Copyright

©2009 The WJG Press and Baishideng.

World J Gastroenterol. Jan 14, 2009; 15(2): 151-159

Published online Jan 14, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.151

Published online Jan 14, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.151

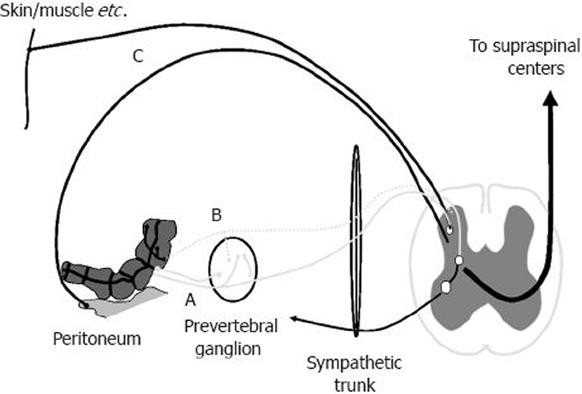

Figure 1 Afferent nerve supply of the gut.

True visceral afferents innervate the gut, and most run temporarily together with either the sympathetic or parasympathetic nerves to enter the spinal cord. During inflammation, silent afferents (dashed line) may become activated and contribute to the sensory response. The peritoneum and parietal serous membranes of the lungs and heart have their own parietal nerve supply, which is organized like that of the somatic structures.

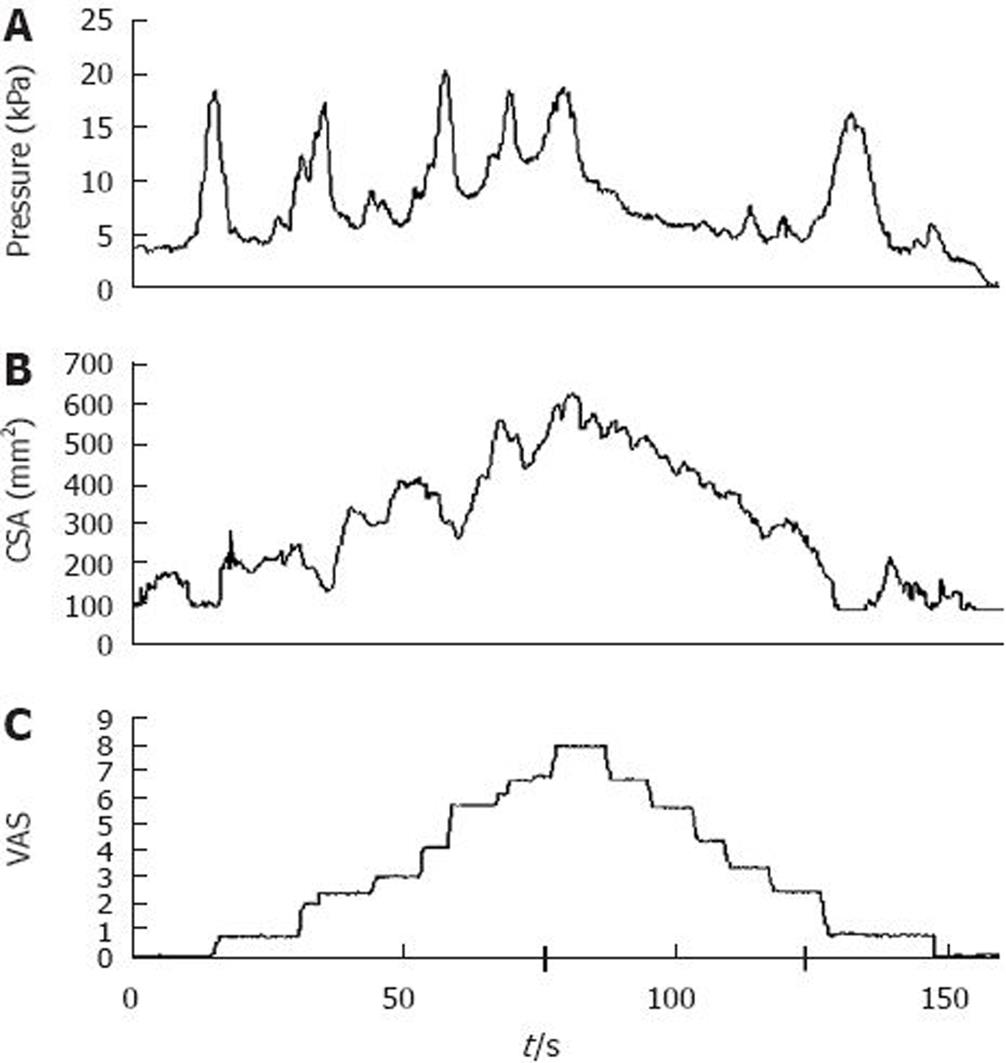

Figure 2 Illustration of mechanical stimulation in the esophagus.

The bag was filled at an infusion speed of 25 mL/min. During distension, (A) pressure, (B) cross-sectional area (CSA) and (C) pain intensity was recorded on line. The increase in CSA corresponded with increasing stimulus intensity after the bag was filled with water, whereas there was little relation between the pressure waves and the sensation. The pain intensity was rated on a visual analogue scale (VAS), with 5 as the pain threshold. An intensity of 8 on the VAS resulted in reversal of the pump. For details see Drewes et al[35].

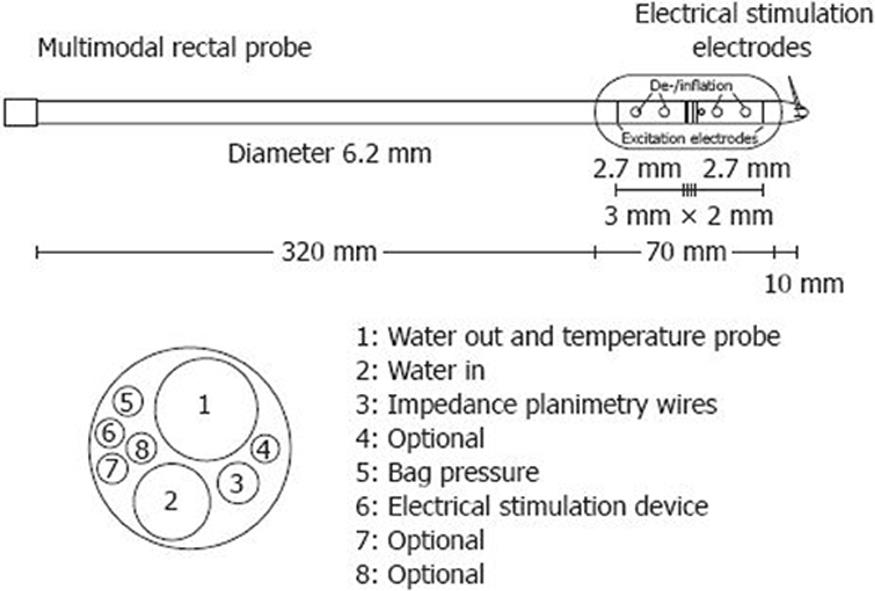

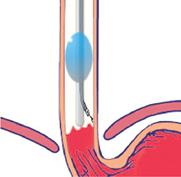

Figure 3 Probe used for measuring rectal CSA during distension.

Figure 4 An example of targeted colonic stimulation is shown, which demonstrates the electrode position.

The controlled position, which can be altered in case of stimulation in vicinity of somatic structures and nerves, is a major advantage.

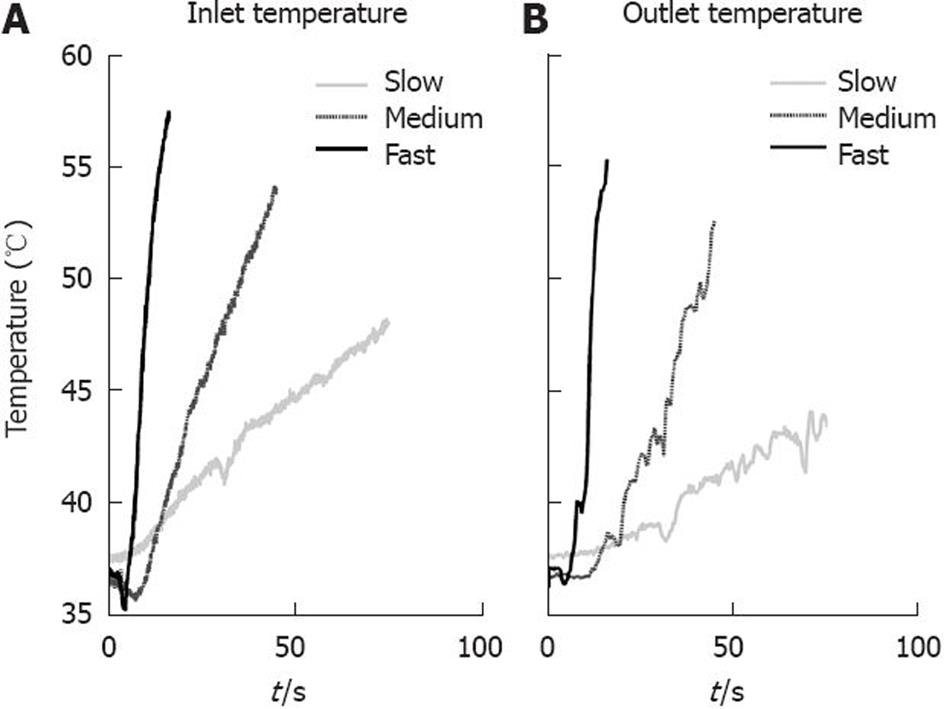

Figure 5 Temperature stimuli with three different incline rates.

A: Left graph shows the temperature measured at the inlet of the bag; B: Right graph shows the temperature measured at the outlet of the bag.

Figure 6 Newly de-veloped multimodal endoscopic probe that allows comprehensive sensory information combined with visual mucosal inspection and biopsy specimens.

- Citation: Brock C, Arendt-Nielsen L, Wilder-Smith O, Drewes AM. Sensory testing of the human gastrointestinal tract. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(2): 151-159

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i2/151.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.151