Published online Mar 7, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i9.1399

Revised: December 12, 2003

Accepted: January 30, 2004

Published online: March 7, 2005

AIM: Metastases from lung cancer to gastrointestinal tract are not rare at postmortem studies but the development of clinically significant symptoms from the gastrointestinal metastases is very unusual.

METHODS: Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues were cut into 5 μm thick sections and routinely stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Some slides were also stained with Alcian-PAS. Antibodies used were primary antibodies to pancytokeratin, cytokeratin 7, cytokeratin 20, epithelial membrane antigen, vimentin, smooth muscle actin and CD-117.

RESULTS: We observed three patients who presented with multiple metastases from large cell bronchial carcinoma to small intestine. Two of them had abdominal symptoms (sudden onset of abdominal pain, constipation and vomiting) and in one case the tumor was incidentally found during autopsy. Microscopically, all tumors showed a same histological pattern and consisted almost exclusively of strands and sheets of poorly cohesive, polymorphic giant cells with scanty, delicate stromas. Few smaller polygonal anaplastic cells dispersed between polymorphic giant cells, were also observed. Immunohistochemistry showed positive staining of the tumor cells with cytokeratin and vimentin. Microscopically and immunohistochemically all metastases had a similar pattern to primary anaplastic carcinoma of the small intestine.

CONCLUSION: In patients with small intestine tumors showing anaplastic features, especially with multiple tumors, metastases from large cell bronchial carcinoma should be first excluded, because it seems that they are more common than expected.

- Citation: Tomas D, Ledinsky M, Belicza M, Krušlin B. Multiple metastases to the small bowel from large cell bronchial carcinomas. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(9): 1399-1402

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i9/1399.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i9.1399

Metastases from lung cancer to gastrointestinal tract are not rare at postmortem studies but the development of clinically significant symptoms from the gastrointestinal metastases is very unusual. Small bowel metastases from lung carcinoma are also not uncommon and may be seen more frequently as patients live longer after their diagnosis of cancer. Small bowel metastases must be considered in any patient with both lung carcinoma and abdominal pain, and should be expected in patients with both lung carcinoma and acute abdomen. The major manifestations are gastrointestinal hemorrhage (occult or massive), ileus, intussusceptions, and perforation[1-7]. On the other hand, primary malignant tumors of the small intestine are rare, especially anaplastic carcinoma. Very few of these malignant neoplasms have been reported in the literature. The major manifestations are the same as in metastatic tumors[8-15]. We described three patients with large cell bronchial carcinoma having multiple metastases to small intestine. Diagnosis of primary large cell bronchial carcinoma was confirmed by cytological or pathohistological examination in all patients.

A 64-year-old man who was previously diagnosed having large cell bronchial carcinoma by cytology presented with sudden onset of abdominal pain, constipation and vomiting. Two years earlier the patient was treated with four cycles of chemotherapy and TCT. Disturbances persisted for two days before admission. Physical examination revealed diffuse pain on deep abdominal palpation and weakness of intestinal passage. Blood examination showed leukocytosis, anemia and slightly elevated glucose. Lung radiography was done and showed no signs of bronchial carcinoma or mediastinal lymph node enlargement. The patient was treated with a nasogastrical probe, infusion of physiological solution and intravenous metoklopramid and trospij application. Abdominal ultrasonography showed subileus of small intestine. After ultrasonography the patient underwent abdominal computed tomography scan that confirmed subileus and revealed few solid tumors in jejunum. Liver, spleen, gallbladder, pancreas and abdominal lymph nodes had no signs of tumor infiltration. Five days after admission, surgical resection of 30 cm of small intestine with adjacent mesenterium and regional lymph nodes was performed. During surgery, three intraluminal cherry-like tumors and four knots in mesenterial fat were palpable. The knots were gummy. No other signs of tumor expansion were found. The patient had no complication during the postoperative course and was discharged ten days after surgery with suggested oncological examination and treatment. No additional therapy was performed as suggested by oncologists. One year after surgery the patient was still alive and showed no signs of tumor spread.

A 63-year-old woman who had large cell bronchial carcinoma confirmed by small biopsy with metastases in suprarenal glands, liver and brain. Diagnosis was made eight months ago and the patient underwent chemotherapy and TCT. The patient presented with sudden onset of abdominal pain and vomiting. Disturbances started one day before admission. The physical examination revealed hardness of abdominal wall and diffuse pain on abdominal palpation. Intestinal passage was weak. Blood examination showed leukocytosis and anemia. Abdominal radiography and ultrasonography showed perforations of small intestine with free air in peritoneum. The patient underwent urgent surgery and 27 cm of small intestine with adjacent mesenterium was resected. During surgery, two tumors which penetrated the wall of small intestine, were seen. The patient had no complication during the postoperative course and was discharged nine days after surgery with suggested continuation of oncological treatment. Two months after surgery the patient died at home. Autopsy was not performed.

A 60-year-old woman presented with sudden onset of psychical disorientation and back pain extending to the left leg. Head computed tomography scan excluded brain damage, but lung radiography revealed tumorous infiltration in the right upper lung lobe. The patient was hospitalized and additional examinations showed increased body temperature, leukocytosis, anemia, slight hypoxemia and sinus tachycardia. Bone radiography showed no sign of metastases. The patient was treated with analgetics, sedatives, antibiotics, antiarrhythmic drugs and infusion of physiological solution. Two days after admission, the patient became unconscious and died. Autopsy revealed nonhemorrhagic brain infarct located in parietal right region as a cause of death. Pathological examination confirmed large (eight centimeter in diameter) neoplastic process in right upper bronchus and found metastasis in left adrenal gland. During the resection of small intestine, a pathologist revealed four whitish tumors in the wall. Tumors measured between 1 and 2 centimeters in diameter and intestinal wall between tumors had no sign of tumor involvement. On the cut surface, tumors were partially necrotic, soft and did not penetrate intestinal wall.

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues were cut into 5 μm thick sections and routinely stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Some slides were also stained with Alcian-PAS. Deparaffinization and immunohistochemical staining were performed following microwave streptavidin immunoperoxidase (MSIP) protocol on a DAKO TechMateTM Horizon automated immunostainer. We used primary antibodies to pancytokeratin, cytokeratin 7, cytokeratin 20, epithelial membrane antigen, vimentin, smooth muscle actin and CD-117 (purchased from DAKO, Copenhagen, Denmark). Dilution of all antibodies was “ready to use”.

Pathologic examination revealed three separate polypoid tumors in intestinal lumen, the distance between tumors was at least 3 cm (Figure 1). Intestinal wall between tumors had no sign of tumor spread or infiltration. The tumors had a maximum diameter between 1.5 and 4 cm and showed an expansive growth. In the adjacent mesenteric fat tissue four knots were found. One knot was measured 8 cm and the other three were up to 1 cm. On the cut surface, tumors and knots were whitish, flashy and soft.

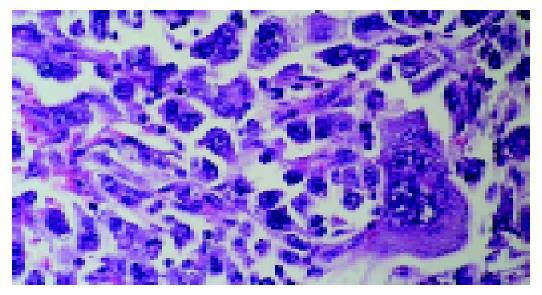

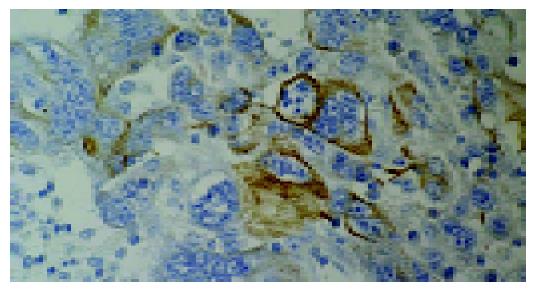

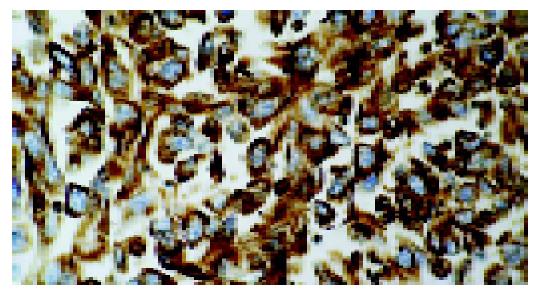

Microscopically all tumors showed a same histological pattern and consisted almost exclusively of strands and sheets of poorly cohesive, polymorphic giant cells with scanty, delicate stromas (Figure 2). Few smaller polygonal anaplastic cells dispersed between polymorphic giant cells, were also observed. Tumor giant cells were anaplastic with abundant light eosinophilic cytoplasms. The nuclei were pleomorphic with distinct nuclear membranes, irregular chromatin clumping and pushed to the edge of cells. Each nucleus contained one or more prominent nucleoli. Smaller polygonal cells had same nuclei and the only difference between two cell types was the cytoplasm size and shape. Mitotic index was high with typical and atypical mitotic figures. Mucosal ulceration, focal necrosis and hemorrhage were found. Diffuse and slight infiltration with mononuclear and polymorph cells was also seen in all tumors and metastases. Tumors infiltrated submucosa but muscular part of intestinal wall was not affected. Two mesenterial knots were built of the same tumorous tissue and the other two were built of lymph nodes without signs of tumor infiltration. The surgical margins were free of tumor. Special stain (Alcian-PAS) demonstrated no intracellular or extracellular mucin. Immunohistochemically, tumor cells at both sites, intestinal and lymph nodes, were focally positive for pancytokeratin (Figure 3), cytokeratin 7, cytokeratin 20 and epithelial membrane antigen and diffusingly positive for vimentin (Figure 4). Smooth muscle actin and CD-117 were negative.

The diagnosis of primary anaplastic carcinoma of small bowel was suggested. However, careful clinical check-up was recommended in order to exclude primary giant cell bronchial cancer. Few weeks after diagnosis was established, we got some additional information about the patient. Two years earlier, the patient was treated for pulmonary carcinoma with four cycles of chemotherapy and TCT (cytological diagnosis was large cell pulmonary carcinoma). Lung radiography was done before surgical resection of small intestine and showed no signs of bronchial carcinoma or mediastinal lymph node enlargement. These data suggested the diagnosis of metastatic large cell bronchial carcinoma.

Pathologic examination revealed two separate whitish tumors in intestinal wall, the distance between tumors was 22 cm. Intestinal wall between tumors had no sign of tumor involvement. The tumors had a maximum diameter 1.5 and 2.5 cm and were partially necrotic, flashy and soft on the cut surface with obvious affection of intestinal serosa. Microscopically both tumors showed a same histological pattern as described previously. Tumors penetrated intestinal serosa and spread to adjacent fat tissues. No tumor was found at the surgical margins. Imunohistochemically tumor cells were focally positive for pancytokeratin and diffusely positive for vimentin. We compared these microscopic findings with findings in first patient and asked additional data about the patient. Additional data showed the existence of an extended large cell bronchial carcinoma and diagnosis of metastatic large bronchial carcinoma was made.

Microscopically all four tumors (lung, adrenal glands and four intestinal tumors) showed a same histological pattern that was previously described and were similar to those found in large cell bronchial carcinoma.

Primary malignant tumors of the small intestine are rare and easy to be misdiagnosed because of their low morbidity and nonspecific clinical manifestations[15]. Metastases in small intestine are also rare, especially multiple ones. Primary and metastatic tumors share the same clinical manifestations and diagnostic problems[1-3,5,15]. All our patients had multiple metastases and all tumors were predominantly composed of large anaplastic cells, which expressed both epithelial and mesenchymal immunohistochemical markers. In the first case we were not completely sure that the tumor was metastatic because polypoid growth pattern, multiple tumors and affection of mesenterial lymph nodes were not characteristic for metastatic tumors. Incomplete clinical data and lung radiography that was done before surgery failed to confirm the metastasis of lung cancer. The next two cases showing similar features more commonly favor metastatic tumors from primary lung cancer. Lung cancer is most commonly metastatic to mediastinal lymph nodes, pleura, liver, bone, brain and adrenals, but some authors proved that symptomatic small bowel metastases could occur early in the course of the disease[2,7]. Previous reports of such metastases of the small bowel have documented a very poor prognosis for such patients[1-7]. Diagnostic problems might appear due to the lack of appropriate clinical data or when primary tumor was unknown because clinical symptoms, microscopic pattern and immunohistochemical profile of large cell bronchial carcinoma metastases were similar to primary anaplastic carcinoma of the small intestine. Predominant sites of anaplastic carcinoma (so called pleomorphic carcinoma, sarcomatoid carcinoma, giant cell carcinoma or carcinosarcoma) are lung, pancreas, thyroid and gallbladder. It is very uncommon in small intestine. According to the predominance of cell type, these tumors could be subdivided in three types: giant (gemistocytic) cell type, spindle cell type or mixed type[8-14]. Bak et al[9] reported four cases of giant cell carcinoma, two in small intestine (tumors were multiple) and two in large bowel (in one case tumor was multiple), and concluded on the basis of the same light and electron microscopy, nuclear characteristics and identical immunohistochemical reaction that the distinction among three cell types was the shape and amount of cytoplasm and believed that gemistocytic cells evolved from smaller polygonal cells. Gemistocytic cells were identical to the giant cells of pulmonary giant cell carcinoma. The size of gemistocytic cells varied and larger cells had two or more nuclei. All the three cell types were imunohistochemically positive for epithelial (cytokeratin, epithelial membrane antigen) and mesenchymal markers (vimentin). Some of these tumors were also positive for neuroendocrine markers (neuron specific enolase, chromogranin)[8,9,11,12]. The WHO classification of lung cancer recognizes spindle cell carcinoma and giant cell carcinoma as separate neoplasms related to squamous cell carcinomas and large cell carcinomas, but some authors included these group tumors with adenocarcinomatous foci and considered all giant cell carcinomas to be poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas[9]. Indeed the foci of squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma were found in 10% and 45% of pleomorphic carcinomas, respectively, and produced an additional uncertainty as to the distinctive nature of this tumor type[16]. In adenocarcinomas of the lungs, pancreas and thyroid, focal giant cell formation was sometimes seen but these cells retained some characteristics of their origin and had no typical gemistocytic morphology[9]. Przygodzki et al[16]. tested the hypothesis that pleomorphic carcinomas (giant and spindle cell) were one entity separated from squamocellular carcinomas or adenocarcinomas by evaluating the mutational spectrum seen in these tumor types. They compared the mutation type and the rate of K-ras-2 and p53 genes in pleomorphic and squamocellular adenocarcinoma and revealed significant differences in the pattern and frequency of genetic mutations between all three types of tumors and according to these findings separate histopathologic classification of these tumors were recommended. Before these findings, Agrawal et al[8] also proved that pleomorphic carcinomas had no connections with squamocellular adenocarcinomas and thought that some of the histological, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural differentiation characteristics were similar with carcinoid tumors and considered that these tumors were poorly differentiated variants of neuroendocrine carcinomas. Despite the name and origin, anaplastic carcinoma is a rare variant of small intestinal carcinoma with an aggressive clinical course and poor outcome and must be distinguished from large cell bronchial carcinoma metastases, which may be the first sign of lung malignancy[11-15]. In conclusion, multiple metastatic intestinal tumors from primary large cell bronchial carcinoma are more common than generally believed. Therefore in patients with small intestine tumors with anaplastic features, especially in patients with multiple tumors, metastases from large cell bronchial carcinoma must be excluded because they might be more common than expected.

Assistant Editor Li WZ Edited by Wang XL, Xu CT and Xu FM

| 1. | Akahoshi K, Chijiiwa Y, Hirota I, Ohogushi O, Motomatsu T, Nawata H, Sasaki I. Metastatic large-cell lung carcinoma presenting as gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 1996;59:217-219. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Berger A, Cellier C, Daniel C, Kron C, Riquet M, Barbier JP, Cugnenc PH, Landi B. Small bowel metastases from primary carcinoma of the lung: clinical findings and outcome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1884-1887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dalton ML, Simon KB, Gatling RR, Koury AM. Large cell carcinoma of the lung with isolated jejunal metastasis. J Miss State Med Assoc. 1989;30:361-363. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Hinoshita E, Nakahashi H, Wakasugi K, Kaneko S, Hamatake M, Sugimachi K. Duodenal metastasis from large cell carcinoma of the lung: report of a case. Surg Today. 1999;29:799-802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mosier DM, Bloch RS, Cunningham PL, Dorman SA. Small bowel metastases from primary lung carcinoma: a rarity waiting to be found? Am Surg. 1992;58:677-682. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Park SW, Cho HJ, Choo WS, Chung KS, Kim HY, Yoo JY, Kim JS, Shin HS. A case of intestinal hemorrhage due to small intestinal metastases from primary lung cancer. Korean J Intern Med. 1991;6:79-84. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Stenbygaard LE, Sørensen JB, Larsen H, Dombernowsky P. Metastatic pattern in non-resectable non-small cell lung cancer. Acta Oncol. 1999;38:993-998. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Agrawal S, Trivedi MH, Lukens FJ, Moon C, Ingram EA, Barthel JS. Anaplastic and sarcomatoid carcinoma of the small intestine: an unusual tumor. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;29:99-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bak M, Teglbjaerg PS. Pleomorphic (giant cell) carcinoma of the intestine. An immunohistochemical and electron microscopic study. Cancer. 1989;64:2557-2564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cavazza A, Sandonà F, Gelli MC, De Marco L, Gardini G. Monophasic sarcomatoid carcinoma of the ileum. Description of a case and review of the literature. Pathologica. 1997;89:425-431. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Fukuda T, Kamishima T, Ohnishi Y, Suzuki T. Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the small intestine: histologic, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural features of three cases and its differential diagnosis. Pathol Int. 1996;46:682-688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jones EA, Flejou JF, Molas G, Potet F. Pleomorphic carcinoma of the small bowel. The limitations of immunohistochemical specificity. Pathol Res Pract. 1991;187:235-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lam KY, Leung CY, Ho JW. Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the small intestine. Aust N Z J Surg. 1996;66:636-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Robey-Cafferty SS, Silva EG, Cleary KR. Anaplastic and sarcomatoid carcinoma of the small intestine: a clinicopathologic study. Hum Pathol. 1989;20:858-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhou ZW, Wan DS, Chen G, Chen YB, Pan ZZ. Primary malignant tumor of the small intestine. World J Gastroenterol. 1999;5:273-276. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Przygodzki RM, Koss MN, Moran CA, Langer JC, Swalsky PA, Fishback N, Bakker A, Finkelstein SD. Pleomorphic (giant and spindle cell) carcinoma is genetically distinct from adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma by K-ras-2 and p53 analysis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1996;106:487-492. [PubMed] |