Published online Sep 1, 2004. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i17.2605

Revised: April 4, 2004

Accepted: April 14, 2004

Published online: September 1, 2004

Chronic mesenteric ischemia is an uncommon condition associated with a high morbidity and mortality. We reported a 36-year old women with postprandial abdominal pain due to chronic mesenteric ischemia caused by a fistula between superior mesenteric and common hepatic artery.

- Citation: Kayacetin E, Karaköse S, Karabacakoglu A, Emlik D. Mesenteric Ischemia: An unusual presentation of fistula between superior mesenteric artery and common hepatic artery. World J Gastroenterol 2004; 10(17): 2605-2606

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v10/i17/2605.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v10.i17.2605

Chronic mesenteric ischemia (CMI) is an uncommon condition associated with a high morbidity and mortality and the symptoms may be nonspecific until late in the course of disease[1,2].

The most common cause of CMI is atherosclerosis. Involvement of the celiac, superior mesenteric, and inferior mesenteric arteries at their origins is typical[3]. We reported an abnormal communication between the superior mesenteric artery (SMI) and common hepatic artery (CHA) which caused splanchnic hypoperfusion. To our knowledge, this entity has not been reported previously in the literature.

The patient was a 36-year old woman who had complained of severe postprandial abdominal pain and abdominal distention for 9 mo. The pain was described as a severe, poorly localized one radiating to the back. No fever, nause or vomiting, hematochezia, or weight change was reported. She had no history of previous trauma, abdominal surgery, hepatic or pancreatic disease. Hematological and biochemical test results on admission were as follows: white blood cell count, 7000/mm3 (normal, 4.0-10.0) ; hemoglobin, 13.4 g/dL (normal, 12.1-17.2) ; platelets, 177 103/uL (normal, 150-400) ; total bilirubin, 0.36 mg/dL (normal, 0.1-1.3) ; albumin, 4.6 g/dL (normal, 3.5-5.2) ; aspartate aminotransferase, 29 u/L (normal, 10-31) ; alanine aminotransferase, 30 u/L (normal, 10-31) ; amylase, 74 u/L (normal, 0-90) ; lactate dehydrogenase, 335 u/L (normal, 220-450).

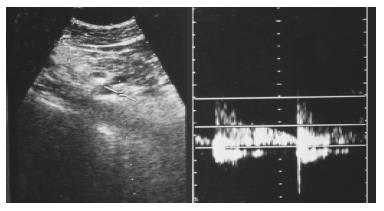

On physical examination, pulse rate was 84/min and arterial blood pressure was 110/70 mm Hg. Rectal examination revealed no mass and the stool was hemoccult negative. Computerized tomography of the abdomen, plain abdominal radiography and upper endoscopy were normal. Abdominal ultrasonography showed a slightly enlarged liver with normal echo pattern and communication between the common hepatic artery and superior mesenteric artery (Figure 1). On Doppler ultrasound, arterial flow was observed within this fistula (Figure 2). We suspected CMI and consequently performed anjiography. Celiac arteriogram revealed an abnormal fistula from the SMA to the CHA and not any other arterial communications (Figure 3).

A small quantity diet with low fat content was adviced to the patient who responded well to this measure and after one month she was free of abdominal pain, and also of abdominal distension, hence we did not plan to perform surgery or interventional radiology.

The major vascular supply of the bowel depends on the celiac, superior mesenteric and inferior mesenteric arteries. The superior mesenteric artery is the largest of all the aortic branches and carries over 10% of the cardiac output. Splanchnic circulation was about 30% of the circulating blood volume[4,5].

CMI is a disputatious diagnostic problem. Most patients do not develop ischemic symptoms because of the abundant collateral circulation of these intestines. Usually at least two of the three mesenteric arteries must be significantly stenotic before symptoms developed[6,7].

Clasically, postprandial abdominal pain, known as “intestinal angina”, was almost invariably the principal symptom. Other less consistent symptoms included bloating, flatulance, nause, and variable changes in bowel habit[2,8,9]. Superior mesenteric artery blood flow increased after ingestion of meals with a high fat content[5]. Our patient reported significant crampy abdominal pain after heavy meal, meanwhile consuming small and low fat meal did not cause pain. The pathophysiological mechanism in this case was an arterial abnormality which was an abnormal communication between SMI and CHA. Under such a condition blood perfusion became impaired. A higher blood pressure in SMA could force flow towards CHA. Blood flow might be sufficient to sustain resting metabolic needs, but after a heavy meal, however, splanchnic blood flow did not increase because of this steal phenomenon.

A diagnosis of vasculogenic mesenteric ischemia was made on the basis of the clinical history and dupplex ultrasonography findings. Other causes of abdominal pain were excluded. Large majority of cases of colonic ischemia were due to non-occlusive diseases[10]. Other less common causes of CMI were vasculitis, SLE, sick cell disease, hypercoagulable states, medications (estrojen, danazol, vazopressin, gold, psychotropic drugs), and cocaine abuse[1,11].

Clinical presentations of the patient might depend on the size and amount of blood flow through the fistula, ranging from asymptomatic cases to overt intestinal ischemia.

We suggested nutritional measures aiming at avoiding large meals and reduction of long-chain fat content.

In a patient with an unexplaniable chronic abdominal pain, after exclusion of common reasons, vascular abnormalities must be suspected. Like in our case, there might be other abnormal vascular communications, thus even in a young patient vascular examinations might be necessary.

Edited by Wang XL and Chen WW Proofread by Xu FM

| 1. | Rogers DM, Thompson JE, Garrett WV, Talkington CM, Patman RD. Mesenteric vascular problems. A 26-year experience. Ann Surg. 1982;195:554-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Croft RJ, Menon GP, Marston A. Does 'intestinal angina' exist A critical study of obstructed visceral arteries. Br J Surg. 1981;68:316-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kazmers A. Operative management of chronic mesenteric ischemia. Ann Vasc Surg. 1998;12:299-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Muller AF. Role of duplex Doppler ultrasound in the assessment of patients with postprandial abdominal pain. Gut. 1992;33:460-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sidery MB, Macdonald IA, Blackshaw PE. Superior mesenteric artery blood flow and gastric emptying in humans and the differential effects of high fat and high carbohydrate meals. Gut. 1994;35:186-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Thomas JH, Blake K, Pierce GE, Hermreck AS, Seigel E. The clinical course of asymptomatic mesenteric arterial stenosis. J Vasc Surg. 1998;27:840-844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kolkman JJ, Groeneveld AB. Occlusive and non-occlusive gastrointestinal ischaemia: a clinical review with special emphasis on the diagnostic value of tonometry. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1998;225:3-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bower TC. Ischemic colitis. Surg Clin North Am. 1993;73:1037-1053. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Zelenock GB, Graham LM, Whitehouse WM, Erlandson EE, Kraft RO, Lindenauer SM, Stanley JC. Splanchnic arteriosclerotic disease and intestinal angina. Arch Surg. 1980;115:497-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Marston A, Clarke JM, Garcia Garcia J, Miller AL. Intestinal function and intestinal blood supply: a 20 year surgical study. Gut. 1985;26:656-666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Patel A, Kaleya RN, Sammartano RJ. Pathophysiology of mesenteric ischemia. Surg Clin North Am. 1992;72:31-41. [PubMed] |