Published online Dec 7, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i45.7371

Revised: December 28, 2005

Accepted: October 12, 2006

Published online: December 7, 2006

AIM: To investigate the causes of small intestinal bleeding as well as its diagnosis and therapeutic approaches.

METHODS: A retrospective analysis was conducted according to the clinical records of 76 patients with small intestinal bleeding admitted to our hospital in the past 5 years.

RESULTS: In these patients, tumor was the most frequent cause of small intestinal bleeding (37/76), followed by Meckel’s diverticulum (21/76), angiopathy (15/76) and ectopic pancreas (3/76). Of the 76 patients, 21 were diagnosed by digital subtraction angiography, 13 by barium and air double contrast X-ray examination of the small intestine, 11 by 99mTc-sestamibi scintigraphy of the abdominal cavity, 6 by enteroscopy of the small intestine, 21 by laparoscopic laparotomy, and 4 by exploratory laparotomy. Although all the patients received surgical treatment, most of them (68/76) received part enterectomy covering the diseased segment and enteroanastomosis. The follow-up time ranged from 1 year to 5 years. No case had recurrent alimentary tract bleeding or other complications.

CONCLUSION: Tumor is the major cause of small intestinal bleeding followed by Meckel’s diverticulum and angiopathy. The main approaches to definite diagnosis of small intestinal bleeding include digital subtraction angiography, 99mTc-sestamibi scintigraphy of the abdominal cavity, barium and air double contrast X-ray examination of the small intestine, laparoscopic laparotomy or exploratory laparotomy. Part enterectomy covering the diseased segment and enteroanastomosis are the most effective treatment modalities for small intestinal bleeding.

- Citation: Ba MC, Qing SH, Huang XC, Wen Y, Li GX, Yu J. Diagnosis and treatment of small intestinal bleeding: Retrospective analysis of 76 cases. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(45): 7371-7374

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i45/7371.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i45.7371

Due to the lack of specific clinical symptoms and physical signs of small intestinal bleeding and the limitations in the present diagnostic methods for tumors inside the alimentary tract, early diagnosis of small intestinal bleeding is difficult[1-3]. In this article, we retrospectively reviewed and analyzed the diagnostic and therapeutic experiences with 76 cases of small intestinal bleeding patients admitted to our hospital between April 1999 and April 2004.

A total of 76 patients with small intestinal bleeding (44 males and 32 females) were included in the present study. Their age ranged from 15 to 74 years with a mean of 43.5 years. Alimentary tract hematorrhea occurred in all 76 patients. Intermittent dark and bloody stools were found in 57 patients and recurrent dark and bloody stools in 19 with hemorrhagic shocks. Forty patients had accompanying abdominal pain, 4 had accompanying fever and 6 had tangible abdominal lumps.

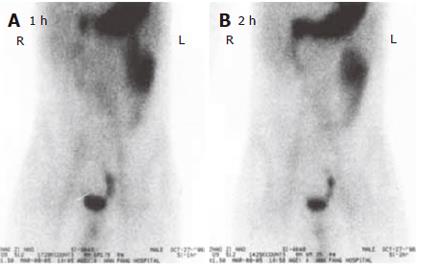

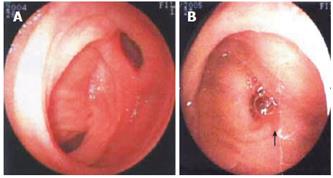

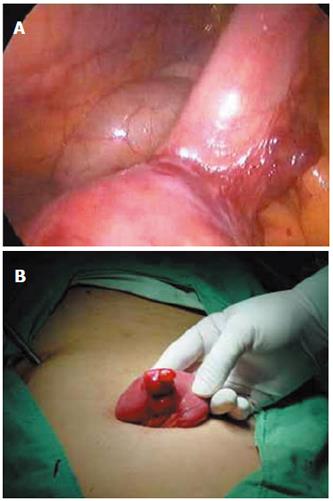

All the 76 patients underwent gastroduodenoscopy, colonscopy, barium meal examination or barium enema to exclude the possible lesions in the stomach, duodenum, colon or rectum. Barium and air double contrast X-ray examinations of small intestine were performed in 43 patients, of them 12 were diagnosed having small intestinal tumors including 1 having Meckel’s diverticulum. 99mTc-sestamibi scintigraphy of the abdominal cavity (ECT) was performed in 36 patients (Figure 1A and 1B). Of them, 16 were definitely diagnosed having small intestinal bleeding including 4 having Meckel’s diverticulum and 2 having small intestinal tumor. Of the 25 patients who received small intestine enteroscopy, 11 had suspected small intestinal bleeding, and 6 had Meckel’s diverticulum (Figure 2A and 2B). Of the 24 patients who received digital subtraction angiography (DSA), 18 were found to have definite small intestinal bleeding, 2 having Meckel’s diverticulum and 6 having small intestinal tumor. Of the 21 patients who received laparoscopic laparotomy, 4 had Meckel’s diverticulum, 4 had definite small intestinal bleeding (Figure 3A and 3B).

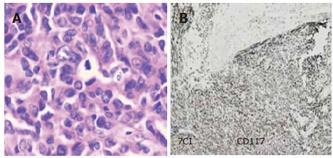

Tumor was the major cause of small intestinal bleeding, which was found in 37 patients. Of these patients 29 were found to have benign stromal tumor, 3 had malignant stromal tumor and 5 had adenocarcinoma (Figure 4A and 4B). Other causes of small intestinal bleeding included Meckel’s diverticulum, angiopathy and ectopic pancreas, which were observed in 21, 15 and 3 patients, respectively. Jejunum bleeding in the small intestine was found in 38 (50%), ileum bleeding in 31 (40%) and multi-foci bleeding in 7 (10%) patients, respectively.

All the patients received surgical treatment, of them 49 received part enterectomy covering the diseased segment and enteroanastomosis, 12 had laparoscopic part enterectomy covering the diseased segment and enteroanastomosis, 9 had laparoscope-assisted part enterectomy covering the diseased segment and enteroanastomosis, 3 had partial excision of ileum and half of the right colon for intestinal cancer, and 3 had conservative excision of intestinal cancer.

One patient with small intestine stromal tumor had recurrent bleeding 10 d after the operation. Stomal ulcer was confirmed by laparotomy and the stoma was then removed. Postoperative death occurred in 3 patients, of them 2 died of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and 1 of severe general infection. The rest 73 patients were cured and discharged from the hospital. Their follow-up time ranged from 1 year to 5 years with a mean of 2.8 years. By the time of this retrospective analysis, all these people were alive except for 2 deaths due to recurrent malignant stromal tumor of the small intestine and 3 deaths due to small intestinal adenocarcinoma. Those who were still alive at the time of this analysis had no alimentary tract bleeding or other complications.

The 3-5 m long small intestine accounts for 75% of the whole gastrointestinal tract. The ansa intestinalis is long-winding and overlapping with active peristalsis and its position in the abdominal cavity varies greatly. Therefore, quick and accurate determination of the cause and foci of small intestinal bleeding is a great challenge for surgeons in clinical practice[1-4]. For unknown causes of alimentary tract bleeding, endoscopy should be first performed to exclude the possible lesions in stomach, duodenum, colon or rectum in order to confirm the bleeding originating from small intestinal segment inferior to duodenum. Subsequently, the bleeding causes can be diagnosed through related examinations.

Small intestine enteroscopy or barium and air double contrast X-ray examination of small intestine can be performed in patients with their bleeding arrested or with little bleeding and stable vital signs to determine the cause of bleeding[2,4]. ECT, DSA, exploratory laparotomy or laparoscopic laparotomy should be performed in patients with unstable vital signs and active bleeding as early as possible to determine the bleeding foci. B-mode ultrasonography or CT scanning should be carried out in patients with abdomen lumps to determine the origin and type of lumps as well as the interrelation with its neighboring organs.

Due to the lack of specific clinical symptoms and physical signs of small intestinal bleeding and the limitations of the present diagnostic approaches to finding lesions inside the alimentary tract, the early diagnosis of small intestinal bleeding is difficult. Barium and air double contrast X-ray examinations of small intestine are the most widely used methods for the diagnosis of small intestinal bleeding. However, since the foci of small intestinal bleeding usually grow outwards, it is difficult to show the tumor, thus resulting in false negatives. Of the 43 patients who received double-contrast radiology of small intestine, 13 were found to be positive for small intestinal bleeding, including 12 cases of small intestinal tumor and 1 case of Meckel’s diverticulum.

Diagnosis of small intestinal bleeding by enteroscopy is time-consuming[5-7]. It is unpleasant for patients and may result in complications of bleeding and perforation or has a high rate of false negative, therefore, its clinical application is confined[8,9]. Recently, a capsule endoscope is under clinic experiment, but this examination cannot perform biopsy and make pathological diagnosis[10-12]. Of the 25 patients who received enteroscopy of small intestine more than once, 11 had suspected small intestinal bleeding and 6 had small intestinal bleeding. The diagnosis rate was less than 8%. Small intestine enteroscopy was performed 5 times in one stromal tumor patient with no positive findings. DSA is the most effective approach to diagnosis of alimentary tract bleeding which shows specific signs of tumor and angiopathy, while embolismic therapy can be performed during DSA diagnosis[3,4]. However, embolismic therapy for small intestinal bleeding has unsatisfying therapeutic efficacy. Even if the embolism is hyper-selective, hematorrhea could reoccur in several hours. Of the 24 patients who underwent DSA, 18 were found to be positive for small intestinal bleeding (including angiopathy in 3, small intestinal stromal tumorin 5, and small intestinal diverticulum in 2 patients). Hematorrhea reoccurred 4-6 h after the embolismic therapy in all the patients.

99mTc-marked erythrocytes for alimentary bleeding imaging are more sensitive to minor intestinal bleeding, and can only determine the position of the bleeding foci[4]. Of the 36 patients who received 99mTc-sestamibi scintigraphy, 16 had positive findings of Meckel’s diverticulum. Abdominal B-mode ultrasonography and CT scanning have limited diagnostic value because stromal tumor, angiocavernoma and Meckel’s diverticulum of small intestine are usually small[13]. Of the patients who received CT scanning, only 4 were found to have abdominal lumps before the operation and none of them could be located. However, CT scaning can display the surrounding tissues of tumor and the involved organs, showing the origin and type of tumor as well as interrelation with its neighboring organs. Based on such findings, distant metastasis can be judged, suggesting that this diagnostic way provides valuable reference for surgical treatment.

Tumor is the major cause of small intestinal bleeding followed by diverticulum and angiopathy of small intestine. Most stromal tumors found in patients with intestinal bleeding caused by tumor are usually benign in nature. Stromal tumors are more common than small intestinal adenocarcinoma, which is not entirely consistent with other studies. Meckel’s diverticulum and angiopathy are the second and third-frequent causes of small intestinal bleeding in such patients. The data reveal that jejunum bleeding often indicates small intestine stromal tumor, while ileum bleeding often originates from Meckel’s diverticulum. There is no definite location of small intestinal angiopathy, but most cases of angiopathy occur in the middle section of small intestine. Angiocavernoma is commonly restricted yet vascular malformation is usually multi-foci, distributing in segments or even spreading along the entire small intestine and its mesentery.

Because of the difficult location and diagnosis of small intestinal bleeding as well as the cautious attitude of surgeons, surgical treatment is only considered for patients with more-than-once negative test results, recurrent hematorrhea and therapeutic failure. Exploratory laparotomy should be performed as early as possible for patients with unknown alimentary tract bleeding causes or for patients who have no specific cause discovered in various clinical examinations. However, patients with hematorrhea in small intestine are generally in poor conditions with unstable vital signs and are usually too vulnerable to receive major operation because they have missed the best time for operation. All the 3 deaths occurred due to the delayed operation. Once the diagnosis is made, different surgical procedures should be adopted according to the nature, location and area of the lesion. Part enterectomy covering the diseased segment and enteroanastomosis should be performed for patients with small intestinal stromal tumor, Meckel’s diverticulum, ectopic pancreas, individual hemangioma and confined vascular malformation. The complete diseased segment of small intestine should be removed in patients with recurrent hemangioma and extensive vascular malformation. But excessive removal of small intestine lesion has to be prevented because short intestinal syndrome may occur.

Laparoscopic laparotomy can clearly and conveniently observe the small intestinal serosa and mesentery. It can assist in the management of discovered lesions. When the focus is discovered by laparoscopy, either laparoscope-assisted enterectomy covering the diseased segment and enteroanastomosis or laparoscopic enterectomy covering the diseased segment and enteroanastomosis can be performed[14-18]. Since December 2002, we have made efforts in applying laparoscope to examine unknown alimentary tract hematorrhea causes that were formerly imperative to laparotomy in 21 patients. The results show that laparoscope-assisted operation has the advantages of quicker location of the focus with noninvasive trauma, less pain and shorter recovery time. Therefore, laparoscope-assisted operation should be set up as the routine method for the treatment of small intestinal hematorrhea[13,15,17,18].

Patients whose bleeding causes could not be specified by laparoscopic laparotomy have only less bleeding from the small intestine that is mostly caused by ectopic pancreas or small intestinal stromal tumor, which is also difficult to locate by exploratory laparotomy. Alternatively, small intestinal enteroscopy during laparoscopy can be carried out by making use of the light-source atop the enteroscope to take fluoroscopy of the suspected area. This in combination with what is seen under the laparoscope usually leads to positive findings. Of the patients who received small intestinal enteroscopy during laparoscopy in this study, 4 had lesions which were cured.

In conclusion, tumor is the major cause of small intestinal bleeding followed by Meckel’s diverticulum, angiopathy, and ectopic pancreas. The main diagnostic approaches are barium and air double contrast X-ray examinations of small intestine, DSA and ECT. Laparoscopic laparotomy or exploratory laparotomy should be performed for patients with long-term alimentary tract bleeding for unknown reasons as soon as possible. Enterectomy covering the diseased segment and enteroanastomosis are the most effective treatment modalities.

S- Editor Wang GP L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Lu W

| 1. | Romãozinho JM, Pontes JM, Lérias C, Ferreira M, Freitas D. Dieulafoy's lesion: management and long-term outcome. Endoscopy. 2004;36:416-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sass DA, Chopra KB, Finkelstein SD, Schauer PR. Jejunal gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a cause of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:214-217. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Bodner J, Chemelli A, Zelger B, Kafka R. Bleeding Meckel's diverticulum. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200:631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rerksuppaphol S, Hutson JM, Oliver MR. Ranitidine-enhanced 99mtechnetium pertechnetate imaging in children improves the sensitivity of identifying heterotopic gastric mucosa in Meckel's diverticulum. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004;20:323-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Keuchel M, Hagenmüller F. Small bowel endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2005;37:122-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Warneke RM, Walser E, Faruqi S, Jafri S, Bhutani MS, Raju GS. Cap-assisted endoclip placement for recurrent ulcer hemorrhage after repeatedly unsuccessful endoscopic treatment and angiographic embolization: case report. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:309-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nguyen NQ, Rayner CK, Schoeman MN. Push enteroscopy alters management in a majority of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:716-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ell C, Remke S, May A, Helou L, Henrich R, Mayer G. The first prospective controlled trial comparing wireless capsule endoscopy with push enteroscopy in chronic gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2002;34:685-689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 435] [Cited by in RCA: 408] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hartmann D, Schmidt H, Bolz G, Schilling D, Kinzel F, Eickhoff A, Huschner W, Möller K, Jakobs R, Reitzig P. A prospective two-center study comparing wireless capsule endoscopy with intraoperative enteroscopy in patients with obscure GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:826-832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jones BH, Fleischer DE, Sharma VK, Heigh RI, Shiff AD, Hernandez JL, Leighton JA. Yield of repeat wireless video capsule endoscopy in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1058-1064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lewis BS, Swain P. Capsule endoscopy in the evaluation of patients with suspected small intestinal bleeding: Results of a pilot study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:349-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 350] [Cited by in RCA: 326] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Martínez-Ares D, González-Conde B, Yáñez J, Estévez E, Arnal F, Lorenzo J, Diz-Lois MT, Vázquez-Iglesias JL. Jejunal leiomyosarcoma, a rare cause of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding diagnosed by wireless capsule endoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:554-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yamaguchi T, Yoshikawa K. Enhanced CT for initial localization of active lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Abdom Imaging. 2003;28:634-636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Loh DL, Munro FD. The role of laparoscopy in the management of lower gastro-intestinal bleeding. Pediatr Surg Int. 2003;19:266-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lee KH, Yeung CK, Tam YH, Ng WT, Yip KF. Laparascopy for definitive diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal bleeding of obscure origin in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:1291-1293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Abbas MA, Al-Kandari M, Dashti FM. Laparoscopic-assisted resection of bleeding jejunal leiomyoma. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:1359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mino A, Ogawa Y, Ishikawa T, Uchima Y, Yamazaki M, Nakamura S, Yukawa T, Matsumoto T, Arakawa T, Hirakawa K. Dieulafoy's vascular malformation of the jejunum: first case report of laparoscopic treatment. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:375-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kok KY, Mathew VV, Yapp SK. Laparoscopic-assisted small bowel resection for a bleeding leiomyoma. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:995-996. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |