Copyright

©The Author(s) 2015.

World J Gastroenterol. Oct 28, 2015; 21(40): 11321-11330

Published online Oct 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i40.11321

Published online Oct 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i40.11321

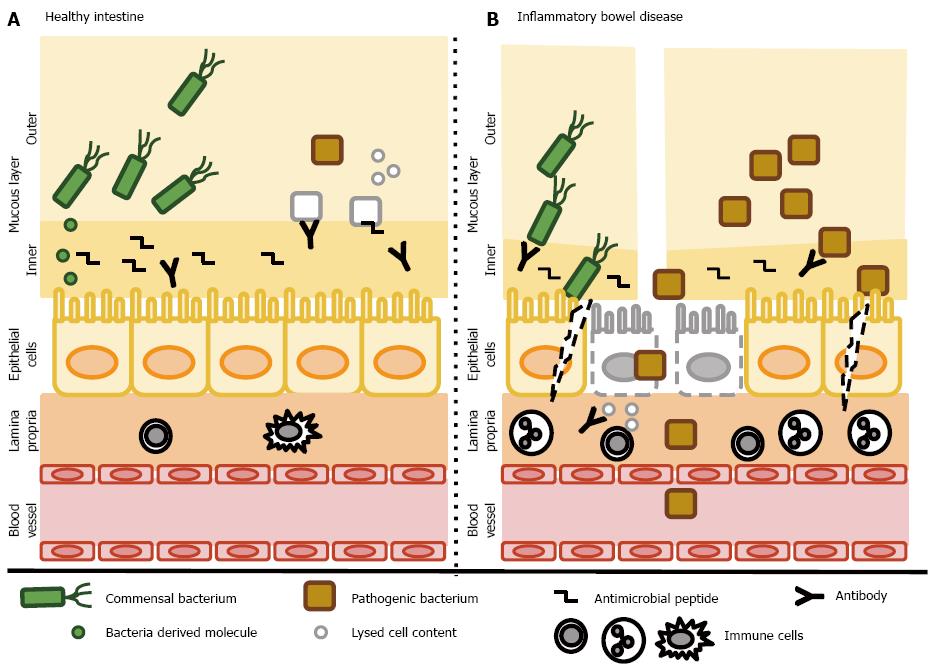

Figure 1 Host-bacteria interactions.

A: In the healthy gut, both commensal and pathogenic bacteria reside in the outer layer of the intestinal mucous layer without coming into direct contact with epithelial cells. The inner layer contains abundant antibacterial peptides and secreted antibodies that prevent the invasion of bacteria. Pathogenic bacteria are eradicated by various mechanisms. Commensal bacteria secrete various molecules that help to maintain the intestinal barrier, activate cell survival pathways and suppress inflammatory responses. Epithelial cells form a continuous, selectively permeable layer connected by intercellular junctions. The lamina propria contains only a few resident immune cells; B: In inflammatory bowel disease, the mucous layer is reduced and contains fewer antimicrobial peptides and secretory antibodies. The abundance of commensal bacteria is reduced in favor of pathogenic bacteria and both types enter the inner mucosal barrier and interact directly with epithelial cells. Some epithelial cells undergo cell death and disruption of the epithelial barrier occurs. Cell components are released and trigger further inflammation. Disruption of the epithelial barrier enables bacteria to invade the submucosa and recruit inflammatory cells. Finally, chronic inflammation develops. A dysbalanced immune system leads to the production of antibodies recognizing both commensal bacteria (and further reduce their numbers) and cells of the host, leading to further tissue destruction and inflammation, creating the “circulus vitiosus” typical for inflammatory bowel diseases.

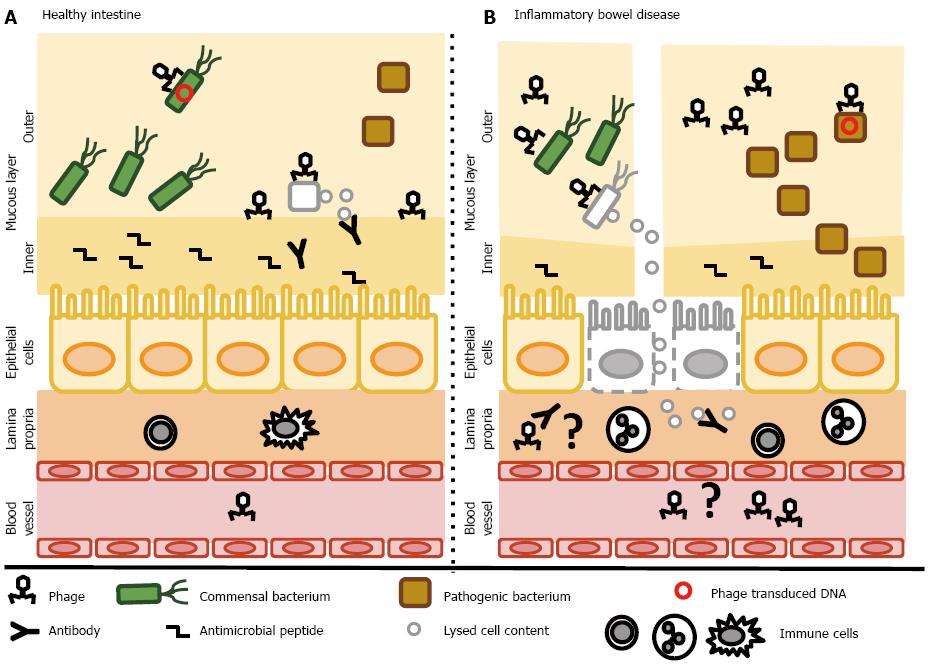

Figure 2 Putative contribution of bacteriophages to regulation of the intestinal bacteria - a simplified scheme.

A: In the healthy gut, bacteriophages might increase the fitness of commensal bacteria by the delivery of genes with environmental benefit or contribute to reduction of the pathogenic bacteria. Moreover, phages directly interact with the glycoproteins of the mucous layer and provide protection against invading bacteria. In some healthy individuals, phages have been detected in the circulation, suggesting the possibility that they cross the intestinal epithelial barrier; B: In inflammatory bowel disease, more phages are found in the mucous layer. Higher numbers of phages may be involved in reducing the amount of commensal bacteria, and may drive the transfer of genes with environmental benefit to pathogenic bacteria. Due to the reduced mucosal layer, phage interactions with mucosal glycoproteins may be reduced. Moreover, disruptions in the epithelial barrier might lead to the migration of many phage particles into the lamina propria or even the circulation. In the lamina propria, phages may serve as a local trigger of the immune response. After translocation to the systemic circulation, a systemic immune response might occur.

- Citation: Babickova J, Gardlik R. Pathological and therapeutic interactions between bacteriophages, microbes and the host in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(40): 11321-11330

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i40/11321.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i40.11321