Published online Aug 7, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i29.4757

Revised: March 28, 2006

Accepted: April 21, 2006

Published online: August 7, 2006

A 29-year-old nurse with a hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection caused by needle-stick injury was treated with interferon-beta starting about one year after the onset of acute hepatitis. The patient developed acute hepatitis C with symptoms of general fatigues, jaundice, and ascites 4 wk after the needle-stick injury. When these symptoms were presented, the patient was pregnant by artificial insemination. She hoped to continue her pregnancy. After delivery, biochemical liver enzyme returned to normal levels. Nevertheless, HCV RNA was positive and the pathological finding indicated a progression to chronicity. The genotype was 1b with low viral load. Daily intravenous injection of interferon-beta at the dosage of six million units was started and continued for eight weeks. HCV was eradicated without severe adverse effects. In acute hepatitis C, delaying therapy is considered to reduce the efficacy but interferon-beta therapy is one of the useful treatments for hepatitis C infection in chronic phase.

- Citation: Kogure T, Ueno Y, Kanno N, Fukushima K, Yamagiwa Y, Nagasaki F, Kakazu E, Matsuda Y, Kido O, Nakagome Y, Ninomiya M, Shimosegawa T. Sustained viral response of a case of acute hepatitis C virus infection via needle-stick injury. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(29): 4757-4760

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i29/4757.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i29.4757

Needle-stick injury is a major cause of acute hepatitis C in health care workers[1]. Acute infection of hepatitis C virus (HCV) frequently progresses to chronic hepatitis, which leads to liver cirrhosis and to hepatocellular carcinoma[2]. Preventing the progress to chronicity is necessary, and several treatment strategies of interferon therapies were reported[3,4,5,6]. Early phase treatment is recommended in order to obtain a sustained virological response (SVR)[5]. On the other hand, optimal timing of treatment is controversial because self-limited hepatitis exists in 15%-30% of acute hepatitis C[7]. Several predictive factors of the spontaneous clearance of HCV were reported but these have not been confirmed in larger numbers and well-designed prospective studies. As wait & see strategy to expect the spontaneous viral clearance, it was reported that 8 to 12 wk of delaying therapies obtained more than 90% of SVR rate, however, a delay by one year reduced the rate[7,8]. We report a case of acute hepatitis C infection caused by needle-stick injury just before pregnancy. After delivery, the patient achieved a SVR by treating with interferon-beta in the chronic phase of acute hepatitis C.

The patient was a 29-year old Japanese woman. She was a clinical nurse. She had a missed abortion at the age of 26. She admitted occasional alcohol intake but she did not receive blood transfusions or operations.

She encountered a skin puncture on the hand from a needle contaminated with blood from a patient with chronic hepatitis C on September 15th, 2001. She became pregnant through artificial insemination on October 2nd. She felt general fatigue from October 16th. Her attending physician pointed out the abnormal liver function tests, and then she was referred to Sendai City Medical Center at October 19th. On admission, liver function tests indicated elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST; 549 IU/L, normal 12-30 IU/L) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT; 870 IU/L, normal 8-35 IU/L) activities. Total bilirubin (1.0 mg/dL, normal 0.2-1.2 mg/dL), albumin (39 g/L, normal 42-53 g/L), and prothrombin time (PT; 93%) indicated that hepatic functional reserve was maintained (Table 1). Anti-HCV antibody which was negative before the pregnancy, converted to positive, and HCV RNA test revealed high viral load with genotype 1b. Therefore, she was diagnosed with acute hepatitis C. A small amount of ascites was detected on the surface of the liver by ultrasound imaging.

| WBC | 6530 /μL | T-Bil | 1.0 mg/dL | HCV-Ab | positive |

| Hb | 13.0 g/μL | D-Bil | 0.7 mg/dL | HCV-RNA | > 850 kIU/L |

| Plt | 200 x 103 /μL | Total protein | 71 g/L | HCV genotype | 1b |

| PT | 93% | Albumin | 39 g/L | HAV IgM | negative |

| AST | 549 IU/L | BUN | 6.4 mg/dL | HBs-Ag | negative |

| ALT | 870 IU/L | Creatinine | 0.5 mg/dL | HBs-Ab | negative |

| LDH | 497 IU/L | Na | 140 mEq/L | IgM HBc-Ab | negative |

| ALP | 181 IU/L | K | 4.0 mEq/L | EBV IgM | negative |

| γ-GTP | 259 IU/L | Cl | 106 mEq/L | HSV IgM | negative |

| ChE | 94 IU/l | Glucose | 92 mg/dL | CMV IgM | negative |

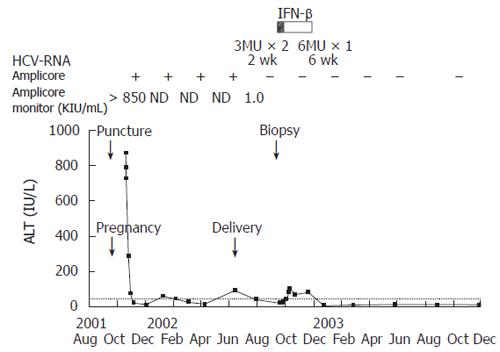

She hoped for continuation of the pregnancy, thus, conservative medical management was performed and liver function tests improved (Figure 1). After that, HCV RNA decreased below detection sensitivity of the routine quantitative method (Cobas Amplicor HCV Monitor test, Roche Diagnostic Systems, Branchburg, NY, USA) although remaining positive with qualitative method (Cobas Amplicor HCV test, Roche). On June 17th, 2002, she delivered safely. Liver function tests were within normal ranges but HCV RNA still remained positive. At this point, spontaneous viral clearance was not expected, thus, she was admitted to our hospital to receive anti-viral therapy on September 9th 2002.

Physical examination revealed: height 158 cm; weight 54 kg; blood pressure 118/64 mmHg; body temperature 36.3°C; and clear consciousness. The bulber conjunctiva was not icteric. No peripheral edema, vascular spider, and flapping tremor were observed.

The result demonstrated normal liver function, no evidence of coagulopathy, anemia, or thrombocytopenia. HCV RNA indicated 1.0 kIU/L, which was under detection sensitivity previously.

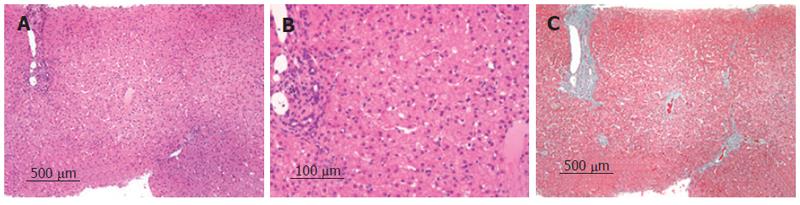

A liver biopsy specimen taken before anti-viral therapy demonstrated chronic hepatitis with mild activity without fibrosis. Swollen Kupffer cells were seen in diastase-periodic acid-Schiff preparations (Figure 2).

After informed consent was obtained, the patient received six million units of interferon-beta (Mochida Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) by intravenous drug injection daily for eight weeks. She developed a daily fever after the initiation of treatment but recovered in a brief period of time. Other adverse effects were not seen during the treatment. HCV RNA became negative two weeks after the initiation of treatment (Figure 1). ALT increased in slight degree but improved after the end of the treatment (Figure 1). HCV RNA negativity and normalization of ALT level were sustained for 40 mo after the end of interferon treatment.

In Japan, 85% of hepatocellular carcinoma patients are associated with chronic HCV infection[9]. Thus, to inhibiting the progression of acute HCV infection to chronicity is very important for the prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma. Recently, as the cause of post-transfusion hepatitis, HCV infection decreased to extremely low levels because of the establishment of diagnostic methods such as HCV-antibody or HCV RNA detection[10]. However, acute hepatitis C still exists by needle-stick injury in health care workers[1]. Interferon therapy has been indicated for acute hepatitis C for many years but the strategies were controversial in the points of optimal timing of starting therapy, treatment regimen, duration of interferon injection, and management of self-limited patients. Therefore the standard therapy for acute hepatitis C has not been established.

Treatment regimen varies with the times and institutes. Interferon-beta was indicated in the early 1990’s[11]. Interferon-alpha based therapies have been widely indicated, doses were 3-6 million units, durations were 24-52 wk, and recently, combination with ribavirin and pegylated-interferon were reported[12].

Jaeckel et al reported that they treated acute hepatitis C with interferon-alpha (5 million units, thrice weekly for 20 wk) and obtained virological response in 98% of cases, thus, they suggested early treatment immediately on diagnosis[5]. On the other hand, self-limited hepatitis was reported in 15%-30% of acute hepatitis C[7]. identifying the patients who recover spontaneously is important because interferon therapy involves considerable adverse effects, compromises patients’ quality of life for long-term treatment, and is highly expensive. Predictable factors of self-limited acute hepatitis C were reported. Female gender[6], younger age[13], and the lack of complications such as human immunodeficiency virus infection[14] were reported as host factors. HCV genotype 3 and 2 were reported as virological factors[15]. Clinical features during the acute phase of infection as symptomatic disease[6] and fast and continuous decline in viral load were reported with a lower rate of chronicity[7]. Hofer et al reported that mean duration of spontaneous recovery from acute HCV infection was 77 d from infection and 35 d from the onset of symptoms[7]. Gerlach et al reported that they treated acute hepatitis C patients who could not obtain spontaneous viral clearance within 12 wk by interferon-alpha based therapy (3-5 million units, thrice weekly for 14-61 wk) and that the overall virological response was 91% of cases[6]. A meta-analysis indicated that delaying therapy by 60 d after the onset of symptoms did not reduce the efficacy of treatment[16]. Wedemeyer et al defined the course of acute hepatitis C virus infection as five phases which were: phase A, post-exposure; phase B, asymptomatic viremic patients with normal ALT, two to six weeks post-exposure before the onset of symptoms; phase C, acute hepatitis with ALT elevation and symptoms; phase D, spontaneous recovery or partial tolerization; phase E, chronic hepatitis after more than six months of infection[17]. Nomura et al reported that the SVR to 24 wk of interferon-alpha was 100% when therapy was initiated in acute hepatitis phase, but fell to 53% if treatment was applied in chronic phase[8], though it seems a much high rate to be compared with the SVR rate of conventional interferon monotherapy in chronic hepatitis C.

In our case, we initially expected spontaneous recovery because the patient was of female gender, younger age, because she developed symptoms of jaundice and ascites, and because a fast and continuous decline in viral load was observed. However, HCV RNA level remained at 1.0 kIU/L on year after the onset of the infection. Also liver biopsy indicated the progress to chronic hepatitis. The patient desired to complete the treatment in a short period of time because she has recently completed delivery and she wanted to spend the time with her child and to breastfeed the child, thus we treated her with interferon-beta for eight weeks and obtained the SVR.

Interferon-beta therapy is a useful treatments for acute hepatitis C in chronic phase and is superior to interferon-alpha based therapy with regard to treatment duration. Further studies are necessary to clarify the efficacy of this therapy for acute hepatitis C.

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Mihm S E- Editor Bai SH

| 1. | Kiyosawa K, Sodeyama T, Tanaka E, Nakano Y, Furuta S, Nishioka K, Purcell RH, Alter HJ. Hepatitis C in hospital employees with needlestick injuries. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:367-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kiyosawa K, Sodeyama T, Tanaka E, Gibo Y, Yoshizawa K, Nakano Y, Furuta S, Akahane Y, Nishioka K, Purcell RH. Interrelationship of blood transfusion, non-A, non-B hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis by detection of antibody to hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 1990;12:671-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 927] [Cited by in RCA: 881] [Article Influence: 25.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Giuberti T, Marin MG, Ferrari C, Marchelli S, Schianchi C, Degli Antoni AM, Pizzocolo G, Fiaccadori F. Hepatitis C virus viremia following clinical resolution of acute hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 1994;20:666-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Vogel W, Graziadei I, Umlauft F, Datz C, Hackl F, Allinger S, Grünewald K, Patsch J. High-dose interferon-alpha2b treatment prevents chronicity in acute hepatitis C: a pilot study. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:81S-85S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Jaeckel E, Cornberg M, Wedemeyer H, Santantonio T, Mayer J, Zankel M, Pastore G, Dietrich M, Trautwein C, Manns MP. Treatment of acute hepatitis C with interferon alfa-2b. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1452-1457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 552] [Cited by in RCA: 497] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gerlach JT, Diepolder HM, Zachoval R, Gruener NH, Jung MC, Ulsenheimer A, Schraut WW, Schirren CA, Waechtler M, Backmund M. Acute hepatitis C: high rate of both spontaneous and treatment-induced viral clearance. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:80-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 357] [Cited by in RCA: 350] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hofer H, Watkins-Riedel T, Janata O, Penner E, Holzmann H, Steindl-Munda P, Gangl A, Ferenci P. Spontaneous viral clearance in patients with acute hepatitis C can be predicted by repeated measurements of serum viral load. Hepatology. 2003;37:60-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nomura H, Sou S, Tanimoto H, Nagahama T, Kimura Y, Hayashi J, Ishibashi H, Kashiwagi S. Short-term interferon-alfa therapy for acute hepatitis C: a randomized controlled trial. Hepatology. 2004;39:1213-1219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kiyosawa K, Umemura T, Ichijo T, Matsumoto A, Yoshizawa K, Gad A, Tanaka E. Hepatocellular carcinoma: recent trends in Japan. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S17-S26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Alter HJ, Houghton M. Clinical Medical Research Award. Hepatitis C virus and eliminating post-transfusion hepatitis. Nat Med. 2000;6:1082-1086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Omata M, Yokosuka O, Takano S, Kato N, Hosoda K, Imazeki F, Tada M, Ito Y, Ohto M. Resolution of acute hepatitis C after therapy with natural beta interferon. Lancet. 1991;338:914-915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zekry A, Patel K, McHutchison JG. Treatment of acute hepatitis C infection: more pieces of the puzzle. J Hepatol. 2005;42:293-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kenny-Walsh E. Clinical outcomes after hepatitis C infection from contaminated anti-D immune globulin. Irish Hepatology Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1228-1233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 658] [Cited by in RCA: 650] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Thomas DL, Astemborski J, Rai RM, Anania FA, Schaeffer M, Galai N, Nolt K, Nelson KE, Strathdee SA, Johnson L. The natural history of hepatitis C virus infection: host, viral, and environmental factors. JAMA. 2000;284:450-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 758] [Cited by in RCA: 778] [Article Influence: 31.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Larghi A, Zuin M, Crosignani A, Ribero ML, Pipia C, Battezzati PM, Binelli G, Donato F, Zanetti AR, Podda M. Outcome of an outbreak of acute hepatitis C among healthy volunteers participating in pharmacokinetics studies. Hepatology. 2002;36:993-1000. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Licata A, Di Bona D, Schepis F, Shahied L, Craxí A, Cammà C. When and how to treat acute hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2003;39:1056-1062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wedemeyer H, Jäckel E, Wiegand J, Cornberg M, Manns MP. Whom When How Another piece of evidence for early treatment of acute hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2004;39:1201-1203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |