation concealment,blinding of patients and providers,statistical analysis,drop-outs No sample size calculation, no definition of PO,no placebo AC control p-values unclear in publication, outcome measures unclear | |

| Crohn´s disease | Joos et al[20], 2004 | RCT | Individual AC vs p-SAC | 27 AC 24 p-SAC | 20 sessions over a period of 4 wk,follow-up 12 wk | PO: Crohn's Disease Activity Index (CDAI) SO: quality of life, general well-being | ↑AC superior to p-SAC related to PO No significant group difference for SO ↑in both groups for PO and SO | Not all outcomes evaluator-blind |

| Gastro-paresis (Diabetes) | Wang et al[32], 2004 | RCT | Individual AC vs Domperidone vs no treatment | 35 AC | 2 courses a 10 sessions (5 d between courses) | symptoms | ↑AC superior in comparison to domperidone and no treatment | No description of randomization process , allocation concealment,blinding of patients and providers,statistical analysis, drop-outs No sample size calculation, No definition of PO No placebo AC control |

| Chang et al[31],2001 | Uncontrolled before-after study | Electro-AC on St36 no comparison | 15 | 1 session | Gastral frequency in electrogastro-graphy (ECG) serum parameters:Glucose,Gastrin,Motilin, hpp =human pancr.polypeptide) | ↑for ECG and hPP levels | No control group | |

| Chronic superficial gastritis | Zhao et al[33], 2003 | RCT | Individual AC (8 Methods of Intelligent Turtle) vs individual AC (conventional) | 20 Turtle group; | 1 session | Symptoms | ↑8 turtles superior to AC according syndrome differentiation | No description of randomization process,allocation concealment,blinding of patients and providers,statistical analysis,drop-outs No sample size calculation, No definition of PO No placebo AC Control Assessment of outcome measure unclear |

| Chronic obstipation | Klauser et al[34], 1993 | Uncontrolled before-after-study | Standardised electro-AC | 8 | 6 sessions over a period of 3 wk | Stool frequency colonic transit times subjective feeling | Acupuncture not effective stool frequency and colonic transit time Subjective feeling improved in all patients | No control group |

| Stomach carcinoma pain | Dang et al[35], 1998 | RCT | Individual AC vs acupoint injection therapy vs analgetics | 16 individual AC | 2 mo ( daily sessions for two weeks with 2-3d between two courses) | Analgesic effects leukocyte counts,quality of life,plasma leuk-enkephalines(PLEK) | ↑AC and point injection compared to analgetics for "markedly effective rate" and PLEK ↑for QoL in all groups without group differences | No description of randomization process, allocation concealment, blinding of patients and providers,statistical analysis,drop-outs No sample size calculation, No definition of PO No placebo AC control Assessment of outcome measure unclear |

| Achalasia | Shi et al[36],1994 | Controlled study | Standardised AC vs sedatives | 11 AC; 10 sedatives group | 3 courses à 10 sessions with 3-4 d between courses | Symptoms, x-ray barium meal | ↑AC superior to sedatives for all outcomes | Not randomized No description of statistical analysis and drop-outs No sample size calculation, No definition of PO No placebo AC control |

All trials were reviewed by two separate reviewers (AS; SJ). For each study, the following variables were extracted: study design, acupuncture treatment protocol of active and control group, study duration and number of visits and outcome parameters (Table 1).

Since the review comprised different medical conditions, clinical benefit was not uniformly scored by the various studies. Therefore, all outcomes were extracted and, if adequate information was given, entitled as primary and secondary outcomes.

Furthermore, methodological quality was assessed according to the following quality criteria: existence of a control group, randomization, blinding of patients and evaluators, statistical protocol, description of drop-outs, a-priori sample size calculation, and a-priori definition of primary and secondary outcomes.

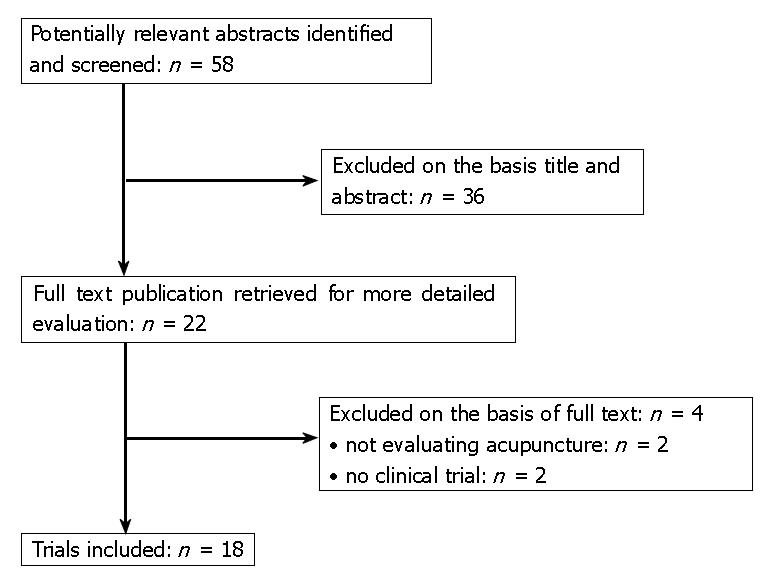

The search identified 58 potentially relevant abstracts. 36 studies were excluded after screening of the title and/or abstract and 4 publications were excluded after obtaining the full text (Figure 1). Characteristics of the remaining 18 publications are summarized in Table 1. Altogether, only 4 studies had a robust randomized controlled design with sufficient information given in the publication to allow firm conclusions from the data[19-22]. All other studies were of poor methodological quality (Table 1).

Seven trials were performed in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS); 1 study was published about functional dyspepsia which has some overlap with IBS. None of the 7 trials was without methodological deficiencies. Only 2 trials were randomized trials[19,22]. Schneider et al[22] evaluated a standardised acupuncture procedure versus the so-called "Streitberger-needle"(np-SAC) administered at non-acupuncture points. A methodological deficiency of this trial is that the calculated number of patients (n = 60) was not reached. However, the authors stated that 566 patients would have been necessary to detect a group difference. Another deficit was that a standardised acupuncture procedure was used in this trial. Forbes et al[19] used an individual treatment procedure for real acupuncture, however, without moxibustion (= heat application of glowing artemisia sinensis) where possibly indicated. To establish a placebo control group, they inserted acupuncture needles into 3 different areas of the body which did not correspond to recognized acupuncture points (p-SAC). In both trials[19,22], a significant improvement in health-related Qol was found in both groups without significant group differences. The remaining 5 IBS-trials had a non-randomised design. Rohrbock et al[23] found that rectal hypersensitivity was reduced by both electro-AC and np-SAC. However, the groups were very small (9 patients with IBS) and there was no information about a-priori power calculation. The study of Xiao et al[24] comprised the highest number of patients (n = 74). Three subgroups of IBS-patients and 30 healthy controls were assessed. Since the authors gave no information about a-priori defined statistical protocol, the increased barostat threshold in the diarrhea predominant group may also be a coincidental finding. The IBS-trials of Fireman, Chan and Kunze had serious methodological deficits preventing suitable conclusions. Fireman et al[25] performed an atypical acupuncture treatment by using only a single acupuncture point. Chan et al[26] had no control group and Kunze et al[27] gave no information about an a-priori defined statistical protocol. The latter found AC superior to SAC by evaluating five subgroups of altogether 60 patients. However, the type of real AC and SAC treatment remained unclear. Chen et al[28] evaluated acupuncture in patients with functional dyspepsia versus drug treatment and found a significant improvement in both groups without any group difference. However, the randomisation, statistical analysis and drop-outs remained unclear (Table 1).

Four trials were performed in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (colitis ulcerosa: n = 3, Crohn's disease: n = 1)[20,21,29,30]. Two trials by Joos et al[20,21] (1 ulcerative colitis, 1 Crohn's disease) had a rigorous methodological design comparing individual acupuncture including moxibustion versus p-SAC. However, in the colitis-study the a-priori calculated number of patients could not be reached[20]. In both trials real acupuncture was significantly superior with regard to disease activity scores (= primary outcomes) but not to QoL questionnaires and symptom scores. However, Qol and symptom scores improved significantly in both groups after treatment compared to baseline. The remaining 2 publications assessed standard acupuncture/moxibustion[29] and standard acupuncture/tapping with plum-blossom needles[30] versus drug treatment (Sulfasalazine) in patients with ulcerative colitis. In both studies, acupuncture was significantly superior to drug treatment regarding symptoms. However, both studies had major methodological deficiencies including insufficient description of endpoints, randomization process and missing power calculations.

Two studies assessed the effect of acupuncture in patients with diabetic gastroparesis[31,32]. In the study of Wang et al[32], individual acupuncture was superior to drug treatment (Domperidone) with a total effective rate of 94% regarding symptoms. However, statistical analyses and calculations for the effective rates were not described in the publication. In the study of Chang et al[31], cutaneous electrogastrography and serum parameters after needling of St 36 were assessed in 15 patients with diabetic gastroparesis. This rather experimental design revealed significant changes in electrogastrography and serum parameters after acupuncture but presented no information about clinical effects.

The four remaining studies evaluated acupuncture in the following medical conditions: chronic gastritis[33], chronic constipation[34], stomach carcinoma pain[35] and achalasia[36]. The study of Klauser et al[34] was an uncontrolled pilot study assessing standard acupuncture in 8 patients with chronic constipation. No changes were found regarding stool frequency and colonic transit times whereas all patients stated a substantive improvement after treatment in this study. In the study of Zhao et al[33], an acupuncture treatment according to ancient theories (8 Methods of Intelligent Turtle) was superior to an individual acupuncture according to syndrome-differentiation. In the study of Dang et al[35] where acupuncture treatment for stomach carcinoma pain was assessed, significantly higher "markedly effective rates" were found for individual AC and acupoint injection compared to analgetics whereas Qol improved in all groups without group differences. In a non-randomized study, Shi et al[36] found therapeutic effects of acupuncture which were significantly superior to a treatment with sedatives for achalasia. However, the latter four studies had severe methodological deficits preventing firm conclusions.

Our systematic review reveals only a few clinical trials, thereof only four robust RCTs, that evaluate the effectiveness of acupuncture treatment in gastrointestinal disorders. The trials of higher methodological quality comprise the medical conditions IBS and IBD. In both conditions, health related QoL improved remarkably after acupuncture, although there was no difference of QoL improvement between real and sham/placebo acupuncture. Altogether, in all trials where QoL or subjective symptoms were assessed, QoL/subjective symptoms improved in AC and SAC groups without significant group differences. In contrast to this, real acupuncture was significantly superior to sham acupuncture with regard to disease activity in the Crohn and Colitis trials. It is not possible to draw sure conclusions from the trials of other gastrointestinal diseases as they are all hampered by major methodological deficits.

The high placebo response of patients with IBS is a widespread phenomenon across different therapy approaches[37] which might be due to enhanced suggestibility[38,39] and other personality factors in these patients. The impact of acupuncture is ideally explained by both trials of Forbes et al[19] and Schneider et al[22] together. Forbes et al could show that real acupuncture with individual pattern is equal to sham acupuncture (with needles at non-acupuncture-points). Thus, an unspecific physiological needling effect could be hypothesized to be responsible for the effectiveness of acupuncture in this trial. However, a physiological unspecific effect seems to be unlikely as placebo acupuncture (with telescopic needles at non-acupuncture points) is equal to a standardised AC in the Schneider study[22]. To summarize for IBS, standardised AC, individual AC, p-SAC and np-SAC provides improvement of QoL. As a consequence, this effect, which is similar to effect sizes achieved with psychotherapeutic interventions[40,41] and antidepressants[40], can be interpreted as psychological effect. This conclusion is supported by Rohrbock et al[23] who demonstrated pain reducing effects of both electro-AC and np-SAC. The psychological effect could be explained by the composition of an explicit 'handling' as a treatment strategy and implicit signalling of a holistic understanding of the patients' problems[22]. In this context, acupuncture could be seen as a complex intervention consisting of several specific and unspecific components[42]. In particular, improvement of QoL might be strongly related to indivisible characteristics and incidental elements, which complicates detection of specific effects[7]. However, at the moment we can not estimate to what extent these potential unspecific effects happen on a psychological level and/or on a physiological level. Further research would be necessary to determine specific effects of acupuncture treatments in IBS although one could raise ethical questions about the necessity of placebo controlled trials to evaluate harmless but effective therapies.

With regard to inflammatory bowel diseases, the study results of Joos et al[20,21] show a statistically and clinically relevant improvement of disease activity pointing to some specific effects of acupuncture. Subgroup analyses in both studies revealed that higher activity grades and disease duration of less than 5 years seem to predict the efficacy of acupuncture therapy. Psychoneuroimmunologic pathways influenced by acupuncture may be an explanation for the presumed acupuncture effects in Crohn and Colitis patients. This needs to be evaluated in further clinical and experimental studies.

In conclusion, efficacy of acupuncture related to QoL in IBS may be explained by unspecific effects. This is the same for QoL in IBD whereas specific acupuncture effects may be found in clinical scores. Further trials would be necessary to evaluate specific and unspecific acupuncture effects in the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders. However, it must be discussed on what terms it would help patients if this harmless and obviously powerful therapy is demystified with further placebo controlled trials. On the one hand this could protect against health fraud, on the other hand the loss of belief in a healing method could destroy its important healing effects.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Kremer M E- Editor Wang HF

| 1. | Kessler RC, Davis RB, Foster DF, Van Rompay MI, Walters EE, Wilkey SA, Kaptchuk TJ, Eisenberg DM. Long-term trends in the use of complementary and alternative medical therapies in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:262-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 496] [Cited by in RCA: 441] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tillisch K. Complementary and alternative medicine for functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gut. 2006;55:593-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ouyang H, Chen JD. Review article: therapeutic roles of acupuncture in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:831-841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Spanier JA, Howden CW, Jones MP. A systematic review of alternative therapies in the irritable bowel syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:265-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Melchart D, Weidenhammer W, Streng A, Reitmayr S, Hoppe A, Ernst E, Linde K. Prospective investigation of adverse effects of acupuncture in 97 733 patients. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:104-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | White A, Hayhoe S, Hart A, Ernst E. Adverse events following acupuncture: prospective survey of 32 000 consultations with doctors and physiotherapists. BMJ. 2001;323:485-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 296] [Cited by in RCA: 272] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Paterson C, Dieppe P. Characteristic and incidental (placebo) effects in complex interventions such as acupuncture. BMJ. 2005;330:1202-1205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 309] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Li Y, Tougas G, Chiverton SG, Hunt RH. The effect of acupuncture on gastrointestinal function and disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:1372-1381. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Li CK, Nauck M, Löser C, Fölsch UR, Creutzfeldt W. Acupuncture to alleviate pain during colonoscopy. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1991;116:367-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cahn AM, Carayon P, Hill C, Flamant R. Acupuncture in gastroscopy. Lancet. 1978;1:182-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Li P, Rowshan K, Crisostomo M, Tjen-A-Looi SC, Longhurst JC. Effect of electroacupuncture on pressor reflex during gastric distension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;283:R1335-R1345. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Jin HO, Zhou L, Lee KY, Chang TM, Chey WY. Inhibition of acid secretion by electrical acupuncture is mediated via beta-endorphin and somatostatin. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:G524-G530. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Kaptchuk TJ. Acupuncture: theory, efficacy, and practice. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:374-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 614] [Cited by in RCA: 575] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cheng XN. Chinese Acupuncture and Moxibustion. Beijing: Foreign Language Press 1987; . |

| 15. | Maciocia G. The foundations of Chinese Medicine. London: Churchill Livingstone 1989; . |

| 16. | Streitberger K, Kleinhenz J. Introducing a placebo needle into acupuncture research. Lancet. 1998;352:364-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 658] [Cited by in RCA: 643] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Park J, White A, Stevinson C, Ernst E, James M. Validating a new non-penetrating sham acupuncture device: two randomised controlled trials. Acupunct Med. 2002;20:168-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | White AR, Filshie J, Cummings TM. Clinical trials of acupuncture: consensus recommendations for optimal treatment, sham controls and blinding. Complement Ther Med. 2001;9:237-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Forbes A, Jackson S, Walter C, Quraishi S, Jacyna M, Pitcher M. Acupuncture for irritable bowel syndrome: a blinded placebo-controlled trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:4040-4044. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Joos S, Brinkhaus B, Maluche C, Maupai N, Kohnen R, Kraehmer N, Hahn EG, Schuppan D. Acupuncture and moxibustion in the treatment of active Crohn's disease: a randomized controlled study. Digestion. 2004;69:131-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Joos S, Wildau N, Kohnen R, Szecsenyi J, Schuppan D, Willich SN, Hahn EG, Brinkhaus B. Acupuncture and moxibustion in the treatment of ulcerative colitis: a randomized controlled study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:1056-1063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Schneider A, Enck P, Streitberger K, Weiland C, Bagheri S, Witte S, Friederich HC, Herzog W, Zipfel S. Acupuncture treatment in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2006;55:649-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rohrböck RB, Hammer J, Vogelsang H, Talley NJ, Hammer HF. Acupuncture has a placebo effect on rectal perception but not on distensibility and spatial summation: a study in health and IBS. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1990-1997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Xiao WB, Liu YL. Rectal hypersensitivity reduced by acupoint TENS in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: a pilot study. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:312-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Fireman Z, Segal A, Kopelman Y, Sternberg A, Carasso R. Acupuncture treatment for irritable bowel syndrome. A double-blind controlled study. Digestion. 2001;64:100-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chan J, Carr I, Mayberry JF. The role of acupuncture in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a pilot study. Hepatogastroenterology. 1997;44:1328-1330. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Kunze M, Seidel HJ, Stübe G. Comparative studies of the effectiveness of brief psychotherapy, acupuncture and papaverin therapy in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Z Gesamte Inn Med. 1990;45:625-627. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Chen R, Kang M. Observation on frequency spectrum of electrogastrogram (EGG) in acupuncture treatment of functional dyspepsia. J Tradit Chin Med. 1998;18:184-187. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Yang C, Yan H. Observation of the efficacy of acupuncture and moxibustion in 62 cases of chronic colitis. J Tradit Chin Med. 1999;19:111-114. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Yue Z, Zhenhui Y. Ulcerative colitis treated by acupuncture at Jiaji points (EX-B2) and tapping with plum-blossom needle at Sanjiaoshu (BL22) and Dachangshu (BL 25)--a report of 43 cases. J Tradit Chin Med. 2005;25:83-84. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Chang CS, Ko CW, Wu CY, Chen GH. Effect of electrical stimulation on acupuncture points in diabetic patients with gastric dysrhythmia: a pilot study. Digestion. 2001;64:184-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wang L. Clinical observation on acupuncture treatment in 35 cases of diabetic gastroparesis. J Tradit Chin Med. 2004;24:163-165. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Zhao C, Xie G, Weng T, Lu X, Lu M. Acupuncture treatment of chronic superficial gastritis by the eight methods of intelligent turtle. J Tradit Chin Med. 2003;23:278-279. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Klauser AG, Rubach A, Bertsche O, Müller-Lissner SA. Body acupuncture: effect on colonic function in chronic constipation. Z Gastroenterol. 1993;31:605-608. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Dang W, Yang J. Clinical study on acupuncture treatment of stomach carcinoma pain. J Tradit Chin Med. 1998;18:31-38. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Shi T, Xu X, Lü X, Xing W. Acupuncture at jianjing for treatment of achalasia of the cardia. J Tradit Chin Med. 1994;14:174-179. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Enck P, Klosterhalfen S, Kruis W. Factors affecting therapeutic placebo respoonse rates in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Nat Clini Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;2:345-355. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Simrén M, Ringström G, Björnsson ES, Abrahamsson H. Treatment with hypnotherapy reduces the sensory and motor component of the gastrocolonic response in irritable bowel syndrome. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:233-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Vase L, Robinson ME, Verne GN, Price DD. The contributions of suggestion, desire, and expectation to placebo effects in irritable bowel syndrome patients. An empirical investigation. Pain. 2003;105:17-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in RCA: 272] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Drossman DA, Toner BB, Whitehead WE, Diamant NE, Dalton CB, Duncan S, Emmott S, Proffitt V, Akman D, Frusciante K. Cognitive-behavioral therapy versus education and desipramine versus placebo for moderate to severe functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:19-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 451] [Cited by in RCA: 411] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | van Dulmen AM, Fennis JF, Bleijenberg G. Cognitive-behavioral group therapy for irritable bowel syndrome: effects and long-term follow-up. Psychosom Med. 1996;58:508-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Joos S, Schneider A, Streitberger K, Szecsenyi J. Acupuncture--needle-pricking within a complex intervention. Forsch Komplementmed. 2006;13:362-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |