Published online Nov 21, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i43.6982

Revised: October 6, 2006

Accepted: October 13, 2006

Published online: November 21, 2006

AIM: To investigate in patients with functional dyspepsia (FD) after an every-day meal whether (1) gastrointestinal (GI) and extra-GI symptoms had any relation with the degree of antral volume, (2) the onset of postprandial symptoms was associated with, and may predict, delayed gastric emptying.

METHODS: In 94 symptomatic FD patients, antral volume variations and gastric emptying were assessed with ultrasonography after a 1050 kcal meal. Symptoms were evaluated with a standardized questionnaire. The association of GI and extra-GI symptoms with antral volumes and gastric emptying were estimated with logistic regression analysis.

RESULTS: Forty percent of patients did not report any symptoms after a meal. Compared to the healthy controls, the antrum was more distended in patients throughout the entire observation period and 37 (39.4%) patients had delayed gastric emptying. Only postprandial drowsiness was associated with antral volume variations (AOR = 1.42; P < 0.001) and with delayed gastric emptying (AOR = 3.59; P < 0.03).

CONCLUSION: In FD patients, GI symptoms are neither associated with antral distension nor with gastric emptying. Drowsiness is associated with antral distension and delayed gastric emptying. The onset of drowsiness is preceded by an increment of antral distension and the duration of the symptom appears to be related to the persistence of antral distension.

- Citation: Pallotta N, Pezzotti P, Corazziari E. Relationship between antral distension and postprandial symptoms in functional dyspepsia. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(43): 6982-6991

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i43/6982.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i43.6982

Patients with functional dyspepsia (FD)[1] complain of several gastrointestinal (GI) and extra-gastrointestinal (extra-GI) symptoms[2-5] that are usually associated with food ingestion[6]. Several pathophysiological abnormalities have been implicated in the etiology of symptoms, but so far they failed to establish a clear-cut association between symptoms and specific function abnormalities and often similar studies provided contrasting findings[6-13]. Despite symptoms are often related to food ingestion, few studies have assessed the relationship between the occurrence of GI symptoms after meal ingestion and gastric functions[6,10,11,14-19] and reported non-univocal results. In addition, investigations performed while patients are symptom-free may miss their underlying pathophysiological mechanisms because as the symptoms, they may wax and wane over time[20]. Ricci et al[14] firstly and others subsequently[15,16,18,21,22] reported a distended fasting antrum and an increased post-prandial antral volume in patients with FD as compared with healthy controls, suggesting that an impaired motor function of the distal stomach is present in a subgroup of patients with FD. However, only two studies[14,15] evaluated the temporal association between the onset of postprandial GI symptoms and antral distension assessed with ultrasonography (US). The first study reported a close association between the onset of the postprandial GI complaints[14] and antral volume increase in the majority (71%) of patients. The second study reported an association between bloating and increased antral area[15]. We have recently shown that a subgroup of patients with FD reported postprandial drowsiness as a bothersome symptom, in addition to the GI dyspeptic ones[5]. Drowsiness is a subjective experience often reported after food ingestion[23]. It has also been shown that solid but not liquid meal results in a decreased sleep onset latency in healthy volunteers[24], suggesting that a post-ingestion mechanism rather than a cephalic stimulus is involved as an initial trigger in mediating the phenomenon.

We aimed to further evaluate the relationship between the onset of postprandial symptoms, both GI and extra-GI symptoms, such as headache and drowsiness, and the modality of the postprandial antral volume increase in FD patients.

The primary aim of the present study was to investigate with regression analysis models, in controlled condition, after an every-day balanced meal, whether upper GI and extra-GI symptoms had any relation with the degree of antral volume assessed with US in FD patients. The secondary aim was to evaluate whether the onset of postprandial symptoms was associated to, and may predict, delayed gastric emptying.

Two hundred and seventeen consecutive patients with chronic symptoms of dyspepsia (143 females, 74 males; age, 42.4 ± 12.2 years;) referred to the gastroenterology outpatient clinic were prospectively assessed. Functional dyspepsia (FD) was defined according to the Rome II criteria[1]. Organic abnormalities, psychiatric illnesses, eating disorders, history of alcohol and caffeine abuse, use of NSAID, steroids or drugs affecting gastric function, previous GI surgery (except appendectomy and cholecystectomy) and systemic disorders were ruled out by history, clinical examination, biochemical investigations, upper GI endoscopy, and transabdominal US. Dyspeptic patients with Rome diagnostic criteria of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and/or referring heartburn and/or regurgitation as predominant or frequent symptoms were excluded from the study.

Severity of epigastric pain and upper abdominal discomfort was graded 0-4 according to its effect on patient’s daily activities: 0 = absent; 1 = mild (present but easily bearable if distracted by usual activities); 2 = moderate (bearable but not influencing usual activities); 3 = relevant (influencing usual activities); and 4 = severe (interruption of usual activities)[5]. Patients were symptomatic at the time of, and in the 3 weeks preceding, the investigation. Dyspeptic symptoms had to be present more than 3 days a week, with pain and discomfort scored at least as moderate (≥ 2).

Overall 123 patients (80 females, 43 males; age, 44 ± 13.5 years) were excluded from the study because of the following diagnosis: 59 with gastroesophageal reflux disease; 15 with IBS; 14 with peptic ulcer disease; 16 with migraine; 3 with psychiatric disorders; 2 with celiac disease; and 14 with not properly reporting symptoms during the test.

Ninety-four consecutive patients (63 females, 31 males; age, 42 ± 12 years) fulfilling Rome II diagnostic criteria of functional dyspepsia[1] and 21 healthy subjects (13 females, 8 males; age, 30 ± 8.5 years) without GI symptoms participated in the study.

Informed consent was obtained from each subject and the Local Ethics Committee approved the study protocol.

An experienced gastroenterologist (EC) interviewed the patients before the study. GI symptoms were enquired by means of the validated Italian version of the Rome II modular questionnaire[25]. The validation process and validity of the translated questionnaire have been formally assessed and approved by the Coordinating Committee of the Rome Foundation (on files of the Committee). The questionnaire also includes items inquiring on demography (5 items), daily habits (10 items), meal timing and composition, alcohol consumption, smoking and sleep patterns, past medical history (3 items), somatic extra-GI symptoms (5 items) as previously reported[2].

Frequency and time relationship with meal ingestion were assessed for each of the following dyspeptic symptoms, as defined by the Rome II criteria[1]: pain or discomfort centered in the upper abdomen, nausea, vomiting, fullness, bloating, early satiety, epigastric burning and belching. Postprandial drowsiness was defined as a state of impaired awareness associated with a desire or inclination to sleep[26]. Furthermore, patients were requested to refer any other symptom they considered to be bothersome and related to meal ingestion.

Gastric antral volume was evaluated at US as previously described[27,28] with 3.5-MHz convex probe (Tosbee, Toshiba, Japan). Gastric emptying was evaluated with US according to previously validated and standardized methods[27-32]. All drugs affecting the GI tract were discontinued at least 3 d before the study. Subjects refrained from smoking 12 h before and during the examination. Beverages, including water, coffee and tea were not allowed before and during the examination. The presence of sleep disturbances the night before the test and the quality of sleep in the last month were specifically enquired. After an overnight fast, subjects ate an ordinary standard solid meal of 1050 kcal containing 140 g bread, 70 g cheese, 80 g ham, (50 % carbohydrates, 25% lipids, 25% proteins) and 250 mL of water. The time of meal ingestion did not exceed 30 min (range, 15-30 min). The same proven-skilled operator (NP) performed gastric antral US measurements, with the subjects standing in the upright position. Subjects were studied in fasting condition, soon after the meal ingestion, at 30 and 60 min after the end of the meal ingestion, and at 60 min intervals thereafter for 300 min. In the intervals between measurements subjects could move freely.

Delayed gastric emptying was defined as the final antral volume exceeding the mean value plus 2SDs of the healthy controls[5].

Patients and healthy controls were requested to report every 30 min any symptom occurring after the meal ingestion. The ultrasonographer was blind for the referred historical symptoms.

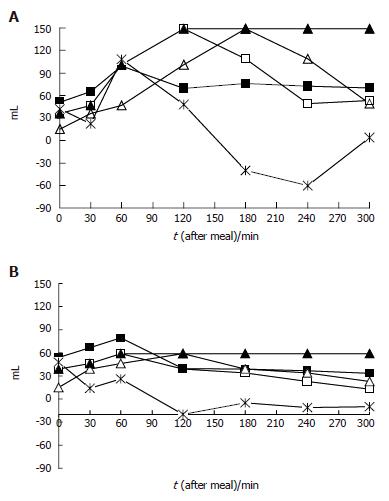

To compare patients and healthy controls as well as temporal meal-related antral volume variations, arithmetic mean, standard deviation, median values and interquartile ranges were calculated. Continuous variables (age, body mass) were compared using student’s t-test. Box-plots[33] were used to provide an immediate graphical evaluation of the postprandial gastric antral volume distribution during the study period. Linear regression analysis for repeated measurements was applied to evaluate during the study period whether there were differences in the antral volumes between patients and healthy controls. The cumulative probability of developing symptoms during the 5 h study period was evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Logistic regression models[34] were applied to estimate crude (OR) and adjusted odds ratios (AOR) for age, body mass index (BMI) and gender, and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) of having an association between antral volume variations and presence/absence of each GI and extra-GI symptom at each time interval evaluated. We also investigated specific transformations of the current gastric antral volume evaluated for a 10 mL unit change as follows (Figure 1 A and B): (1) the antral volume value at the preceding time interval; (2) the antral volume delta variation between two consecutive measurements; (3) the mean weighted antral volume value at each measurement (i.e., at each time when the volume was measured, the value obtained as the arithmetic mean of the current value together with all previous measurements); (4) the maximal antral volume value reached after a meal between the current and the previous measurement.

Logistic regression analysis was also applied to estimate crude and adjusted odds ratios of having delayed gastric emptying for each symptom, fasting antral volume, gender, age, and BMI. We reported results from multiple logistic regression analyses, obtained through a backward selection strategy having excluded factors with a P value >0.20 obtained by a likelihood-ratio test[33]. Two-sided P values were defined statistically significant when P < 0.05, and marginally significant when 0.05 < P < 0.2. All the analyses were performed using STATA release 8.0[35].

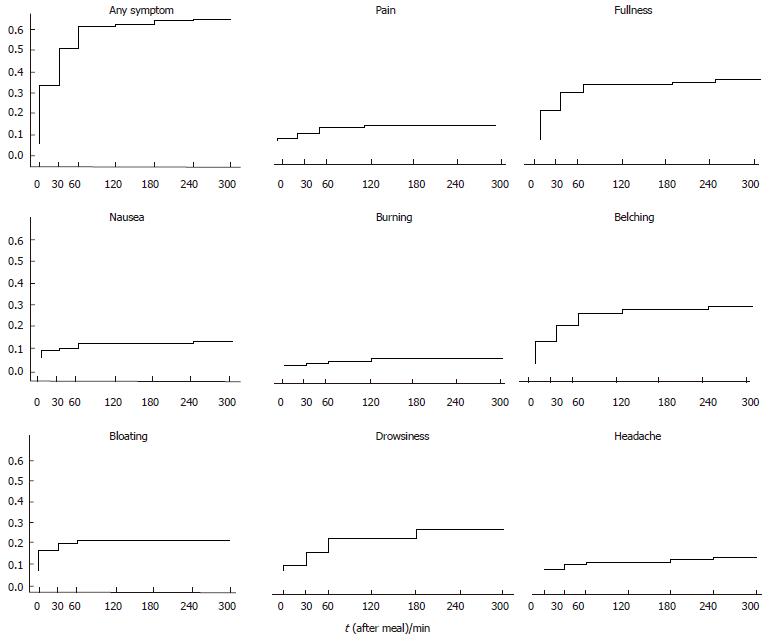

At inclusion, all FD patients reported frequent pain or discomfort (60% of them almost daily) graded at least as moderate. Demographic characteristics of the subjects evaluated are summarized in Table 1. There was no significant difference between the healthy controls and the FD patients for BMI and gender, whereas the controls were younger (P < 0.001) than the FD patients. After a meal, none of the healthy subjects reported any symptoms. Of the FD patients, 39 (41.5%) did not refer any symptoms and 55 (58.5%) reported one or more GI and extra-GI symptoms. In this group of 55 symptomatic patients, postprandial drowsiness was reported as a predominantly bothersome symptom in 17 patients, presenting as the only symptom in 3, in association with pain in 3, with fullness in 6, with pain and fullness in 2, with belching in 2 and with bloating in 1. Reported symptoms’ severity in the medical history did not significantly differ between the patients with and without postprandial symptoms during the investigation. The cumulative probability to develop at least one of the GI and extra-GI symptoms was 58.5% (Figure 2). None of the patients referred early satiety, vomiting and heartburn (not shown in Figure 2). Despite the patients with history of regurgitation were excluded from the study, 2 patients referred postprandial acid regurgitation (not shown in Figure 2 and Tables 2 and 3). The percentage of patients with symptoms at each evaluated time interval is reported in Table 2. Among the patients who referred at least one symptom, 55.5% had the first symptom within 60 min after meal ingestion. Postprandial drowsiness started later (71.5 ± 64.8 min) than dyspeptic symptoms (38.3 ± 55.4 min, P < 0.001).

| Healthy controls | FD patients | P | |

| (n = 21) | (n = 94) | ||

| Age median (IQR) yr | 27 (26-29) | 42 (31-52) | < 0.001 |

| BMI median (IQR) kg/m2 | 22.4 (20-23) | 22.0 (19.8-25.0) | 0.47 |

| Female (%) | 13 (61.9%) | 62 (66.0%) | 0.72 |

| Time (min) | Pain (%) | Fullness (%) | Bloating (%) | Nausea (%) | Belching (%) | Burning (%) | Headache (%) | Drowsiness (%) | Any (%) |

| 0 | 1 | 13.8 | 9.6 | 3.2 | 10.6 | 0 | 0 | 2.1 | 26.6 |

| 30 | 3.2 | 22.3 | 12.8 | 4.3 | 18 | 1 | 2.1 | 7.5 | 44.7 |

| 60 | 6.4 | 24.5 | 14.9 | 5.3 | 22.3 | 2.1 | 3.2 | 13.8 | 54.3 |

| 120 | 6.4 | 24.5 | 14.9 | 5.3 | 24.5 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 13.8 | 54.3 |

| 180 | 4.3 | 20.2 | 12.8 | 5.3 | 20.2 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 17 | 48.9 |

| 240 | 3.2 | 14.9 | 10.6 | 5.3 | 18 | 3.2 | 4.3 | 15.9 | 43.6 |

| 300 | 2 | 12.8 | 9.6 | 5.3 | 15.9 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 12.8 | 38.3 |

| At least once | 7.4 | 28.7 | 14.9 | 7.4 | 26.6 | 3.2 | 5.3 | 18 | 58.5 |

| Current AV | Previous AV | Delta AV | Mean weighted AV | Maximal AV | |||||||||||

| (per 10 mL unit increase) | (per 10 mL unit increase) | (per 10 mL unit increase) | (per 10 mL unit increase) | (per 10 mL unit increase) | |||||||||||

| Symptom | AOR | 95% CI | P | AOR | 95% CI | P | AOR | 95% CI | P | AOR | 95% CI | P | AOR | 95%CI | P |

| Pain | 0.96 | 0.79-1.18 | 0.72 | 0.96 | 0.78-1.17 | 0.67 | 1.03 | 0.93-1.14 | 0.54 | 0.94 | 0.67-1.31 | 0.72 | 0.9 | 0.69-1.19 | 0.49 |

| Fullness | 0.99 | 0.84-1.17 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.82-1.18 | 0.88 | 1 | 0.95-1.06 | 0.82 | 0.95 | 0.73-1.25 | 0.74 | 0.97 | 0.83-1.13 | 0.68 |

| Bloating | 1.21 | 0.98-1.49 | 0.07 | 1.22 | 0.98-1.51 | 0.06 | 0.99 | 0.93-1.05 | 0.7 | 1.37 | 0.99-1.89 | 0.05 | 1.21 | 0.99-1.48 | 0.06 |

| Nausea | 0.99 | 0.76-1.3 | 0.98 | 1.06 | 0.8-1.4 | 0.67 | 0.84 | 0.7-1 | 0.05 | 1.18 | 0.82-1.69 | 0.37 | 1.17 | 0.94-1.44 | 0.15 |

| Burning | 0.87 | 0.55-1.38 | 0.57 | 0.81 | 0.39-1.67 | 0.58 | 1.1 | 0.87-1.39 | 0.39 | 0.68 | 0.2-2.25 | 0.53 | 0.64 | 0.17-2.33 | 0.5 |

| Belching | 1 | 0.84-1.19 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.78-1.17 | 0.67 | 1.07 | 1.01-1.12 | 0.008 | 0.94 | 0.69-1.27 | 0.69 | 0.98 | 0.82-1.17 | 0.81 |

| Headache | 1.04 | 0.77-1.4 | 0.79 | 1 | 0.77-1.31 | 0.96 | 1.03 | 0.88-1.2 | 0.69 | 0.9 | 0.58-1.43 | 0.68 | 0.93 | 0.7-1.23 | 0.64 |

| Drowsiness | 1.42 | 1.16-1.73 | 0.001 | 1.33 | 1.08-1.65 | 0.007 | 1.12 | 1.06-1.19 | 0.001 | 1.46 | 1.05-2.01 | 0.02 | 1.26 | 1.03-1.53 | 0.02 |

| Palpitation | 1 | 0.72-1.4 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.71-1.38 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.9-1.06 | 0.67 | 0.89 | 0.49-1.62 | 0.7 | 0.93 | 0.65-1.32 | 0.68 |

| Any symptom | 1.13 | 0.97-1.31 | 0.12 | 1.1 | 0.94-1.3 | 0.24 | 1.03 | 0.99-1.08 | 0.11 | 1.15 | 0.9-1.46 | 0.25 | 1.11 | 0.95-1.29 | 0.18 |

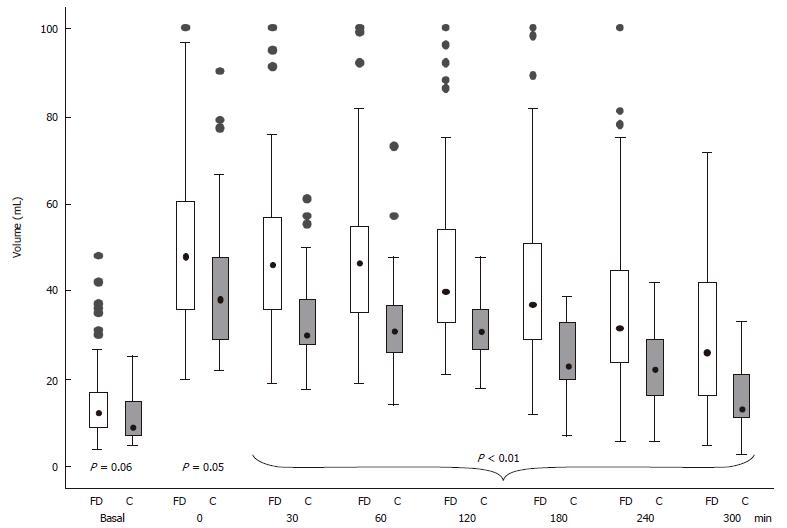

Antral volume before, immediately (time 0) and during the 300 min observation period after meal ingestion in the controls and the FD patients is shown in Figure 3. In the FD patients, the postprandial antral volume was significantly larger compared to the controls (P < 0.05) from the end of meal ingestion up to the final observation. The multiple linear regression model showed that in the postprandial period antral volume, adjusted for gender and age, was higher in the dyspeptic patients compared to the controls with a difference in volume value of 11 mL during the entire period (P < 0.01). Gastric emptying was delayed in 37 (39.4%) of the FD patients.

Odds ratios simultaneously adjusted for minutes after meal, BMI, age and gender in predicting the occurrence of GI and extra-GI symptoms evaluated for each of the antral volume transformations described in Figure 1 are reported in Table 3. The occurrence of postprandial drowsiness was related to (1) the current antral volume value, (2) the antral volume value at the previous time interval, (3) the antral volume delta variation between two consecutive measurements, (4) the mean postprandial weighted antral volume and (5) the maximal antral volume value reached after a meal. The occurrence of nausea and belching was related to the antral volume delta variation between two consecutive measurements. The occurrence of bloating was significantly related to a mean postprandial weighted antral volume, and marginally associated with (1) the current antral volume value, (2) the antral volume value at the previous time interval, and (3) the maximal antral volume value reached after a meal.

Age was the only factor associated with the occurrence of some of the GI and extra-GI meal-related symptoms. Particularly, the occurrence of postprandial drowsiness was significantly associated with older age (AOR = 1.05 per 1 year increase, P < 0.02), while pain was marginally related to younger age (AOR = 0.96, P < 0.04). Epigastric burning was marginally related to older age (AOR = 1.11, P < 0.03).

The estimated AORs of having delayed gastric emptying are shown in Table 4. After a backward selection, only fasting antral volume and postprandial drowsiness were significantly associated with delayed gastric emptying, while no statistically significant relationship was found with age, gender and BMI. Fasting antral volume was significantly associated with delayed gastric emptying, increasing the OR of 93% for any additional volume increase of 5 mL.

An unexpected finding of this study was that more than 40% of symptomatic patients at the time of, and in the 3 wk preceding, the investigation did not refer any symptoms when challenged with a normal meal in controlled condition. The lack of any difference in the demography and symptom presentation between symptomatic and symptom-free patients during the investigation excludes a patient selection bias and indicates that the well known long-term variability[20] of dyspeptic symptoms may occur even over a short period of time.

Ultrasonography is a reliable method to estimate in normal physiological conditions gastric antral volume during fasting and after a meal[27-32]. The serial US measurements of the antral volume enable to assess directly the time curve of antral distension, and indirectly the gastric emptying time. Ricci et al[14] first reported a close association between the onset of the usual postprandial complaints and an antral volume increase in the majority of FD patients. Hausken et al[15] found an association between a wide antral area and bloating. Both studies, however, did not comparatively investigate the antral volume of the FD patients who remained symptom-free after meal ingestion.

Several other studies reporting non-univocal results have attempted to correlate the occurrence of symptoms in FD patients with proximal and distal stomach distension[10,11,17,36,37], gastric volumes[16,19,38-40] or gastric food retention[6,21,22]. These studies were performed at the end[16], 30 min[19] and 1 h[11] after meal ingestion, with either invasive techniques or not physiological ingestion of meals that caused dyspeptic symptoms also in healthy controls[16,17,19,39,40].

This study assessed, in physiological conditions after a normal meal, the relationship between gastric emptying, antral volume variation and postprandial symptoms in symptomatic compared to asymptomatic dyspeptic patients and healthy subjects. The meal was a normal every day meal. Differing from previous findings at multivariate analysis, gender did not have any relationship with postprandial antral distention or with the modality of gastric emptying[22]. The different results of this study may be explained by the larger number of patients studied.

The antral volume reached its maximal value soon after the end of meal ingestion and subsequently decreased throughout the observation period in both controls and FD patients (Figure 3). However, independently from the concomitant presence of GI dyspeptic symptoms, FD patients showed an antral volume greater than healthy controls, confirming the presence of an altered intragastric meal distribution in FD patients[14-16,21,22]. It has been suggested that impaired accommodation of the proximal stomach to a meal underlies the increased distribution of gastric contents in the distal stomach[21,38].

The antral volume variations and gastric emptying were evaluated for a long postprandial period, i.e. 5 h, thus enabling to detect a subgroup of patients in whom the over distension of the antrum occurred later than, and independently from, an early postprandial altered motor function of the proximal stomach.

The most relevant finding of this study was that postprandial drowsiness was the only of the GI and extra-GI symptoms to be highly significantly associated with antral volume and its transformations.

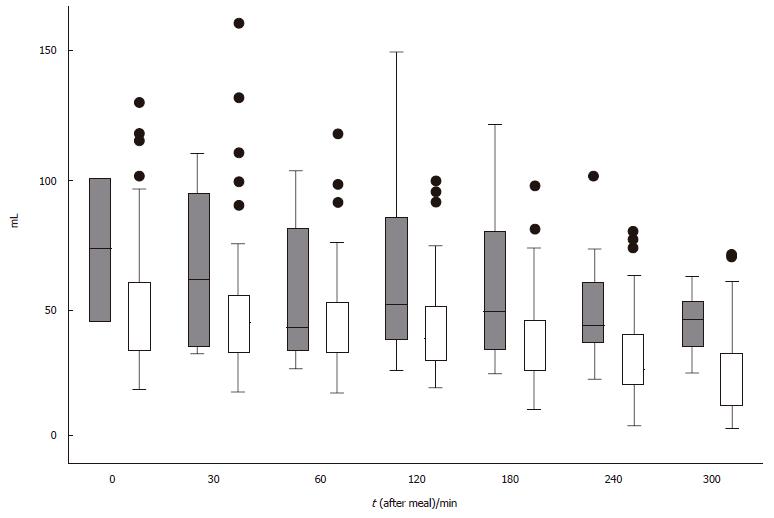

In patients with postprandial drowsiness, antral volume reached the maximal value 2 h after the meal and did not show a progressive decrement throughout the observation period (Figure 4). The occurrence of postprandial drowsiness was significantly associated with the current and mean weighted antral volume, supporting the time-relationship with antral distension. However, the association with delta antral volume change suggests that its onset is associated with the degree of time-related antral distension rather than the antral volume per se. Finally, the finding of an association between drowsiness and the antral volume assessed at the preceding observation period suggests that the antral distension precedes the onset of drowsiness. It could be argued that the fasting and the immediate postprandial antral volumes included in the analysis might have inappropriately contributed to the subsequent antral volume transformation, therefore affecting the results of the present study, but their exclusion from the analyses did not change the results. Furthermore, it has been shown that subtracting the fasting from the final postprandial antral volume, the latter is still greater in dyspeptic patients than in controls, thereby indicating a genuine greater postprandial antral distension in patients compared to healthy controls[5].

At present, whether increased antral volumes may reflect hypotonia of the antral muscular wall or intraluminal distension secondary to gastric retention or to an overload caused by an impaired accommodation of the proximal stomach[21,38], or an increased duodenogastric reflux could not be addressed in the present study.

Several studies indicate that a variable degree of sleepiness after a meal is a common sensation[23,24,41-43] in healthy subjects and may also influence food intake[44]. Studies assessing daytime sleepiness with standard tests, in healthy subjects showed that (1) sleep onset latency was significantly shorter after a caloric meal than after water[24] and sham feeding[45], and (2) the occurrence of postprandial sleepiness was neither related to the fat composition of the test meal nor to the circadian variation in sleepiness[23]. Finally, in healthy subjects, it has been shown that in comparison with an equal volume of water and equicaloric liquid meal, a solid meal results in decreased sleep onset latencies[24]. These results, taken together with the observation that drowsiness may occur after intravenous administration[46] of cholecystokinin (CCK), support the hypothesis of a peripherally circulating hormone of GI origin that mediates postprandial sleepiness. It is conceivable that meal ingestion may release CCK and other neuroendocrine substances, such as 5-HT3, that affect the state of consciousness directly or activating vagal nerve afferences or releasing other sleep-promoting substances, such as insulin[47,48]. Several animal studies indicate that CCK sleep-promoting and food intake-reducing effects are closely associated, presumably expressing different, yet related, manifestations of satiety[47].

Postprandial drowsiness reported in this study refers to a sensation regarded to be bothersome enough to interfere with the daily activities. However, the sensation of drowsiness may vary from slight to severe and may be related to sleep disturbances. Sleep disturbances were enquired specifically and patients reporting postprandial drowsiness did not report any sleep disturbances. In the present study, older age in FD patients was an independent factor adjusted for antral volume variables for the occurrence of drowsiness. Control subjects and dyspeptic patients were not balanced for age, however, in the age-adjusted model, the presence of drowsiness in FD patients was associated only with antral volume variations. In addition, it has been shown that in healthy subjects, postprandial drowsiness is related to a younger age and to a greater food intake compared to older subjects[44]. In the present study, healthy controls, although significantly younger than FD patients, did not report any symptom. It would therefore appear that, in contrast with healthy controls, drowsiness reported by older dyspeptic patients was neither related to sleepiness nor to physiological change of postprandial sleep latency. However, we neither evaluated with objective measures postprandial sleep latency or the severity of postprandial drowsiness nor we specifically evaluated physiological adaptive variation or an altered state of the autonomic nervous system that could justify the occurrence of postprandial drowsiness in our patients[41].

Of the GI symptoms conventionally considered to be a manifestation of dyspepsia, only bloating showed a statistically significant association with the postprandial weighted antral volume and, to a lesser degree, with all the other antral volume variables, confirming previous observations[15,16,37]. Bloating has been frequently reported in healthy subjects in barostat studies, in caloric and even in water drink tests, without any relationship with altered gastric motor function[11,17,44]. In our study, nausea and belching were associated only with antral volume delta change, whereas all the other GI dyspeptic symptoms were not related to any of the assessed antral volume variables. Postprandial fullness is a common sensation even in healthy subjects and it has been reported to be associated with an increase of the antral area[49,50]. In the present study, none of the healthy subjects and about 50% of the study patient population referred fullness that was not associated with any of the antral volume variables evaluated. The frequent occurrence of bloating and postprandial fullness in healthy subjects together with the absence of a constant and univocal association with gastric functions limits the interpretation of the pathophysiological mechanisms of these symptoms in FD patients. Nausea is a non-specific GI symptom that could be elicited by the direct instillation of acid in the duodenum[51], i.e. a condition likely mimicking a physiological condition. Several studies highlighted the potential key role of the duodenum in the symptom generation in functional dyspepsia[51-53]. Hypersensitivity of the duodenum to acid infusion as well as duodenal distension have been reported to elicit upper GI symptoms[51-53]. However, the present study does not allow one to draw any conclusion about the role of the duodenum in the occurrence of symptoms and further investigations are needed.

Early satiety, which is one of the cardinal dyspeptic symptoms and was referred in the medical history by 45% of our patients population, did not occur after a meal in controlled condition in any of the investigated patients. It is conceivable that the sensation referred by the patients was more likely fullness or bloating that had induced the patients to terminate prematurely food ingestion to prevent further discomfort. It has been indeed shown that perception of fullness is a useful predictor of food intake[44,50]. If so, the definition of early satiety as an unpleasant sensation that forces one to stop eating, and the numerous studies in which this symptom has been related to specific function disorder of the stomach, should be reevaluated.

Nevertheless, a relevant limitation of this study is that except for pain and discomfort, severity of postprandial symptoms was not assessed, thus precluding any evaluation of its possible relationship with antral distension.

A significant proportion of FD patients complain of psychological symptoms and the presence of anxiety has been demonstrated in about 70% of these patients[22]. We excluded the patients with eating disorders and clinically evident psychological disorders like major depression from our study; however, we did not fully evaluate the psychological status of the patients.

Despite that it has been widely debated whether a delayed gastric emptying is a relevant factor in causing dyspeptic symptoms, to our knowledge, none of the previous studies evaluated concurrently and in physiological conditions the modality of the gastric emptying and the occurrence of symptoms in FD patients after an ordinary every day meal. In the present study, 39% of FD patients had delayed gastric emptying, but it did not have any relationship with the occurrence of dyspeptic symptoms during the test. A previous study reported a delayed gastric emptying in 41% of the patients and a rapid initial gastric emptying in 43% of them that were associated with higher symptoms score after a challenge meal[19]. Thus, it would appear that a delayed gastric emptying per se does not play any role in the origin of the usual dyspeptic symptoms.

The present study confirms our previous finding[5] that patients referring postprandial drowsiness have a greater probability to have delayed gastric emptying than controls and dyspeptic patients without post-prandial drowsiness. Differently from the usual dyspeptic symptoms, drowsiness is a late postprandial complaint occurring significantly later than GI symptoms and is related with antral distension and delayed gastric emptying. It would therefore appear that the two conditions are associated with the onset, and the persistence of postprandial drowsiness in this subgroup of FD patients. We cannot draw any definitive conclusion about the separate role, if any, played by delayed gastric emptying and antral distension, either alone or in combination, in the occurrence of postprandial drowsiness in FD patients.

In conclusion, our study assessed in controlled conditions the relationship between gastrointestinal and extra-gastrointestinal symptoms arising after a normal balanced meal, and antral distension and gastric emptying. Postprandial gastrointestinal symptoms do not have any constant or predictable relationship with antral distension and gastric emptying in functional dyspepsia patients. Of the extra-gastrointestinal symptoms, postprandial drowsiness is associated with antral distension. On the average, drowsiness occurs late after meal ingestion and after the onset of gastrointestinal dyspeptic symptoms. The onset of postprandial drowsiness is usually preceded by an increment of antral distension and the duration of the symptom appears to be related to the persistence of antral distension. Finally, a delayed gastric emptying is significantly associated with postprandial drowsiness and the degree of the fasting antral volume.

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Kumar M E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Talley NJ, Stanghellini V, Heading RC, Koch KL, Malagelada JR, Tytgat GN. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gut. 1999;45 Suppl 2:II37-II42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 342] [Cited by in RCA: 415] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Talley NJ, Phillips SF, Bruce B, Zinsmeister AR, Wiltgen C, Melton LJ. Multisystem complaints in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1991;3:71-77. |

| 3. | Corinaldesi R, Stanghellini V, Raiti C, Rea E, Salgemini R, Barbara L. Effect of chronic administration of cisapride on gastric emptying of a solid meal and on dyspeptic symptoms in patients with idiopathic gastroparesis. Gut. 1987;28:300-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Distrutti E, Fiorucci S, Hauer SK, Pensi MO, Vanasia M, Morelli A. Effect of acute and chronic levosulpiride administration on gastric tone and perception in functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:613-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pallotta N, Pezzotti P, Calabrese E, Baccini F, Corazziari E. Relationship between gastrointestinal and extra-gastrointestinal symptoms and delayed gastric emptying in functional dyspeptic patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:4375-4381. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Piessevaux H, Tack J, Walrand S, Pauwels S, Geubel A. Intragastric distribution of a standardized meal in health and functional dyspepsia: correlation with specific symptoms. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2003;15:447-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Talley NJ, Shuter B, McCrudden G, Jones M, Hoschl R, Piper DW. Lack of association between gastric emptying of solids and symptoms in nonulcer dyspepsia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1989;11:625-630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Stanghellini V, Tosetti C, Paternico A, Barbara G, Morselli-Labate AM, Monetti N, Marengo M, Corinaldesi R. Risk indicators of delayed gastric emptying of solids in patients with functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1036-1042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 491] [Cited by in RCA: 453] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tack J, Piessevaux H, Coulie B, Caenepeel P, Janssens J. Role of impaired gastric accommodation to a meal in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1346-1352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 771] [Cited by in RCA: 762] [Article Influence: 28.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Boeckxstaens GE, Hirsch DP, van den Elzen BD, Heisterkamp SH, Tytgat GN. Impaired drinking capacity in patients with functional dyspepsia: relationship with proximal stomach function. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:1054-1063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Boeckxstaens GE, Hirsch DP, Kuiken SD, Heisterkamp SH, Tytgat GN. The proximal stomach and postprandial symptoms in functional dyspeptics. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:40-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Talley NJ, Verlinden M, Jones M. Can symptoms discriminate among those with delayed or normal gastric emptying in dysmotility-like dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1422-1428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Karamanolis G, Caenepeel P, Arts J, Tack J. Association of the predominant symptom with clinical characteristics and pathophysiological mechanisms in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:296-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ricci R, Bontempo I, La Bella A, De Tschudy A, Corazziari E. Dyspeptic symptoms and gastric antrum distribution. An ultrasonographic study. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1987;19:215-217. |

| 15. | Hausken T, Berstad A. Wide gastric antrum in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia. Effect of cisapride. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;27:427-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Marzio L, Falcucci M, Grossi L, Ciccaglione FA, Malatesta MG, Castellano A, Ballone E. Proximal and distal gastric distension in normal subjects and H. pylori-positive and -negative dyspeptic patients and correlation with symptoms. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:2757-2763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Salet GA, Samsom M, Roelofs JM, van Berge Henegouwen GP, Smout AJ, Akkermans LM. Responses to gastric distension in functional dyspepsia. Gut. 1998;42:823-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Loreno M, Bucceri AM, Catalano F, Muratore LA, Blasi A, Brogna A. Pattern of gastric emptying in functional dyspepsia. An ultrasonographic study. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:404-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Delgado-Aros S, Camilleri M, Cremonini F, Ferber I, Stephens D, Burton DD. Contributions of gastric volumes and gastric emptying to meal size and postmeal symptoms in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1685-1694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Agréus L, Svärdsudd K, Nyrén O, Tibblin G. Irritable bowel syndrome and dyspepsia in the general population: overlap and lack of stability over time. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:671-680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 459] [Cited by in RCA: 449] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Troncon LE, Bennett RJ, Ahluwalia NK, Thompson DG. Abnormal intragastric distribution of food during gastric emptying in functional dyspepsia patients. Gut. 1994;35:327-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lorena SL, Tinois E, Brunetto SQ, Camargo EE, Mesquita MA. Gastric emptying and intragastric distribution of a solid meal in functional dyspepsia: influence of gender and anxiety. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:230-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wells AS, Read NW, Idzikowski C, Jones J. Effects of meals on objective and subjective measures of daytime sleepiness. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1998;84:507-515. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Orr WC, Shadid G, Harnish MJ, Elsenbruch S. Meal composition and its effect on postprandial sleepiness. Physiol Behav. 1997;62:709-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Drossman DA, E Corazziari, Talley NJ, Thompson WG, Whitehead WE. The functional gastrointestinal Disorders: Diagnosis, Pathophysiology and Treatment: a multinational consensus. Mclean, VA, USA: Degnon Associates 2000; . |

| 27. | Bolondi L, Bortolotti M, Santi V, Calletti T, Gaiani S, Labò G. Measurement of gastric emptying time by real-time ultrasonography. Gastroenterology. 1985;89:752-759. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Ricci R, Bontempo I, Corazziari E, La Bella A, Torsoli A. Real time ultrasonography of the gastric antrum. Gut. 1993;34:173-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hveem K, Jones KL, Chatterton BE, Horowitz M. Scintigraphic measurement of gastric emptying and ultrasonographic assessment of antral area: relation to appetite. Gut. 1996;38:816-821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Benini L, Sembenini C, Heading RC, Giorgetti PG, Montemezzi S, Zamboni M, Di Benedetto P, Brighenti F, Vantini I. Simultaneous measurement of gastric emptying of a solid meal by ultrasound and by scintigraphy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2861-2865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Benini L, Sembenini C, Castellani G, Caliari S, Fioretta A, Vantini I. Gastric emptying and dyspeptic symptoms in patients with gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1351-1354. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Duan LP, Zheng ZT, Li YN. A study of gastric emptying in non-ulcer dyspepsia using a new ultrasonographic method. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1993;28:355-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research. London: Chapman and Hall 1991; . |

| 34. | Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. New York: John Wiley and sons Inc 1989; . |

| 35. | Stata Corp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 5.0. College Station: Stata Corporation 1997; . |

| 36. | Lee KJ, Vos R, Janssens J, Tack J. Differences in the sensorimotor response to distension between the proximal and distal stomach in humans. Gut. 2004;53:938-943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Caldarella MP, Azpiroz F, Malagelada JR. Antro-fundic dysfunctions in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1220-1229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Gilja OH, Hausken T, Wilhelmsen I, Berstad A. Impaired accommodation of proximal stomach to a meal in functional dyspepsia. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:689-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Jones MP, Roth LM, Crowell MD. Symptom reporting by functional dyspeptics during the water load test. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1334-1339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Montaño-Loza A, Schmulson M, Zepeda-Gómez S, Remes-Troche JM, Valdovinos-Diaz MA. Maximum tolerated volume in drinking tests with water and a nutritional beverage for the diagnosis of functional dyspepsia. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3122-3126. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Smith A, Ralph A, McNeill G. Influences of meal size on post-lunch changes in performance efficiency, mood, and cardiovascular function. Appetite. 1991;16:85-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Stahl ML, Orr WC, Bollinger C. Postprandial sleepiness: objective documentation via polysomnography. Sleep. 1983;6:29-35. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Wells AS, Read NW. Influences of fat, energy, and time of day on mood and performance. Physiol Behav. 1996;59:1069-1076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Parker BA, Sturm K, MacIntosh CG, Feinle C, Horowitz M, Chapman IM. Relation between food intake and visual analogue scale ratings of appetite and other sensations in healthy older and young subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58:212-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Harnish MJ, Greenleaf SR, Orr WC. A comparison of feeding to cephalic stimulation on postprandial sleepiness. Physiol Behav. 1998;64:93-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Stacher G, Bauer H, Steinringer H. Cholecystokinin decreases appetite and activation evoked by stimuli arising from the preparation of a meal in man. Physiol Behav. 1979;23:325-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Kapás L, Obál F, Opp MR, Johannsen L, Krueger JM. Intraperitoneal injection of cholecystokinin elicits sleep in rabbits. Physiol Behav. 1991;50:1241-1244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Wells AS, Read NW, Uvnas-Moberg K, Alster P. Influences of fat and carbohydrate on postprandial sleepiness, mood, and hormones. Physiol Behav. 1997;61:679-686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Jones KL, Doran SM, Hveem K, Bartholomeusz FD, Morley JE, Sun WM, Chatterton BE, Horowitz M. Relation between postprandial satiation and antral area in normal subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66:127-132. [PubMed] |

| 50. | Sturm K, Parker B, Wishart J, Feinle-Bisset C, Jones KL, Chapman I, Horowitz M. Energy intake and appetite are related to antral area in healthy young and older subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:656-667. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Samsom M, Verhagen MA, vanBerge Henegouwen GP, Smout AJ. Abnormal clearance of exogenous acid and increased acid sensitivity of the proximal duodenum in dyspeptic patients. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:515-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Schwartz MP, Samsom M, Smout AJ. Chemospecific alterations in duodenal perception and motor response in functional dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2596-2602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Lee KJ, Vos R, Janssens J, Tack J. Influence of duodenal acidification on the sensorimotor function of the proximal stomach in humans. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;286:G278-G284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |