Published online Jan 28, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i4.649

Revised: June 8, 2005

Accepted: June 24, 2005

Published online: January 28, 2006

Duodenal Crohn’s disease is rare, and patients without obstruction are treated medically. We herein report one case whose duodenal Crohn’s disease was successfully managed with low-speed elemental diet infusion through a nasogastric tube. A 28-year-old female developed acute duodenal Crohn’s disease. Upper GI radiologic and endoscopic examinations showed a stricture in the duodenal bulb. Using the duodenal biopsy specimens, mucosal cytokine levels were measured; interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor-α levels were remarkably elevated. For initial 2 wk, powdered mesalazine was orally given but it was not effective. For the next 2 wk, she was treated with low-speed elemental diet therapy using a commercially available ElentalTM, which was infused continuously through a nasogastric tube using an infusion pump. The tip of the nasogastric tube was placed at an immediate oral side of the pylorus. The infusion speed was 10 mL/h (usual speed, 100 mL/h). After the 2-wk treatment, her symptoms were very much improved, and endoscopically, the duodenal stricture and inflammation improved. The duodenal mucosal cytokine levels remarkably decreased compared with those before the treatment. Although our experience was limited, low-speed elemental diet infusion through a nasogastric tube may be a useful treatment for acute duodenal Crohn’s disease.

- Citation: Yamamoto T, Nakahigashi M, Umegae S, Kitagawa T, Matsumoto K. Acute duodenal Crohn’s disease successfully managed with low-speed elemental diet infusion via nasogastric tube: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(4): 649-651

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i4/649.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i4.649

The frequency of duodenal Crohn’s disease is rare, and is reported to range between 0.5% and 5.0% in Crohn’s disease[1-3]. Duodenal Crohn’s disease is almost invariably present in association with the disease elsewhere in the intestinal tract. Medical therapy for distal disease may mask the symptoms of duodenal disease and delay its diagnosis. The most common site of duodenal Crohn’s disease is the duodenal bulb, and stricture is the most common pathology[1-3]. Medical therapy including H2-receptor antagonists, 5-aminosalicylic acid, corticosteroids, and immunosuppressive drugs is effective for patients having duodenal strictures without obstruction; however, surgery is necessary for patients with obstruction[1-3].

Cytokines are involved in the modulation of the immune system related to the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease, such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, and they are rapidly synthesized and secreted by inflammatory cells[4,5]. In our previous study, we found that elemental diet therapy markedly improved clinical symptoms, and reduced the mucosal cytokine production in patients with ileal or colonic Crohn’s disease[6]. Recently, we experienced one case whose duodenal Crohn’s disease was successfully managed with low-speed elemental diet infusion through a nasogastric tube.

In June 2000, a 23-year-old female presented with abdominal pain and diarrhea, and she was diagnosed as having Crohn’s disease in the terminal ileum. Thereafter, she was treated with corticosteroid (prednisolone, 5-20 mg/d) and mesalazine (Pentasa, 3.0 g/d). Despite the medical treatment, she required an operation (terminal ileal resection) in April 2002. After the initial operation, she was taking mesalazine (Pentasa, 3.0 g/d) to prevent recurrence. She started an enteral nutritional therapy using elemental diet, but could not continue the treatment. She developed abdominal pain and diarrhea due to recurrent ileal Crohn’s disease, but she refused to receive any steroids or immunosuppressive drugs. In June 2003, she underwent reoperation (ileal resection). Thereafter, she was treated with mesalazine (Pentasa, 3.0 g/d).

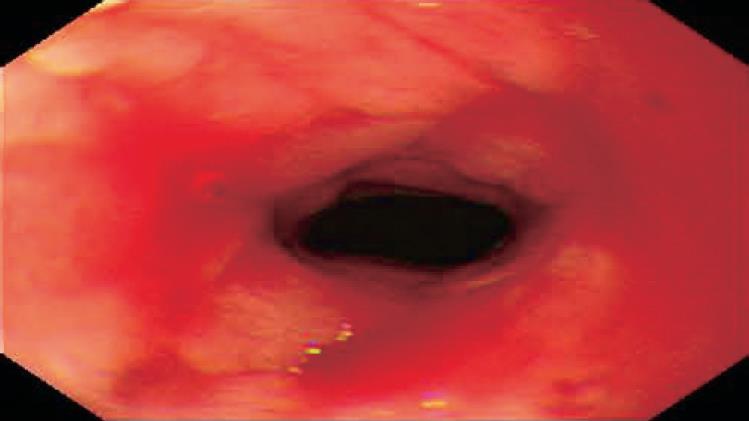

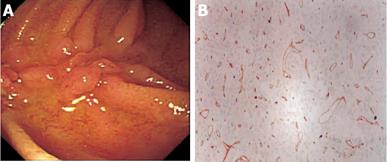

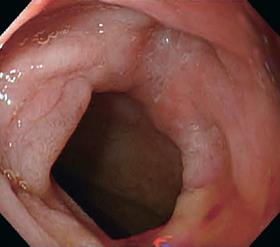

In March 2005, she developed severe postprandial upper abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Upper GI barium study showed a stricture of the duodenal bulb (Figure 1). Endoscopic examination revealed the stricture with mucosal edema and contact bleeding in the duodenal bulb (Figure 2A). The endoscope could be inserted into the second part of the duodenum, where the longitudinal ulcerations were observed (Figure 2B). The gastric mucosa was moderately inflamed but there were no ulcerations in the stomach. Histologically, the biopsy specimens of the duodenal bulb showed severe inflammation with the accumulation of a large amount of inflammatory cells. Granulomas were not detected. Using the duodenal biopsy specimens, mucosal cytokine levels were measured by the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as previously reported[6]. The cytokine measurement was performed after the clinical data has been recorded. Laboratory investigators were blind to the clinical data. Interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α levels were remarkably elevated compared with those in patients without any gastroduodenal diseases (normal control) (Table 1). She was diagnosed with acute duodenal Crohn’s disease, and was hospitalized in our unit. At admission, the main results of blood examinations were: white blood cell count, 5.6×109 (normal, 3.5×109-9×109)/L; hemoglobin, 99 (normal, 115-160) g/L; platelet count, 542×109 (normal, 130×109-370×109)/L; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 9 (normal, ≤ 15) mm/h; C-reactive protein, 4.5 (normal, ≤4) mg/L; and albumin, 29 (normal, ≥ 40) g/L. Because she could not take any foods and her nutritional status was poor, she was managed with total parenteral nutrition (approximately 8 368 kJ/d) after the admission. H2-receptor antagonist (famotidine; Gaster, 40 mg/d) was intravenously administered for 4 wk. For initial 2 wk after the admission, powdered mesalazine (Pentasa, 1 g) was orally given three times a day. However, her symptoms were not improved, and repeat endoscopic examination also revealed no improvement. For the next 2 wk, she was treated with low-speed elemental diet infusion therapy. The enteral formula was a commercially available ElentalTM (Ajinomoto and Morishita-Russel, Tokyo, Japan), which is composed of amino acids, very little fat, vitamins, trace elements and a major energy source, dextrin. The details of ElentalTM were reported in our previous paper[6]. The elemental formula was infused continuously through a silicone-elastomer nasogastric tube using an infusion pump. The tip of the nasogastric tube was placed at an immediate oral side of the pylorus, which was confirmed radiologically. The infusion speed was 10 mL/h (usual speed for this enteral formula is approximately 100 mL/h). After the 2-wk treatment, her symptoms were very much improved, and endoscopic examination also revealed improvement of the duodenal stricture and inflammation (Figure 3). The longitudinal ulcerations in the second part of the duodenum also improved but they did not normalize. The duodenal mucosal IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α levels also remarkably decreased compared with those before the elemental diet therapy (Table 1). At present, she is taking low residue and low fat foods in the daytime according to the instructions of her dietician, and in the night-time, the elemental diet is infused through a self-intubated nasogastric tube using an infusion pump with an increased speed (100 mL/h).

| Tissue cytokine(ng/g) | Beforetreatment | Aftertreatment | Normal control1median value (range) |

| IL-1β | 370 | 45 | 12 (0-23) |

| IL-6 | 12 000 | 570 | 220 (70-280) |

| IL-8 | 450 | 30 | 20 (0-36) |

| TNF-α | 310 | 24 | 14 (0-21) |

In this study, our patient refused to receive any steroids or immunosuppressive drugs in the management of Crohn’s disease. Initially, powdered mesalazine (Pentasa, 3 g/d) was not effective for her duodenal Crohn’s disease. We, therefore, decided to try our elemental diet therapy because there seemed to be no other useful medical treatment. The tip of the nasogastric tube was carefully placed at an immediate oral side of the pylorus. The elemental formula was infused continuously with a low speed (10 mL/h) for 2 wk because the duodenal bulb was obstructive. During the treatment, our patient did not have increased abdominal pain, nausea or vomiting. The aim of this therapy was to reduce the mucosal inflammation using the elemental diet, but not to improve the nutritional status of the patient. The enteral formula infused through the nasogastric tube continuously stayed at the site of the duodenal stricture. Eventually, this treatment remarkably reduced proinflammatory cytokine production in the duodenal mucosa. Clinical and endoscopic improvements were associated with a decline in the mucosal cytokine production. However, from our experience, the elemental diet is useful only for bowel strictures due to acute mucosal inflammation (edema). Generally, the tight fibrotic strictures require surgical treatment in patients with Crohn’s disease.

In our previous prospective study[6], 28 patients with active ileal or colonic Crohn’s disease were treated with ElentalTM for 4 wk. The mucosal biopsies were obtained from the terminal ileum and large bowel before and after the treatment. After the treatment, clinical remission was achieved in 71% of patients. Endoscopic healing and improvement rates were 44% and 76% in the terminal ileum and 39% and 78% in the large bowel, respectively. The mucosal concentrations of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α in the ileum and large bowel were increased before the treatment; however, these cytokine levels decreased to the levels of normal control after the treatment. Other studies also examined the relationship between the mucosal cytokine production and enteral nutrition using different formulas, and they reported similar results to that of ours[7,8]. Breese et al[7] investigated the proportion of lymphokine (IL-2 and interferon-γ)-secreting cells in the intestinal mucosa of patients with Crohn’s disease treated with either enteral nutrition or cyclosporine therapy. Enteral nutrition produced a reduction in lymphokine-secreting cells equivalent to cyclosporine therapy, and it produced better clinical improvement. Fell et al[8] examined 29 children with active Crohn’s disease treated with an oral polymeric diet. Macroscopic mucosal healing in the terminal ileum and colon was associated with a decline in ileal and colonic IL-1β levels. The detailed mechanism of elemental diet on immunological reactions in Crohn’s disease remains unknown. The main mechanisms may be removal of food antigen and decreases of bowel secretion and motility induced by very low fat content. However, further investigations are necessary.

Our low-speed elemental diet infusion therapy through a nasogastric tube was useful to improve acute duodenal Crohn’s disease without any adverse effects. Although our experience was limited, this therapy may be a preferable treatment for acute duodenal Crohn’s disease because patients can be treated without steroids or immunosuppressive drugs.

S- Editor Kumar M, Pan BR and Guo SY L- Editor Elsevier HK E- Editor Bai SH

| 1. | Farmer RG, Whelan G, Fazio VW. Long-term follow-up of patients with Crohn's disease. Relationship between the clinical pattern and prognosis. Gastroenterology. 1985;88:1818-1825. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Nugent FW, Roy MA. Duodenal Crohn's disease: an analysis of 89 cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:249-254. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Yamamoto T, Allan RN, Keighley MR. An audit of gastroduodenal Crohn disease: clinicopathologic features and management. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:1019-1024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Reinecker HC, Steffen M, Witthoeft T, Pflueger I, Schreiber S, MacDermott RP, Raedler A. Enhanced secretion of tumour necrosis factor-alpha, IL-6, and IL-1 beta by isolated lamina propria mononuclear cells from patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 1993;94:174-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 603] [Cited by in RCA: 648] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rogler G, Andus T. Cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Surg. 1998;22:382-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 373] [Cited by in RCA: 385] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yamamoto T, Nakahigashi M, Umegae S, Kitagawa T, Matsumoto K. Impact of elemental diet on mucosal inflammation in patients with active Crohn's disease: cytokine production and endoscopic and histological findings. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:580-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Breese EJ, Michie CA, Nicholls SW, Williams CB, Domizio P, Walker-Smith JA, MacDonald TT. The effect of treatment on lymphokine-secreting cells in the intestinal mucosa of children with Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9:547-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fell JM, Paintin M, Arnaud-Battandier F, Beattie RM, Hollis A, Kitching P, Donnet-Hughes A, MacDonald TT, Walker-Smith JA. Mucosal healing and a fall in mucosal pro-inflammatory cytokine mRNA induced by a specific oral polymeric diet in paediatric Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:281-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 300] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |