Published online May 7, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i17.2687

Revised: May 26, 2004

Accepted: August 21, 2004

Published online: May 7, 2005

The gastrointestinal tract (GIT) is a common site of metastases for malignant melanoma. These metastatic tumors are often asymptomatic. We describe a case of a 58-year-old male who presented with a sudden onset of generalized abdominal pain. The patient’s past medical history was significant for lentigo melanoma of the right cheek. Laparotomy was performed and two segments of small bowel, one with a perforated tumor, the other with a non-perforated tumor, were removed. Histology and immunohistochemical staining revealed the perforated tumor to be a metastatic malignant melanoma and the non-perforated tumor was found to be a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). The patient was discharged 7 d postoperatively. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case in the literature of a simultaneous metastatic malignant melanoma and a GIST. Surgical intervention is warranted in patients with symptomatic GIT metastases to improve the quality of life or in those patients with surgical emergencies.

- Citation: Brummel N, Awad Z, Frazier S, Liu J, Rangnekar N. Perforation of metastatic melanoma to the small bowel with simultaneous gastrointestinal stromal tumor. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(17): 2687-2689

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i17/2687.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i17.2687

The gastrointestinal tract (GIT) is a common site of metastases for malignant melanoma[1-4]. These metastatic tumors are often asymptomatic. Occasionally, however, they may cause symptoms. With small bowel metastases, small bowel obstruction from intussusception due to submucosal lesions is the most common clinical presentation[2]. Perforation, however, is rare[2]. We herein present a case of metastatic melanoma to the small bowel presenting with acute abdominal pain due to perforation.

A 58-year-old white male presented with a 1-d history of sudden onset generalized abdominal pain. He denied any previous history of abdominal pain or other GI complaints. A plain film of the abdomen revealed dilated loops of small bowel, CT of the abdomen and pelvis showed a partially enhancing mass in the small bowel as well as free air under the diaphragm.

The patient’s past medical history was significant for lentigo melanoma of the right cheek 12 years ago. Two and a half years ago he underwent a right lower lobectomy for a 5.5-cm lesion of the right lung. Histology revealed a nodule of metastatic malignant melanoma adjacent to the hilum of the right lower lung lobe. One month after the lobectomy, a CT of the head showed a focal enhancing lesion in the posterior temporal region and a small enhancing lesion in the left hemisphere adjacent to the falx, consistent with metastases to the brain. Thoracic and abdominal CT revealed a soft tissue density in the midportion of the lower abdomen that resembled a soft tissue nodule adjacent to a small bowel loop, likely in the mesentery. However, it could not be determined if the lesion was merely an unopacified bowel loop or a metastatic nodule.

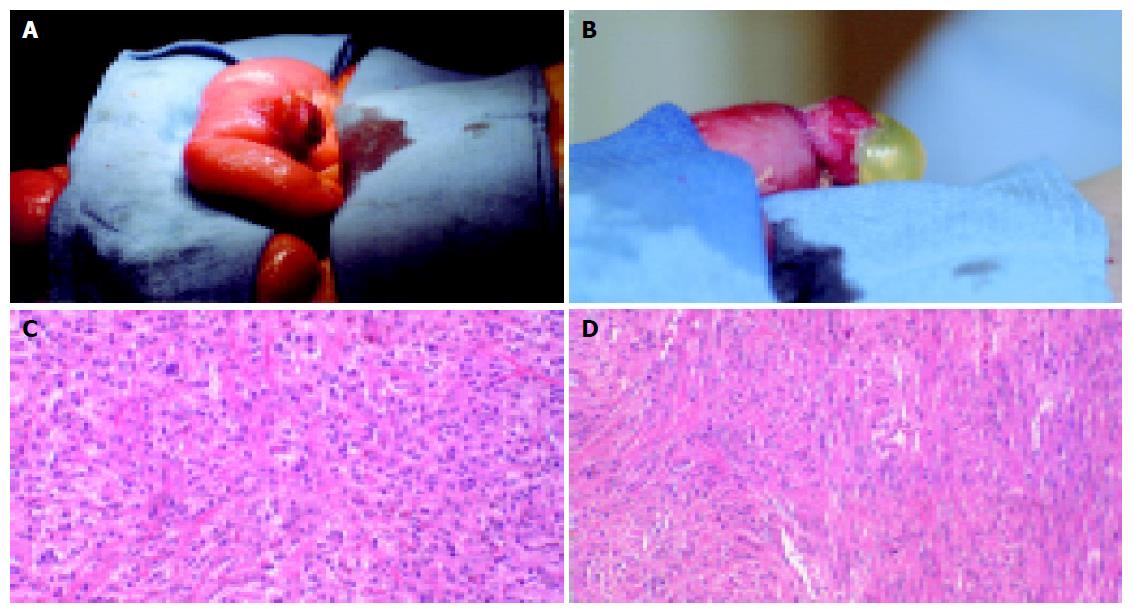

The patient underwent an emergent exploratory laparotomy which showed perforation of a small bowel tumor approximately 2 feet distal to the ligament of Treitz (Figure 1A). In addition, a similar, but nonperforated lesion was seen approximately 2-feet distal to the first lesion (Figure 1B). Both tumors were resected and the bowel continuity was restored using stapled anastamoses. The patient’s recovery was uncomplicated, and the patient was discharged 7 d postoperatively.

Microscopic examination of the two masses showed two morphologically different tumors. The proximal tumor showed a malignant neoplasm forming nests and sheets extending from the mucosal to the serosal bowel layers. Individual cells showed highly pleomorphic nuclei with prominent, sometimes multiple, nucleoli and abundant pale eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 1C). Immunohistologic staining of this tumor was positive for S100, HMB 45 and vimentin, indicating malignant metastatic melanoma. The second lesion also involved the full thickness of the bowel wall. Tumor cells were spindled and arranged in fascicles. Individual cells showed mildly pleomorphic nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 1D). The distal tumor stained positive for S100, vimentin, actin, CD 34 and CD 117, and notably was negative for HMB 45, indicating that the second tumor was a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST).

Metastatic melanoma is the most common metastatic tumor found in the GIT[1,3]. In one case series, melanoma commonly metastasized to the liver (68%), small intestine (58%), the colon (22%), and the stomach (20%)[5]. These metastases are discovered before death in only between 0.9% and 4.4% of patients with a diagnosis of primary melanoma[4,5].

GIT metastases are difficult to detect with imaging studies. Bender et al[6], examined abdominal CT scans and small bowel follow through studies of patients with surgically excised GIT metastases. They found that these imaging studies were unreliable methods of detecting GIT metastases (CT scan: 66% sensitivity; small bowel follow through: 58% sensitivity).

A limited number of GIT metastases causing bowel perforation have been described in the literature. Klausner et al[5], described a case of small bowel perforation secondary to GIT metastases in a 49-year-old male who survived for 6 mo after bowel and tumor resection. Three additional cases were described by Goodman et al[6]; however, only one case of small bowel perforation was discovered intraoperatively. The other two cases occurred in patients not considered good surgical candidates due to the advanced nature of their disease. These patients subsequently died from bowel perforation and resulting infection[6]. Geboes et al[4], describes one patient with symptomatic GIT metastases, who died from perforat-ion. However, the location of the bowel perforation was not reported.

Relief of symptoms can be achieved with surgical resection of the GIT metastases. Goodman and Karakousis reported 22 cases of symptomatic metastatic melanoma to the GIT[7]. Sixteen of their patients underwent surgery to relieve symptoms or for improvement in quality of life. These patients survived an average of 4½ mo after resection of their GI metastases. They recommended resection of GIT metastases for uncontrolled or repeated GI hemorrhage, recurrent severe abdominal pain suggestive of recurrent intussusception, and in cases of clinically evident intestinal obstruction.

The association between mutation of the c-kit gene and cutaneous hyperpigmentation is well known[8,9]; however, the simultaneous presence of a metastatic melanoma and GIST in the same patient, to the best of our knowledge, has not been reported. One case of an omental GIST in a patient with a history of melanoma was described[10]. The authors hypothesize that the occurrence of both omental GIST and melanoma could suggest an association or just a mere coincidence. In our case report, the fact that the patient has both a metastatic melanoma and GIST could suggest a pathogenic role of mutation in the c-kit gene.

In conclusion, GIT metastases are common in patients with malignant melanoma. They are often asymptomatic or may present with non-specific symptoms. Surgical intervention is warranted in patients with symptomatic GIT metastases to improve quality of life or in those patients who present with surgical emergencies. Routine resection of asymptomatic GIT metastases, however, cannot be recommended.

Science Editor Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK

| 1. | Capizzi PJ, Donohue JH. Metastatic melanoma of the gastrointestinal tract: a review of the literature. Compr Ther. 1994;20:20-23. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Schuchter LM, Green R, Fraker D. Primary and metastatic diseases in malignant melanoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Curr Opin Oncol. 2000;12:181-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Blecker D, Abraham S, Furth EE, Kochman ML. Melanoma in the gastrointestinal tract. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3427-3433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Geboes K, De Jaeger E, Rutgeerts P, Vantrappen G. Symptomatic gastrointestinal metastases from malignant melanoma. A clinical study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1988;10:64-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Klausner JM, Skornick Y, Lelcuk S, Baratz M, Merhav A. Acute complications of metastatic melanoma to the gastrointestinal tract. Br J Surg. 1982;69:195-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bender GN, Maglinte DD, McLarney JH, Rex D, Kelvin FM. Malignant melanoma: patterns of metastasis to the small bowel, reliability of imaging studies, and clinical relevance. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2392-2400. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Goodman PL, Karakousis CP. Symptomatic gastrointestinal metastases from malignant melanoma. Cancer. 1981;48:1058-1059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Maeyama H, Hidaka E, Ota H, Minami S, Kajiyama M, Kuraishi A, Mori H, Matsuda Y, Wada S, Sodeyama H. Familial gastrointestinal stromal tumor with hyperpigmentation: association with a germline mutation of the c-kit gene. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:210-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Babin RW, Ceilley RI, DeSanto LW. Oral hyperpigmentation and occult malignancy--report of a case. J Otolaryngol. 1978;7:389-394. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Cai N, Morgenstern N, Wasserman P. A case of omental gastrointestinal stromal tumor and association with history of melanoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 2003;28:342-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |