Published online Dec 18, 2016. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v7.i12.826

Peer-review started: June 27, 2016

First decision: August 11, 2016

Revised: August 22, 2016

Accepted: October 25, 2016

Article in press: October 27, 2016

Published online: December 18, 2016

To evaluate the effect of introducing a structured online follow-up system on the response rate.

Since June 2015 we have set up an electronic follow-up system for prosthesis in orthopedic patients. This system allows prospective data gathering using both online and paper questionnaires. In the past all patients received questionnaires on paper. This study includes only patients who received elbow arthroplasty. Response rates before and after introduction of the online database were compared. After the implementation, completeness of the questionnaires was compared between paper and digital versions. For both comparisons Fisher’s Exact tests were used.

A total of 233 patients were included in the study. With the introduction of this online follow-up system, the overall response rate increased from 49.8% to 91.6% (P < 0.01). The response rate of 92.0% in the paper group was comparable to 90.7% in the online group (P > 0.05). Paper questionnaires had a completeness of 54.4%, which was lower compared to the online questionnaires where we reached full completeness (P < 0.01). Furthermore, non-responders proved to be younger with a mean age of 52 years compared to a mean age 62 years of responders (P < 0.05).

The use of a structured online follow-up system increased the response rate. Moreover, online questionnaires are more complete than paper questionnaires.

Core tip: Since the last decade, increasing attention is paid on patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) and several online follow-up systems became available to collect PROMs. The purpose of this article was to evaluate the introduction of a structured online follow-up system in order to facilitate analysis of data.

- Citation: Viveen J, Prkic A, The B, Koenraadt KLM, Eygendaal D. Effect of introducing an online system on the follow-up of elbow arthroplasty. World J Orthop 2016; 7(12): 826-831

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v7/i12/826.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v7.i12.826

In 2002, the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Registry started using patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) on a national scale. In 2011, patients’ response rates of up to 90.2% were reported for this registry, Several other national registries have followed their model. In general, most PROMs data are collected from total hip replacement patients. None of the registries included mandatory PROMs on elbow arthroplasty in their dataset.

Nevertheless, PROMs are increasingly used to evaluate the outcome of surgical procedures in patient care and in clinical orthopaedic research projects[1-4]. These subjective outcomes may be even of more clinical importance than objective outcomes such as range of motion, since patient satisfaction is determined in a complex multifactorial way and does not always correlate well with easy-to-measure objective endpoints.

Unfortunately, in all medical fields researchers and clinicians have to deal with non-responders. This can potentially lead to biased results. And although statistical methods can be employed in an attempt to reduce this effect, it is better to achieve a high response rate to begin with. Therefore encouragement of patients to complete questionnaires is necessary, ideally by using simple and attractive tools.

Especially in patients who received elbow prostheses a structured follow-up is important, as the survival rate of elbow prosthesis is not as high as the rate of hip- and knee arthroplasties[3]. Despite of several technical improvements of the implants, complications still plague patients with a total elbow arthroplasty. Symptoms of a loosened elbow prosthesis are sometimes unclear and unspecific. This makes recognition at an early stage difficult. Nevertheless, it is essential to have the earliest detection as possible, since loosening of the prosthesis may cause irreversible bone destruction[5-8].

Since the last decade, several online follow-up systems became available to collect PROMs. Before these systems became available, all questionnaires were sent manual on paper. In the current study we want to report on the advantages and disadvantages of using an online follow-up system. The aim of this study is to evaluate the effect of introducing a structured online follow-up system, as our hypothesis was to increase the response rate in order to obtain a complete follow-up of patients who received elbow arthroplasty.

This study includes patients who have received surgery at our hospital for four types of elbow arthroplasties; total elbow prosthesis, radial head prosthesis, radiocapitellar prosthesis and revisions of aforementioned prosthesis. Patients were excluded if they were cognitive or physical impaired and therefore unable to complete questionnaires or to visit the outpatient clinic. In total 233 patients met the inclusion criteria and were included for the study.

Demographic data are presented in Table 1. Ninety-nine patients received a total elbow arthroplasty, 14 patients a radiocapitellar prosthesis, 68 patients a radial head prosthesis and 52 patients received revision surgery of aforementioned prosthesis. There were 60 men and 173 woman included. Mean age at surgery was 61 years (SD 13). For further details for each type of elbow arthroplasty see Table 1.

| Total elbow prosthesis | Radiocapitellar prosthesis | Radial head prosthesis | Revision surgery | Total | |

| Patients (n) | 99 | 14 | 68 | 52 | 233 |

| Sex | |||||

| Man | 22 | 7 | 19 | 12 | 60 |

| Woman | 77 | 7 | 49 | 40 | 173 |

| Age (yr) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 69 (4) | 56 (7) | 50 (13) | 61 (13) | 61 (13) |

Since June 2015 we have set up an electronic follow-up system (online PROMs, Interactive Studios, Rosmalen, The Netherlands), which allows prospective data gathering using online questionnaires. Online questionnaires are sent automatically at multiple follow-up moments after surgery or manual if patients prefer paper questionnaires. All questionnaires we use are valid in our language. Additional physical examination results can be added manually during reassessment at the outpatient clinic.

Until this introduction all patients received questionnaires on paper. Questionnaires were sent regarding the same follow-up moments, but monitoring was poor since no structured (online) system was available. Patients who received surgery before implementation of the online system are added to the system as well. Questionnaires sent after June 2015 for this group of patients counted as post implementation questionnaires.

When elbow arthroplasty surgery is planned at the outpatient clinic and the patient gives written informed consent for use of the data for research, the patient is added to our database. The email addresses are added to the online-system. The database sends a preoperative questionnaire automatically close before surgery. In case of missing email addresses, patients who visit the outpatient clinic for reassessment are asked for their email address, so they can receive the questionnaires regarding the next follow-up moments by email. When the patient prefers paper questionnaires, results are manually added to the electronic system.

This online planning system makes it possible to remind patients and nurse practitioners (NP) to send paper questionnaires and to schedule an appointment as well. Thereby a notification on the dashboard of the online-system shows up if we did not receive response to the questionnaire within two weeks. At our institution we use a protocol for non-responders both in the email and paper group. A second questionnaire is sent after two weeks and if we still do not receive response after four weeks since the first effort, the NP calls the patient to remind them. If patients do not want to participate anymore they can be deactivated in the system.

We intend to achieve a full preoperative PROMs data capture rate. Because we collect PROMs in the trauma department too, we are used to complete the questionnaires retrospectively with maximum scores in baseline in case of acute trauma. The pre-operative questionnaires serve as a baseline measurement. The post-operative follow-up protocol consists of a visit to the outpatient clinic after one, three, five, seven and ten years including questionnaires. On every occasion, the surgeon or the NP sees the patient and a plain X-ray is made.

Since the introduction the pre- and postoperative patients’ part of the questionnaires are slightly different. The preoperative questionnaire consists of the Euroqol five dimensions (EQ-5D), the Oxford Elbow Score (OES) and the Visual Analogue pain Scales (VAS 0-10) in rest and activity. Thereby the patient is asked if they did have surgery on their elbow before. If the answer is yes, we want to know when the surgery took place and what kind of surgery it was.

The postoperative questionnaires consist of the EQ-5D, the OES and the VAS 0-10 in rest and activity too. In addition, the patient is asked how satisfied they are with the result of the surgery and whether they would recommend the received therapy for their elbow to colleagues, friends or family members. These questions are answered on a seven-point scale (satisfaction) and ten-point scale (recommendation). Before the introduction the pre- and postoperative questionnaires were the same and consisted of the OES and VAS pain in rest and activity.

For every follow-up moment in each group we determined the number of questionnaires sent and the number of questionnaires we received. We have added these numbers for every group. We compared response rates before and after the introduction of the online database in June 2015. After implementation of the online system we compared the online- and the paper questionnaires group on response rate, completeness and mean age. In addition, we compared the mean age of responders and non-responders in both groups after implementation. Differences on outcome parameters before and after the introduction of the online database were compared using T-tests for normally distributed data and Fisher’s Exact test for dichotomous data.

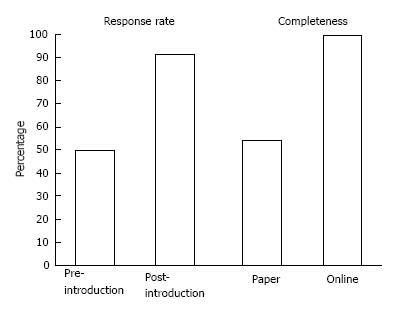

Before June 2015 we achieved an overall response rate of 49.8% on 616 sent questionnaires. After implementation of the online database 143 questionnaires were sent and the response rate increased to 91.6% (P < 0.01) (Figure 1). Using the online system we captured full response rates both in patients who received radiocapitellar prosthesis and patients who received revision surgery. In patients who received a total elbow arthroplasty and those who received a radial head prosthesis response rates of respectively 90.0% and 83.3% were revealed (Table 2).

| Total elbow prosthesis | Radiocapitellar prosthesis | Radial head prosthesis | Revision surgery | Total | |

| Questionnaires sent in total | |||||

| Before introduction | 212 | 24 | 245 | 135 | 616 |

| After introduction | 69 | 8 | 36 | 30 | 143 |

| Response rate (%) | |||||

| Before introduction | 57.90% | 45.80% | 40.40% | 54.10% | 49.80% |

| After introduction | 89.90% | 100% | 83.30% | 100% | 91.60% |

| Email address known (n) | 43 | 5 | 26 | 21 | 95 |

Since the implementation 100 questionnaires were sent on paper and 43 online. We received 92 paper questionnaires and 39 online questionnaires. With a completeness of 54.4% of paper questionnaires, completeness was lower compared to the online questionnaires where we reached full completeness (P < 0.01) (Figure 1). The mean age of 63 years (SD 12) of patients who completed the questionnaires on paper was comparable to the mean age of 59 years (SD 14) of patients in the online group. If we combine non-responders in the paper and online group, non-responders proved to be younger with a mean age of 52 years (SD 19) compared to a mean age of 62 years (SD 13) of responders (P < 0.05). For further details see Table 3.

| Total elbow prosthesis | Radio-capitellar prosthesis | Radial head prosthesis | Revision surgery | Total | |

| Questionnaires sent in total | |||||

| Paper | 49 | 5 | 24 | 22 | 100 |

| Online | 20 | 3 | 12 | 8 | 43 |

| Response rate | |||||

| Paper | 91.90% | 100.00% | 83.30% | 100.00% | 92.00% |

| Online | 90.00% | 100.00% | 83.30% | 100.00% | 90.70% |

| Completeness of questionnaires | |||||

| Paper | 48.90% | 40.00% | 65.00% | 59.10% | 54.40% |

| Online | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

| Mean age (yr) | |||||

| Paper (SD) | 68 (8) | 58 (8) | 50 (14) | 63 (10) | 63 (12) |

| Online (SD) | 68 (8) | 50 (3) | 50 (13) | 55 (16) | 59 (14) |

| Mean age (yr) | |||||

| Responders (SD) | 68 (8) | 55 (7) | 50 (13) | 61 (13) | 62 (13) |

| Non-responders (SD) | 67 (10) | - | 36 (13) | - | 52 (19) |

Since the introduction we have collected 95 (41%) email addresses of all elbow arthroplasty patients. The mean age of patients using an email address was 59 years (SD 14). The mean completion time of online questionnaires was 5.2 min (SD 3). Completion times of paper questionnaires were not available.

The results of the current study are promising with an increase in response rate from 49.8% to 91.6%. After implementation good response rates are reported both for paper and online questionnaires. In addition online questionnaires were more complete compared to paper questionnaires and non-responders proved to be younger compared to responders.

Several factors might have increased the response rate after the introduction of the online system. As the dashboard function reminds the NP to send paper questionnaires and to be aware of non-response of sent questionnaires, structure is provided regarding follow-up moments. Furthermore, the effort that was previously put into collecting and storing paper versions, is now put into attempts to collect the data in non-responders, since this information is easily fed back by the system. In addition, the amount of paper questionnaires decreased since the online system sends online questionnaires automatically. Therefore, less printing of questionnaires, enveloping, filing, and manual transfer of data from the paper questionnaire to the database is needed anymore. Hence, all these factors together resulted in a huge increase of response rate up to 91.6%.

We also observed some interesting findings on questionnaires sent after the introduction of the online system. At first, we obtained full completeness of online questionnaires compared to 54.4% completeness of paper questionnaires. This is another benefit of using an online system. Online it is impossible to skip questions, while in paper questionnaires researchers and clinicians have to deal with incomplete questionnaires, which accounts for data loss. Secondly, in the current study non-responders proved to be younger compared to the mean age of responders. This is comparable to the results of two other studies[5,6]. On the contrary, other studies associated non-response with older age[2,9-11]. The reason of higher non-response rates in younger patients is unclear, but it could be a result of busy lifestyle and low priority in completing questionnaires. With a mean completion time of 5.2 min we think it is reachable to encourage patients to complete our questionnaires. Moreover, in literature the completion times of paper questionnaires are reported to be significant longer compared to online questionnaires when data entry time is studied[7].

The last noticeable results of the study was the relatively high mean age of patients in the current study was, which probably leads to fewer email addresses, because this generation is not used to computers and/or email[9]. Nevertheless, the decision to use this group of patients was conscious since a structured follow-up for patients who received an elbow arthroplasty is important as asymptomatic aseptic loosening may cause irreversible loss of bone stock. Hence, in addition to the increase in response rate by using an online system, the current study revealed: A higher completeness using digital-compared to paper questionnaires, that non-response rate was higher in younger subjects and that online questionnaires only took 5.2 min to complete.

While the response rate increased greatly in questionnaires, no show on follow-up moments at the outpatient clinic is still a problem. Arguments we frequently encounter are high costs of the deductible, not having any complaints of the elbow and dependency of elderly people on relatives for driving. Unfortunately, at the moment there is no scientific evidence on the number of reassessments we need to perform to be sufficient in follow-up. However, if patients do not want to be reassessed at the outpatient clinic, questionnaires can be sent anyway. For future research, with a prolonged follow-up, patterns in PROMs outcomes of elbow arthroplasties may be distinguished, so deterrence may be detected earlier and attacked more effectively by, for example, revision surgery. Therefore, with more data, we hope to be able to predict the clinical course per patient and to provide still better patient care.

The current study has two limitations. At first the time since the introduction of the online system in June 2015 is short. Although time is short, we can already report promising results. Thereby in the future we predict more patients to have an email address. We are convinced this transition from a less online oriented population to a more online oriented population will ensure even better results using an online follow-up system. Further studies are required to evaluate the results on long-term. In addition, the response rate after the implementation of the system could be biased by the effort that was put into collecting questionnaires. Although, this effort could have been put into collecting, since structure was given to follow-up by the dashboard function of the system.

In conclusion, the results of the current study are promising. A structured online system could increase both the response rate and completeness of questionnaires. Further studies are required to report on the mid- and long-term results of the introduction of a structured online follow-up system.

We would like to thank our nurse practitioner, Yvonne de Deugd, for the effort she has put into collecting questionnaires and email addresses.

Since the last decade, several online follow-up systems became available to collect patient reported outcome measures (PROMs). Before these systems became available, all questionnaires were sent manual on paper. In the current study the authors want to report on the advantages and disadvantages of using an online follow-up system.

In 2002, the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Registry started using PROMs on a national scale. Since good response rates were reported in 2011, several other national registries have followed their model. However no literature is available on the effect of introducing an online database. This is the first study reporting on the increased response rate using an online follow-up system.

In the recent years several online databases became available to collect PROMs. The present study represents the effect of introducing an online database on the follow-up of patients who received elbow arthroplasty. The major findings of the study were both an increased response rate and completeness of questionnaires using an online database.

The data in this study suggested that an online follow-up system could both increase the response rate and completeness of questionnaires. According to the findings of the current study, they can recommend the use of an online database in order to improve the follow-up of patients who have received (elbow) arthroplasty.

PROMs are patient reported outcome measures, which are frequently used for follow-up of patients who have received surgery.

Peer-review

It is a well presented, interesting early stage pilot study. Available papers concerning the use of online follow-up databases are rare or non-existing. However, it is about a relevant topic in orthopaedic surgery.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country of origin: The Netherlands

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Drosos GI, Malik H, van den Bekerom MPJ S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Calvert M, Blazeby J, Altman DG, Revicki DA, Moher D, Brundage MD. Reporting of patient-reported outcomes in randomized trials: the CONSORT PRO extension. JAMA. 2013;309:814-822. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 797] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 857] [Article Influence: 77.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Emberton M, Black N. Impact of non-response and of late-response by patients in a multi-centre surgical outcome audit. Int J Qual Health Care. 1995;7:47-55. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Fevang BT, Lie SA, Havelin LI, Skredderstuen A, Furnes O. Results after 562 total elbow replacements: a report from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18:449-456. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Franklin PD, Harrold L, Ayers DC. Incorporating patient-reported outcomes in total joint arthroplasty registries: challenges and opportunities. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:3482-3488. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 59] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hutchings A, Neuburger J, Grosse Frie K, Black N, van der Meulen J. Factors associated with non-response in routine use of patient reported outcome measures after elective surgery in England. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:34. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 102] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Imam MA, Barke S, Stafford GH, Parkin D, Field RE. Loss to follow-up after total hip replacement: a source of bias in patient reported outcome measures and registry datasets? Hip Int. 2014;24:465-472. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kesterke N, Egeter J, Erhardt JB, Jost B, Giesinger K. Patient-reported outcome assessment after total joint replacement: comparison of questionnaire completion times on paper and tablet computer. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2015;135:935-941. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Krenek L, Farng E, Zingmond D, SooHoo NF. Complication and revision rates following total elbow arthroplasty. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:68-73. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 54] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Newhouse N, Lupiáñez-Villanueva F, Codagnone C, Atherton H. Patient use of email for health care communication purposes across 14 European countries: an analysis of users according to demographic and health-related factors. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e58. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 54] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rolfson O, Kärrholm J, Dahlberg LE, Garellick G. Patient-reported outcomes in the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register: results of a nationwide prospective observational study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93:867-875. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 173] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sales AE, Plomondon ME, Magid DJ, Spertus JA, Rumsfeld JS. Assessing response bias from missing quality of life data: the Heckman method. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:49. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |