Published online Sep 7, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i33.5226

Revised: December 5, 2004

Accepted: December 9, 2004

Published online: September 7, 2005

Intra-abdominal fibromatosis (IAF) is a benign mesenchymal lesion that can occur throughout the gastrointestinal tract. Although rare, it is the most common primary tumor of the mesentery and can develop at any age. We describe a rare case of primary IAF involving the mesentery and small bowel which clinically, macroscopically and histologically mimicked malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). This report highlights the fact that benign IAF can be misdiagnosed as a malignant GIST localized in the mesentery or arising from the intestinal wall. Their diagnostic discrimination is essential because of their very different biological behaviors and the fact that the introduction of effective therapies involving tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI571 (imatinib mesylate) has greatly changed the clinical approach to intra-abdominal stromal spindle cell tumors.

- Citation: Colombo P, Rahal D, Grizzi F, Quagliuolo V, Roncalli M. Localized intra-abdominal fibromatosis of the small bowel mimicking a gastrointestinal stromal tumor: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(33): 5226-5228

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i33/5226.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i33.5226

Although rare in humans, intra-abdominal fibromatosis (IAF) is the most common primary mesenteric tumor with spindle cell morphology. It may occur at any age, can be solitary or multiple, and may involve the small bowel, omentum, mesocolon and/or retroperitoneum[1,2]. It can sometime mimic the clinical characteristics, radiological imaging and histopathological appearance of a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), thus leading to an incorrect diagnosis.

It has been clearly established that GISTs originate from gastrointestinal pacemaker Cajal cells, which are the primary effectors controlling gut motility[7,8]. Although they have been considered as a distinct tumoral entity for about 10 years, they can now be more precisely identified as a result of the widespread use of immunohistochemistry with c-kit (CD117, a protein synthesized in interstitial Cajal cells) for the diagnostic analysis of spindle cell lesions of the mesentery and gastrointestinal tract. This marker has emerged as their most important defining feature, and is probably the gold standard for GIST diagnosis[2]. c-kit gene mutations and kit protein overexpression also seem to be essential for the pathogenesis of GISTs[9].

We describe here a rare, localized variant of primary IAF involving the mesentery and small bowel, which mimicked a GIST by strongly expressing the c-kit protein. Because of the remarkably overlapping immunophenotype of the two lesions, the aim of this report is to highlight the need to discriminate them because of the introduction of specific therapeutic strategies and the fact that they have different biological behaviors: IAF is benign and exclusively locally aggressive, whereas GISTs are malignant and may lead to distant metastases.

A 50-year-old white man with recent weight loss was admitted to Istituto Clinico Humanitas (Rozzano, Milan, Italy) because of abdominal discomfort in the left iliac fossa and suprapubic region, and sub-occlusive symptoms. He had undergone a partial sigmoid resection to treat perforated diverticular disease, one year before.

During the instrumental evaluation of suspected recurrent diverticulitis, abdominal ultrasound analysis revealed a mass involving the small bowel loops, and computed tomography (CT) demonstrated the presence of a round, lobulated, suprapubic neoplasm in the mesenteric region near the small bowel, that was presumably its site of origin (Figure 1). On the basis of the available clinical data and radiological imaging, an initial hypothesis of malignant GIST was made.

After surgical exploration of the abdominal cavity, the ileal tract with the tumoral mass and the adjacent mesenteric adipose tissue were excised. No other signs of disease were found in the other abdominal organs.

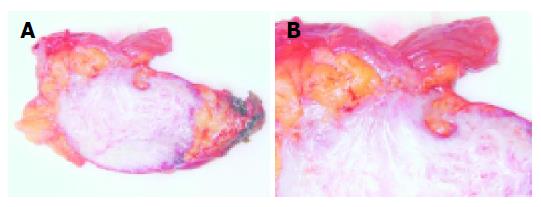

Macroscopic examination of the specimen revealed a 7 cm×5 cm×5 cm encapsulated, well-circumscribed, firm, tan-gray mass infiltrating the adipose tissue and bowel wall (Figure 2).

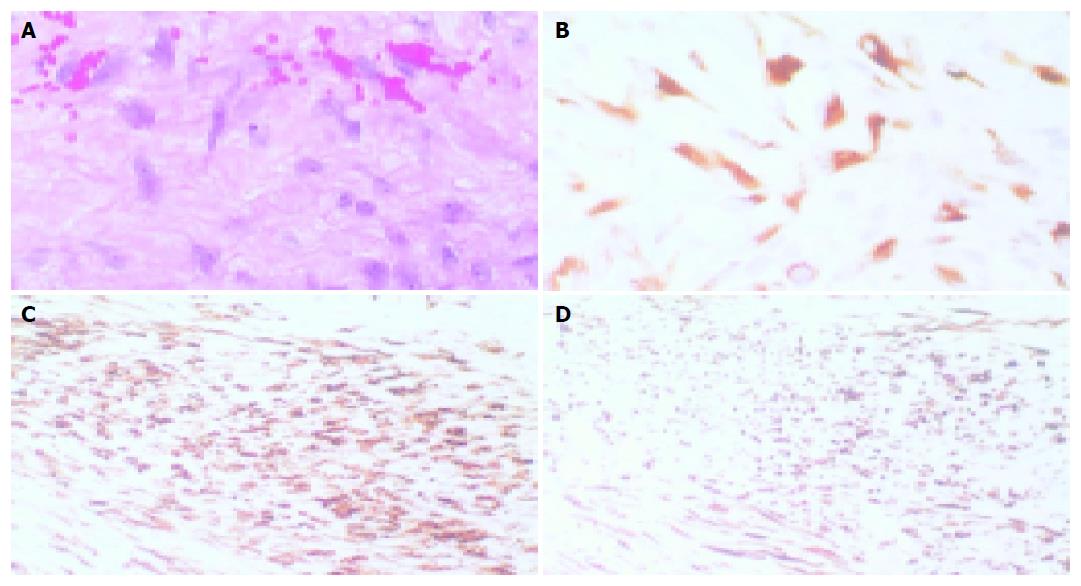

Light microscopy showed a neoplasm with a prevalently hypocellular appearance consisting of spindle cells growing in long sweeping fascicles. At higher magnification, the neoplastic population was found to consist of uniformly shaped cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and delicate, sometimes plump, nuclei with clearly evident nucleoli (Figure 3A). The mitotic activity index ranged from 1 to 10 mitoses/50 high power fields in the hypercellular areas.

The presence of these hypercellular areas with partially circumscribed borders, and the infiltration spreading to the muscularis propria of the small bowel, consistently favored a microscopic diagnosis of GIST, thus supporting the clinical, radiological and macroscopic findings.

However, this hypothetical diagnosis was not supported by the generally hypocellular growth pattern, the digitiform infiltration margins inside the adjacent fat tissue, and the absence of foci of necrosis, hemorrhages or cysts. Immunohistochemistry showed that the cells making up the lesion were immunopositive for c-kit protein (Figure 3B), and some were positive for smooth muscle actin (Figure 3C) and desmin (Figure 3D); however, no CD34 or S100 expression was ever found.

The final diagnosis was localized IAF of the mesentery and small bowel. A control CT scan, 6 mo after surgery, showed no signs of recurrent disease.

Primary IAF of the mesentery is a rare variant of benign stromal neoplasms of fibroblast-myofibroblast origin that may arise ex novo, but is usually secondary to trauma or hormonal stimulation, or associated with familial polyposis coli or Gardner’s syndrome[1-6]. This neoplastic disease most frequently occurs in the anterior abdominal wall, and is usually treated exclusively by means of surgical excision with a wide margin of uninvolved tissue; however, local recurrences due to incomplete resection have been described in an estimated 16% of cases, leading to intestinal obstruction and death in 6%[2].

Although it is generally easy to diagnose primary IAF, the localized tumor growth and its apparent source in the bowel wall may lead to misinterpretations and clinical, radiological, macroscopic and microscopic hypotheses of a GIST (a mesenchymal tumor of the gastrointestinal tract).

The case presented here had a number of additional characteristics usually found in GISTs, such as c-kit cytoplasmic immunoreactivity, the fascicular arrangement of neoplastic cells with well-circumscribed borders, with many mitotic figures and cytological atypia with plump nuclei and prominent nucleoli.

However, light microscopy evaluation of the available tissue sections revealed the morphological features of fibromatosis, which can be summarized as: (a) spindle cells oriented along their long axis; (b) broad sweeping fascicles of varying cellularity with abundant collagenous stroma; (c) the absence of necrosis, hemorrhages, cysts and skenoid fibers deposits; and (d) the protrusion of the tumor into the lumen and ulceration of the overlying mucosa. Moreover, according to Monihan et al., the absence of CD34 and S100 expression supports the fibromatous nature of the lesion and highlight the fact that these proteins may be helpful in discriminating IAF from GIST[10].

Yantiss et al., have recently underlined the importance of making a more complete evaluation in order to distinguish these two very different neoplastic lesions, putting greater emphasis in their clinical, radiological, macroscopic, histological, immunophenotypical and ultrastructural features[11].

GISTs are potentially misdiagnosed as localized IAF arising within or involving the bowel wall, and their immunophenotypes may vary and overlap[1,2]. The overexpression of c-kit protein has been found in a large number of mesenchymal, epithelial and hematopoietic neoplasms, including fibromatosis, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, synovial sarcoma, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, glioma and germinoma[12]. These findings all confirm that c-kit, smooth muscle actin and desmin cannot help in differential diagnosis and their immunoreactivity must be interpreted in conjunction with the morphological analysis and clinical evaluation. In cases such as the one reported here, the clinical and histological differential diagnosis with GIST are mandatory, above all in the light of the current criteria predicting GIST outcomes (the number of mitoses and the size of the lesion), which classified our case as being at intermediate/high risk of sarcoma, which would require the consideration of a further therapeutic approach[13].

It is now well known that fibromatosis expresses c-kit, against which STI571 (imatinib mesylate) is a target-based molecule that has remarkable clinical effects and is well tolerated by patients with non-resectable GISTs or non-resectable extra-abdominal desmoid tumors[9]; however, the potential therapeutic role of this small molecule in IAF is still unclear.

In conclusion, although intra-abdominal lesions with spindle cell morphology are relatively rare, and similarities in their clinical data and radiological and histological appearances may lead to misdiagnoses, it is also true that tumor diagnoses based on immunohistochemical staining or traditional histological criteria alone are not specific enough[4].

Our report highlight the need for reliable new criteria for discriminating IAF and GIST because of the introduction of sophisticated therapeutic strategies (in order to select patients to be admitted to clinical trials) and their different biological behaviors: IAF is benign and exclusively locally aggressive, whereas GISTs are malignant and potentially capable of leading to distant metastases.

Science Editor Zhu LH and Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK

| 1. | Burke AP, Sobin LH, Shekitka KM, Federspiel BH, Helwig EB. Intra-abdominal fibromatosis. A pathologic analysis of 130 tumors with comparison of clinical subgroups. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14:335-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Al-Nafussi A, Wong NA. Intra-abdominal spindle cell lesions: a review and practical aids to diagnosis. Histopathology. 2001;38:387-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gardner EJ. A genetic and clinical study of intestinal polyposis, a predisposing factor for carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Am J Hum Genet. 1951;3:167-176. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Dong-Heup K, Kim DH, Goldsmith HS, Quan SH, Huvos AG. Intra-abdominal desmoid tumor. Cancer. 1971;27:1041-1045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nichols RW. Desmoid tumors: a report of 31 cases. Arch Surg. 1923;7:227-236. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Reitano JJ, Scheinin TM, Hayry P. The desmoid syndrome: new aspects in the cause, pathogenesis and treatment of the desmoid tumor. Am J Surg. 1986;151:230-237. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 345] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kindblom LG, Remotti HE, Aldenborg F, Meis-Kindblom JM. Gastrointestinal pacemaker cell tumor (GIPACT): gastrointestinal stromal tumors show phenotypic characteristics of the interstitial cells of Cajal. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:1259-1269. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Robinson TL, Sircar K, Hewlett BR, Chorneyko K, Riddell RH, Huizinga JD. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors may originate from a subset of CD34-positive interstitial cells of Cajal. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1157-1163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lin SC, Huang MJ, Zeng CY, Wang TI, Liu ZL, Shiay RK. Clinical manifestations and prognostic factors in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2809-2812. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Monihan JM, Carr NJ, Sobin LH. CD34 immunoexpression in stromal tumours of the gastrointestinal tract and in mesenteric fibromatoses. Histopathology. 1994;25:469-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yantiss RK, Spiro IJ, Compton CC, Rosenberg AE. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor versus intra-abdominal fibromatosis of the bowel wall: a clinically important differential diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:947-957. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hurlimann J, Gardiol D. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: an immunohistochemical study of 165 cases. Histopathology. 1991;19:311-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mace J, Sybil Biermann J, Sondak V, McGinn C, Hayes C, Thomas D, Baker L. Response of extraabdominal desmoid tumors to therapy with imatinib mesylate. Cancer. 2002;95:2373-2379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |