Published online Mar 28, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i12.1862

Revised: December 23, 2006

Accepted: March 10, 2007

Published online: March 28, 2007

AIM: To study the effect of hepatitis virus infection on cirrhosis and liver function markers in HIV-infected hemophiliacs.

METHODS: We have analyzed the immunological, liver function and cirrhosis markers in a cohort of hemophiliacs co-infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis viruses.

RESULTS: There was no difference in immunological markers among co-infected patients and patients infected with HIV only and those co-infected with one or more hepatitis virus. Although liver function and cirrhosis markers remained within a normal range, there was a worsening trend in all patients co-infected with hepatitis virus C (HCV), which was further exacerbated in the presence of additional infection with hepatitis virus B (HBV).

CONCLUSION: Co-infection with HIV, HBV and HCV leads to worsening of hyaluronic acid and liver function markers. Increases in serum hyaluronic acid may be suggestive of a predisposition to liver diseases.

- Citation: Shen F, Huang Q, Sun HQ, Ghildyal R. Significance of blood analysis in hemophiliacs co-infected with human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis viruses. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(12): 1862-1866

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i12/1862.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i12.1862

Co-infection with hepatitis virus B and C (HBV and HCV) is very common in individuals with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, presumably due to the shared transmission route of these viruses. The prevalence of HCV infection among HIV-infected individuals can be as high as 40% but varies substantially among risk groups[1]; cirrhosis is an increasingly prevalent cause of morbidity in such patients[2]. The prevalence of HCV infection among HIV-infected drug users (IDUs) is 50%-90%[1,3]. HCV co-infection increases the risk of cirrhosis by 10-20 fold in people infected with HIV[4]. This is especially apparent in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), possibly due to the improved survival rate. HAART itself may also influence liver diseases[4]. Co-infection with HBV and HIV is also common, and 70%-90% of HIV-infected individuals had past or active infection with HBV[5]. The prevalence of HIV within a cohort of IDUs in Yunnan, China was found to be 71.9%, 99.3% of them being co-infected with HCV[6]. In another Chinese study, HCV and HIV prevalence was 75% and 18.5% in IDUs, with 58% HCV patients being co-infected with HIV[7]. Treatment with contaminated blood products prior to 1990 resulted in a high prevalence of HIV, HBV and HCV in hemophiliacs; 85% of persons infected with HIV are co-infected with HCV[1,3]. In a multi-center hemophilia cohort study, 30% of HCV seropositive survivors had HIV and 4.6% were HBV carriers[8]. Co-infection data is not available for hemophiliacs in China.

Our data show that in a cohort of HIV-infected hemophiliacs, co-infection with HBV or HCV or both leads to worsening of a key cirrhosis marker, hyaluronic acid (HA). Taken together with recent literature[9], our data suggest that HA levels may be suggestive of progression to liver diseases in these patients.

Laboratory data from the first visit of all hemophiliacs (previously diagnosed with HIV) reported to Shanghai Public Health Center between May and October 2004 were analyzed.

All patients were infected with HIV-1, group M and subgroup B and were on HAART at the time of data collection as per the guidelines issued by China Center for Disease Control (The National AIDS Anti-viral Treatment Guidelines, stavudine (d4T), lamivudine (3TC), and efavirenz). Patients are started on antiretrovirals if their CD4 count is < 200/mm3 or HIV-RNA is > 300000 copies/mL.

All patients co-infected with HCV were on 180 mg PEGylated interferon weekly and ribavirin > 10.6 mg/kg daily. Patients are started on the therapy if their anti-HCV antibody is detected in the serum or HCV-RNA is > 1000 copies/mL, or if they have consistently abnormal aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) values.

Patients with HBV co-infection were all on lamivudine therapy as part of HAART; and at the time of analysis, HBV DNA was below the limit of detection.

Patients infected with HIV only were compared with those co-infected with hepatitis viruses and patients co-infected with either HBV or HCV were compared with patients co-infected with both HBV and HCV.

Data was also collected from a control group of non-haemophiliac patients infected with either HIV or HCV or HBV. These control patients were not on any antiviral therapy at the time of data collection. Data from the control groups were compared with that from co-infected patients.

HIV infection was diagnosed by a screening test on 50 L whole blood (immunogold silver staining kit, Dainablot Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan); confirmatory Western blot was performed at the Center of Disease Control, Shanghai. HBV and HCV infections were diagnosed by real time PCR on 200 L serum (PG Biotec, China, Bio-Rad iCycler). Anti-HBV and anti-HCV antibodies were estimated in 1 mL patient serum by microparticle enzyme immunoassay (ABBOT Diagnostics Division, USA) and ELISA (HENAN Sino-American Bio, China), respectively.

Cell markers were analyzed by FACS on a BD FACSCalibur using 50 μL whole blood and antibodies to CD3/CD8/CD45/CD4 (Becton and Dickinson Co. Ltd).

Cirrhosis markers (HA; cholylglycocholic acid, CG; N-terminal peptide of type III collage, PC3; laminin, LN and collagen IV, IVC) were analyzed by radioimmunoassay (Tongji Unversity Shanghai Radioimmunological Technology Co. LTD). Liver function tests (ALT; AST; alkaline phophatase, ALP; glutamyl transferase, GT; ratio of albumin to globulin, A/G; total bilirubin, TBIL; pro-albumin, PA) were performed using the Roche multi-analyzer.

Unless otherwise stated, values are expressed as mean ± standard error (SEM). Comparisons were done using one-way ANOVA, with statistical software in Microsoft Excel. Statistical significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

The patient data are shown in Table 1. Of the 50 HIV-infected hemophiliacs, 22 (44%) were co-infected with HBV, 39 (78%) with HCV, and 17 (34%) were co-infected with both HBV and HCV. All patients were males, with age ranging from 14 to 68 years (mean = 38.08) at the time of data collection in 2004. No liver function data were available for those with HIV mono-infection (n = 6). Genotype data was available for 31 of the 39 patients co-infected with HCV; 16 were infected with genotype 1b, 10 with 2a and 5 with 2a/2b.

| Hemophiliac patients | ||||

| HIV/HBV | HIV/HCV | HIV/HBV/HCV | HIV | |

| No. | 5 | 17 | 22 | 6 |

| HIV viral load1 | 6.6 × 102 (< 50-105) | 3.12 × 102 (< 50-105) | 2.12 × 102 (< 50-105) | 1.4 × 102 (< 50-104) |

| HBV viral load | Not detectable | Not applicable | Not detectable | Not applicable |

| HCV viral load | Not applicable | 2.51 × 105 (< 103-107) | 8.07 × 104 (103-107) | Not applicable |

| CD42 count | 19.4 ± 3.4 | 21.56 ± 1.9 | 18.05 ± 1.7 | 25.17 ± 1.5 |

| CD4/CD8 | 0.45 ± 0.13 | 0.46 ± 0.06 | 0.41 ± 0.06 | 0.63 ± 0.06 |

| ALT (U/L) | 18.2 ± 2 | 46 ± 8 | 47.6 ± 7.5 | |

| AST (U/L) | 24.2 ± 2 | 44.8 ± 9 | 53.8 ± 9 | |

| TBIL (mol/L) | 7.5 ± 1 | 10.4 ± 2 | 11.3 ± 1 | |

| ALP (U/L) | 188.2 ± 42 | 214 ± 16 | 207.3 ± 15 | |

| γ-GT (U/L) | 39.2 ± 17 | 103.5 ± 23 | 145.7 ± 25 | |

| A/G | 1.41 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.07 | 1.7 ± 0.4 | |

| HA (ng/mL) | 56.8 ± 12 | 73.8 ± 4.5 | 93 ± 15 | |

| CG (μg/dL) | 183 ± 15 | 230 ± 65 | 257 ± 15 | |

| PC3 (μg/L) | 108.3 ± 8 | 106.6 ± 3.2 | 107 ± 2.5 | |

| LN (ng/mL) | 121.2 ± 19 | 111.7 ± 4 | 114 ± 3 | |

| IVC (ng/mL) | 55.5 ± 22 | 46.5 ± 1.5 | 46 ± 1 | |

HIV viral load in patient blood varied from undetectable (< 50 copies) to 1000000 copies/mL and was not different significantly between mono- and co-infected patients, as well as among all three co-infected patient groups. HCV co-infected patients had moderate to high levels of HCV viral load, ranging from below 1000 to 10 million copies/mL (Table 1), there was no significant difference between HIV/HCV and HIV/HBV/HCV infected patients.

Patients infected with HCV and not on antiviral therapy (Table 2) had generally higher viral loads, ranging from more than 2600 to 10 million copies/mL but did not differ significantly from viral loads in co-infected patients.

| Non-hemophiliac patients | |||

| HBV | HCV | HIV | |

| No. | 17 | 14 | 20 |

| HIV viral load1 | Not applicable | Not applicable | 1.4 × 102 (< 50-104) |

| HBV viral load | 8.8 × 106 (2.6 × 103-108) | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| HCV viral load | Not applicable | 9 × 105 (2.6 × 103-107) | Not applicable |

| CD42 | 53.53 ± 4.15 | 41.43 ± 3.04 | 18.25 ± 1.83 |

| CD4/CD8 | 1.93 ± 0.3 | 2.08 ± 0.26 | 0.63 ± 0.06 |

| ALT (U/L) | 266.6 ± 79.4 | 92.64 ± 22.6 | 34.35 ± 11.7 |

| AST (U/L) | 297.5 ± 108 | 77.5 ± 10 | 30.15 ± 3.82 |

| TBIL (mol/L) | 113.4 ± 36 | 31 ± 5.8 | 14.18 ± 1.42 |

| ALP (U/L) | 110 ± 7.9 | 118 ± 19.7 | 45.44 ± 0.63 |

| γ-GT (U/L) | 95.9 ± 17.8 | 87.6 ± 22 | 26.75 ± 5.52 |

| HA (ng/mL) | 323.2 ± 64.6 | 424.14 ± 78 | 83.9 ± 15.25 |

| CG (μg/dL) | 2678 ± 409 | 2050 ± 485 | 410 ± 61 |

| PC3 (μg/L) | 196 ± 21 | 236 ± 36 | 159.6 ± 28.4 |

| LN (ng/mL) | 122.6 ± 7.2 | 118 ± 11 | 106.65 ± 5.24 |

| IVC (ng/mL) | 100 ± 11 | 124 ± 15.6 | 74 ± 11.7 |

All three groups of co-infected patients had low CD4 counts; CD4 cells formed less than 22% of the total T cell population (Table 1). These levels were lower than, but not significantly different from the CD4 counts of HIV mono-infected hemophiliac patients. The mean ratio of CD4 to CD8 cells in peripheral blood was below 0.5 and did not differ between patient groups (Table 1).

Non-hemophiliac patients infected with HBV or HCV had higher CD4 levels, and CD4 cells formed more than 40% of the total T cell population. These levels were higher than those in non-hemophiliac HIV infected patients (18.25%). Similarly, the ratio of CD4 to CD8 cells was higher than 1.9 in HCV and HBV infected non-hemophiliac patients but only 0.63 in HIV infected non-hemophiliacs. When all patients were considered together, the CD4 to CD8 ratio differed significantly between HIV- infected and non-infected patients.

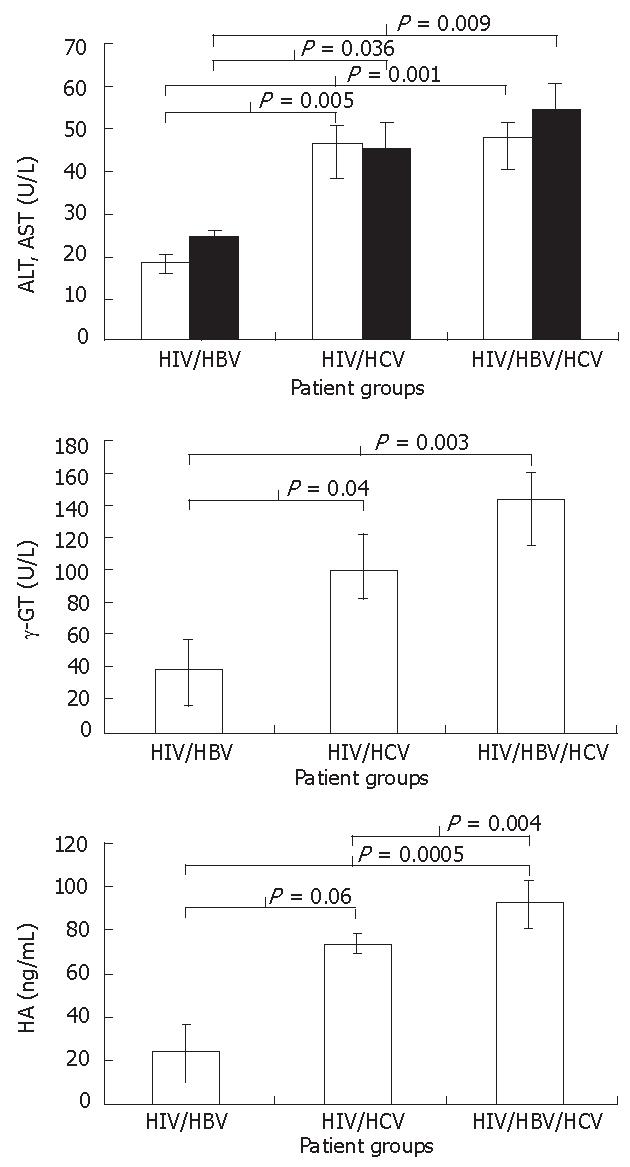

Liver function data in hemophiliacs were available only for co-infected patients. Although all liver function markers analyzed were within normal range, there was a clear trend toward deterioration, i.e., patients co-infected with both HCV and HBV had poorer indicators than those with either HCV or HBV co-infection; liver function markers in patients with HCV co-infection were worse than in those with HBV co-infection. There was a significant difference in ALT between groups with and without HCV co-infection (HIV/HBV vs HIV/HBV/HCV, P = 0.001; HIV/HBV vs HIV/HCV, P = 0.005), but no significant difference between groups with HCV co-infection, although a trend toward further worsening of markers was observed in those with additional HBV co-infection. A similar progressive trend was also found in AST and γGT values (Figures 1A and B). There was no significant difference in ALP, TBIL and A/G among the three groups (Table 1).

Patients infected with HBV or HCV, prior to treatment with antivirals, had overall worsened liver function markers, but similar ALP and γGT levels to co-infected patients during treatment (Tables 1 and 2). All markers were higher in HBV-infected than HCV-infected patients. Liver function markers in non-hemophiliac HIV patients were within normal range and not different from those in hemophiliacs.

Among the five markers of cirrhosis measured and analyzed in this study, four were not different among patient groups (Table 1). Serum HA was lower in patients with HIV/HBV infection than in those with HIV/HCV, with significant difference (P = 0.06), and was significantly lower than in patients with HIV/HBV/HCV infection (P = 0.0005, Figure 1C). Patients with HIV/HCV co-infection had significantly lower serum HA levels than those with HIV/HBV/HCV infection (P = 0.00004). The HA always remained within normal range, suggesting no fibrosis[10] except for one patient with HCV co-infection who had a very high serum HA level. This data were not included in the analysis.

Four of the five cirrhosis markers were considerably elevated in non-hemophiliac patients infected with HBV or HCV, and 2-10 fold that in hemophiliac patients (Tables 1 and 2). Only CG was increased in non-hemophiliac HIV infected patients compared with hemophiliacs.

Our study of a cohort of hemophiliacs infected with HIV show that co-infection with HCV leads to deterioration in liver function and cirrhosis markers, and HA is further worsened in the presence of additional HBV infection. Our data add to the accumulating literature, suggesting that serum HA levels may be used in initial test for progression to cirrhosis.

The prevalence of HCV co-infection within this group was similar to that previously reported in cohorts of IDUs and hemophiliacs[7,8]. Although the prevalence of HBV was lower than HCV (44%), it was higher than the previously reported prevalence of HBs antigenemia within a Chinese population and lower than any other markers of HBV infection[11]. HBV co-infection rates in our study may reflect the endemic nature of the disease rather than transmission via a common route with HIV and HCV. The high incidence (34%) of co-infection with all three viruses argues against this probability.

All patients were treated with lamivudine and HBV viral load was below the detection limit[12]. HCV viral load varied substantially and was below the detection limit in three patients with HCV co-infection only. The three patients also had undetectable HIV viral loads. There was no correlation in viral load or liver function markers between HCV and HIV. In contrast to previous studies[13], HCV infection did not appear to affect CD4 recovery as there was no difference in CD4 levels and CD4/CD8 ratios among the patient groups. Our data could not be used to evaluate the effect of HAART in liver diseases as all co-infected patients were on HAART throughout the study. HCV viral load did not differ significantly between patients on HAART or not, suggesting that HIV infection and HAART in these patients did not have any effect on HCV viral load.

Since the advent of HAART, liver disease has emerged as the major cause of morbidity and mortality in HIV patients co-infected with hepatitis viruses[14]. In our study, there was a trend towards deterioration of liver function associated with infection with HCV. Patients co-infected with HBV had the best results within the group. Patients co-infected with both HBV and HCV had the worst liver function indices, suggesting that HBV and HCV co-infection may have a synergistic effect on disease progression. Both AST and ALT values in HIV/HCV infected patients improved with ribavirin PEG-interferon therapy, reaching levels different from HIV/HBV infected patients after 3-5 mo (data not shown). The same markers in the serum of HIV/HBV/HCV infected patients did not respond to the therapy within a similar time frame.

Antiviral therapy was obviously effective in improving the liver function of HBV and HCV infected individuals as non-treated patients had significantly worse markers of liver disease.

HA levels have shown to correlate with fibrosis and may be used as diagnostic markers[10]. Higher serum HA levels were associated with HCV co-infection, and were further increased in the presence of additional HBV infection. Interestingly, serum HA increased in HIV/HBV/HCV co-infected patients at the time of the data collection from 129.8 ± 12 ng/mL to 210 ± 47 ng/mL, suggesting progression towards fibrosis while no such increase was observed in patients co-infected with HBV or HCV only. As none of the patients progressed to clinically evident cirrhosis during this study (based on normal liver ultrasound results), and liver biopsies were not performed, and we therefore, cannot directly correlate HA levels with cirrhosis. However, our data is in agreement with recent studies showing that some HIV patients co-infected with HCV and having normal liver function, have significant fibrosis as evidenced by liver biopsy[9,15]. Similar to the liver function tests, cirrhosis markers were significantly worse in those infected with either HBV or HCV but not treated with antiviral therapy, showing the efficacy of antiviral therapy in hepatitis patients.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study of the effect of hepatitis virus infection on cirrhosis and liver function markers in HIV-infected hemophiliacs from China, marking an important first step towards a better understanding of hepatitis virus co-infection in HIV patients. The cohort analyzed here represents a special group within China, they have free access to the best medical care through a special initiative of the government and may not reflect the situation in the general population of HIV infected persons.

We wish to thank Dr. John Mills (Department of Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia) and Zhenghong Yuan (Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University, Shanghai, PR China) for critical reading of the manuscript.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Lu W

| 1. | Dieterich DT, Purow JM, Rajapaksa R. Activity of combination therapy with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C patients co-infected with HIV. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19 Suppl 1:87-94. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Martín-Carbonero L, Soriano V, Valencia E, García-Samaniego J, López M, González-Lahoz J. Increasing impact of chronic viral hepatitis on hospital admissions and mortality among HIV-infected patients. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2001;17:1467-1471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zylberberg H, Pol S. Reciprocal interactions between human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus infections. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:1117-1125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Giordano TP, Kramer JR, Souchek J, Richardson P, El-Serag HB. Cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in HIV-infected veterans with and without the hepatitis C virus: a cohort study, 1992-2001. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2349-2354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rodríguez-Méndez ML, González-Quintela A, Aguilera A, Barrio E. Prevalence, patterns, and course of past hepatitis B virus infection in intravenous drug users with HIV-1 infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1316-1322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zhang C, Yang R, Xia X, Qin S, Dai J, Zhang Z, Peng Z, Wei T, Liu H, Pu D. High prevalence of HIV-1 and hepatitis C virus coinfection among injection drug users in the southeastern region of Yunnan, China. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;29:191-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Garten RJ, Zhang J, Lai S, Liu W, Chen J, Yu XF. Coinfection with HIV and hepatitis C virus among injection drug users in southern China. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41 Suppl 1:S18-S24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Goedert JJ, Brown DL, Hoots K, Sherman KE. Human immunodeficiency and hepatitis virus infections and their associated conditions and treatments among people with haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2004;10 Suppl 4:205-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sánchez-Conde M, Berenguer J, Miralles P, Alvarez F, Carlos Lopez J, Cosin J, Pilar C, Ramirez M, Gutierrez I, Alvarez E. Liver biopsy findings for HIV-infected patients with chronic hepatitis C and persistently normal levels of alanine aminotransferase. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:640-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kelleher TB, Mehta SH, Bhaskar R, Sulkowski M, Astemborski J, Thomas DL, Moore RE, Afdhal NH. Prediction of hepatic fibrosis in HIV/HCV co-infected patients using serum fibrosis markers: the SHASTA index. J Hepatol. 2005;43:78-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shimbo S, Zhang ZW, Qu JB, Wang JJ, Zhang CL, Song LH, Watanabe T, Higashikawa K, Ikeda M. Urban-rural comparison of HBV and HCV infection prevalence among adult women in Shandong Province, China. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1997;28:500-506. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Hui AY, Sung JJ. Advances in chronic viral hepatitis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2005;18:400-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Greub G, Ledergerber B, Battegay M, Grob P, Perrin L, Furrer H, Burgisser P, Erb P, Boggian K, Piffaretti JC. Clinical progression, survival, and immune recovery during antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV-1 and hepatitis C virus coinfection: the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Lancet. 2000;356:1800-1805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 646] [Cited by in RCA: 629] [Article Influence: 25.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rosenthal E, Poirée M, Pradier C, Perronne C, Salmon-Ceron D, Geffray L, Myers RP, Morlat P, Pialoux G, Pol S. Mortality due to hepatitis C-related liver disease in HIV-infected patients in France (Mortavic 2001 study). AIDS. 2003;17:1803-1809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Uberti-Foppa C, De Bona A, Galli L, Sitia G, Gallotta G, Sagnelli C, Paties C, Lazzarin A. Liver fibrosis in HIV-positive patients with hepatitis C virus: role of persistently normal alanine aminotransferase levels. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41:63-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |