Published online Jul 28, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i28.4565

Revised: March 12, 2006

Accepted: February 28, 2006

Published online: July 28, 2006

AIM: To evaluate the prognostic value of some pathological variables in rectal cancer survival.

METHODS: 247 patients who underwent curative resection of rectal cancer were included in the study. The influence on survival of five pathological variables (histopathological tumor type, histopathological tumor grade differentiation, blood vessel invasion, perineural invasion and lymphatic invasion) was assessed using statistical analyses.

RESULTS: Overall 5-year survival was 71.2%. Univariate analysis of all tested variables showed an effect on survival but only the effect of lymphatic invasion was statistically significant. At stages three and four it had a negative effect on survival (P = 0.0212). Lymphatic invasion also significantly affected cancer related survival in multivariate analysis at stages three and four. At lower stages (stage 0, stage 1 and stage 2) multivariate analysis showed a negative effect of perineural invasion on cancer related survival.

CONCLUSION: Patients with lymphatic and perineural invasion have a higher risk for rectal cancer related death after curative resection. Examination of these variables should be an important step in detecting patients with a poorer prognosis.

- Citation: Krebs B, Kozelj M, Kavalar R, Gajzer B, Gadzijev EM. Prognostic value of additional pathological variables for long-term survival after curative resection of rectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(28): 4565-4568

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i28/4565.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i28.4565

Rectal cancer is often a curable disease and survival is directly correlated with the stage of the tumor, assessed by indicating the depth of penetration of the tumor into the bowel wall (T stage), the extent of lymph node involvement (N stage), and the presence of distant metastases (M stage). Besides the degree of penetration and presence of nodal involvement or distant metastasis, many other clinical, histological and biomolecular variables have been evaluated in the prognosis of patients with rectal cancer, although most have not been prospectively validated[1-3]. Among those, pathological factors are especially important as they may help to sub stratify tumors of same stage into different risk categories[4].

In Slovenia as in most countries, patients with radically resected rectal cancer with negative lymph nodes do not receive adjuvant systemic therapy, since significant survival benefits have not yet been proven[5]. One third of those patients, however, will develop local or distant metastases[6]. Identifying such patients would be very important because they could benefit from adjuvant systemic treatment.

The aim of our study was to retrospectively examine five histopathological prognostic factors which are routinely assessed and which may help to identify patients who could be included in an adjuvant chemotherapy program.

The majority of colorectal cancers are adenocarcinomas. Some subtypes, like mucinous carcinoma (defined in the recent TNM classification as tumors with mucinous areas comprising more than 50% of tumor), signet ring cell carcinoma, and undifferentiated carcinoma, have a worse prognosis than adenocarcinoma.

In some multivariate studies, the microscopic grade is predictive of survival; a higher grade is known to be associated with a significantly increased risk of an adverse outcome.

Blood vessel (venous) invasion by tumor has been demonstrated to be a stage-independent adverse prognostic factor by many analyses[7-9]. However, some studies identifying venous invasion as an adverse factor on univariate analysis have failed to confirm its independent impact on prognosis in multivariate breakdowns[12].

Similar disparate results have also been reported for lymphatic invasion[10-11]. Therefore, data from existing studies are difficult to interpret. Nevertheless, the importance of venous and lymphatic invasion by the tumor is strongly suggested and largely confirmed by the literature[4].

PNI may influence prognosis after resection of rectal cancer. An abundant extramural autonomic nerve network is an anatomical feature of the rectum. The evidence for the importance of perineural invasion is weaker than for blood vessel or lymphatic invasion but it has been shown in some series to be a predictor of both local failure and worse survival[13-15].

Since 1998, data from all rectal cancer patients in our institution have been simultaneously registered in specially designed protocols, which contain preoperative, operative and postoperative parts and detailed pathological report.

The stage of the rectal cancer was defined according to the recent TNM classification[16].

Blood vessel invasion was considered positive if the following criteria were fulfilled: tumor cells at endothelial surface, tumor cell thrombi inside the lumen of the vessel or destruction of the vascular wall by tumor. Lymphatic invasion was defined as positive when tumor cells were found within endothelium-lined space devoid of mural smooth muscle or elastic fibers. Perineural invasion was considered positive when tumor cells were detected along, or around, a nerve within the perineural space.

Data from all patients who were operated on between January 1998 and December 2003 were analyzed. Over this period 512 patients with rectal carcinoma underwent surgery, but only 247 patients were eligible for the study, which included patients with elective radical resection of a solitary rectal tumor who survived the first month after the operation.

All patients were followed up on regular basis: at 3 mo intervals during the first 2 years, at 6 mo intervals until 5th year and then yearly. Clinical examination, tumor markers (CEA and CA19-9) and ultrasound were performed at each appointment. Chest X-ray was performed every 6 mo during first 2 years and then yearly. Colonoscopy was performed yearly after the operation. Follow up was updated on March 1st 2005.

We analyzed the following pathological variables: Histopathological tumor type, tumor grade or differentiation (well, moderately well, poorly differentiated and undifferentiated), blood vessel invasion, lymphatic and perineural invasion (present or absent).

Mortality data was acquired from the Slovenian cancer register and cause was verified for each deceased patient.

The research received approval from our ethics committee.

Survival was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by log-rank test. Multivariate analysis was performed using Cox’s regression model. All analyses were performed using statistical software SPSS for Windows 10.0.

The main operative procedures for rectal cancer in our institution are radical low anterior resection and abdominoperineal resection. Both procedures are executed according to principles of total mesorectal excision.

All patients were postoperatively managed by oncologists. The majority of patients with stage 3 and 4 disease received postoperative chemotherapy if there were no general contraindications.

The mean follow up time was 1055 days. The basic demographic analysis is shown in Table 1.

| Age (yr) | 65.8 (range 34-90)n (%) |

| Sex | |

| Men | 138 (56) |

| Women | 109 (44) |

| Follow up (d) | Median 1055 (range 31-2591) |

Most of the patients had stage 2 disease (47%), 29% had stage 3 and 22% stage 1. Only one percent of patients were at stage 0 and stage 4, as shown in Table 2.

| UICC | n = 247 | % |

| 0 | 2 | 1 |

| 1 | 54 | 22 |

| 2 | 116 | 47 |

| 3 | 72 | 29 |

| 4 | 3 | 1 |

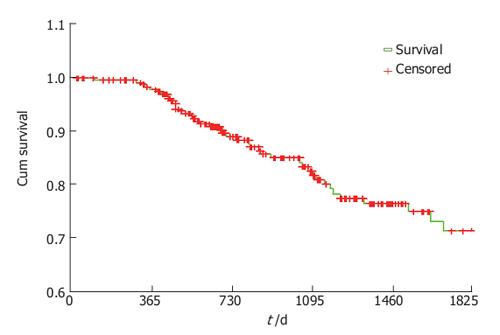

5-year cancer related survival was calculated using Kaplan-Meyer method and was 71.4% for all stages.

For stage 1, survival was 91%, for stage 2.74%, for stage 3.51% and for stage 4. 33% (Figure 1).

For further analysis patients were divided into two groups according to stage. One group consisted of patients with stage zero, one and two tumors, and the second group consisted of patients with tumor stage three and four (Table 3).

| Variable | All Cases | LOWER STAGES (Stages 0, 1 and 2) | HIGHER STAGES (Stages 3 and 4) | |||

| 5-yr cancer related survival (%) | P (log-rank test) | 5-yr cancer related survival (%) | P (log-rank test) | |||

| n | % | |||||

| Histological type | n = 246 | |||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 214 | 87 | 79 | 0.4056 | 42 | 0.5016 |

| Mucinous carcinoma | 23 | 9 | 83 | 74 | ||

| Other types | 9 | 4 | / | 66 | ||

| Differentiation | n = 235 | |||||

| G1 | 70 | 30 | 77 | 0.1312 | 43 | 0.5792 |

| G2 | 141 | 60 | 87 | 63 | ||

| G3 | 21 | 8.9 | 51 | 42 | ||

| G4 | 3 | 0.1 | / | / | ||

| Blood vessel invasion | n = 226 | |||||

| Positive | 28 | 12 | 71 | 0.5920 | 46 | 0.2009 |

| Negative | 195 | 88 | 77 | 54 | ||

| Perineural invasion | n = 224 | |||||

| Positive | 31 | 14 | 74 | 0.1143 | 31 | 0.4247 |

| Negative | 193 | 86 | 78 | 53 | ||

| Lymphatic invasion | n = 218 | |||||

| Positive | 30 | 14 | 85 | 0.9083 | 27 | 0.0212 |

| Negative | 188 | 86 | 76 | 68 | ||

The histopathological type of tumor and the degree of differentiation affected survival in lower and higher stages but this difference was not statistically significant.

Vascular and perineural invasion also showed no effect on 5-year survival in lower and higher stages.

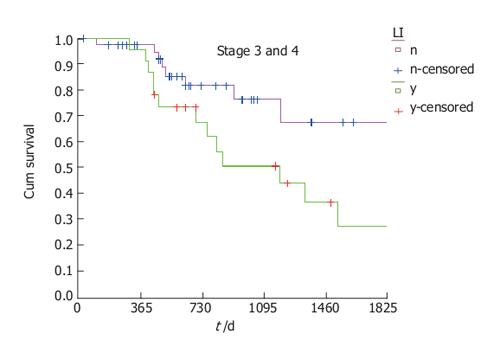

Lymphatic invasion showed no effect on survival in lower stages but in higher stages, positive lymphatic invasion had a statistically significant negative effect on survival (log rank, P = 0.0212) (Figure 2).

Using Cox regression model on all previous variables we obtained different results for the different stages. Examining patients with higher stages we again confirmed that lymphatic invasion is an important prognostic variable. In multivariate analysis, lymphatic invasion clearly emerged as a strong negative prognostic factor (P = 0.022).

On the other hand, when patients with lover stages were considered, another variable, perineural invasion, seemed to have the greatest effect on survival (P = 0.036).

Rectal cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths in the developed world[17].

Slovenia has one of the highest incidences of rectal cancer (men: 23.7 per 100 000, women 14.9 per 100 000). In 2001 there were 383 new cases of rectal cancer detected and 128 cancer-related deaths[18].

We know that more than two-thirds of patients with newly detected rectal cancer will undergo curative primary tumor resection and more than half will eventually die from the disease following surgery[19]. Survival is clearly dependent on rectal cancer stage but there are many other variables that could help us in predicting outcome. During recent years there were many studies and methods which focused on identification of factors that could influence postoperative survival after curative rectal cancer resection.These include serial sectioning, immunohistochemistry, and polymerase chain reaction assays. Examining all regional lymph nodes with these methods would be preferred, but is expensive and time consuming and therefore not feasible in daily practice.

Sentinel node-mapping offers a potential solution. It has been introduced in colorectal cancer to improve staging by facilitating occult tumor cell assessment in lymph nodes that are most likely to be tumor-positive[20]. However, there is a large variation in identification rates and false-negative rates usually ascribed to the learning curve effect, differences in technique and tumor stage.

Compared to the methods described above, pathological variables, as assessed in this work, may have some advantages. They are not expensive and do not need any special resources.

In our study, lymphatic and perineural invasion were pathological variables that were significantly associated with pooreroutcomes in high and low stage groups, respectively. The importance of lymphatic invasion was already recognized in the late 1980’s. Minsky found that it was an independent prognostic factor by proportional hazard analysis[21]. The importance of lymphatic invasion was confirmed in some later studies but also denied in others[22]. In our work it had a clearly negative effect on survival in a univariate analysis. In a multivariate analysis, the negative effect was seen only in patients with node positive rectal cancer. We assume that positive lymph nodes facilitate lymphatic invasion that could precipitate further spreading of the disease.

According to available data, perineural invasion may influence the prognosis after resection of rectal cancer[13]. In our work perineural invasion was associated with shorter survival in patients with lower stages of tumors. It is possible that the influence of positive perineural invasion in higher stages is masked by the importance of other parameters, and thus its role is clearly seen only in lower stages.

We must, however, mention some limitations of our study. First, although we report a 5-year overall survival, our median follow-up was 1055 d. However, we have used the Kaplan-Meier method to estimate 5-year survival. Second, we performed a retrospective study, and therefore our conclusions are limited by the bias inherent in an analysis of this nature.

In conclusion, additional pathological variables deservemore research to validate whether they will be helpful in predicting outcomes in rectal cancer patients. They are not expensive, are performed routinely and do not need any special resources. They could help with the identification of patients who would be predicted to have a poorer prognosis after curative resection of rectal cancer, who accordingly might benefit from adjuvant oncological treatment.

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Barrett KE E- Editor Bi L

| 1. | Jen J, Kim H, Piantadosi S, Liu ZF, Levitt RC, Sistonen P, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Hamilton SR. Allelic loss of chromosome 18q and prognosis in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:213-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 524] [Cited by in RCA: 493] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lanza G, Matteuzzi M, Gafa R, Orvieto E, Maestri I, Santini A, del Senno L. Chromosome 18q allelic loss and prognosis in stage II and III colon cancer. Int J Cancer. 1998;79:390-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Compton CC, Greene FL. The staging of colorectal cancer: 2004 and beyond. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:295-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 302] [Cited by in RCA: 311] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chapuis PH, Dent OF, Fisher R, Newland RC, Pheils MT, Smyth E, Colquhoun K. A multivariate analysis of clinical and pathological variables in prognosis after resection of large bowel cancer. Br J Surg. 1985;72:698-702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 331] [Cited by in RCA: 328] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Moertel CG, Fleming TR, Macdonald JS, Haller DG, Laurie JA, Goodman PJ, Ungerleider JS, Emerson WA, Tormey DC, Glick JH. Levamisole and fluorouracil for adjuvant therapy of resected colon carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:352-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1678] [Cited by in RCA: 1625] [Article Influence: 46.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wolmark N, Fisher B, Wieand HS. The prognostic value of the modifications of the Dukes' C class of colorectal cancer. An analysis of the NSABP clinical trials. Ann Surg. 1986;203:115-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Newland RC, Dent OF, Lyttle MN, Chapuis PH, Bokey EL. Pathologic determinants of survival associated with colorectal cancer with lymph node metastases. A multivariate analysis of 579 patients. Cancer. 1994;73:2076-2082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Harrison JC, Dean PJ, el-Zeky F, Vander Zwaag R. From Dukes through Jass: pathological prognostic indicators in rectal cancer. Hum Pathol. 1994;25:498-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Talbot IC, Ritchie S, Leighton MH, Hughes AO, Bussey HJ, Morson BC. The clinical significance of invasion of veins by rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 1980;67:439-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 286] [Cited by in RCA: 285] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Takebayashi Y, Aklyama S, Yamada K, Akiba S, Aikou T. Angiogenesis as an unfavorable prognostic factor in human colorectal carcinoma. Cancer. 1996;78:226-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hermanek P, Guggenmoos-Holzmann I, Gall FP. Prognostic factors in rectal carcinoma. A contribution to the further development of tumor classification. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:593-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Takahashi Y, Tucker SL, Kitadai Y, Koura AN, Bucana CD, Cleary KR, Ellis LM. Vessel counts and expression of vascular endothelial growth factor as prognostic factors in node-negative colon cancer. Arch Surg. 1997;132:541-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ueno H, Hase K, Mochizuki H. Criteria for extramural perineural invasion as a prognostic factor in rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2001;88:994-1000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shirouzu K, Isomoto H, Kakegawa T. Prognostic evaluation of perineural invasion in rectal cancer. Am J Surg. 1993;165:233-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Feil W, Wunderlich M, Kovats E, Neuhold N, Schemper M, Wenzl E, Schiessel R. Rectal cancer: factors influencing the development of local recurrence after radical anterior resection. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1988;3:195-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sobin LH, Wittekind Ch. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. 6th ed. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons 2002; . |

| 17. | Landis SH, Murray T, Bolden S, Wingo PA. Cancer statistics, 1999. CA Cancer J Clin. 1999;49:8-31, 1. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Tyczynski JE, Plesko I, Aareleid T, Primic-Zakelj M, Dalmas M, Kurtinaitis J, Stengrevics A, Parkin DM. Breast cancer mortality patterns and time trends in 10 new EU member states: mortality declining in young women, but still increasing in the elderly. Int J Cancer. 2004;112:1056-1064. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Wichmann MW, Müller C, Hornung HM, Lau-Werner U, Schildberg FW. Gender differences in long-term survival of patients with colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1092-1098. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Doekhie FS, Peeters KC, Kuppen PJ, Mesker WE, Tanke HJ, Morreau H, van de Velde CJ, Tollenaar RA. The feasibility and reliability of sentinel node mapping in colorectal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2005;31:854-862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Minsky BD, Mies C, Rich TA, Recht A. Lymphatic vessel invasion is an independent prognostic factor for survival in colorectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;17:311-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Takahashi T, Kato T, Kodaira S, Koyama Y, Sakabe T, Tominaga T, Hamano K, Yasutomi M, Ogawa N. Prognostic factors of colorectal cancer. Results of multivariate analysis of curative resection cases with or without adjuvant chemotherapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 1996;19:408-415. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |