Published online Sep 14, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i34.5342

Revised: January 1, 2005

Accepted: January 5, 2005

Published online: September 14, 2005

AIM: To evaluate the daily high-dose induction therapy with interferon-α2b (IFN-α2b) in combination with ribavirin for the treatment of patients who failed with interferon monotherapy and had a relapse, based on the assumption that the viral burden would decline faster, thus increasing the likelihood of higher response rates in this difficult-to-treat patient group.

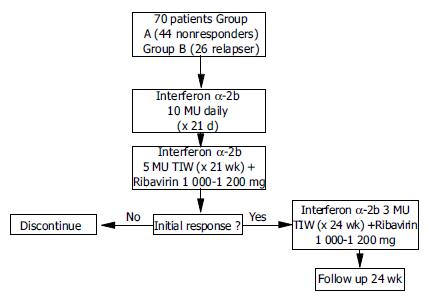

METHODS: Seventy patients were enrolled in this study. Treatment was started with 10 MU IFN-α2b daily for 3 wk, followed by IFN-α2b 5 MU/TIW in combination with ribavirin (1 000-1 200 mg/d) for 21 wk. In case of a negative HCV RNA PCR, treatment was continued until wk 48 (IFN-α2b 3 MU/TIW+1 000-1 200 mg ribavirin/daily).

RESULTS: The dose of IFN-α2b or ribavirin was reduced in 16% of patients because of hematologic side effects, and treatment was discontinued in 7% of patients. An early viral response (EVR) was achieved in 60% of patients. Fifty percent of all patients achieved an end-of-treatment response (EOT) and 40% obtained a sustained viral response (SVR). Patients with no response had a significantly lower response rate than those with a former relapse (SVR 30% vs 53%; P = 0.049). Furthermore, lower response rates were observed in patients infected with genotype 1a/b than in patients with non-1-genotype (SVR 28% vs 74%; P = 0.001). As a significant predictive factor for a sustained response, a rapid initial decline of HCV RNA could be identified. No patient achieving a negative HCV-RNA PCR at wk 18 or later eventually eliminated the virus.

CONCLUSION: Daily high-dose induction therapy with interferon-α2b is well tolerated and effective for the treatment of non-responders and relapsers, when interferon monotherapy fails. A fast decline of viral load during the first 12 wk is strongly associated with a sustained viral response.

- Citation: Hass HG, Kreysel C, Fischinger J, Menzel J, Kaiser S. High-dose interferon-α2b induction therapy in combination with ribavirin for treatment of chronic hepatitis C in patients with non-response or relapse after interferon-α monotherapy. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(34): 5342-5346

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i34/5342.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i34.5342

Chronic infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the main cause of chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma worldwide, more than 2% of the world population are chronically infected with this virus[1,2]. Until introduction of the nucleoside analog ribavirin, standard therapy for chronic hepatitis C was the monotherapy with interferon-α (IFN-α). The initial data published on the efficacy of IFN-α monotherapy demonstrate that about 50% of patients who have achieved a biochemical end-of-treatment response (ETR) have a relapse within the first 6 mo after cessation of treatment[3], only about 6% of patients with genotype 1 and/or high viral load can achieve a sustained viral response (SVR)[4].

Antiviral combination therapy with IFN-α and ribavirin can lead to significant response rates in treatment-of naive patients with chronic hepatitis C; however, sustained response rates for patients with no former response after IFN-α monotherapy are still low (12-16%)[5,6]. Furthermore, recent introduction of pegylated interferons has not resulted in a substantial increase in response rates among non-responders with a SVR rate being 14-27% after IFN-α monotherapy[7-9]. In order to increase the sustained response rate, it is important to decline the viral load during the initial weeks of antiviral therapy because IFN-α dose administered is directly related with the decline of HCV RNA[10-13].

The aim of the present study was first to evaluate the efficacy as well as safety and tolerability of a high-dose IFN-α2b induction therapy in combination with ribavirin in patients who failed with interferon monotherapy and had a relapse. Further, the data were analyzed for potential predictive factors for a viral response in this subgroup of patients.

A total of 70 patients (49 males/21 females) with chronic hepatitis C (elevated ALT, HCV RNA positive) who failed IFN-α monotherapy (group A, n = 44) or had a relapse (group B, n = 26), were enrolled in the study. Other inclusion criteria included hemoglobin level > 120 g/L, white blood cell count > 2.5/nL, platelet count > 80/nL, and normal bilirubin, albumin and creatinine levels. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Exclusion criteria were decompensated liver cirrhosis (Child-Pugh B or C), autoimmune hypo- or hyperthyroidism, neuropsychiatric disorders, cardiovascular disease, HIV infection or infection with other hepatitis virus or other causes of liver disease, and pregnancy.

Seventy percent of all patients were infected with genotype 1a/b, 7% with genotype 2a/c, 20% with genotype 3a and 3% with genotype 4. Pre-treatment quantitative HCV RNA levels were determined using the Roche Cobas Amplicor v2.0 test. In 71% of patients a liver biopsy was performed and the degree of inflammation and fibrosis was estimated according to the Ishak-Knodell score. More details are listed in Table 1.

| All patients | Group A(non-responder) | Group B(relapser) | |

| Male (%) | 70 | 80.5 | 59 |

| Mean age | 40.4 | 39.6 | 41.8 |

| Genotype 1 (%) | 70 | 75 | 57 |

| Serum ALT (U/L) | 70 ± 2 | 67 ± 6 | 75 ± 10 |

| Viral load1 (%) | |||

| < 2 Mio copies/mL | 37 | 39 | 35 |

| > 2 Mio copies/mL | 63 | 61 | 65 |

| HAI score2 (%) | |||

| HAI score (0-1) | 72 | 68 | 77 |

| HAI score (3-4) | 28 | 32 | 23 |

This study was carried out as an open, randomized, multicenter study (three centers).

Patients were treated first with 10 MU IFN-α2b daily for 3 wk. After the induction phase, patients received 5 MU IFN-α2b TIW for 21 wk. If a negative HCV RNA PCR result was obtained, treatment was continued for the remaining 24 wk with 3 MU IFN-α2b TIW. Ribavirin was added at 1 000-1 200 mg (according to body weight of > or < 75 kg) at treatment wk 4 until wk 48 (Figure 1). The concept of a delayed onset of ribavirin was based on the observation that in the initial phase of antiviral therapy ribavirin has no significant effects on viral kinetics[14,15]. Thus the drug was given at a later time point to ameliorate side effects during the IFN high dose induction period. For severe adverse events other than anemia, interferon dosage was decreased (10 MU > 5 MU or 5 MU > 3 MU) or stopped if the actual dose was 3 MU. For anemia ( < 100 g/L), ribavirin dose was lowered to 600 mg/d, and discontinued if hemoglobin concentrations fell to < 85 g/L. If severe leuko- or thrombocytopenia (white blood cell count < 1 500/μL, platelet count < 40 000/μ L) occurred, interferon medication was stopped.

During the IFN-α2b high-dose induction phase, all patients were evaluated for tolerance, safety and treatment response twice weekly, while for the further follow-up patients were seen at wk 4, 8, 12, 18, 24, 36 and 48. At each visit, hematological, biochemical and HCV RNA testing was done.

When the treatment was completed, all patients were followed up for 48 wk.

Biochemical response was estimated after 12 wk of therapy and defined by a normalization of primary elevated ALT values. Undetectable serum HCV RNA at wk 24 during therapy was the criterion for an initial virological response. Virological end-of-treatment response was defined by a negative testing for HCV RNA at wk 48. If HCV RNA was still undetectable 24 wk after completion of the treatment, a virological sustained response was achieved.

The primary end point of the study was the comparison of virological response rates in relation to the prior response to the initial IFN-α monotherapy (non-responder vs relapser). Secondary parameters were differences in virological response rates in relation to genotype (genotype 1 vs non-1-genotypes) and viral kinetics (estimated after 12 wk of treatment). All safety and efficacy analyses were based on an intention-to-treat basis for all patients who received at least one dose of study medication. Statistical analysis was performed using χ2 and Fisher’s exact test (SPSS for Windows 10.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

According to the Declaration of Helsinki, a positive ethics committee approval was obtained. Patients were only included in this study after giving their written informed consent.

In 5 patients (7%), therapy was discontinued because of side effects such as insomnia, myalgia and fatigue (three patients) or because of a significant increase ( > 5 × ULN) in alanine aminotransferase levels (two patients). The IFN-α dosage was reduced in seven patients (10%) because of severe neutropenia ( < 1 500/μL). Average IFN-α induced a mean neutropenia of 2 695 ± 629/μ L and a mean thrombopenia of 119.700 ± 31.500/μL. Hemolytic anemia as a common side effect of ribavirin leads to a mean hemoglobin decrease of 3 ± 14.8 g/L in all patients. In four patients (5.7%), ribavirin was reduced because the hemoglobin value was persistently lower than 100 g/L.

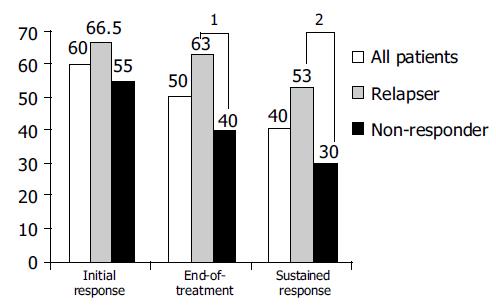

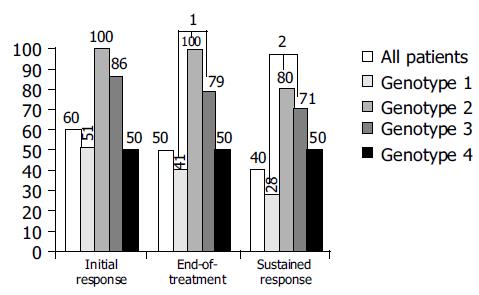

At wk 24, a biochemical response was observed in 85% and an initial virological response was achieved in 60% of all patients. Ten percent of patients had a break-through phenomenon after a previous negative HCV RNA PCR in serum in the first 24 wk of therapy. An end-of-treatment response (EOT) was achieved in 50% of all patients. During the follow-up, 10% of patients experienced a relapse. Accordingly, an overall sustained response (SR) of 40% was obtained. Patients with no primary response had a significant lower response rate than those with a former relapse (SVR 53% vs 30%; P = 0.049 (χ2 test; Figure 2)). Likewise, genotype 1a/b showed a significantly lower response rate than other genotypes (28% vs 74% for genotypes 2 and 3; P = 0.001 χ2 test; Figure 3).

To estimate the effect of a fast decline of viral load as a potential predictive factor for a viral response especially in former non-responders, HCV-RNA was analyzed after 12 wk of therapy in 40 patients. An early loss of HCV RNA level was significantly (P = 0.001; Fisher’s exact test) associated with higher sustained response rates as all patients with a late negative HCV RNA testing ( > 12 wk of therapy), experienced a breakthrough or relapse during further follow-up. In contrast, 65% of all patients with a rapid drop of HCV RNA level and a negative PCR result at wk 12, finally experienced a sustained viral response (Table 2). No correlation between the observed decline of viral load and the result of previous treatment (relapse or non-response) or initial viral load could be demonstrated in this small subgroup in the present study.

| Treatment week | “Fast responder” (HCV RNA negative at wk 12, n = 31) | “Slow responder” (HCV RNA negative after wk 12, n = 9) | P |

| 48 (ETR, %) | 25 patients PCR negative (81) | 3 patients PCR negative (33) | 0.0121 |

| Follow-up (SR, %) | 20 patients PCR negative (65) | 0 patient PCR negative (0) | 0.0011 |

Therapy of patients who failed with IFN-α monotherapy and had a relapse remains a difficult issue though the advances have been achieved with the introduction of ribavirin combination therapy as well as the introduction of pegylated interferons. Retreatment of this patient group with standard doses (TIW) of interferon plus ribavirin especially in non-responders or patients infected with genotype 1 was largely ineffective, resulting in SVR of 12-16%[5,6]. Even when treated with the pegylated interferons-α2a or -α2b, the sustained response rate was between 14% and 27%[7-9].

Many studies have shown the importance of a rapid initial decline of viral load in obtaining a better response rate[10,11]. Higher INF-α dosage is correlated with a faster decline of the viral load[12,13]. Based on these observations, this study using an induction therapy with 10 MU IFN-α daily was designed. To reduce the extent of expected side effects, ribavirin was subsequently added at the end of the IFN-α induction phase (end of wk 3).

The interferon induction phase with 10 MU IFN-α2b daily for over 3 wk was safe and at least moderately tolerated. Treatment was discontinued only in 7% of patients, interferon or ribavirin was reduced in 16% of patients, mainly because of hematological side effects. In comparison to other studies using high-dose interferon induction therapy in combination with non-pegylated interferons[16-19], the sustained response rate in the present study was higher (30% vs 6-27%) , perhaps as a result of the higher initial IFN dose or a longer induction period leading to a faster decline in serum HCV RNA level. Another reason for the relatively higher sustained response rate in the present trial may be due to the low dropout rate (7%) in comparison to other treatment schedules (15-21.9%) using a higher dose of INF-α.

The sustained response rate was significantly lower in patients with no former response than in relapsers (30% vs 53%; P = 0.049). Possible reasons for these observations might be the higher number of patients infected with genotype 1, male gender and a higher Ishak score of 3-4 in the non-responder group. These viral and host characteristics are known as negative predictive factors for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C[18,19]. Independent of these factors other studies have also shown higher response rates in patients with an earlier relapse than in non-responders after INF-α monotherapy[17,20].

All former non-responders with a sustained response had a negative serum HCV RNA at treatment wk 12, which underscores the importance of a fast decline in viral load and may serve as a rationale in using higher initial interferon doses especially in treating non-responders[21-23]. However, in patients with genotype 1, sustained response rates were significantly lower in those with other HCV types. These observations are due to multiple factors, including higher drug effectiveness, a faster free virion clearance rate and possibly an enhanced immunological response in patients infected with non-1 genotype[24].

As one explanation for the differences in viral kinetics between the HCV subgroups, it has been speculated that HCV genotype 1 is not as sensitive to IFN-α as other viral strains[25,26]. As described above and shown in the large registration trials for treatment of naive patients with pegylated interferons[27], an early therapeutic decision regarding the continuation of treatment at 12 wk appears also to be amenable in non-reponders.

At present, pegylated interferons in combination with ribavirin can improve the sustained response rate of about 50-56% in naive HCV positive patients. The subgroup of genotype 1/high viral load patients, however, did not show improved sustained response rates of 30-34% when treated with pegylated interferons. Furthermore, patients who failed the standard interferon and ribavirin therapy did not show significant sustained response rates when retreated with pegylated interferons (SVR 6-12%). Thus, the sustained response rate reported in this study together with good tolerability using a standard daily interferon dose makes this type of treatment a valuable alternative for this difficult-to-treat patient group. An even longer high-dose induction period for more than 3 wk may lead to an even higher sustained response rate, but this might be counterbalanced by a relatively lower tolerability. For a final evaluation of the optimal duration of induction, larger clinical trials are needed.

Science Editor Wang XL and Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK

| 1. | Purcell RH. Hepatitis viruses: changing patterns of human disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2401-2406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wiesner RH, Lombardero M, Lake JR, Everhart J, Detre KM. Liver transplantation for end-stage alcoholic liver disease: an assessment of outcomes. Liver Transpl Surg. 1997;3:231-239. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Davis GL, Balart LA, Schiff ER, Lindsay K, Bodenheimer HC, Perrillo RP, Carey W, Jacobson IM, Payne J, Dienstag JL. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C with recombinant interferon alfa. A multicenter randomized, controlled trial. Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1501-1506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1213] [Cited by in RCA: 1130] [Article Influence: 31.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Schiff ER, Shiffman ML, Lee WM, Rustgi VK, Goodman ZD, Ling MH, Cort S, Albrecht JK. Interferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1485-1492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2509] [Cited by in RCA: 2434] [Article Influence: 90.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Barbaro G, Di Lorenzo G, Soldini M, Giancaspro G, Bellomo G, Belloni G, Grisorio B, Annese M, Bacca D, Francavilla R. Interferon-alpha-2B and ribavirin in combination for chronic hepatitis C patients not responding to interferon-alpha alone: an Italian multicenter, randomized, controlled, clinical study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:2445-2451. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Sostegni R, Ghisetti V, Pittaluga F, Marchiaro G, Rocca G, Borghesio E, Rizzetto M, Saracco G. Sequential versus concomitant administration of ribavirin and interferon alfa-n3 in patients with chronic hepatitis C not responding to interferon alone: results of a randomized, controlled trial. Hepatology. 1998;28:341-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sulkowski M, Rothstein K, Stein L, Godowsky E, Goodman R, Dieterich D; PEG-Interferon alfa-2B Ribavirin for Treat-ment of patients with chronic Hepatitis C who have previ-ously failed to achieve a sustained virologic response follow-ing Interferon alfa or Interferon alfa-2B Ribavirin Therapy [abstract]. DDW (Orlando 2003). . |

| 8. | Jacobson IM, Ahmed F, Russo MW, Brown RS, Lebovics E, Min A, Esposito S, Brau N, Tobias H, Klion F; Pegylated Interferon alfa-2B plus Ribavirin in patients with chronic Hepatitis C: A trial in prior Nonresponders to Interferon Monotherapy or Combination Therapy and in Combination Therapy Relapsers: Final Re-sults [abstract]. DDW (Orlando 2003). . |

| 9. | Lawitz EJ, Bala NS, Becker S, Brown G, Davis M, Dhar R, Ganeshappa KP, Gordon S, Holtzmuller K, Jeffries M; Pegylated Interferon alfa 2B and Ribavirin for Hepatitis C Patients who were Nonresponders to previous Therapy [abstract]. DDW (Orlando 2003). . |

| 10. | Karino Y, Toyota J, Sugawara M, Higashino K, Sato T, Ohmura T, Suga T, Okuuchi Y, Matsushima T. Early loss of serum hepatitis C virus RNA can predict a sustained response to interferon therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:61-65. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Fried MW, Shiffman M, Sterling RK, Weinstein J, Crippin J, Garcia G, Wright TL, Conjeevaram H, Reddy KR, Peter J. A multicenter, randomized trial of daily high-dose interferon-alfa 2b for the treatment of chronic hepatitis c: pretreatment stratification by viral burden and genotype. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3225-3229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Neumann AU, Lam NP, Dahari H, Gretch DR, Wiley TE, Layden TJ, Perelson AS. Hepatitis C viral dynamics in vivo and the antiviral efficacy of interferon-alpha therapy. Science. 1998;282:103-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1604] [Cited by in RCA: 1451] [Article Influence: 53.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lam NP, Neumann AU, Gretch DR, Wiley TE, Perelson AS, Layden TJ. Dose-dependent acute clearance of hepatitis C genotype 1 virus with interferon alfa. Hepatology. 1997;26:226-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Dixit NM, Layden-Almer JE, Layden TJ, Perelson AS. Modelling how ribavirin improves interferon response rates in hepatitis C virus infection. Nature. 2004;432:922-924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 293] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Saab S, Hu R, Ibrahim AB, Goldstein LI, Kunder G, Durazo F, Han S, Yersiz H, Ghobrial RM, Farmer DG. Discordance between ALT values and fibrosis in liver transplant recipients treated with ribavirin for recurrent hepatitis C. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:328-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ferenci P, Stauber R, Steindl-Munda P, Gschwantler M, Fickert P, Datz C, Müller C, Hackl F, Rainer W, Watkins-Riedel T. Interim analysis of a randomized controlled trial of combination of ribavirin and high dose interferon-alpha in interferon nonresponders with chronic hepatitis C. J Viral Hepat. 1999;6 Suppl 1:53-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Min AD, Jones JL, Esposito S, Lebovics E, Jacobson IM, Klion FM, Goldman IS, Geders JM, Tobias H, Bodian C. Efficacy of high-dose interferon in combination with ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C resistant to interferon alone. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1143-1149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Poynard T, Marcellin P, Lee SS, Niederau C, Minuk GS, Ideo G, Bain V, Heathcote J, Zeuzem S, Trepo C. Randomised trial of interferon alpha2b plus ribavirin for 48 weeks or for 24 weeks versus interferon alpha2b plus placebo for 48 weeks for treatment of chronic infection with hepatitis C virus. International Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group (IHIT). Lancet. 1998;352:1426-1432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1667] [Cited by in RCA: 1640] [Article Influence: 60.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tong MJ, Reddy KR, Lee WM, Pockros PJ, Hoefs JC, Keeffe EB, Hollinger FB, Hathcote EJ, White H, Foust RT. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C with consensus interferon: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Consensus Interferon Study Group. Hepatology. 1997;26:747-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Di Marco V, Almasio P, Vaccaro A, Ferraro D, Parisi P, Cataldo MG, Di Stefano R, Craxì A. Combined treatment of relapse of chronic hepatitis C with high-dose alpha2b interferon plus ribavirin for 6 or 12 months. J Hepatol. 2000;33:456-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zeuzem S, Feinman SV, Rasenack J, Heathcote EJ, Lai MY, Gane E, O'Grady J, Reichen J, Diago M, Lin A. Peginterferon alfa-2a in patients with chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1666-1672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 883] [Cited by in RCA: 851] [Article Influence: 34.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bekkering FC, Brouwer JT, Leroux-Roels G, Van Vlierberghe H, Elewaut A, Schalm SW. Ultrarapid hepatitis C virus clearance by daily high-dose interferon in non-responders to standard therapy. J Hepatol. 1998;28:960-964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Di Marco V, Vaccaro A, Ferraro D, Alaimo G, Rodolico V, Parisi P, Peralta S, Di Stefano R, Almasio PL, Craxì A. High-dose prolonged combination therapy in non-responders to interferon monotherapy for chronic hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:953-958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Neumann AU, Lam NP, Dahari H, Davidian M, Wiley TE, Mika BP, Perelson AS, Layden TJ. Differences in viral dynamics between genotypes 1 and 2 of hepatitis C virus. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:28-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Enomoto N, Sakuma I, Asahina Y, Kurosaki M, Murakami T, Yamamoto C, Izumi N, Marumo F, Sato C. Comparison of full-length sequences of interferon-sensitive and resistant hepatitis C virus 1b. Sensitivity to interferon is conferred by amino acid substitutions in the NS5A region. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:224-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 459] [Cited by in RCA: 452] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gale MJ, Korth MJ, Katze MG. Repression of the PKR protein kinase by the hepatitis C virus NS5A protein: a potential mechanism of interferon resistance. Clin Diagn Virol. 1998;10:157-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Berg T, Sarrazin C, Herrmann E, Hinrichsen H, Gerlach T, Zachoval R, Wiedenmann B, Hopf U, Zeuzem S. Prediction of treatment outcome in patients with chronic hepatitis C: significance of baseline parameters and viral dynamics during therapy. Hepatology. 2003;37:600-609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |