INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis B virus is a severe infectious pathogen causing chronic liver diseases and increasing risk of hepatocellular carcinoma[1]. Although recombinant vaccines are widely available[2], HBV infection is still a big challenge to the societies all over the world. Until now, interferon-α and nucleoside analogs, such as lamivudine, are of the few drugs capable of inhibiting HBV replication. However, interferon treatment usually results in a limited percentage of complete response and relapses generally occur without further treatment. Lamivudine, a strong inhibitor of HBV’s reverse-transcriptase, has been proved to be highly effective in blocking its genome replication. Nevertheless, a significant portion of patients relapsed after cessation of treatment. With prolonged treatment, escape mutants would develop[3].

RNA interference is a newly discovered phenomenon present in almost all eukaryotes[4,5]. It is activated by dsRNA, which is subsequently cleaved by Dicer into 21-23 nt small interfering RNAs (siRNA). The siRNAs are then unwound by RISC (siRNA induced silencing complex) in the presence of ATP. The activated RISC binds to and degrades target mRNA guided by the single strand siRNA. In mammals, long dsRNA can activate protein kinase R (PKR) and RNaseL, which are key components of the interferon signaling pathway, thus causing unspecific effects, whereas 21-23 nt siRNAs are short enough to bypass them[6]. Many studies have been carried out to silence a number of RNA viruses by RNA interference, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis C virus (HCV) and poliovirus, etc[7-11]. As hepatitis B virus (HBV) utilizes pregenomic RNA for synthesis of viral DNA via reverse transcription, it is also an ideal candidate for RNAi. Recently, vector-based RNAi technique, which uses endogenous U6 or H1 promoter to generate small interfering RNA (siRNA) in vivo, has become a new and economical system to achieve gene silencing[12,13]. In this study, we investigated whether vector-based siRNA promoted by U6 (pSilencer1.0-U6) could efficiently inhibit HBV replication in cell culture.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

TRIzol reagent, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), fetal calf serum and antibiotics were from GIBCO BRL. Restriction endonucleases were supplied by MBI Fermentas. SuperScript II reverse transcriptase was from Invitrogen, Carlsbad. DNA sequence primers were synthesized by CASarray, Shanghai. pSilencer 1.0-U6 was from Ambion, Austin. HBsAg and HBeAg ELISA kit were purchased from Shanghai SIIC Kehua Biotech. pHBV3.8 plasmid encoding the whole transcript of HBV DNA (adr subtype) from the core promoter to the polyA signal region (nucleotides 1403-3215 plus 1 to 1987), was constructed as a 1.2 copy insert of the full-length HBV genome into vector Pbs + (Stratagene) via restriction enzyme EcoRI and PstI sites (kindly provided by Professor. Yuan Wang, Institute of Biochemistry, Academia Sinica, Shanghai). After transfected into Huh-7 cells, the pHBV3.8 could express both HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) and E antigen (HBeAg), and the replication of HBV could be initiated. Plasmid pcDNA-CAT containing the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) gene under control of the CMV promoter was co-transfected as internal control. The expression of CAT could be measured by CAT ELISA kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany).

Cell culture and transfection

Huh-7 cell line was maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 100 mL/L fetal calf serum, 2 mmol/mL L-glutamine,100 µg/mL penicillin and 100 units/mL streptomycin (GIBCO BRL). The cells were incubated in a humidified incubator at 37 °C containing 50 mL/L CO2. Cell viability was estimated by the trypan blue dye exclusion method. Huh-7 cells were transfected using FuGENE6 cationic liposome (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), and cells were harvested 48 h and 72 h after transfection, respectively. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Target sequence selection and insertion sequence synthesis

By aligning different subtypes of HBV genome and using the Ambion web-based software, we selected 3 regions of high conservation designated as si-HBV1, 2 and 3 to be the target sequence. The target sequence of si-HBV1 was located in S region as well as P region of the HBV genome (nt 310 to 328), si-HBV2 and 3 were both in the C region (nt 1868 to 1886 for HBV2, nt 2373 to 2391 for HBV3). si-HBV1, 2 and 3 had the siRNA sequences completely identical to the target sequence of pHBV3.8. To create pSilencer plasmids, we used the primers: 5’-TTCGCAGTCCCCAACCTCCTTCAAGAGAGGAGGTTGG GGACTGCGAATTTTTT-3’ (sense) and 5’-AGCTAAAAAATT CGCAGTCCCCAACCTCCTCTCTTGAAGGAGGTTGGGGACTG CGAAGGCC-3’ (antisense) for pSi-HBV1; 5’-GCCTCCAAGC TGTGCCTTGTTCAAGAGACAAGGCACAGCTTGGAGGCTTTT TT-3 ’ (sense) and 5’AGCTAAAAAAGCCTCCAAGCTGTGCC TTGTCTCTTGAACAAGGCACAGCTTGGAGGCGGCC-3’ (antisense) for pSi-HBV2; 5’-GAAGAACTCCCTCGCCTCGTT CAAGAGACGAGGCGAGGGAGTTCTTCTTTTTT-3’(sense) and 5’AGCTAAAAAAGAAGAACTCCCTCGCCTCGTCTCT TGAACGAGGCGAGGGAGTTCTTCGGCC-3’ (antisense) for pSi-HBV3.

In this study, the target sequences used by Shlomai et al[14] for pSuper core1 (nt 2191 to 2209) and pSuper X (nt 1649 to 1667) were also included for comparison (Figure 1) with slight modifications to suit the DNA sequence of pHBV3.8. The oligo sequences were: 5’-AATCAGACAACTACTGTGGTTCAAGA GACCACAGTAGTTGTCTGATTTTTTTT-3’ (sense) and 5’-AGCTAAAAAAAATCAGACAACTACTGTGGTCTCTTGAACC ACAGTAGTTGTCTGATTGGCC-3’ (antisense) for pSi-core1; 5’-GGTCTTACATAAGAGCACTTTCAAGAGAAGTGCTCTT ATGTAAGACCTTTTTT-3’ (sense) and 5’-AGCTAAAAAAG GTCTTACATAAGAGCACTTCTCTTGAAAGTGCTCTTATGTA AGACCGGCC-3’ (antisense) for pSi-X.

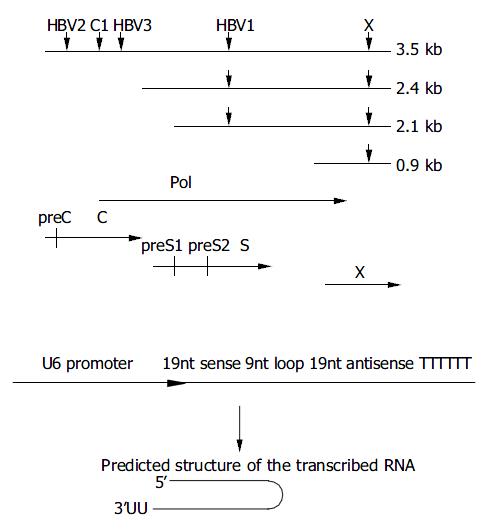

Figure 1 Design of siRNAs specific for HBV genome.

A: Down-ward arrows show the target sites within the RNA transcripts. The HBV ORFs are shown below aligned with HBV mRNA. B: Schematic presentation of U6 promoter constructs. The in-verted 19 nt sequences are separated by a 9 nt loop, transcrip-tion ends with 5Ts. The resulting shRNA (short hairpin RNA) are predicted to fold back to form a hairpin RNA.

pSi-EGFP-h was a control vector with insertion sequence targeting on EGFP gene. The synthesized oligos were: 5’-GACGTAAACGGCCACAAGTTTCAAGAGAACTTGTGG CCGTTTACGTCTTTTTT-3’ (sense) and5’-AGCTAAAAAAG ACGTAAACGGCCACAAGTTCTCTTGAAACTTGTGGCCGTT TACGTCGGCC-3’ (antisense).

Plasmid constructs

The oligos were annealed and cloned into ApaI-HindIII sites of pSilencer as described in the pSilencer 1.0 U6 manual (Ambion). All the plasmids constructed were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Quantitiation of HBsAg and HBeAg

The HBsAg and HBeAg secreted into the culture media were measured by diagnostic ELISA kit (Shanghai SIIC Kehua Biotech).

Northern blot analysis of viral RNA

Total RNA was extracted directly from transfected cells using TRIzol reagent (Gibco BRL). After 30 min of DNaseI digestion of remaining DNA, total RNA was re-extracted by TRIzol, precipitated and dissolved in DEPC-H2O. Ten micrograms of total RNA was electrophoresed on 10 g/L formaldehyde-agarose gel and then transferred to nylon membranes (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). After fixation at 120 °C for 30 min, the membrane was prehybridized for 6 h at 42 °C in 5×SSC, 5×Denhardt’s solution, 10 g/L SDS, 50 g/L formaldehyde, 0.1 mg/mL salmon sperm DNA ,followed by hybridization with full-length HBV DNA probes labeled with [α -32P] dCTP by hexamer random labeling kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) under the same condition of prehybridization at 42 °C for 16 h. After a stringent washing process at 68 °C, the signals were detected by autoradiography, then the blots were quantified by densitometry. The 28 s and 18 s rRNA were visualized under ultraviolet light for equal loading control. The values of HBV blots were normalized by monitoring the expression of an internal control CAT by CAT ELISA (Roche, Mannheim, Germany).

Quantitative real-time PCR

Huh-7 cells in 6-well plates were transfected with 2 µg of various plasmids. After 48 h of transfection, total RNA was extracted as described above. RNA was denatured for 5 min at 65 °C in the presence of random hexamer, immediately cooled in ice water, then reverse transcribed using SuperScript II reverse-transcriptase according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time PCR (iCycler, Bio-Rad) was performed as instructed by iCycler resource guide. Reactions with no reverse transcriptase enzyme added were performed in parallel. Briefly, reactions were carried out in 25 µL volume containing 2 µL of template (cDNA or RNA), 400 nmol/L of each forward and reverse primer and 1X SybrGreenI PCR Master Mix (Roche). To quantitate cellular transcripts, dilutions of plasmids containing the human GAPDH gene were run in parallel. The experiment was performed twice. The primer sequences used included: 5’-GGTATCGTGGAAGG ACTCATGAC3’ (sense) and 5’-ATGCCAGTGAGCTTCCCGT TCAGC 3’ (antisense) for GAPDH; 5’-GCTACACACCGTGACG GATATGG 3’ (sense) and 5’-CGAGCTGGATTGGAAAGCCC3’ (antisense) for MxA; 5’-TCAGAAGAGAAGCCAACGTGA-3’ (sense) and 5’-CGGAGACAGCGAGGGTAAAT-3’ (antisense) for 2’-5’OAS.

RESULTS

Inhibition of HBV gene expression in transiently transfected Huh-7 cells by RNAi

pSilencer, pSi-EGFP-h and other derivatives targeting on different regions of HBV genome were co-transfected with pHBV3.8 in the ratio of 10:1 into Huh-7 cells. pcDNA-CAT was also transfected as internal control. The secreted viral antigens, HBsAg and HBeAg in the culture media were quantified 48 h and 72 h after transfection. Transfection efficiencies were standardized by measurement of CAT using CAT ELISA Kit. Compared with control vector, HBsAg and HBeAg expressions were reduced by about 60% in average when measured 48 h after transfection (Figure 2). When the antiviral effect of siRNA was assessed 72 h post-transfection, the silencing effect was still apparent, indicating the stability of the transcribed RNAi. Among all the siRNAs used, pSi-HBV1 targeting on S gene as well as P gene of HBV genome was most potent, as HBsAg and HBeAg were reduced 86% and 83% 72 h after transfection, respectively.

Figure 2 Effect of RNAi on HBV protein expression in tran-siently transfected Huh-7 cells.

Reduction of HBV viral transcripts by RNAi

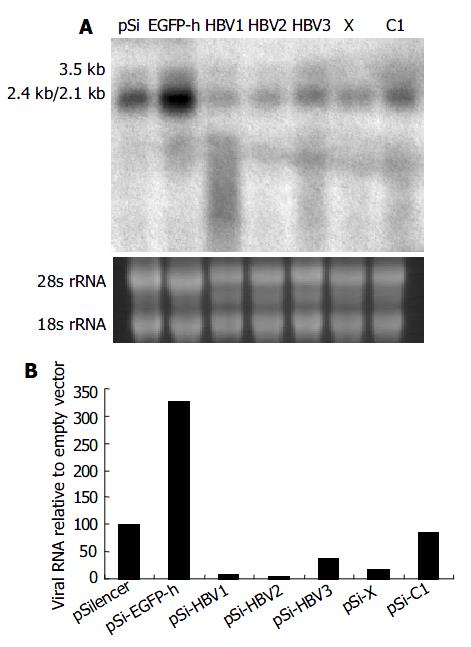

To determine whether viral pregenomic RNA and other transcripts were efficiently degraded by siRNA, Northern blot assay was carried out using 32P-labeled full length HBV fragment as the probe generated with a random-primed labeling kit. Compared with control vector pSi-EGFP-h, significant reduction of all the viral transcripts was observed when pSilencer vectors targeting on specific HBV RNA were used (Figure 3). Among them, pSi-HBV1 and pSi-HBV2 were much more efficient with over 90% reduction in viral RNAs.

Figure 3 Effect of RNAi on HBV gene transcription detected by Northern blot.

A: Northern blot experiment of HBV transcripts. The 28 s and 18s rRNAs were visualized under ultraviolet light for equal loading control. B: The hybridiza-tion signal was quantitatively evaluated by SmartviewTM im-age analysis software (Shanghai Fu-ri Inc).

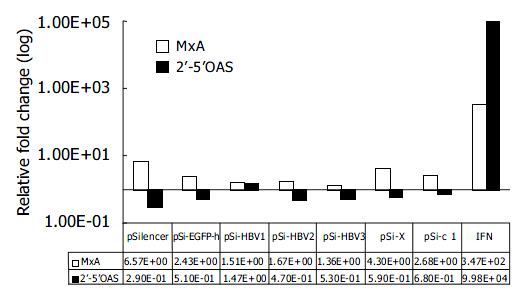

Vector-based siRNA could not activate interferon response

To rule out the possibility that inhibition of HBV gene expression and replication by vector-based siRNA was due to the dsRNA-induced activation of IFN pathway, we compared the mRNA levels of IFN-induced genes 2’-5’OAS and MxA by quantitative real-time PCR 48 h after transfection of siRNA generating plasmids. Compared with mock-transfected Huh-7 cells, IFN induced about 10 000 and 100-fold increase in 2’-5’OAS and MxA mRNA levels, respectively. While the transfection of pSi-HBV plasmids only led to 1.67-fold and 0.71-fold (in average) induction of MxA and 2’-5’OAS, respectively, thus eliminating the non-specific effect of siRNAs (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Effect of RNAi on IFN-induced genes.

Real-time PCR quantification of MxA and 2’-5’ OAS. The copy number of MxA and 2’-5’OAS were normalized with GAPDH. The rela-tive fold induction of each gene compared with mock trans-fection is shown.

DISCUSSION

Numerous reports have demonstrated that RNAi can block replication of various types of mammalian viruses, including two retroviruses, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)[7,15-17] and Rous sarcoma virus[18]; a negative-strand RNA virus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)[19], two positive-stranded RNA virus, hepatitis C virus (HCV)[9,20,21] and poliovirus[10]; and a DNA virus, human papillomavirus[22]. Although HBV is a DNA virus, its replication requires a key step of reverse transcription for synthesis of viral DNA from pregenomic RNA, which is quite different from other DNA viruses. Therefore, HBV is assumed to be susceptible to siRNA not only at the level of post-transcription, but also at the level of replication.

In this study, we demonstrated that vector-based siRNA could significantly inhibit HBV antigen expression (both HBsAg and HBeAg) in hepatocytes. Furthermore, Northern blot analysis revealed that HBV pregenomic RNA and other shorter transcripts were diminished in the presence of specific siRNAs. Our results were different from a previous report[14], which demonstrated that pSuper-core1 and pSuper-core2 did not inhibit HBsAg and resulted in only a minor reduction of about 13% in the 3.5-kb transcript whereas pSuper-X reduced both HBsAg and HBcAg, and resulted in a significant reduction of about 68% at the level of all the viral transcripts. However, they were consistent with McCaffrey et al[23] that siRNA targeting on the pregenomic RNA in the overlap region of the C and P open reading frames (ORF) reduced the levels of 2.4- and 2.1-kb RNAs and serum HBsAg even though it did not directly target on these RNAs. It can be assumed that HBV-specific siRNA first recognizes and degrades the corresponding sequence of viral pregenomic RNA, consequently depleting template for reverse transcription. Decreased synthesis of viral DNA then further influences the life cycle of HBV genome, especially in transcription and translation, thereby resulting in the overall inhibition of viral RNA and proteins.

Among the selected siRNAs, si-HBV1 is the most potent in inhibiting HBV replication. As si-HBV1 targeted on S region of the virus, multiple viral RNAs would be inhibited. Besides, it could also down-regulate the expression of P gene (the S ORF is within the P ORF), thus inhibiting viral replication in trans. These factors might explain, at least in part, why si-HBV1 has the highest efficacy.

Compared with the general nonspecific shutdown of cellular protein synthesis by double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) mediated primarily by IFN-α /β through the induction of protein kinase R (PKR) and RNaseL, the main known advantage of RNAi strategies is its high specificity on gene silencing. Attention has been paid to the potential non-specific effects of RNAi recently. Bridge et al[24] found that a substantial number of siRNA vectors could trigger an interferon response. Sledz et al[25] reported that transfection of siRNA resulted in interferon mediated activation of the Jak-Stat pathway and global up-regulation of IFN-stimulated genes. Although Kapadia et al[20] and we did not detect the activation of known IFN-inducible pathways after transfection of siRNA or siRNA generating plasmids, the overall inhibition of viral RNAs by RNAi in our study and others still raise the possibility that RNAi may have some sequence-independent antiviral effects at certain doses. Overdose of siRNA or accumulation of unprocessed or aberrantly processed Pol III transcripts may trigger interferon response. Hence, further studies are required to optimize the dose and structure of short-haipin RNA as well as the delivery strategy to minimize the non-specific effects.

Taken together, our data show that RNAi is an attractive new strategy to inhibit the replication of hepatitis B virus. But to really apply this phenomenon to medical therapy, many problems are yet to be solved. One major problem is the selection of target sequence. Although there have been some online tools to help select the target sequence, the result is not always satisfactory. Recently, a theory has been proposed that siRNAs with relative stability at the 5’ end of the sense strand, relative instability at the 5’ end of the antisense strand and the cleavage site will most probably be the most effective ones[26-28]. These findings have significantly enlarged our knowledge of target selection, but the best siRNA should still be selected empirically. Therefore, a simple method of finding out the best target is urgently needed. Another major problem is how to efficiently and specifically deliver the siRNA-expressing vectors to the target cell types[29]. At present, retroviral or lentiviral vectors containing RNAi cassettes seem to be a good delivery system in carrying out gene silencing in vivo[30,31]. Chemically modified synthetic siRNA, which could be delivered into cells without cationic lipid carrier also holds promise for a future therapeutic agent[8]. With the advance in newly established techniques, RNAi may provide an effective therapeutic solution for HBV infection in the near future.