Published online Jan 28, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i4.656

Revised: June 28, 2005

Accepted: July 20, 2005

Published online: January 28, 2006

The antibiotics, metronidazole and ciprofloxacin, are the first-line treatment for pouchitis. Patients who do not respond to antibiotics or conventional medications represent a major challenge to therapy. In this report, we have described a successful treatment of severe refractory pouchitis with a novel agent, rebamipide, known to promote epithelial cell regeneration and angiogenesis. A 27-year-old male with ileo-anal pouch surgery presented with worsening anal pain, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. The patient was diagnosed to have pouchitis and was given metronidazole together with betamethasone enema (3.95 mg/dose). However, despite this intensive therapy, the patient did not improve. On endoscopy, ulceration and inflammation were seen in the ileal pouch together with contact bleeding and mucous discharge. The patient was treated with rebamipide enema (150 mg/dose) twice a day for 8 wk without additional drug therapy. Two weeks after the rebamipide therapy, stool frequency started to decrease and fecal hemoglobin became negative at the 4th wk. At the end of the therapy, endoscopy revealed that ulcers in the ileal pouch had healed with no obvious inflammation. The effect of rebamipide enema was dramatic and was maintained throughout the 11-mo follow-up. The patient continued to be in remission. No adverse effects were observed during the treatment or the follow-up period. The sustained response seen in this case with severe and refractory pouchitis indicates that agents, which promote epithelial cell growth, angiogenesis and mucosal tissue regeneration, are potential therapeutic agents for the treatment of refractory colorectal lesions.

- Citation: Miyata M, Konagaya T, Kakumu S, Mori T. Successful treatment of severe pouchitis with rebamipide refractory to antibiotics and corticosteroids: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(4): 656-658

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i4/656.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i4.656

Ulcerative colitis is a debilitating inflammatory bowel disease that poorly responds to the current medical interventions with aminosalicylates, corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and more recently with novel biologicals. Patients who fail to respond to the mainstays of therapy until now have had limited options, but submit to colectomy[1]. Accordingly, proctocolectomy and ileo-anal pouch surgery (IPAA) have become the standard choices for curative resections in patients with ulcerative colitis who require surgical removal of the colorectum[1,2]. However, the majority of patients with curative resection subsequently develop complications including pouchitis which is the most frequent long-term complication after IPAA[2-4]. Pouchitis was first reported by Kock et al[5] in 1977 as a non-specific acute inflammation of the ileal reservoir in patients who had undergone proctocolectomy. Since then, pouchitis has become a widely recognized complication of restorative proctocolectomy.

The etiology of pouchitis is unknown, theories range from genetic susceptibility, bacterial overgrowth, ischemia, and fecal stasis to a recurrence of ulcerative colitis in the pouch, a missed diagnosis of Crohn’s disease, or possibly a novel third form of inflammatory bowel disease[6]. Some patients with suspected pouchitis may not have inflammation of the pouch, but rather, irritable pouch syndrome. Hence, endoscopic investigations with biopsy are essential to decide whether a patient has pouchitis or not. Indeed, the more commonly used scores like the pouch disease activity index incorporate both endoscopic and histologic criteria. Furthermore, unlike common inflammatory bowel disease in which numerous controlled clinical trials have been conducted and data have become available, very limited number of controlled trials, to our knowledge, have been conducted on pouchitis[7,8].

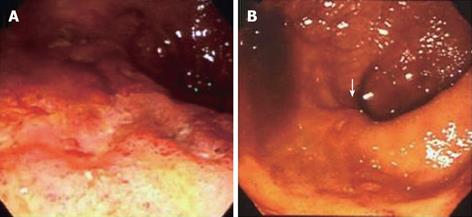

A 27-year-old male developed ulcerative colitis in 1992. He had been treated with conventional medications including corticosteroids. However, the ulcerative colitis had become refractory to conventional medication, and the patient therefore underwent total colectomy with mucosal proctocolectomy in 1993 and IPAA in 1994. In 1996, he presented with anal pain as well as protracted symptoms of diarrhea, abdominal pain, and incontinence which were worsening with time. The patient was diagnosed to have pouchitis and was treated with metronidazole together with betamethasone enema (3.95 mg/dose). However, despite this intensive therapy, the patient did not improve. In 2002, oral prednisolone (20 mg/dose) was given, and the patient improved for a few days. Then the patient’s symptoms went into a relapsing-remitting pattern with serum C-reactive protein (CRP) levels oscillating between 50 and 10 mg/L. On endoscopy in 2003, ulceration and inflammation were seen in the ileal pouch together with contact bleeding and mucous discharge (Figure 1A). After providing written informed consent, the patient was treated with rebamipide (2-(4-chlorobenzoylamino-3-[2 (1H)-quinolinon-4-yl]-propionic acid) enemas (150 mg/dose) twice a day for 8 wk without additional drug therapy.

Two weeks after the rebamipide therapy, stool frequency started to decrease and fecal hemoglobin became negative. Endoscopic findings showed that ulcers in the ileal pouch had healed with no obvious inflammation (Figure 1B). The effect of rebamipide enema was very dramatic and was maintained throughout the therapeutic period and the 11-mo follow-up. The patient continued to be in remission. No adverse effects were observed during the treatment or the follow-up period.

Although a recent Cochrane analysis had difficulty in identifying evidence-based support, the antibiotics, metronidazole and ciprofloxacin, are often used as the first-line treatment for pouchitis[4,6,9]. Some patients respond to this regimen and a smaller fraction respond to conventional medications with aminosalicylates, corticosteroids and immunomodulators. However, a proportion of patients with chronic pouchitis does not respond to any of these therapies and represent a major challenge to physicians. Thorough endoscopy reveals that mucosal damage (inflammation and ulcers) in refractory pouchitis and ulcerative colitis is similar. Therefore, substances that have both anti-inflammatory activity and promote epithelial cell growth (restore the integrity of the colonic mucosa and maintain its barrier function) should be effective in refractory pouchitis. In line with this thinking, we came to know a drug called rebamipide with striking potency to promote the epithelial cell growth factor (EGF) activity and EGF-receptor expression[10]. This prompted us to test its efficacy in a case of severe pouchitis, which did not respond to intensive conventional medication including antibiotics and corticosteroids.

The use of metronidazole in pouchitis is intended to inhibit colonization of the pouch by the bacteria which are suspected to be associated with the perpetuation of the disease in the pouch, as described for patients with an intact large bowel[11]. However, when the disease does not respond to metronidazole and conventional therapy for inflammatory bowel disease, it may respond to a novel medication like the response to rebamipide by the present refractory case. Rebamipide has a proven anti-ulcer effect in animal models of colitis[12]. Recently, it has been proposed that rebamipide activates in gastric epithelial cells a genetic program that promotes angiogenesis and signals cell growth and tissue regeneration[12,13].

Thus, both the actions of rebamipide, such as the anti-ulcer effect and the activation of epithelial cell regeneration, may be attributed to the efficacy in the present case of severe pouchitis.

S- Editor Wang XL and Guo SY L- Editor Elsevier HK E- Editor Bi L

| 1. | Hanauer SB. Medical therapy for ulcerative colitis 2004. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1582-1592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Braveman JM, Schoetz DJ, Marcello PW, Roberts PL, Coller JA, Murray JJ, Rusin LC. The fate of the ileal pouch in patients developing Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1613-1619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kuisma J, Järvinen H, Kahri A, Färkkilä M. Factors associated with disease activity of pouchitis after surgery for ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:544-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mahadevan U, Sandborn WJ. Diagnosis and management of pouchitis. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1636-1650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kock NG, Darle N, Hultén L, Kewenter J, Myrvold H, Philipson B. Ileostomy. Curr Probl Surg. 1977;14:1-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | West AB, Losada M. The pathology of diverticulosis coli. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:S11-S16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | McLeod RS, Taylor DW, Cohen Z, Cullen JB. Single-patient randomised clinical trial. Use in determining optimum treatment for patient with inflammation of Kock continent ileostomy reservoir. Lancet. 1986;1:726-728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Madden MV, McIntyre AS, Nicholls RJ. Double-blind crossover trial of metronidazole versus placebo in chronic unremitting pouchitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:1193-1196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gionchetti P, Morselli C, Rizzello F, Romagnoli R, Campieri M, Poggioli G, Laureti S, Ugolini F, Pierangeli F. Management of pouch dysfunction or pouchitis with an ileoanal pouch. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;18:993-1006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tarnawski A, Arakawa T, Kobayashi K. Rebamipide treatment activates epidermal growth factor and its receptor expression in normal and ulcerated gastric mucosa in rats: one mechanism for its ulcer healing action. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:90S-98S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cleary RK. Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea and colitis: clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:1435-1449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Arakawa T, Watanabe T, Fukuda T, Yamasaki K, Kobayashi K. Rebamipide, novel prostaglandin-inducer accelerates healing and reduces relapse of acetic acid-induced rat gastric ulcer. Comparison with cimetidine. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:2469-2472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tarnawski AS, Chai J, Pai R, Chiou SK. Rebamipide activates genes encoding angiogenic growth factors and Cox2 and stimulates angiogenesis: a key to its ulcer healing action. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:202-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |