Published online Aug 15, 2004. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i16.2444

Revised: December 26, 2003

Accepted: February 1, 2004

Published online: August 15, 2004

AIM: To evaluate the role of miniprobe ultrasonography under colonoscope in the diagnosis of submucosal tumor of the large intestine, and to determine its imaging characteristics.

METHODS: Thirty-five patients with submucosal tumors of the large intestine underwent miniprobe ultrasonography under colonoscope. The diagnostic results of miniprobe ultrasonography were compared with pathological findings of specimens by biopsy and surgical resection.

RESULTS: Lipomas were visualized as hyperechoic homogeneous masses located in the submucosa with a distinct border. Leiomyomas were visualized as hypoechoic homogeneous mass originated from the muscularis propria. Leiomyosarcomas were shown with inhomogeneous echo and irregular border. Carcinoids were presented as submucosal hypoechoic masses with homogenous echo and distinct border. Lymphangiomas were shown as submocosal hypoechoic masses with cystic septal structures. Malignant lymphomas displayed as hypoechoic masses from mucosa to muscularis propria, while pneumatosis cystoids intestinalis originated from submucosa with a special sonic shadow. One large leiomyoma was misdiagnosed as leiomyosarcoma.

CONCLUSION: Endoscopic miniprobe ultrasonography can provide precise information about the size, layer of origin, border of submucosal tumor of the large intestine and has a high accuracy in the diagnosis of submucosal tumor of the large intestine. Pre-operative miniprobe ultrasonography under colonoscope may play an important role in the choice of therapy for submucosal tumor of the large intestine.

- Citation: Zhou PH, Yao LQ, Zhong YS, He GJ, Xu MD, Qin XY. Role of endoscopic miniprobe ultrasonography in diagnosis of submucosal tumor of large intestine. World J Gastroenterol 2004; 10(16): 2444-2446

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v10/i16/2444.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v10.i16.2444

Due to the development of colonoscope and CT, the reported number of submucosal tumor (SMT) of the large intestine has been increased. SMT of the large intestine includes lipoma, lymphangioma, leiomyoma, carcinoid, metastatic tumor, etc. Previous diagnosis depended mainly on barium enema and colonoscope, but none of them could make clear the histological features of SMT, and it was also difficult to differentiate SMT from extramural compression. In the 1980 s, the development of endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) significantly improved the accuracy of diagnosis of the digestive tract diseases[1]. EUS can provide detailed information about gastrointestinal wall structure and adjacent organs. EUS is highly accurate in the visualization of submucosal lesions and their sonographic layer of origin within gastrointestinal wall. Concerning SMT of the digestive tract, several studies have been published mainly in upper digestive tract[2-4], but there have been few studies on SMT of the lower digestive tract. The aim of this study was to assess the value of EUS in the diagnosis of SMT of the large intestine and determine their imaging characteristics.

EUS was performed in 35 patients with elevated lesions which had normal mucosal vision under colonoscope between January 2001 and November 2003. The patient group comprised 19 men and 16 women with a mean age of 54.6 years (range, 32-72 years). The diameter of lesions ranged 0.5-4.2 cm. Of the 35 lesions, 28 were confirmed histologically by endoscopic biopsy and surgical resection, and the histological findings were compared with ultrasonographic imagings. The other 7 patients were observed without resection. The lesion that caused extramural compression of intestinal wall was excluded from this study, which could easily be confused with SMT clinically.

A ultrasonic miniprobe (Olympus UM-2R, 12MHz; UM-3R, 20 MHz, Tokyo, Japan) was introduced under electronic colonoscope (Olympus CF-Q240, Tokyo, Japan), as well as an endoscopic ultrasonography system (Olympus EU-M30, Tokyo, Japan). The video image was recorded by ultrasonography image recorder (Sony UP-890, Tokyo, Japan).

Patients undergoing EUS were prepared with the same method as for conventional colonoscopy. Five mg midazolam was administered intramuscularly and 10 mg scopolamine butylbromide was injected intravenously for sedation before the procedure. When an elevated lesion with normal mucosa was observed endoscopically, the tip of the colonoscope was placed at the distal end of the lesion. The lumen was filled with 100-200 mL water to achieve acoustic coupling between the transducer and the intestinal wall. Subsequently, the miniprobe was introduced through the working channel of the colonoscope and advanced beyond the lesion. The lesion was assessed by real-time ultrasonography while the miniprobe was moved over the lesion region[4].

The layer of origin of SMT was determined according to the continuity between the lesion and adjacent normal colonic wall. The nature of SMT was assessed by its size, layer of origin, border characteristic and internal echogenicity.

Values were presented as mean±SD. Analysis of variance with t test was used for statistical analysis. P < / = 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

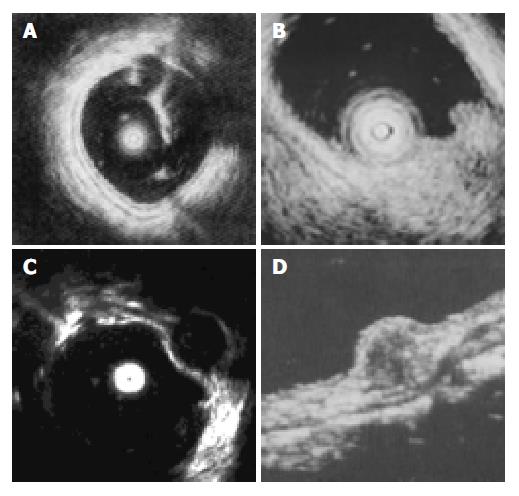

EUS was performed successfully in all 35 patients. The normal wall of the large intestine was displayed in 5 layers (Figure 1). The first 2 layers represented the mucosa (m). The third layer stood for the submucosa (sm). The muscularis propria (mp) was depicted by the 4th layer. Adventitia or serosa (sa) was sometimes displayed as the 5th layer. As the lower part of rectum below the peritoneal reflection had no serosa, the pericolic fat and the mural outer layer constituted the hyperechoic layer. SMT was mostly visualized as hyperechoic, hypoechoic, anechoic lesions within the colorectal wall (Figure 1). The EUS characteristics of SMT are summarized in Table 1.

| Diagnosis (No.of patients) | EUS findings | |||||

| Size (mm) | Shape | Border | Layer of origin | Echogenicity | Internal echo | |

| Lipoma (n = 12) | 15 ± 3.1 | Round | Regular | Third | Hyperechoic | Homogeneous |

| Leiomyoma (n = 8) | 17 ± 4.3 | Round | Regular | Fourth | Hypoechoic | Homogeneous |

| Lymphangioma (n = 6) | 14 ± 2.3 | Round | Regular | Third | Anechoic | Multilocular |

| Leiomyosarcoma (n = 2) | 38 ± 2.8 | Round Lobulated | Regular | Fourth | Hypoechoic | Inhomogeneous |

| Carcinoid (n = 3) | 14 ± 4.2 | Round | Regular | Third | Hypoechoic | Homogeneous |

| Malignant lymphoma (n = 2) | Irregular | Irregular | Second to fourth | Hypoechoic | Inhomogeneous | |

| Pneumatosis cystoid intestinalis (n = 2) | 17 ± 3.6 | Irregular | Irregular | Third | Hypoechoic | Inhomogeneous |

Lipomas, the most common SMT of the large intestine (accounting for 1/3 in our study), were visualized as hyperechoic homogeneous masses located in the third layer (sm) with a distinct border. Leiomyomas were visualized as hypoechoic homogeneous mass originated from the 4th layer(mp). Two leiomyosarcomas with a mean diameter of 38 mm, inhomogeneous and irregular border were confirmed histologically by surgical resection. One large leiomyoma was misdiagnosed as leiomyosarcoma. Carcinoid was presented as a submucosal hypoechoic mass with a homogenous echo and distinct border. All 3 carcinoids were located in rectus, of which 2 were less than 10 mm in diameter, submucosal continuity was not disrupted, and were resected under colonoscope. Another one was resected by surgery because of large diameter (1.8 cm) and disrupted submucosal continuity. Lymphangiomas were shown with EUS as submucosal anechoic masses with cystic septal structures. Malignant lymphoma displayed as hypoechoic mass from mucosa to mp depending on stage of the disease, while pneumatosis cystoids intestinalis, not real tumor, originated from sm with a special sonic shadow behind mass.

Barium enema and colonoscopy are the main widely used examinations in the diagnosis of submucosal lesions of the large intestine. Takada et al[3] classified colonic SMT into five types on the basis of barium enema studies. Typical endoscopic feature of the colonic SMT is an elevated lesion with normal mucosa, and each has its own endoscopic morphologic features. However, it is difficult to determine the real size, layer of the origin and histologic nature of SMT with these procedures alone. In addition, lesions smaller than 10 mm cannot be detected.

Under these circumstances, the development of EUS has provided a brand new dimension in the diagnosis of colorectal lesions[5-11]. EUS can image the entire structure of the colonic wall which corresponds to the histologic layer structure. Normal colonic wall is presented as five-layered structure. By placing high frequency miniprobe on the elevated spot, the layer of the origin of SMT is generally determined by demonstrating continuity between the tumor and the colonic wall. Extraluminal compression is easily differentiated from SMT by EUS. Our study found lipoma, lymphangioma and carcinoid were originated from the third layer (sm). Myogenic tumors were found to be originated from the fourth layer (mp). According to literature, some myogenic tumors were from muscularis mucosa[12].

The size of SMT can be measured with EUS. The biggest SMT we detected in this study was 4.2 cm in diameter. Because of the high frequency employed in this study, it was difficult for miniprobe to observe big lesions. In general, the lower the frequency employed, the better the depth of US penetration and the clearer the image. Therefore, 20 MHz is suitable for clear images of superficial lesions. On the other hand, 12 MHz and 7.5 MHz are more suitable for the evaluation of the big lesions and contiguous tissues. The smallest SMT we detected was 5 mm in diameter, while Sun et al[13] reported that the smallest size detectable was 2 mm in diameter histologically.

The nature of SMT can be determined by the internal echogenicity. In this study, all lipomas were hyperechoic homogeneous and lymphangiomas were anechoic with cystic septal structures[14]. The other SMTs were mostly visualized as hypoechoic masses. Therefore, the former findings are strongly suggestive of lipomas and lymphangiomas.

Leiomyosarcoma of the large intestine is extremely rare, only accounting for 0.1% of colonic malignancy[12]. With regard to differential diagnosis of leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas, it is suggested to distinguish according to the size and the internal ultrasonsic characteristics of the tumor in literature. For the lesion which has the diameter < 30 mm, homogenous resonance and clear borderline, the benign is considered. In contrast, if the lesion has a diameter > 30 mm, inhomogeneous resonance and irregular border, it may be diagnosed as malignant. But one case in our study with a diameter of 3.2 cm was eventually diagnosed as leiomyoma by pathology. Endoscopic ultrasonography guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) can further help to diagnose the submucosal masses[15].

EUS is useful in determining the therapy for SMT of the large intestine[16]. Lipoma and lymphangioma are easy to be diagnosed by EUS, and these lesions can be removed endoscopically or observed without resection. Although leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma are difficult to differentiate, leiomyosarcoma should be strongly suspected, and surgery should be considered when the tumor is over 30 mm in diameter and has an inhomogeneous internal echo. Although myogenic tumor diagnosed by EUS is an indication for surgery at our department, patients are followed up by EUS according to a strict protocol when the size of tumor is smaller than 20 mm and the patient declines surgery.

In conclusion, EUS can provide precise information about the size, layer of origin, and echogenicity of the SMT of the large intestine. It is useful in the diagnosis of SMT of the large intestine and can have an important role in the choice of therapy.

We thank Eisai Cho and Kenjiro Yasuda of the Department of Gastroenterology of Kyoto Second Red Cross Hospital (Japan) for their technical support to this study.

Edited by Kumar M and Zhu LH Proofread by Xu FM and Chen WW

| 1. | Stergiou N, Haji-Kermani N, Schneider C, Menke D, Köckerling F, Wehrmann T. Staging of colonic neoplasms by colonoscopic miniprobe ultrasonography. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2003;18:445-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Waxman I, Saitoh Y, Raju GS, Watari J, Yokota K, Reeves AL, Kohgo Y. High-frequency probe EUS-assisted endoscopic mucosal resection: a therapeutic strategy for submucosal tumors of the GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:44-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Takada N, Higashino M, Osugi H, Tokuhara T, Kinoshita H. Utility of endoscopic ultrasonography in assessing the indications for endoscopic surgery of submucosal esophageal tumors. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:228-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Xi WD, Zhao C, Ren GS. Endoscopic ultrasonography in preoperative staging of gastric cancer: determination of tumor invasion depth, nodal involvement and surgical resectability. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:254-257. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Roseau G, Dumontier I, Palazzo L, Chapron C, Dousset B, Chaussade S, Dubuisson JB, Couturier D. Rectosigmoid endometriosis: endoscopic ultrasound features and clinical implications. Endoscopy. 2000;32:525-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Shimizu S, Myojo S, Nagashima M, Okuyama Y, Sugeta N, Sakamoto S, Kutsumi H, Otsuka H, Suyama Y, Fujimoto S. A patient with rectal cancer associated with ulcerative colitis in whom endoscopic ultrasonography was useful for diagnosis. J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:516-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gast P, Belaïche J. Rectal endosonography in inflammatory bowel disease: differential diagnosis and prediction of remission. Endoscopy. 1999;31:158-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lew RJ, Ginsberg GG. The role of endoscopic ultrasound in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2002;12:561-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Polkowski M, Regula J, Wronska E, Pachlewski J, Rupinski M, Butruk E. Endoscopic ultrasonography for prediction of postpolypectomy bleeding in patients with large nonpedunculated rectosigmoid adenomas. Endoscopy. 2003;35:343-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bhutani MS, Nadella P. Utility of an upper echoendoscope for endoscopic ultrasonography of malignant and benign conditions of the sigmoid/left colon and the rectum. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3318-3322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mo LR, Tseng LJ, Jao YT, Lin RC, Wey KC, Wang CH. Balloon sheath miniprobe compared to conventional EUS in the staging of colorectal cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:980-983. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Xu GQ, Zhang BL, Li YM, Chen LH, Ji F, Chen WX, Cai SP. Diagnostic value of endoscopic ultrasonography for gastrointestinal leiomyoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2088-2091. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Sun S, Wang M, Sun S. Use of endoscopic ultrasound-guided injection in endoscopic resection of solid submucosal tumors. Endoscopy. 2002;34:82-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Watanabe F, Honda S, Kubota H, Higuchi R, Sugimoto K, Iwasaki H, Yoshino G, Kanamaru H, Hanai H, Yoshii S. Preoperative diagnosis of ileal lipoma by endoscopic ultrasonography probe. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;31:245-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kinoshita K, Isozaki K, Tsutsui S, Kitamura S, Hiraoka S, Watabe K, Nakahara M, Nagasawa Y, Kiyohara T, Miyazaki Y. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy in follow-up patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:1189-1193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ouchi J, Araki Y, Chijiiwa Y, Kubo H, Hamada S, Ochiai T, Harada N, Nawata H. Endosonographic probe-guided endoscopic removal of colonic pedunculated leiomyoma. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2000;63:314-316. [PubMed] |