Published online May 14, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i18.2523

Revised: April 14, 2007

Accepted: April 30, 2007

Published online: May 14, 2007

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disorder characterized by exacerbations and remissions. The degree of inflammation as assessed by conventional colonoscopy is a reliable parameter of disease activity. However, even when conventional colonoscopy suggests remission and normal mucosal findings, microscopic abnormalities may persist, and relapse may occur later. Patients with long-standing, extensive ulcerative colitis have an increased risk of developing colorectal cancer. Ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer is characterized by an early age at onset, poorly differentiated tumor cells, mucinous carcinoma, and multiple lesions. Early detection of dysplasia and colitic cancer is thus a prerequisite for survival. A relatively new method, magnifying chromoscopy, is thought to be useful for the early detection and diagnosis of dysplasia and colitic cancer, as well as the prediction of relapse.

- Citation: Ando T, Takahashi H, Watanabe O, Maeda O, Ishiguro K, Ishikawa D, Hasegawa M, Ohmiya N, Niwa Y, Goto H. Magnifying chromoscopy, a novel and useful technique for colonoscopy in ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(18): 2523-2528

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i18/2523.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i18.2523

The degree of inflammation in ulcerative colitis (UC) as assessed by conventional colonoscopy is a reliable parameter of disease activity. Even when conventional colonoscopy suggests remission and normal mucosal findings, however, microscopic abnormalities may persist[1,2], and relapse may occur later[3]. UC is a chronic disease with an unknown cause characterized by diffuse mucosal inflammation of the colorectum and a course of exacerbations and remissions[4-8]. The purpose of treatment in patients with UC is thus the achievement of remission and maintenance of quiescence. An important factor in choosing treatment methods is the evaluation of disease activity; this is commonly done using clinical criteria based on symptoms[9] owing to its convenience and noninvasiveness. When clinical criteria are used alone, however, 40% of patients in whom remission is achieved relapse within 1 year[10,11]. This finding indicates the need for colonoscopic and histopathologic assessment also, notwithstanding their disadvantages, including inconvenience, invasiveness and prolongation of the colonoscopic examination.

Patients with long-standing UC are known to have an increased risk for the development of colorectal cancer. Although some investigators recommend prophylactic total proctocolectomy for these high-risk patients, surveillance colonoscopy to detect UC-associated colorectal cancer is generally performed instead. Although UC-associated dysplasia is considered a useful marker of colorectal cancer at surveillance colonoscopy, recognition of dysplasia, particularly flat dysplasia, is hampered by the inflammation-induced granular changes which arise in background mucosa. It is therefore generally recommended that biopsy specimens be taken every 10 cm along the whole colorectum[12]. Even with this coverage, however, a set of 10 biopsy specimens has been theoretically calculated to represent only 0.05% of the total surface area of the whole colorectum[13].

Of interest, recent reports have indicated that careful mucosal examination aided by chromoendoscopy and magnifying endoscopy, and target biopsies of suspicious lesions might provide more effective surveillance than the taking of multiple non-targeted biopsies[14-16].

Severity in ulcerative colitis is generally assessed using symptoms, laboratory data[17], colonoscopic findings[2,18-25] and the histologic degree of inflammation in the biopsy specimens[3,26-29]. Of these, histopathologic assessment is considered the standard for evaluation of disease activity[30]. Observation under conventional colonoscopy is regarded as useful for the evaluation of disease activity, since it offers direct observation of mucosal changes, but it remains controversial whether colonoscopic grade correlates with histopathlogic findings. Notably, the degree of histologic inflammation within biopsy specimens does not necessarily correlate with endoscopic abnormalities[1,2,18,25,31].

Matsumoto et al[14] reported the usefulness of magnifying chromoscopy in the assessment of severity. Magnifying colonoscopy was performed in 41 patients with ulcerative colitis, with findings in the rectum graded according to network pattern (NWP) and cryptal opening (CO). The clinical, endoscopic and histologic grades of activity did not differ between groups categorized by the presence or absence of each finding. However, when the two features were coupled, patients with both visible NWP and CO had a lower clinical activity index and lower grade of histologic inflammation than those in whom neither finding was seen. Further, the presence of breaches in surface epithelium may be an additional factor in future relapse[3], and an altered pattern as defined by magnified colonoscopic views may be predictive of course[14].

Fujiya et al[15] proposed a classification system for magnifying colonoscopic findings in patients with UC which has proved useful for the evaluation of disease activity and prediction of periods of remission. This classification references regularly arranged crypt openings, a villous-like appearance, minute defects of epithelium (MDE), small yellowish spots (SYS), and a coral reef-like appearance. Colonoscopic findings under this classification were compared with histopathologic findings in 61 patients and the usefulness of the classification for predicting relapse was prospectively analyzed in 18. Under conventional colonoscopic examination, all areas evaluated as Matts' grade 1 had a corresponding histopathologic grade of 1. In contrast, most areas assessed as Matts' grade 3 or 4 were diagnosed as histopathologic grade 3 or higher. In contrast, Matts grade 2 mucosa had histopathologic findings that varied from quiescent to active disease. These results suggest that while normal and diseased mucosa are easily recognized by conventional colonoscopy, assessment of the minute mucosal changes that reflect smoldering histopathologic inflammation is much less successful[1,2,18]. Under magnifying colonoscopic examination, in contrast, 37 (82.2%) of the 45 areas in which regularly arranged crypt openings or a villous-like appearance was detected had a corresponding histopathologic grade of 1, while all areas with MDE, SYS, or the coral reef-like appearance had a corresponding histopathologic grade of 2 or higher. In particular, the correlation between histopathologic grade and magnifying colonoscopic findings (r2 = 0.807) was better than that for histopathologic grade versus conventional colonoscopy (r2 = 0.665). This study found that patients in whom MDE was observed during clinical remission frequently experienced relapse within short periods (6 mo) compared with those without this finding, and that 50% of patients who underwent clinical remission still had active inflamed mucosa with MDE[15]. This latter finding correlates with a previous finding that 30% to 60% of patients in remission as determined by clinical symptoms were still in the active stage of ulcerative colitis based on histopathologic findings[18,31].

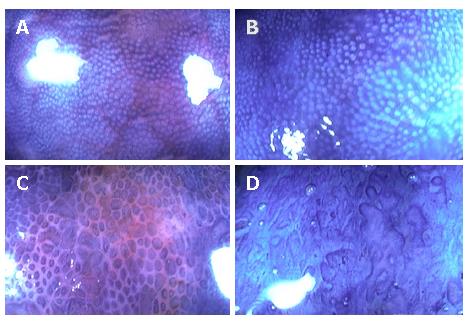

Nishio et al[16] reported that magnifying-colonoscopy (MCS) grade was associated with the degree of histological inflammation and mucosal IL-8 activity in quiescent patients with ulcerative colitis, and might predict the probability of subsequent disease relapse in patients with ulcerative colitis in remission. Magnifying colonoscopy was performed in 113 patients in remission, and the relationship between pit patterns, IL-8 activity, and histological disease activity was evaluated. Pit patterns in the rectal mucosa were classified into four MCS grades on the basis of size, shape, and arrangement (Figure 1). The patients were then followed until relapse or for a maximum of 12 mo. Results showed a positive correlation between MCS grade, histological grade, and mucosal IL-8 activity. Multivariate proportional hazard model analysis showed that MCS grade was a significant predictor of relapse. Moreover, the Kaplan-Meier estimate of relapse during 12 mo follow-up was found to increase with increasing MCS grade, with percentages of 0% for grade 1, 21% for grade 2, 43% for grade 3, and 60% for grade 4. Although MCS grade positively correlated with histological grade and mucosal IL-8 activity, these latter parameters were less accurate predictors of relapse. One reason may be that they are assessed in biopsy specimens derived from a specific and limited area of colorectal mucosa, whereas magnifying colonoscopy allows the observation of a more extended and representative area, and accordingly greater accuracy by MCS grading[16]. These findings demonstrate the usefulness of MCS in the evaluation of disease activity and in predicting relapse in patients with ulcerative colitis.

Colorectal cancer was first recognized as a complication of UC by Crohn and Rosenberg in 1925[32]. UC-associated colorectal cancer differs from sporadic colorectal cancer in a number of ways: it is more common in younger patients[33]; more frequently located in the proximal colon[33]; difficult to detect by barium enema or even by colonoscopy due to its widespread nature[34]; has mucinous and signet-ring histopathological features in approximately half of cases[35]; and is genetically different from the adenoma-carcinoma sequence, with a dysplasia-carcinoma sequence now postulated[36]. Many reports have demonstrated that dysplasia is a useful marker of UC-associated colorectal cancer. The object of surveillance colonoscopy is the detection of dysplasia, particularly a dysplasia-associated lesion or mass (DALM)[37,38]. A classification for UC-associated dysplasia established by the IBD study group in 1983 categorized high-grade dysplasia (HGD), low-grade dysplasia (LGD), indefinite dysplasia (IND) and negative[39]. IND is further classified into three categories: probably negative, unknown and probably positive.

The risk of colorectal cancer is increased in patients with UC, particularly patients who have more extensive colorectal inflammation[31,40], and those with a longer duration of colitis[41-43] have the greater risk. Some reported that patients with an onset of colitis early in life are thought to have a greater risk than older-onset patients[31,42,44]. Further, a recent study by Rutter et al[45] has shown that the severity of colonic inflammation is also highly significant in terms of neoplasia risk.

The purpose of surveillance colonoscopic examinations for patients with UC is the detection of colorectal cancers as early as possible, and prevention of cancer-associated death. One study found that patients with UC-associated colorectal cancer of Dukes' A and B showed good survival, whereas those of Dukes' C showed an extremely poor prognosis[46].

UC-associated colorectal cancer is rarely encountered when disease duration is less than 8-10 years, but risk rises thereafter at approximately 0.5% to 1.0% per year[47]. Most cancers arise in pancolitis, and it is generally agreed that there is little or no increase in risk associated with proctitis and an intermediate risk with left-sided colitis[31,42]. A Swedish group performed a population-based study composed of 3117 patients with ulcerative colitis and concluded that those with total colitis have a far higher risk for the development of colorectal cancer than those with left-sided colitis[31]. In contrast, other reports state that patients with left-sided colitis share the same risk as those with total colitis[48,49] and that disease progression should be taken into consideration[50,51]. Guidelines from the World Health Organization (WHO)[12] and American Gastroenterological Association[52] recommend that patients with pancolitis undergo surveillance colonoscopy at 8 years after onset and those with left-sided colitis at 12-15 years. The recommended interval of surveillance colonoscopy varies by report or guideline as either annual or biannual. Annual colonoscopy will double the cost but may increase sensitivity as compared to biannual colonoscopy. Moreover, an additional consideration is that UC-associated colorectal cancer may advance faster than sporadic colorectal cancer. The answer to this question awaits a cost-benefit analysis[53].

Following initial evidence that dysplasia, a precursor of cancer, may arise in flat mucosa, and presents as a widespread "field effect" distant to cancer sites in 96%-100% of cases[54,55], surveillance protocols recommend the detection of dysplasia by multiple non-targeted random biopsies throughout the colon. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Guidelines advise taking two to four non-targeted biopsies for every 10 cm of colon and rectum[56]. It is still believed that dysplasia is invisible at endoscopy[57], but some reports state that magnifying chromoscopic examination is useful for detecting that occurring in ulcerative colitis[58-60]. Kiesslich et al[61] reported that methylene blue-aided chromoendoscopy in UC surveillance was about three times more useful than conventional colonoscopy for detecting dysplasia, while Rutter et al[58] reported the usefulness of pancolonic indigo carmine dye spraying. The latter investigators compared biopsies of visible abnormalities and non-targeted biopsies taken every 10 cm during a first conventional colonoscopic examination with biopsies of any additional visible abnormalities during a second chromoscopic examination[58]. No dysplasia was detected in 2904 non-targeted biopsies. In comparison, targeted biopsy protocol with pancolonic chromoendoscopy required fewer biopsies (157) yet detected nine dysplastic lesions, seven of which were only visible after indigo carmine application. There was a strong statistical trend towards increased dysplasia detection following dye spraying. Careful mucosal examination aided by pancolonic chromoendoscopy and targeted biopsy of suspicious lesions may therefore represent a more effective surveillance methodology than the taking of multiple non-targeted biopsies[58]. Further, Hurlstone et al[60] observed intraepithelial neoplasia (IN) in flat mucosal change in 37 lesions, of which 31 (84%) were detected using High-Magnification-Chromoscopic-colonoscopy (HMCC), and HMCC significantly increased diagnostic yield for IN compared to conventional colonoscopy (P < 0.01).

MCS and pit pattern diagnosis have been widely used in Japan for non-colitic dysplasia lesions. This method is useful in differentiating invasive carcinoma (Type IIIs, V pit pattern), adenoma (Type IIIL, IV pit pattern), and hyperplastic polyp (Type II pit pattern)[62]. Hata et al examined surgical specimens of UC-associated colorectal cancer by stereomicroscopy, and compared the pit pattern with histopathology. In their study, Type IIIL, IV and V pit patterns corresponded well to dysplastic lesions, while the type I pit pattern corresponded to nondysplastic lesions[59]. Hurlstone et al[60] also emphasized high correspondence between pit pattern using HMCC and histopathology in ulcerative colitis. However, UC-associated colorectal cancer arises in the particular environment of ulcerative colitis, and slight deviations in pit pattern of the mucosa may be difficult to distinguish from epithelial regeneration. Further, UC may also be associated with complex pit patterns of the mucosa that cannot be classified according to the criteria of Kudo[63]. These problems seriously hamper the application of pit pattern diagnosis to UC-associated colorectal cancer surveillance.

On the other hand, some investigators doubt the effectiveness of surveillance colonoscopy in terms of early detection, survival and cost[64,65]. Axon et al[66] reviewed 12 studies of colonoscopic cancer surveillance and criticized its effectiveness. In their review, 92 of 1916 patients were found to have cancer and only 52 (57%) were in Dukes' A or B. Patients with UC-associated colorectal cancer of Dukes' A or B showed a good survival rate, while those of Dukes' C had an extremely poor prognosis[46]. Further, 476 colonoscopies were needed to detect one UC-associated colorectal cancer. The cost-effectiveness of surveillance colonoscopy remains questionable[65-67]. Careful mucosal examination aided by chromoscopy and MCS may be more effective than that by conventional colonoscopy. Although its effectiveness has not been established in terms of cost and survival, surveillance colonoscopy should be performed for patients with long-standing ulcerative colitis until novel methods are established.

While high grade dysplasia is an absolute indication for total proctocolectomy, management of low grade dysplasia is controversial. Some authors believe that LGD is a useful marker in the detection of UC-associated colorectal cancer. Nugent et al[48] reported that 4 of 10 patients with LGD were found to have cancer, and another 2 had HGD in colectomy specimens. Woolrich et al[68] reported that 18% of patients with LGD later developed invasive cancer, and recommended careful follow-up of these patients. Bernstein reported that 29% of LGD patients showed progression at some time to HGD, DALM, or cancer. Further, he reported that patients with LGD had a 19% probability of having cancer at immediate colectomy, and asserted that the finding of definite dysplasia of any grade was an indication for colectomy[64]. Moreover, the St Mark's Hospital surveillance study indicated the 5-year predictive value of LGD for either HGD or cancer was 54% and recommended that patients with persistent LGD should undergo proctocolectomy[69]. In contrast, several authors doubt the usefulness of LGD as a marker for UC-associated colorectal cancer. For example, some LGD lesions have been reported to disappear at close follow-up colonoscopy[34]. Rosenstock et al[13] reported that only 1 of 39 patients with LGD developed invasive carcinoma. Befrits et al[70] reported that colectomy does not appear to be justified in patients in patients with LGD in flat mucosa, even if it is repeated, as no progression to HGD was observed during 10 years of follow-up. Lim et al[71] stated that LGD diagnosis is not sufficiently reliable to justify prophylactic colectomy. Guidelines from the WHO recommend that repeat surveillance colonoscopy be performed at 3-6 mo in those with LGD, and that total proctocolectomy is advisable if dysplasia is multifocal, persistent, or shows DALM[12].

As sporadic adenoma is not infrequent in the general population, incidental cases are also to be expected in patients with UC. Although the detection of sporadic adenoma on colonoscopy is feasible[37,48], a problem is the difficulty in distinguishing this condition from dysplasia in biopsy specimens[39,41]. In fact, several studies have treated both sporadic adenoma and dysplasia as definite dysplasia[70,72]. Suzuki et al[73] recommended taking several biopsy specimens from the surrounding flat mucosa. If specimens are negative for dysplasia, endoscopic polypectomy followed by close surveillance colonoscopy may be adequate. If positive, total proctocolectomy should be considered[73]. Hata et al[59] expected the pit pattern of the surrounding flat mucosa (not the lump itself) to distinguish sporadic adenoma from DALM. In cases of UC-associated dysplasia, the surrounding flat mucosa as well as the DALM itself showed Type IIIL, IV pit pattern, indicating that the dysplasia had spread beyond the lump. With sporadic adenoma, the dysplastic pit pattern (Type IIIL, IV) could be seen only on the surface of the lump, and the surrounding flat mucosa showed a normal pit pattern (type I ), indicating that the dysplastic area was confined and thus that polypectomy was the treatment of choice. Rutter et al[58] reported that small, well-circumscribed lesions detected after dye spraying were endoscopically resectable, and there has been growing evidence that a proportion of such lesions can be safely removed endoscopically without excess cancer risk[74,75].

UC is a chronic inflammatory disease which shows re-peated patterns of activity and remission in most patients. Magnifying colonoscopy is thought to be useful in the evaluation of disease activity and may be useful for predicting relapse in patients with UC. Patients with UC are known to be at increased risk of the development of colorectal cancer. Although its effectiveness has not been established in terms of cost and survival, surveillance colonoscopy should be performed for patients with long-standing UC until more effective methods are established. MCS is thought to be useful for the early detection and diagnosis of dysplasia and colorectal cancer. However, differentiation of dysplasia from epithelial regeneration is difficult both endoscopically and histopathologically. Novel tools are needed to improve the management of UC-associated colorectal cancer.

S- Editor Liu Y E- Editor Wang HF

| 1. | MATTS SG. The value of rectal biopsy in the diagnosis of ulcerative colitis. Q J Med. 1961;30:393-407. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Powell-Tuck J, Day DW, Buckell NA, Wadsworth J, Lennard-Jones JE. Correlations between defined sigmoidoscopic appearances and other measures of disease activity in ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1982;27:533-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Riley SA, Mani V, Goodman MJ, Dutt S, Herd ME. Microscopic activity in ulcerative colitis: what does it mean? Gut. 1991;32:174-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 366] [Cited by in RCA: 396] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ritchie JK, Powell-Tuck J, Lennard-Jones JE. Clinical outcome of the first ten years of ulcerative colitis and proctitis. Lancet. 1978;1:1140-1143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Langholz E, Munkholm P, Davidsen M, Binder V. Course of ulcerative colitis: analysis of changes in disease activity over years. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:3-11. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Edward FC, Truelove SC. The course and prognosis of ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1963;4:299-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 433] [Cited by in RCA: 409] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Selby W. The natural history of ulcerative colitis. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;11:53-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hiwatashi N, Yao T, Watanabe H, Hosoda S, Kobayashi K, Saito T, Terano A, Shimoyama T, Muto T. Long-term follow-up study of ulcerative colitis in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 1995;30 Suppl 8:13-16. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Kornbluth A, Sachar DB. Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults. American College of Gastroenterology, Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:204-211. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Rampton DS, McNeil NI, Sarner M. Analgesic ingestion and other factors preceding relapse in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1983;24:187-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Riley SA, Mani V, Goodman MJ, Lucas S. Why do patients with ulcerative colitis relapse? Gut. 1990;31:179-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Winawer SJ, St John DJ, Bond JH, Rozen P, Burt RW, Waye JD, Kronborg O, O'Brien MJ, Bishop DT, Kurtz RC. Prevention of colorectal cancer: guidelines based on new data. WHO Collaborating Center for the Prevention of Colorectal Cancer. Bull World Health Organ. 1995;73:7-10. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Rosenstock E, Farmer RG, Petras R, Sivak MV, Rankin GB, Sullivan BH. Surveillance for colonic carcinoma in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1985;89:1342-1346. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Matsumoto T, Kuroki F, Mizuno M, Nakamura S, Iida M. Application of magnifying chromoscopy for the assessment of severity in patients with mild to moderate ulcerative colitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46:400-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fujiya M, Saitoh Y, Nomura M, Maemoto A, Fujiya K, Watari J, Ashida T, Ayabe T, Obara T, Kohgo Y. Minute findings by magnifying colonoscopy are useful for the evaluation of ulcerative colitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:535-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Nishio Y, Ando T, Maeda O, Ishiguro K, Watanabe O, Ohmiya N, Niwa Y, Kusugami K, Goto H. Pit patterns in rectal mucosa assessed by magnifying colonoscope are predictive of relapse in patients with quiescent ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2006;55:1768-1773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Descos L, André F, André C, Gillon J, Landais P, Fermanian J. Assessment of appropriate laboratory measurements to reflect the degree of activity of ulcerative colitis. Digestion. 1983;28:148-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Binder V. A comparison between clinical state, macroscopic and microscopic appearances of rectal mucosa, and cytologic picture of mucosal exudate in ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1970;5:627-632. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Alemayehu G, Järnerot G. Colonoscopy during an attack of severe ulcerative colitis is a safe procedure and of great value in clinical decision making. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:187-190. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Carbonnel F, Lavergne A, Lémann M, Bitoun A, Valleur P, Hautefeuille P, Galian A, Modigliani R, Rambaud JC. Colonoscopy of acute colitis. A safe and reliable tool for assessment of severity. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:1550-1557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Blackstone M. Endoscopic interpretation normal and pathologic appearances of the gastrointestinal tract. New York: Raven Press 1984; . |

| 22. | Baron JH, Connell AM, Lennard-Jones JE. Variation between observers in describing mucosal appearances in proctocolitis. Br Med J. 1964;1:89-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 441] [Cited by in RCA: 459] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gomes P, du Boulay C, Smith CL, Holdstock G. Relationship between disease activity indices and colonoscopic findings in patients with colonic inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1986;27:92-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 257] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Holmquist L, Ahrén C, Fällström SP. Clinical disease activity and inflammatory activity in the rectum in relation to mucosal inflammation assessed by colonoscopy. A study of children and adolescents with chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1990;79:527-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Watts JM, Thompson H, Goligher JC. Sigmoidoscopy and cytology in the detection of microscopic disease of the rectal mucosa in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1966;7:288-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Riley SA, Mani V, Goodman MJ, Herd ME, Dutt S, Turnberg LA. Comparison of delayed release 5 aminosalicylic acid (mesalazine) and sulphasalazine in the treatment of mild to moderate ulcerative colitis relapse. Gut. 1988;29:669-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Korelitz BI, Sommers SC. Responses to drug therapy in ulcerative colitis. Evaluation by rectal biopsy and histopathological changes. Am J Gastroenterol. 1975;64:365-370. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Theodossi A, Spiegelhalter DJ, Jass J, Firth J, Dixon M, Leader M, Levison DA, Lindley R, Filipe I, Price A. Observer variation and discriminatory value of biopsy features in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1994;35:961-968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Levine TS, Tzardi M, Mitchell S, Sowter C, Price AB. Diagnostic difficulty arising from rectal recovery in ulcerative colitis. J Clin Pathol. 1996;49:319-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Rao SS, Holdsworth CD, Read NW. Symptoms and stool patterns in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1988;29:342-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ekbom A, Helmick C, Zack M, Adami HO. Ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer. A population-based study. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1228-1233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1294] [Cited by in RCA: 1198] [Article Influence: 34.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Crohn BB, Rosenberg H. Sigmoidoscopic picture of chronic ulcerative colitis (non-specific). Am J Med Sci. 1925;170:220-228. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Bansal P, Sonnenberg A. Risk factors of colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:44-48. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Collins RH, Feldman M, Fordtran JS. Colon cancer, dysplasia, and surveillance in patients with ulcerative colitis. A critical review. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1654-1658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Choi PM, Zelig MP. Similarity of colorectal cancer in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis: implications for carcinogenesis and prevention. Gut. 1994;35:950-954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 289] [Cited by in RCA: 276] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Fogt F, Vortmeyer AO, Goldman H, Giordano TJ, Merino MJ, Zhuang Z. Comparison of genetic alterations in colonic adenoma and ulcerative colitis-associated dysplasia and carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:131-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Blackstone MO, Riddell RH, Rogers BH, Levin B. Dysplasia-associated lesion or mass (DALM) detected by colonoscopy in long-standing ulcerative colitis: an indication for colectomy. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:366-374. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Butt JH, Konishi F, Morson BC, Lennard-Jones JE, Ritchie JK. Macroscopic lesions in dysplasia and carcinoma complicating ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1983;28:18-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Riddell RH, Goldman H, Ransohoff DF, Appelman HD, Fenoglio CM, Haggitt RC, Ahren C, Correa P, Hamilton SR, Morson BC. Dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease: standardized classification with provisional clinical applications. Hum Pathol. 1983;14:931-968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1348] [Cited by in RCA: 1213] [Article Influence: 28.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Greenstein AJ, Sachar DB, Smith H, Pucillo A, Papatestas AE, Kreel I, Geller SA, Janowitz HD, Aufses AH. Cancer in universal and left-sided ulcerative colitis: factors determining risk. Gastroenterology. 1979;77:290-294. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Leidenius M, Kellokumpu I, Husa A, Riihelä M, Sipponen P. Dysplasia and carcinoma in longstanding ulcerative colitis: an endoscopic and histological surveillance programme. Gut. 1991;32:1521-1525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Gyde SN, Prior P, Allan RN, Stevens A, Jewell DP, Truelove SC, Lofberg R, Brostrom O, Hellers G. Colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a cohort study of primary referrals from three centres. Gut. 1988;29:206-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 333] [Cited by in RCA: 324] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Eaden JA, Abrams KR, Mayberry JF. The risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2001;48:526-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1985] [Cited by in RCA: 2079] [Article Influence: 86.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 44. | Devroede GJ, Taylor WF, Sauer WG, Jackman RJ, Stickler GB. Cancer risk and life expectancy of children with ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:17-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Rutter M, Saunders B, Wilkinson K, Rumbles S, Schofield G, Kamm M, Williams C, Price A, Talbot I, Forbes A. Severity of inflammation is a risk factor for colorectal neoplasia in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:451-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 895] [Cited by in RCA: 882] [Article Influence: 42.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Heimann TM, Oh SC, Martinelli G, Szporn A, Luppescu N, Lembo CA, Kurtz RJ, Fasy TM, Greenstein AJ. Colorectal carcinoma associated with ulcerative colitis: a study of prognostic indicators. Am J Surg. 1992;164:13-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Ransohoff DF. Colon cancer in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1988;94:1089-1091. [PubMed] |

| 48. | Nugent FW, Haggitt RC, Gilpin PA. Cancer surveillance in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1241-1248. [PubMed] |

| 49. | Sugita A, Sachar DB, Bodian C, Ribeiro MB, Aufses AH, Greenstein AJ. Colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis. Influence of anatomical extent and age at onset on colitis-cancer interval. Gut. 1991;32:167-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Farmer RG, Easley KA, Rankin GB. Clinical patterns, natural history, and progression of ulcerative colitis. A long-term follow-up of 1116 patients. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1137-1146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 269] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Leijonmarck CE, Löfberg R, Ost A, Hellers G. Long-term results of ileorectal anastomosis in ulcerative colitis in Stockholm County. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33:195-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Winawer SJ, Fletcher RH, Miller L, Godlee F, Stolar MH, Mulrow CD, Woolf SH, Glick SN, Ganiats TG, Bond JH. Colorectal cancer screening: clinical guidelines and rationale. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:594-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1353] [Cited by in RCA: 1246] [Article Influence: 44.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Hata K, Watanabe T, Kazama S, Suzuki K, Shinozaki M, Yokoyama T, Matsuda K, Muto T, Nagawa H. Earlier surveillance colonoscopy programme improves survival in patients with ulcerative colitis associated colorectal cancer: results of a 23-year surveillance programme in the Japanese population. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1232-1236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Morson BC, Pang LS. Rectal biopsy as an aid to cancer control in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1967;8:423-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 453] [Cited by in RCA: 377] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Hultén L, Kewenter J, Ahrén C. Precancer and carcinoma in chronic ulcerative colitis. A histopathological and clinical investigation. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1972;7:663-669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | The role of colonoscopy in the management of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:689-690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Ransohoff DF, Riddell RH, Levin B. Ulcerative colitis and colonic cancer. Problems in assessing the diagnostic usefulness of mucosal dysplasia. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:383-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Rutter MD, Saunders BP, Schofield G, Forbes A, Price AB, Talbot IC. Pancolonic indigo carmine dye spraying for the detection of dysplasia in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2004;53:256-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 392] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Hata K, Watanabe T, Motoi T, Nagawa H. Pitfalls of pit pattern diagnosis in ulcerative colitis-associated dysplasia. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:374-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Hurlstone DP, McAlindon ME, Sanders DS, Koegh R, Lobo AJ, Cross SS. Further validation of high-magnification chromoscopic-colonoscopy for the detection of intraepithelial neoplasia and colon cancer in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:376-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Kiesslich R, Fritsch J, Holtmann M, Koehler HH, Stolte M, Kanzler S, Nafe B, Jung M, Galle PR, Neurath MF. Methylene blue-aided chromoendoscopy for the detection of intraepithelial neoplasia and colon cancer in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:880-888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 616] [Cited by in RCA: 557] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Kudo S, Tamura S, Nakajima T, Yamano H, Kusaka H, Watanabe H. Diagnosis of colorectal tumorous lesions by magnifying endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:8-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 721] [Cited by in RCA: 708] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Sada M, Igarashi M, Yoshizawa S, Kobayashi K, Katsumata T, Saigenji K, Otani Y, Okayasu I, Mitomi H. Dye spraying and magnifying endoscopy for dysplasia and cancer surveillance in ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1816-1823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Bernstein CN, Shanahan F, Weinstein WM. Are we telling patients the truth about surveillance colonoscopy in ulcerative colitis? Lancet. 1994;343:71-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 426] [Cited by in RCA: 362] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Lynch DA, Lobo AJ, Sobala GM, Dixon MF, Axon AT. Failure of colonoscopic surveillance in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1993;34:1075-1080. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Axon AT. Cancer surveillance in ulcerative colitis--a time for reappraisal. Gut. 1994;35:587-589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Jonsson B, Ahsgren L, Andersson LO, Stenling R, Rutegård J. Colorectal cancer surveillance in patients with ulcerative colitis. Br J Surg. 1994;81:689-691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Woolrich AJ, DaSilva MD, Korelitz BI. Surveillance in the routine management of ulcerative colitis: the predictive value of low-grade dysplasia. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:431-438. [PubMed] |

| 69. | Connell WR, Lennard-Jones JE, Williams CB, Talbot IC, Price AB, Wilkinson KH. Factors affecting the outcome of endoscopic surveillance for cancer in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:934-944. [PubMed] |

| 70. | Befrits R, Ljung T, Jaramillo E, Rubio C. Low-grade dysplasia in extensive, long-standing inflammatory bowel disease: a follow-up study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:615-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Lim CH, Dixon MF, Vail A, Forman D, Lynch DA, Axon AT. Ten year follow up of ulcerative colitis patients with and without low grade dysplasia. Gut. 2003;52:1127-1132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Lennard-Jones JE, Melville DM, Morson BC, Ritchie JK, Williams CB. Precancer and cancer in extensive ulcerative colitis: findings among 401 patients over 22 years. Gut. 1990;31:800-806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 327] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Suzuki K, Muto T, Shinozaki M, Yokoyama T, Matsuda K, Masaki T. Differential diagnosis of dysplasia-associated lesion or mass and coincidental adenoma in ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:322-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Rubin PH, Friedman S, Harpaz N, Goldstein E, Weiser J, Schiller J, Waye JD, Present DH. Colonoscopic polypectomy in chronic colitis: conservative management after endoscopic resection of dysplastic polyps. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1295-1300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Engelsgjerd M, Farraye FA, Odze RD. Polypectomy may be adequate treatment for adenoma-like dysplastic lesions in chronic ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1288-194; discussion 1288-1294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |