Published online Jan 28, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i4.652

Revised: July 28, 2005

Accepted: August 3, 2005

Published online: January 28, 2006

We have reported a case of hepatic adenomatosis associated with hormone replacement therapy (estrogen and progesterone) and hemosiderosis caused by excessive blood transfusion for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. A 34-year-old woman was found to have several hepatic tumors on a routine medical examination. The general condition was good. Laboratory studies showed iron overload. Abdominal computed tomography and selective hepatic angiography showed several hypervascular tumors in the right lobe of the liver (up to 20 mm in diameter). Since hepatocellular carcinoma could not be ruled out, subsegmental hepatectomy was performed. Histopathological examination of the surgical specimen showed hepatic adenomatosis with hemosiderosis. Both hormone replacement therapy and iron overload could be the cause of hepatic adenomatosis.

- Citation: Hagiwara S, Takagi H, Kanda D, Sohara N, Kakizaki S, Katakai K, Yoshinaga T, Higuchi T, Nomoto K, Kuwano H, Mori M. Hepatic adenomatosis associated with hormone replacement therapy and hemosiderosis: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(4): 652-655

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i4/652.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i4.652

Hepatic adenoma is an uncommon benign liver tumor; however, its incidence increases in women of childbearing age because of its close relation to the usage of oral contraceptives[1]. Most patients start to develop hepatic adenoma after 5 years of usage of oral contraceptives[2]. Hepatic adenoma frequently regresses following discontinuation of oral contraceptives[3]. Hepatic adenoma also occurs in association with androgenic steroid use and with type I glycogen storage disease[4]; however, the mechanism of its occurrence is unknown. On the other hand, hepatic adenomatosis is characterized by the presence of multiple adenomas of various sizes in the liver and it has neither female predominance nor relation with estrogen/progesterone intake[5]. Thus, hepatic adenomatosis can be distinguished from hepatic adenoma.

Both hepatic adenoma and adenomatosis are frequently difficult to distinguish from well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). It has been reported that iron overload in the liver is occasionally associated with the development of both HCC and adenoma[6]. HCC develops in a variety of conditions associated with iron overload, particularly idiopathic hemochromatosis in which a 30% incidence has been reported[6]. Two cases of hepatic adenoma have been reported in patients with beta-thalassemia and secondary iron overload[7,8]. Furthermore, one case of hepatic adenoma has been reported in a patient with aplastic anemia treated with anabolic androgenic steroids and blood transfusions for 5 years[9]. Hepatic adenomatosis is also associated with hereditary hemochromatosis[10]. Based on these findings, iron overload seems to be involved in the hepatocarcinogenic process. While the mechanism of hepatic tumorigenesis in the presence of hemosiderosis is not understood, it is possible that the Fenton’s reaction generates free oxygen radicals that in turn cause DNA damage[11].

Here we have reported a case of hepatic adenomatosis complicated with hepatic hemosiderosis caused by excessive blood transfusion for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), followed by sex steroid hormone therapy for 8 years.

A 34-year-old woman was found to have four hepatic tumors by computed tomography (CT) on a routine medical check-up. At 22 years of age, she was diagnosed with CML. One year later, blast crisis occurred and she underwent allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT) from her daughter in addition to receiving total body irradiation (TBI) and several blood transfusions. She developed amenorrhea after TBI and started to receive hormone replacement therapy (estrogen and progesterone) from 26 years of age to maintain uterine and ovarian functions. She remained relatively healthy without recurrence of CML after BMT. However, liver tumors were found on regular examination 8 years after BMT.

She had no history of glycogen storage disease or usage of anabolic steroid. General physical examination was normal. Blood tests and urinalysis were normal except for elevated serum iron (2 810 µg/L and ferritin (2 508.2 μg/L). Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), anti-HBs antibody, and anti-hepatitis C virus antibody were negative. Serum alpha-fetoproteins (AFP), protein induced by the absence of vitamin K (PIVKA)-II, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and carbohydrate antigenic determinant (CA) 19-9 were within normal limits.

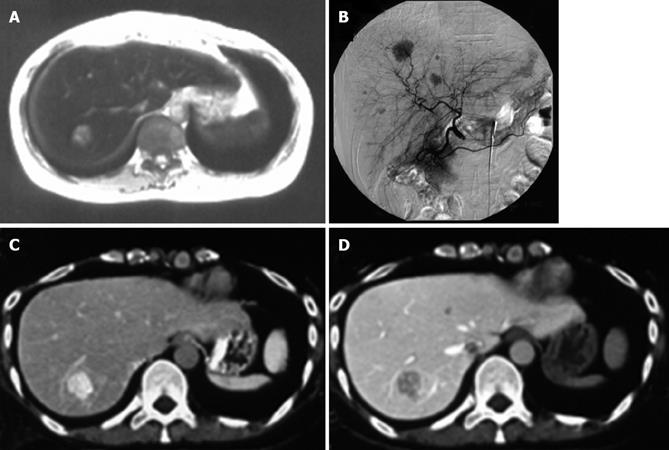

Abdominal ultrasonography (US) demonstrated an iso-echoic mass lesion measuring 2 cm in diameter located in the right posterior segment of the liver. Although US showed only one tumor, abdominal CT showed several low-density lesions (up to 2 cm in diameter) in the liver (segments 4, 5, 7, and 8 according to Couinaud’s classification). Dynamic CT revealed enhancement of the masses during arterial phase, which showed low-density lesions during portal venous phase. These abnormal masses in the liver were also detected as high-intensity on T1-weighed and iso-intensity on T2-weighed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Moreover, both T1-weighed and T2-weighed MRI showed decreased liver parenchymal intensities, suggestive of hemosiderosis (Figure 1A). Celiac angiography demonstrated multiple hypervascular mass lesions in the liver (segments 4, 5, 7, and 8) (Figure 1B). However, neither arteriovenous shunts nor vessel invasion were observed. CT during hepatic angiography (CTHA) showed these mass lesions with increased arterial supply, which reduced portal supply on CT during arterial portography (CTAP) (Figures 1C and 1D).

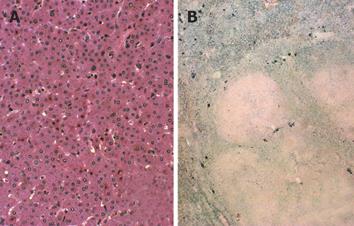

A tissue specimen of the tumor obtained by fine needle biopsy revealed monotonous growth of tumor cells, but no atypia was observed. Based on the above findings, the preoperative diagnosis was hepatic adenomatosis, although HCC could not be completely ruled out. Therefore, subsegmental hepatectomy for segment 7 was performed. The tumor was yellowish and well-defined without encapsulation. Microscopically, the tumor cells were mostly normal in size. Their nuclei were round and regular in size, and their cytoplasm was eosinophilic and partly clear. The tumor cells were arranged predominantly in a thin trabecular pattern without pseudo-glandular structures and no portal triad was observed in the tumor (Figure 2A). The non-tumorous part of the liver showed marked hepatocellular and reticuloendothelial hemosiderosis (Figure 2B). Several small nodules could also be seen in the normal parenchyma around the tumor. The pathological diagnosis was hepatic adenomatosis in hemosiderosis of the liver. The patient was advised to stop hormonal therapy and remained healthy during the follow-up. At 3 years after discontinuation of hormonal therapy, the residual tumors did not change in size as shown by CT.

We have described here a woman with hepatic adenomatosis who had not used oral contraceptives but received estrogen and progesterone for 8 years as hormone replacement therapy for early menopause caused by TBI. Baum et al[2] have reported that the incidence of hepatic adenoma has increased among women on the usage of oral contraceptives[1]. For example, about 90% of patients with hepatic adenoma had continuously taken oral contraceptives in the USA[12]. In contrast, hepatic adenoma is rare in Japan because of the lack of widespread use of oral contraceptives; the incidence of hepatic adenoma in Japanese women on oral contraceptives is about 5%[13]. On the other hand, hepatic adenomatosis is an extremely rare syndrome and defined as the presence of multiple (at least 10) adenomas in the liver. Flejou et al[5] have indicated that liver adenomatosis affects both men and women, and it is not related to the usage of oral contraceptives, usage of androgenic steroid and glycogen storage disease. Our case had not used oral contraceptives but had received estrogen and progesterone.

Differential diagnosis of hepatic adenomatosis from multiple hemangiomas, multifocal nodular hyperplasia, multifocal HCC, and hypervascular liver metastases is sometimes difficult[9]. In general, HCC shows a rapid progression resulting in the tumorous obstruction of the intrahepatic portal veins, and it is associated with increased serum AFP concentration and liver cirrhosis[1]. On the other hand, hepatic adenomatosis shows a slow progression[9], although it sometimes causes impaired liver function, hemorrhage, rupture, and malignant degeneration of the lesion[8,14]. In our case, it was difficult to make differential diagnosis of hepatic adenomatosis from HCC based on the clinical, radiological, and histological examinations. Therefore, subsegmental hepatectomy was performed. Histopathological examination of a large specimen showed non-encapsulated nodule of tumor cells arranged predominantly in a thin trabecular pattern without portal vein or bile ducts. Several small nodules were also seen in the normal parenchyma around the tumor. These findings were compatible with hepatic adenomatosis. The extratumorous parenchyma showed hemosiderosis in hepatocytes; however, no iron deposition was noted in the adenoma nodules.

The pathogenesis of hepatic adenomatosis remains unknown. Hepatocellular adenomas in beta-thalassemic patients with secondary iron overload have been reported[7,8]. The development of HCC is associated with a variety of iron overload states, particularly hemochromatosis[7]. Recently, a case with hepatic adenomatosis related to primary hemochromatosis was reported[10]. Based on these findings, iron overload might be involved in the development of hepatocarcinogenesis. Moreover, Kebapci et al[9] reported a patient with hepatic adenomatosis who developed blood transfusion-related hemosiderosis and had received anabolic steroids for the treatment of aplastic anemia. In this regard, elevated body iron stores is reported as a risk factor for the appearance of several tumors in human beings[15]. Furthermore, it is considered that estrogen stimulates iron uptake and metabolism in vivo and the interaction of estrogen metabolites and metal ions produces free radical damage[11,15]. Therefore, the relation between estrogen administration and hepatic hemosiderosis induced by secondary iron overload is likely involved in the development of hepatic adenomatosis in our case.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of hepatic adenomatosis associated with hormone replacement therapy and secondary hemosiderosis. Thus, our case represents a human prototype of liver tumor formation induced by excessive iron and administration of sex steroid. Iron overload and sex hormone therapy may act synergistically to enhance the development of liver adenomatosis.

Dr Masamichi Kojiro (Department of Pathology, Kurume University School of Medicine, Japan) for the useful advice on pathological diagnosis.

S- Editor Wang XL, Pan BR and Guo SY L- Editor Elsevier HK E- Editor Bi L

| 1. | Bühler H, Pirovino M, Akobiantz A, Altorfer J, Weitzel M, Maranta E, Schmid M. Regression of liver cell adenoma. A follow-up study of three consecutive patients after discontinuation of oral contraceptive use. Gastroenterology. 1982;82:775-782. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Baum JK, Bookstein JJ, Holtz F, Klein EW. Possible association between benign hepatomas and oral contraceptives. Lancet. 1973;2:926-929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 434] [Cited by in RCA: 356] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Steinbrecher UP, Lisbona R, Huang SN, Mishkin S. Complete regression of hepatocellular adenoma after withdrawal of oral contraceptives. Dig Dis Sci. 1981;26:1045-1050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Brophy CM, Bock JF, West AB, McKhann CF. Liver cell adenoma: diagnosis and treatment of a rare hepatic neoplastic process. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:429-432. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Flejou JF, Barge J, Menu Y, Degott C, Bismuth H, Potet F, Benhamou JP. Liver adenomatosis. An entity distinct from liver adenoma. Gastroenterology. 1985;89:1132-1138. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Powell LW, Bassett ML, Halliday JW. Hemochromatosis: 1980 update. Gastroenterology. 1980;78:374-381. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Cannon RO, Dusheiko GM, Long JA, Ishak KG, Kapur S, Anderson KD, Nienhuis AW. Hepatocellular adenoma in a young woman with beta-thalassemia and secondary iron overload. Gastroenterology. 1981;81:352-355. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Shuangshoti S, Thaicharoen A. Hepatocellular adenoma in a beta-thalassemic woman having secondary iron overload. J Med Assoc Thai. 1994;77:108-112. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Kebapci M, Kaya T, Aslan O, Bor O, Entok E. Hepatic adenomatosis: gadolinium-enhanced dynamic MR findings. Abdom Imaging. 2001;26:264-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Radhi JM, Loewy J. Hepatocellular adenomatosis associated with hereditary haemochromatosis. Postgrad Med J. 2000;76:100-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wyllie S, Liehr JG. Release of iron from ferritin storage by redox cycling of stilbene and steroid estrogen metabolites: a mechanism of induction of free radical damage by estrogen. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;346:180-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Craig JR, PetersRL , Edmondson HA. Benign epithelial tumors and tumor like conditions. Atlas of Tumor Pathology. 2nd series, Fascicle 26, Washington D.C. : Armed Forces Institute of Pathology 1989; pp8-61. |

| 13. | Konishi M, Ryu M, Kinoshita T, Kawano N, Hasebe T, Mukai K. A case report of liver cell adenoma. Acta Hepatol Jpn 36: 223-229. 1995;. |

| 14. | Grazioli L, Federle MP, Ichikawa T, Balzano E, Nalesnik M, Madariaga J. Liver adenomatosis: clinical, histopathologic, and imaging findings in 15 patients. Radiology. 2000;216:395-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liehr JG, Jones JS. Role of iron in estrogen-induced cancer. Curr Med Chem. 2001;8:839-849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |