Published online Oct 7, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i37.6077

Revised: July 3, 2006

Accepted: July 7, 2006

Published online: October 7, 2006

We report a case of sigmoid colonic carcinoma associated with deposited ova of Schistosoma japonicum. A 57-year old woman presented with a 10-mo history of left lower quadrant abdominal pain and a 2-mo history of bloody stools. She had a significant past medical history of asymptomatic schistosomiasis japonica and constipation. A colonoscopy showed an exophytic fragile neoplasm with an ulcerating surface in the sigmoid colon. During the radical operative procedure, we noted the partially encircling tumor was located in the distal sigmoid colon, and extended into the serosa. Succedent pathological analysis demonstrated the diagnosis of sigmoid colonic ulcerative tubular adenocarcinoma, and showed deposited ova of Schistosoma japonicum in both tumor lesions and mesenteric lymph nodes. Three days after surgery the patient returned to the normal bowel function with one defecation per day. These findings reveal that deposited schistosome ova play a possible role in the carcinogenesis of colorectal cancer.

- Citation: Li WC, Pan ZG, Sun YH. Sigmoid colonic carcinoma associated with deposited ova of Schistosoma japonicum: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(37): 6077-6079

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i37/6077.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i37.6077

Schistosomiasis is a trematode parasitic infection in which terminal hosts are humans or other mammals with freshwater snails as intermediate hosts[1]. Schistosomiasis japonica is endemic mainly in China, and remains a major public health problem today although remarkable successes in schistosomiasis control have been achieved over the previous four decades[2].

The life cycle of Schistosoma japonicum (S. japonicum) starts when cercariae in the freshwater infect humans or other mammals. After maturing, male and female worms pair up in the hepatic portal vein system, and produce ova in the mucosal branches of the inferior mesenteric and superior hemorrhoidal veins. Many ova are discharged in the feces, hatch, and release free-swimming miracidia, which in turn reinfect receptive freshwater snails and asexually produce larval cercariae[2]. However, some ova deposit in the tissues of the host, cause host inflammatory responses, and lead to granuloma formation which is the principal pathology associated with schistosomiasis[3]. Periovular granulomas have been found in many types of tissue, including the liver, intestine, skin, lung, brain, adrenal glands, and skeletal muscle. Ova retained in the gut wall induce inflammation, hyperplasia, ulceration, microabscess formation, polyposis, and carcinogenesis[3].

Successes in schistosomiasis control in China have prolonged the life of patients with schistosomiasis japonica in which the chronic pathological process may occur due to deposited schistosome ova.

Here we report a case of sigmoid colonic carcinoma associated with deposited ova of S. japonicum, with their possible role in carcinogenesis discussed.

A 57-year old woman presented with a 10-mo history of left lower quadrant abdominal pain and a 2-mo history of bloody stools. She had a sense of pain in the left lower quadrant abdomen when she had bowel movements about 10 mo ago. The pain was relieved after defecation, so that she did not think much of it. Two months ago, she noted that dark red blood adhered to the surface of stools without blood drops from anus. The symptom of hematochezia persisted until hospitalization. She had no other complaints. She had a significant past medical history of asymptomatic schistosomiasis japonica and constipation. She came from the rural area in Zhejiang Province, where schistosomiasis japonica was prevalent several decades ago. She had the experience of swimming in a local river in her childhood. At the age of 13, she was diagnosed with schistosomiasis through a thick smear stool examination by the county public health workers for schistosomiasis control, and given the appropriate antischistosomiasis therapy which was not terminated until repeated stool examinations were negative. At the age of 20, she suffered from constipation which was not improved by adequate fiber intake. Usually, she had about two bowel movements with hard stools per week. The symptom began to become worse ten years ago and she had defecation once per week.

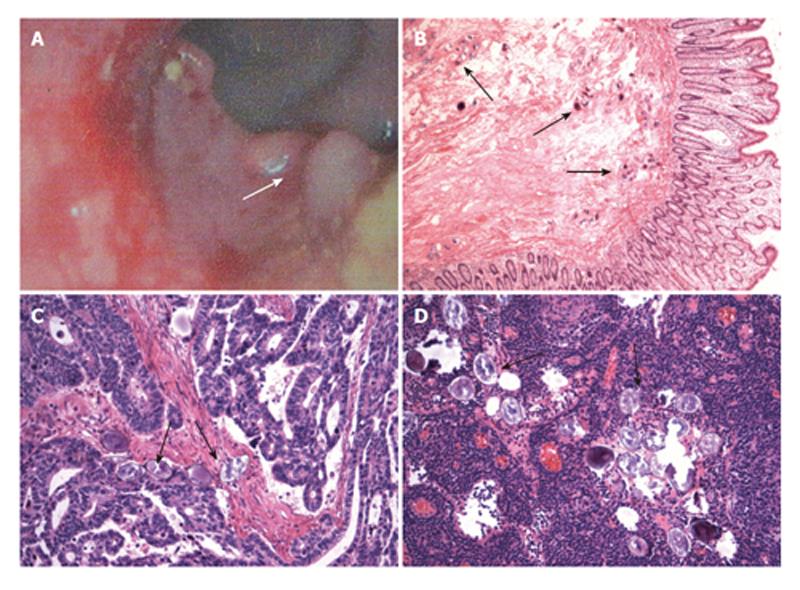

She was in good general condition. No supraclavicular lymph nodes were palpable. On abdominal palpation, there was a discomfortable sense in the left lower quadrant without palpable masses. Her peripheral blood cell count showed leucopenia (white blood cells: 3100/mm3) and mild thrombocytopenia (platelets: 72 000/mm3), without anemia and eosinophilia. Three stool tests were all negative for S. japonicum ova. Liver function, renal function and electrocyte concentration were all normal. Tumor markers (AFP, CEA, and CA-199) were 2.41 ng/mL, 0.72 ng/mL, and 5.88 U/mL, respectively, which were within normal limits. The abdominal ultrasonography revealed echodense areas scattered within the parenchyma with typical fish-scale pattern, representing the trait of liver schistosomiasis. The computed tomographic scan showed that the bowel wall of sigmoid colon was incrassated and irregular in shape. The colonoscopy showed an exophytic fragile neoplasm with an ulcerating surface in the sigmoid colon (Figure 1A), which was diagnosed as adenocarcinoma through biopsy.

After definite diagnosis was made, the radical operative procedure was performed. During laparotomy, the entire peritoneal cavity was examined, with a thorough inspection of the liver, pelvis, and hemidiaphragm. Neither metastatic lesions nor enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes were found. The partially encircling tumor was located in the distal sigmoid colon, and extended into the serosa. Pathological analysis of the operative specimen revealed deposited S. japonicum ova, granuloma formation, and fibrotic deposition in the submucosa of the sigmoid colon (Figure 1B), and demonstrated a grade 2 moderately-differentiated sigmoid colonic ulcerative tubular adenocarcinoma, 3 cm × 2 cm in size, penetrating the serosa without lymph node involvement (Figure 1C). Deposited S. japonicum ova were found in both tumor lesions (Figure 1C) and mesenteric lymph nodes (Figure 1D).

Three days after surgery the patient returned to the normal bowel function with one defecation per day.

The relation between colorectal cancer and schistosomiasis japonica has not been well established. However, researchers in China have noted the coincidence of colon cancer and schistosomiasis japonica at the patient level during the 1970s[4]. Another case-control study in Jiangsu Province showed that rectal cancer is associated with schistosomiasis japonica[5]. A recent matched case-control study showed that previous S. japonicum infection is significantly associated with both liver cancer and colon cancer[6]. It was also reported that schistosomiasis japonica correlates with colorectal cancer [7].

The mechanism of schistosome infection-induced colorectal cancer was explored in our study. The mutations in p53 tumor suppressor gene in Chinese patients with schistosomiasis japonica-related rectal cancer and a high proportion of base-pair substitutions at CpG dinucleotides and a higher frequency of arginine missense mutations were observed, suggesting that the mutations are the result of genotoxic agents produced endogenously through the course of schistosomiasis japonica[8]. Another study showed that S. japonicum ova-induced colorectal epithelial proliferative polyps have a high percentage of atypical hyperplasia (64.9%) and CEA (90%)[9]. Thus the epithelial proliferative polyp, especially that with atypical hyperplasia, is the transition during deposited ova-induced carcinogenesis. It was reported that the majority of colorectal cancer cases associated with Schistosoma mansoni (S. mansoni) infection have a significant expression of Bcl-2 while p53 and C-Myc expressions are insignificantly different in colorectal cancer cases associated with S. mansoni infection compared with those without S. mansoni infection[10]. In a word, the mechanism of schistosome infection-induced carcinogenesis remains unclear.

In our present case, both chronic constipation and sigmoid colonic adenocarcinoma were induced by deposited S. japonicum ova, revealing that ova can interact with the host microenvironment. Asymptomatic schistosomiasis in our patient was cured as neither eosinophilia nor ova in her stools were observed. However, many old ova deposited in sigmoid colonic submucosa, tumor lesions, and mesenteric lymph nodes. Furthermore, the anatomic location of adenocarcinoma corresponded to the colorectal area with most deposited ova. These findings indicate that deposited S. japonicum ova play a possible role in the carcinogenesis of colorectal cancer[7].

Another important aspect of this case is that chronic constipation was improved after operation. In this case, granuloma formation and fibrotic deposition around deposited ova perhaps disturbed the sensory function of the sigmoid colon, and resulted in constipation.

Additionally, we noted deposited ova in the mesenteric lymph nodes, leucopenia, and thrombocytopenia in this case. However, their pathological significance remains unclear.

In conclusion, sigmoid colonic carcinoma is associated with deposited ova of S. japonicum. Therefore, screening for colorectal cancer should always be thoroughly performed with routine endoscopy in patients with previous S. japonicum infection, and the mechanism of deposited S. japonicum ova-induced carcinogenesis should be further investigated.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Wu GY, Halim MH. Schistosomiasis: progress and problems. World J Gastroenterol. 2000;6:12-19. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Ross AG, Sleigh AC, Li Y, Davis GM, Williams GM, Jiang Z, Feng Z, McManus DP. Schistosomiasis in the People's Republic of China: prospects and challenges for the 21st century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:270-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ross AG, Bartley PB, Sleigh AC, Olds GR, Li Y, Williams GM, McManus DP. Schistosomiasis. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1212-1220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 706] [Cited by in RCA: 651] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zhao ES. Cancer of the colon and schistosomiasis. J R Soc Med. 1981;74:645. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Xu Z, Su DL. Schistosoma japonicum and colorectal cancer: an epidemiological study in the People’s Republic of China. Int J Cancer. 1984;34:315-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Qiu DC, Hubbard AE, Zhong B, Zhang Y, Spear RC. A matched, case-control study of the association between Schistosoma japonicum and liver and colon cancers, in rural China. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2005;99:47-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Matsuda K, Masaki T, Ishii S, Yamashita H, Watanabe T, Nagawa H, Muto T, Hirata Y, Kimura K, Kojima S. Possible associations of rectal carcinoma with Schistosoma japonicum infection and membranous nephropathy: a case report with a review. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1999;29:576-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhang R, Takahashi S, Orita S, Yoshida A, Maruyama H, Shirai T, Ohta N. p53 gene mutations in rectal cancer associated with schistosomiasis japonica in Chinese patients. Cancer Lett. 1998;131:215-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yu XR, Chen PH, Xu JY, Xiao S, Shan ZJ, Zhu SJ. Histological classification of schistosomal egg induced polyps of colon and their clinical significance. An analysis of 272 cases. Chin Med J (Engl). 1991;104:64-70. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Zalata KR, Nasif WA, Ming SC, Lotfy M, Nada NA, El-Hak NG, Leech SH. p53, Bcl-2 and C-Myc expressions in colorectal carcinoma associated with schistosomiasis in Egypt. Cell Oncol. 2005;27:245-253. [PubMed] |