Published online Oct 21, 2020. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i39.6015

Peer-review started: December 31, 2019

First decision: February 19, 2020

Revised: June 15, 2020

Accepted: October 12, 2020

Article in press: October 12, 2020

Published online: October 21, 2020

Single port laparoscopic surgery allows total colectomy and end ileostomy for medically uncontrolled ulcerative colitis solely via the stoma site incision. While intuitively appealing, there is sparse evidence for its use beyond feasibility.

To examine the usefulness of single access laparoscopy (SAL) in a general series experience of patients sick with ulcerative colitis.

All patients presenting electively, urgently or emergently over a three-year period under a colorectal specialist team were studied. SAL was performed via the stoma site on a near-consecutive basis by one surgical team using a “surgical glove port” allowing group-comparative and case-control analysis with a contemporary cohort undergoing conventional multiport surgery. Standard, straight rigid laparoscopic instrumentation were used without additional resource.

Of 46 consecutive patients requiring surgery, 39 (85%) had their procedure begun laparoscopically. 27 (69%) of these were commenced by single port access with an 89% completion rate thereafter (three were concluded by multi-trocar laparoscopy). SAL proved effective in comparison to multiport access regardless of disease severity providing significantly reduced operative access costs (> 100€case) and postoperative hospital stay (median 5 d vs 7.5 d, P = 0.045) without increasing operative time. It proved especially efficient in those with preoperative albumin > 30 g/dL (n = 20). Its comparative advantages were further confirmed in ten pairs case-matched for gender, body mass index and preoperative albumin. SAL outcomes proved durable in the intermediate term (median follow-up = 20 mo).

Single port total colectomy proved useful in planned and acute settings for patients with medically refractory colitis. Assumptions regarding duration and cost should not be barriers to its implementation.

Core Tip: Single access laparoscopy performed via the stoma site for patient’s sick with ulcerative colitis and needing total colectomy with ileostomy is shown to be appropriate and with some advantages over its multiport equivalent. Operative costs and total hospital stay were significantly reduced with the Single access laparoscopy approach (using a “glove port”) and outcomes were sustained in the intermediate term.

- Citation: Burke J, Toomey D, Reilly F, Cahill R. Single access laparoscopic total colectomy for severe refractory ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol 2020; 26(39): 6015-6026

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v26/i39/6015.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v26.i39.6015

The acceptance of the clear advantages of laparoscopy over open surgery for patients with inflammatory bowel disease[1], particularly in the acute setting[2-4], has been relatively recent[5]. For patients undergoing a total abdominal colectomy for ulcerative colitis (UC), a laparoscopic approach is associated with lower overall complication and mortality rates[6]. However, surgical technique and technology continues to undergo evolutionary change.

Single access laparoscopic (SAL) surgery is a recent modified access technique that allows grouping of laparoscopic instrumentation at a single confined site in the abdomen in order to further minimize the degree of parietal wounding associated with intraperitoneal surgery. Meta-analyses demonstrate that overall, SAL for segmental colorectal resection compared to standard multiport approaches has no difference in conversion to open laparotomy, morbidity or operation time but a significantly shorter total skin incision and a shorter post-operative length of stay is observed[7]. As the size of an ileostomy approximates that of a single port access site, total colectomy with end ileostomy should be ideally suited to this access modality. Early reports demonstrated that with judicious patient selection and considered operative technique, SAL total colectomy for medically UC can be safely performed[8]. To date however, experience analyses have predominantly focused on feasibility and technical adequacy in small series predominantly in the elective setting and mostly without a concurrent comparative cohort[8-12].

Here we analyze, including case-matching, our experience of SAL in a consecutive series of patients requiring planned, urgent or emergency total colectomy for refractory UC in comparison with contemporaneous others in the same departments undergoing multiport access colectomy. The purpose of this study is to examine the role of this access in an all-comers experience reflective of general practice in patients with UC including those with acute severe colitis and those with severe disease and systemic toxicaemia in debilitated condition as indicated by symptoms, endoscopy and biochemistry including albumin and inflammatory markers. This a retrospective study of a clinical experience whose details were recorded prospectively.

All patients presenting for total colectomy with end ileostomy for medically refractory severe UC to a tertiary referral centre over a 36-mo period were considered for inclusion regardless of urgency of presentation. Patients requiring surgery for dysplasia or neoplasia were excluded. Laparoscopic surgery is the standard approach for all colorectal resections in the departments although only one surgeon has trained in SAL. All procedures were performed either solely by a Senior Resident alongside the scrubbed consultant or shared between the two depending on procedure circumstance, difficulty and duration as would be our typical practice within a teaching hospital.

Those patients already in the hospital and those who were referred as out-patients for planned resections were prepared for surgery similarly with the latter routinely being admitted on the morning of surgery. Preoperative mechanical bowel preparation for bowel cleansing was not utilized. All patients were marked for optimal stoma site by a specialist nurse practitioner or senior member of the Surgical Team. A formal Enhanced Recovery Programme with a dedicated nurse specialist was in place over the duration of the study period and implemented uniformly across all surgical teams. All patients received standard anti-thrombosis and antimicrobial prophylaxis and underwent general anesthesia without epidural/spinal anesthesia. The anaesthetized patient was placed in a Trendelenburg position on an anti-slip beanbag and painted and draped in the standard fashion.

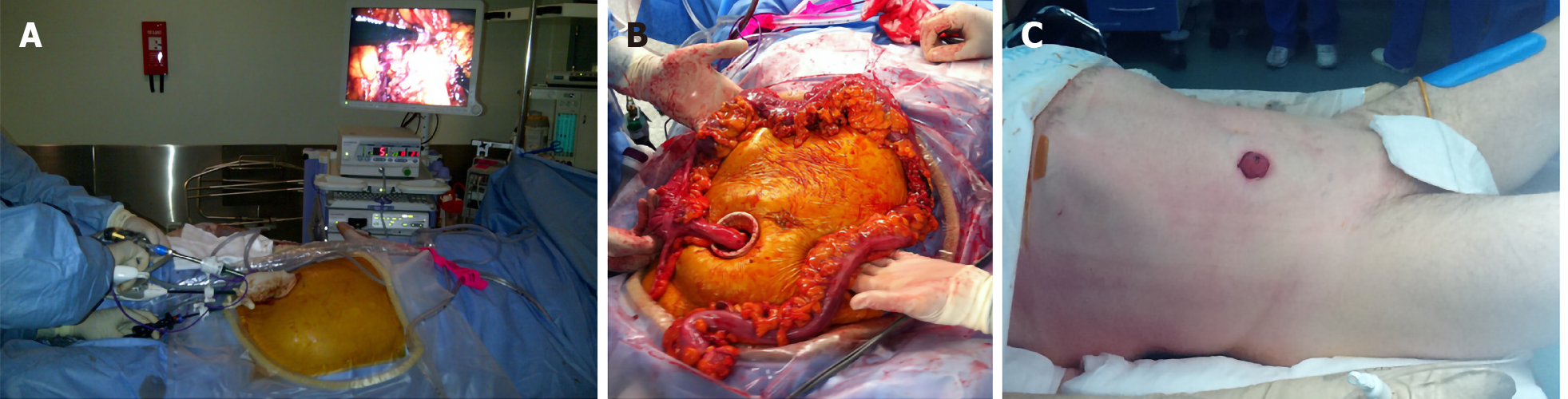

The single port access device of preference was the “Surgical Glove Port”[13]. Constructed table-side, in short, this comprises a standard surgical glove into which laparoscopic trocar sleeves (one 10 mm and two 5 mm) are inserted without needing obturators into three fingers cut at their tips (Figure 1). The ports are tied in position using strips cut from the other glove in the pair and the cuff of the “Glove port” stretched onto the outer ring of a wound protector-retractor (ALEXISTM XS, Applied Medical) sited in the operative access wound.

A local anesthetic block (bupivicaine) was infiltrated around the intended incision site in the right iliac fossa at the site planned ultimately for stoma maturation. A 3 cm skin and fascial incision was measured and made in the appropriate site. On securing safe entry into the peritoneum, a wound protector-retractor was placed into the wound and its outer ring adjusted down to the abdominal wall. The “Glove Port” was then stretched onto the outer ring. The operation was performed using standard rigid laparoscopic instruments, a 10 mm 30o high definition laparoscope (where possible using the EndoeyeTM, Olympus Corporation, which has sterilized in-line optical cabling) along with an atraumatic grasper and an energy sealer-divider (Ligasure, Covidien). Total colectomy with end ileostomy for colitis recalcitrant to medical therapy was performed as previously described[14]. In brief, early rectosigmoid transection was achieved by laparoscopic stapling at the level of the sacral promonitory. Thereafter the operation was performed progressively quadrant by quadrant, working in a close pericolic plane and proceeding distal to proximal until the caecum was reached. After intracorporeal stapling across the distal ileum, the entire colon was then withdrawn “caecum first” via the stoma site. Relaparoscopy was performed via the stoma site and the rectal stump checked in addition to peritoneal lavage and haemostasis control. The end ileostomy was then matured at the single port access site (Figure 2).

The multiport procedure was performed in a conventional fashion typically beginning with an open induction of the pneumoperitoneum in a subumbilical site and thereafter typically employing four additional trocars of between 5 and 10 mm diameter (two on the left side and two on the right). The specimen was extracted either via the stoma site incision or via a separate incision (most commonly a dedicated Pfanniestiel, suprapubic or subumbilical incision). Local anaesthetic was infiltrated at all wounds on completion of the procedure.

SAL was the preferred commencement access of RAC in patients considered potentially suitable (precluding exceptional cases) and so this approach required this surgeon be available. As many patients with UC can undergo planned surgery rather than needing immediate operation this allowed the majority of patients be considered for this approach. There was no especial referral to any particular surgeon for the patients who tended to be seen by the surgeon taking acute referrals at the time of surgical need.

All patients were managed postoperatively using an enhanced recovery protocol. Analgesia was by means of patient-controlled analgesia transitioning to oral medicines once oral diet commenced. Patient with extraction site or laparotomy wounds had local an aesthetic infusion catheters placed at time of wound closure. Nasogastric tubes were routinely removed at procedure completion and the patients are mobilized within the first 6-12 h of surgery. Oral intake was commenced on demand commencing within six hours of surgery and built up steadily as tolerated thereafter. Urinary catheters were removed on the first postoperative day. Intra-abdominal drains and transanal decompressive catheters were placed by surgeon judgment and were removed on or before the third postoperative day.

Departmental approval was agreed in advance of this experience. The technique of SAL was not itself considered experimental as it is a variation of standard multiport laparoscopy that has been already proved valid and feasible and is in common use for other resectional procedures in the department. All patients were fully consented regarding the approach and informed of alternatives. As the intention in treatment was always to ensure safe, effective and efficient surgery, all patients were assured a low threshold for conversion if any deviation from operative plan was encountered. The authors have no conflicts of interest or relevant disclosures to declare with respect to this report.

Patient demographics along with their clinical, haematological, biochemical and radiological profiles and disease characteristics were recorded prospectively on a dedicated database in addition to operative and postoperative details. Access equipment and length of stay costs were determined by the directorate business manager. Postoperative classifications were categorized as by Clavien-Dindo[15]. Unless otherwise stated, data is represented as median (range) and n represents the number of patients included in the analysis. Differences in categorical variables were evaluated using a Pearson's chi-squared test and differences in continuous variables were evaluated using Mann–Whitney U and Student’s t-testing where appropriate (the latter for comparison between paired patients). All calculations were done using SPSS version 12.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

Over the thirty-six month study period, 46 patients with confirmed UC required scheduled, urgent or emergency total colectomy with end ileostomy by a colorectal specialist consultant for medically uncontrolled severe disease alone. Overall, the median age (range) was 38 (19-73) years and median (range) body mass index was 22.8 (17.3-38.9) kg/m2. Twenty-six patients were male. Nine patients had acutely severe disease resulting in clinical deteriorating conditions with toxaemia and low preoperative albumin (< 30 g/dL). Thirteen patients had their surgery performed on scheduled lists while the others were done either urgently (n = 25) or emergently (n = 8). Overall, co-morbidity was low (one patient had multiple sclerosis while two had asthma). Only five patients had had prior abdominal surgery (only one had a prior midline laparotomy and another was a renal transplant recipient).

All patients were considered for a laparoscopic approach ab initio with 39 (85%) having their procedure commenced in such fashion at the attending surgeon’s discretion. 29 of these patients were already inpatient in the hospital under the care of the gastroenterology service for an acute exacerbative episode. The other ten patients were admitted specifically for surgery. 27 patients (59% of total cohort, 69% of those having laparoscopic surgery) had their procedure begun via a single port approach (three on scheduled lists) with a completion rate thereafter of 89% (Table 1). The SAL approach patients were begun consecutively on a non-selected basis with the exception of two patients (7% of this cohort) over the time period who had their operation commenced by multiport laparoscopic access due to exceptional co-morbidity (one had concurrent acute bilateral ileofemoral deep venous thrombosis and steroid psychosis while the other had congenital micrognathia and oesphageotracheal atresia with long-term feeding jejeunostomy) and both were in fact converted to open operations due to extreme friability of the colon. The three “converted” SAL patients had between 1 (n = 2) and three additional trocars inserted for reasons of difficult splenic flexure mobilization, intra-operative evidence of colitis-related perforation and extensive adhesiolysis (related to prior open nephrectomy for trauma) respectively. All patients in the SAL group had their specimens removed via the stoma site incision. Ten other patients had their operation performed by a multiport approach (no conversions) while the remaining seven patients had their operations commenced via laparotomy by other surgeons in the department (Table 2).

| Single port started (n = 27) | Single port completed (n = 24) | Single port completed, preop Alb > 30 (n = 18) | Single port completed, preop Alb < 30 (n = 6) | Multiport started (n = 12) | Multiport completed (n = 13) | Multiport completed, Alb > 30 (n = 12) | |

| Median age (yr) | 37 | 36 | 39 | 34.4 | 36.6 | 37.6 | 41 |

| Range | 19-59 | 19-59 | 19-59 | 29-45 | 18-70 | 31-70 | 33-69 |

| Median BMI (kg/m2) | 23.3 | 23 | 23.5 | 21.4 | 22.2 | 25.8 | 25.9 |

| Range | 18.9-31.8 | 18.9-31.8 | 18.9-31.8 | 20.1-24.7 | 17.3-38 | 17.3-38.9 | 17.3-38.9 |

| Males | 16 (59%) | 14 (58%) | 9 (50%) | 4 (66%) | 4 (33%) | 4 (31%) | 4 (33%) |

| Anti-TNF agents | 16 (59%) | 14 (58%) | 9 (50%) | 5 (83%) | 7 (58%) | 9 (69%) | 8 (66%) |

| Median preop Alb | 36 | 37 | 39 | 24.5 | 38 | 38 | 38 |

| Range | 17-44 | 17-44 | 30-44 | 17-28 | 15-43 | 27-44 | 32-44 |

| Median preop Hb | 12.9 | 12.6 | 13.1 | 10.4 | 11.6 | 11.9 | 12 |

| Range | 7.9-17.2 | 7.9-17.2 | 7.9-17.2 | 8.4-13.2 | 8.2-13.5 | 8.2-14.6 | 8.2-14.6 |

| Median preop CRP | 29 | 25 | 10 | 51 | 9 | 9 | 18.7 |

| Range | 1-221 | 1-221 | 1-53 | 21-221 | 1-7 | 1-71 | 1-71 |

| Total OT time (min) | 290 | 285 | 285 | 275 | 300 | 302 | 301 |

| Range | 100-395 | 100-380 | 100-380 | 250-363 | 200-423 | 200-420 | 200-420 |

| Operative time (min) | 182 | 180 | 180 | 177.5 | 205 | 235 | 230 |

| Range | 90-270 | 90-270 | 90-270 | 150-240 | 120-345 | 120-345 | 120-345 |

| Postop length of stay | 5 | 5 | 5 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 8 | 7 |

| Range | 3-21 | 3-21 | 3-9 | 3-12 | 4-31 | 4-23 | 4-23 |

| Laparotomy commenced (n = 7) | Laparotomy completed (n = 9) | |

| Age (yr) | 49 | 45 |

| Range | 26-73 | 22-73 |

| Males | 6 (85%) | 8 (88%) |

| Preop Alb | 30 | 27 |

| Range | 15-42 | (15-42) |

| Median length of stay | 11 | 16 |

| Range | 7-56 | 7-56 |

The characteristics of the patients undergoing surgery are shown by access (both at start and by completion) in Table 1 and postoperative complications for patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery are shown in Table 3. Overall there was no significant difference between the groups in terms of age, gender, Body mass index (BMI) or preoperative disease suppressant medications and the postoperative morbidity was predominantly reflective of the severity of the disease process rather than of operative access route. One patient in the single port group (4%), required an early return to theatre for a fascial release for an oedematous stoma while, after a median follow-up of 20 mo (range 5-40 mo), two patients (7%) who had single port surgery have had parastomal hernia requiring repair (one done at the same time as completion proctectomy). One patient in the multiport group has complained of a parastomal hernia after an overall mean follow-up of 19 mo (range 1-25 mo).

| Complication grade | Definition by Clavien-Dindo | Single port group (n = 27) | Multiport group (n = 12) | ||

| First 30 d | n | Comment | n | Comment | |

| I | Any deviation from postop course without intervention | 3 | Serous discharge from around stoma site (all patients albumin < 30) | 3 | Persistent pneumoperitoneum with pain; Non-cardiac chest pain, high output stoma |

| II | Pharmacological treatment | 2 | Parastomal wound infection; Portal vein thrombosis treated by anticoagulation diagnoses after discharge | 2 | Parastomal wound infection; Umbilical port infection (pt started single port, converted due to adhesions); Portal vein thrombosis treated by anticoagulation (CT diagnosis on day 2 postop in patient begun multiport and converted to open due to extreme colonic friability) |

| III | Surgical, endoscopic or radiological intervention | 1 | Return to theatre on day 4 postop for fascial release for oedematous stoma (pt with preop Alb < 30) | 2 | Radiological drain of intrabdominal collection in one patient started by single port but converted to multiport laparoscopy and in another started by multiport but converted to open (retroperitoneal colon perforations found at surgery) |

| IV/V | Life-threatening complication/Death | 0 | - | 0 | - |

| After 30 d | Median follow-up 12.3 mo | Median follow-up 10.5 mo | |||

| I | 0 | - | 1 | Parastomal hernia | |

| III | 2 | Both parastomal hernia requiring repair. (One performed at time of complection proctectomy, other requiring urgent laparoscopic repair) | |||

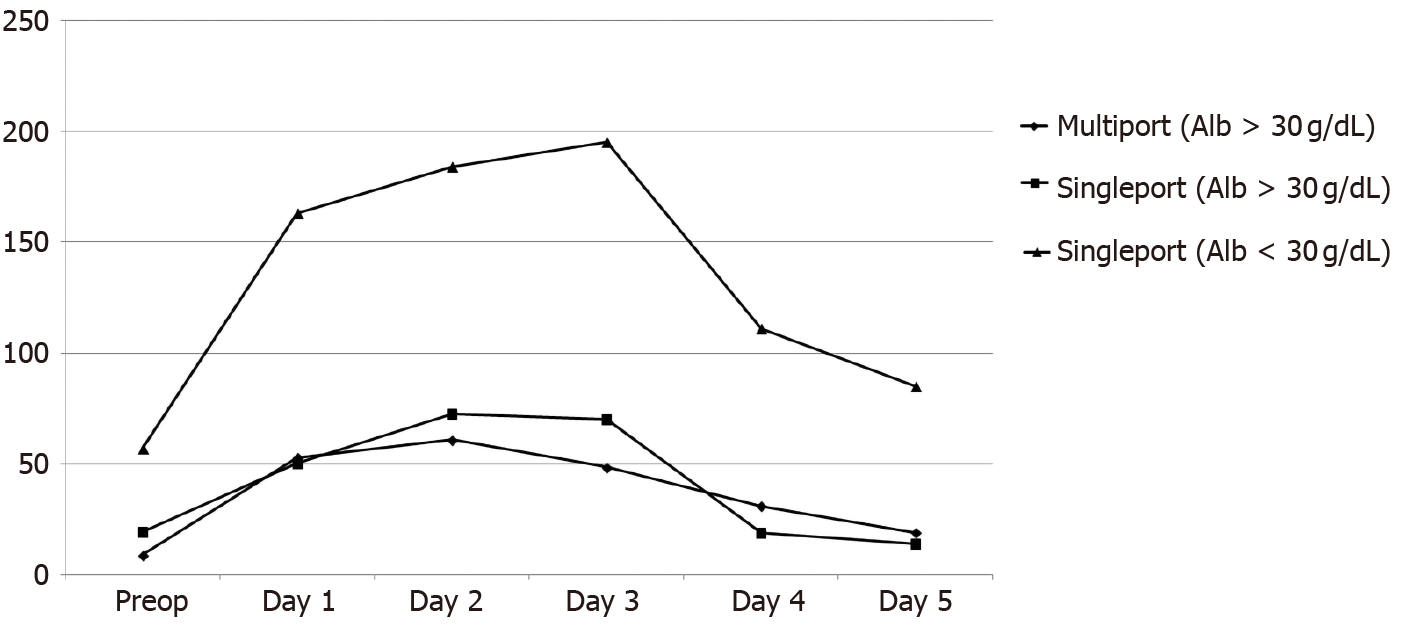

As compared to other patients with preoperative albumin > 30 g/dL, those having laparoscopic surgery with preoperative albumin < 30 g/dL (n = 9, 7 of whom had their procedure started by SAL with one in this group being converted to multiport access) were significantly more likely to be anaemic (median preoperative haemoglobin 10.4 vs 12.25, P = 0.002) and have elevated preoperative (median 10 vs 51, P = 0.03) and postoperative C-Reactive Protein (CRP) levels (Figure 3). They were also more likely to have an urgent or emergent operation and to be converted from their initial access approach whether started by multi-port or single-port.

As a group overall, patients having their surgery by single port access had a significantly shorter postoperative hospital stay (5 d vs 7.5 d, P = 0.045) being especially evident in those who were non-toxic (P = 0.034) and who also had their surgery completed by this access (P = 0.005). Furthermore, these patients were also significantly more often discharged on or before day 5 as compared with patients undergoing multiport surgery (P = 0.04, Pearson Chi-square). While as an overall group the single port patients had trends towards reduced operative time (P = 0.46) and total theatre occupancy (P = 0.85), these did not reach statistical significance. There was also no significance difference overall in terms of resumption of bowel function, postoperative pain scores, analgesia requirements, daily CRP levels or complications. Interestingly, although patients who were toxic and underwent single port surgery had a significantly longer hospital stay (median 9 d, P = 0.03) as well as CRP levels on each day before and after their surgery than those non-toxic patients having the same operation by the same access approach, there was no significant difference in terms of operating length of time or indeed with postoperative length of stay between these patients and those having multiport access (whether as a group overall or those with preoperative albumin > 30 g/dL) with a median hospital stay of 7.5 and 7 d respectively.

Case-matching for gender, albumin > 30 g/dL and BMI (+/-3 kg/m2) in addition to commencement and completion by method of laparoscopic access, surgery type and indication, presented 10 pairs for analysis. Comparison between the groups again shows significant difference in favour for single port surgery for postoperative length of stay, both by group medians (P = 0.02 Student’s t-test) as well as day of discharge on or before day 5 (P = 0.02 Pearson Chi-square) with no significant difference in either operative time or total theatre occupancy. While there was no significant difference in terms of opiate requirement or pain score, the trend was in favour of single port access for opiate requirement (day 3, P = 0.07).

Economically, the cost of the glove port per case is €63.80 (comprising wound protector with three trocar sleeves). Assuming the use of disposable trocars, as compared to a four port trocar technique (comprising a balloon Hassan Port, a 12 mm port with obturator for stapling as well as one 5 mm trocar with obturator and another one without) there is a cost saving of €101.10 per case (a wound protector is also used in the latter cases while both techniques require two staplers fires, an energy sealer and suction/irrigation). The cost of a 24-h stay in our unit has been averaged at €950. Therefore, the total cost saving when a SPLS total colectomy is compared to case matched multiport equivalent is €2476.10.

Aside from isolated cases and small series describing elective colectomy for colitis, the effectiveness and appropriateness of SAL for severe colitis has only recently begun to be specifically reflected in the literature. Its practitioners view SAL as particularly useful for these individuals who are often slim and young and without previous laparotomy and who value body image[16,17]. Psychologically, a minimally invasive approach may also seem less traumatic. Many in addition will need their surgery performed urgently at a time when they are physically and immunologically debilitated and so have an impaired capacity for wound healing. Furthermore, such patients have to come to terms with managing a stoma in the early postoperative period and an ability to concentrate on this alone rather than any additional abdominal wall wounds may be advantageous. Many in this group will also need further surgery in the future for proctectomy with or without restorative ileal pouch-anal reconstruction. Preservation of the majority of the abdominal wall to facilitate future surgery along with the minimization of peritoneal adhesions could therefore be advantageous. SAL may therefore be particularly relevant to this patient cohort.

While prior series have compared patients undergoing SAL and multiport total colectomy[18] or total proctocolectomy and ileal pouch anal anastomosis[19], these have predominantly been performed solely with respect to the elective setting. The current data represents an all comers’ experience, including both planned and urgent total colectomies for ulcerative colitis whether or not the procedure could be included on a scheduled list. Importantly no patient in this cohort is purely elective in that all suffered a debilitating disease requiring operative intervention and indeed most were already inpatients under the gastroenterology service or urgent transfers from outside institutions and were therapeutically immunosuppressed. This is why these patients were chosen to undergo total colectomy and end ileostomy while of course patients presenting purely electively for surgical relief of ulcerative colitis can undergo panproctocolectomy with ileo-anal pouch formation as part of a two stage procedure towards gastrointestinal reconstitution (rather than three stage as is our practice with the sicker medically refractory group). The current data demonstrates that both overall and when matched for gender, preoperative albumin, BMI and method of completion, SAL was directly applicable to this patient group and provided shorter postoperative length of stays without increased operative time then patients undergoing the same operation for the same disease by a multiport access approach.

Preoperative albumin level is a reasonable indicator of preoperative clinical deterioration upon which to case match disease severity[20] as, in general, pre-operative hypoalbuminaemia is associated with increased surgical site infection following gastrointestinal surgery[21] and, specifically for patients undergoing laparoscopic total abdominal colectomy for ulcerative colitis, is associated with reoperation[22]. Furthermore, prior series have shown a higher pre-operative serum albumin is associated with performance of a laparoscopic approach[23]. This study shows that, while the advantages of the single port access are particularly evident in those undergoing their surgery when in a less toxic state, single port access can also be implemented in sicker patients without significantly compromise of theatre or hospital efficiency as compared to patients undergoing multiport total colectomy although the numbers are too limited to define specific comparative advantage in relation to wound healing in this cohort.

Therefore the current experience has shown that SAL allows completion of surgery via the stoma site alone as the only point of transabdominal access, thereby obviating any additional port sites, in the majority of cases. While not the same magnitude of advance that laparoscopy represents over laparotomy (prior to introduction of laparoscopy as access of preference in 2010, the median length of stay for this category of operation overall was ten days in our unit), there are nonetheless advantages for both the patient and healthcare provider. Although the morbidity associated with 5 mm internal diameter trocars is considered minimal, colorectal surgery typically requires a stapler and/or clip applicator and so mandates at least one extra 12 mm port, a diameter more likely to be associated with postoperative complications including discomfort, infection and fascial herniation[24]. Furthermore, the sole site of abdominal wounding is confined to one small area of the parietal wall, a factor likely to favor effective local postoperative analgesic techniques reducing opiate requirements although the current data show did not show a statistically significant difference in this parameter compared between the groups (indeed it is difficult from this data to be specific regarding why exactly the confined access route translated into significantly shortened postoperative hospital stays).

Although demonstrated feasible for colorectal surgery in general[7], some experts continue to feel SAL is undermined by the current expense of the commercially available devices[25]. Our choice of access port obviates this issue proving in fact cheaper than the multi-port equivalent as the surgical glove port needs only trocar sleeves rather than the otherwise necessary obturators. In addition, because these ports are placed into the glove space (and so are in fact extracorporeal) rather than into the patient means that the risk visceral or vascular injury at the time of trocar placement is reduced. However the main advantage of this innovative access modality is its performance which is, in our experience, better than the commercial equivalent by virtue of its elasticity and lack of fulcrum point (permitting enhanced horizontal, vertical and rotational maneuverability as well as augmented instrument tip ab/adduction and triangulation) while being equally stable and durable during a case. Furthermore, the device is always available (without needing prepurchasing), applicable to every patient regardless of body wall depth (due to the adaptable wound protector-retractor component) and is associated with no financial penalty if conversion to a multiport or open operation is required due to the specifics of the patient or case. Also there were no costs accrued due to loss of theatre efficiency, in fact the operative time of a SAL total colectomy tended to be shorter than its multiport equivalent (although interestingly any potential gain in this aspect is noticeably offset by the fact overall theatre occupancy was the same reflecting a need for engagement and focus of the entire perioperative team in order to maximize any potential gain associated with innovation in operative access). One of the primary delays following colorectal resection is patient education in ostomy care. The shortened hospital stay associated with a laparoscopic approach, particularly SAL, can increase demands on the stoma education service that traditionally has had several days to get to know the patient and provide appropriate training. However, the dedicated nurse practitioners in our unit have responded to this issue by providing additional visits, commencing preoperatively. The reduced period of ileus facilitates early eating and increased opportunity to gain experience in ostomy management.

While the relatively small numbers of patients in this study period is a limitation of the study, this experience does still represent the largest reported experience of single port total colectomy with end ileostomy for recalcitrant ulcerative colitis to date. The published experience even regarding multiport total colectomy is also relatively small as these cases present relatively infrequently even in large centres with most groups tending to publish figures that at most approximate 20 cases annually. There is in addition a possible bias in that choice of surgical approach reflected surgeon experience. We have tried to control for this aspect by including case match analysis rather than crude group analysis overall. Furthermore, the operations presented here were never solely done by one operator alone but included resident performance of the majority of the procedure in most cases as is routine for all cases in our university teaching hospital. The postoperative care pathways are shared for all patients also including common postoperative care pathways and protocols in addition to common ward rounds and allied health professional input in all cases. Certainly, further experience with larger patient numbers is required to understand why exactly patients are significantly more likely to be discharged earlier when having their surgery by single access vs the conventional, standard multiport approach. Lastly, single port access itself can impose technical limitations on surgeons performing this aspect and its usefulness of course relates to experience across the discipline and our practice incudes its employment in elective surgery for neoplasia either for part or the entirety of the operation in addition to its employment for such multiquadrant operating as for this indication. We have found empirically however that its need for only two experienced surgeons and very limited instrument set-up does seem positive in the case of urgent operations which often in our institution take place at inconvenient times and in general, non-specialist and emergency operating theatres.

In conclusion, SAL represents an adapted laparoscopic access technique that can safely and effectively allow total colectomy with end ileostomy in the majority of patients with medically uncontrolled ulcerative colitis in both scheduled and acute settings. Not only does it not need to be associated with increased costs either in terms of access devices or theatre efficiency, it can in fact be an economically favorable option that enables earlier discharge from hospital.

SAL was confirmed as a therapeutic option for surgical approach for patients with UC and should be considered more often where the skillsets and technology exist.

Single access laparoscopy (SAL) is a modification of standard laparoscopy that has not be studied in detail for the operation of total colectomy in patients sick with ulcerative colitis (UC). Here we examine its impact in this patient cohort.

Clinical outcomes were examined along with measure of operative efficiency to define the comparative advantages of the SAL approach for this surgery.

SAL was safely and efficiently applied meaning this approach can be considered in future for this patient group.

Clinical data along with patient demographics and outcomes including complications.

SAL was associated with satisfactory outcomes in patients sick with UC and compared favourably to standard surgery in terms of cost and operative time.

SAL was confirmed as a therapeutic option for surgical approach for patients with UC and should be considered more often where the skillsets and technology exist.

Further work can expand on this series in particular to show the generalisability of these findings and also define better the relative merits of the different operative approaches now available.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Ireland

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Bandyopadhyay SK, Weiss H, Yang MS S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Holder-Murray J, Zoccali M, Hurst RD, Umanskiy K, Rubin M, Fichera A. Totally laparoscopic total proctocolectomy: a safe alternative to open surgery in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:863-868. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fowkes L, Krishna K, Menon A, Greenslade GL, Dixon AR. Laparoscopic emergency and elective surgery for ulcerative colitis. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:373-378. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Champagne B, Stulberg JJ, Fan Z, Delaney CP. The feasibility of laparoscopic colectomy in urgent and emergent settings. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1791-1796. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nash GM, Bleier J, Milsom JW, Trencheva K, Sonoda T, Lee SW. Minimally invasive surgery is safe and effective for urgent and emergent colectomy. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:480-484. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Telem DA, Vine AJ, Swain G, Divino CM, Salky B, Greenstein AJ, Harris M, Katz LB. Laparoscopic subtotal colectomy for medically refractory ulcerative colitis: the time has come. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1616-1620. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 54] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Causey MW, Stoddard D, Johnson EK, Maykel JA, Martin MJ, Rivadeneira D, Steele SR. Laparoscopy impacts outcomes favorably following colectomy for ulcerative colitis: a critical analysis of the ACS-NSQIP database. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:603-609. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Maggiori L, Gaujoux S, Tribillon E, Bretagnol F, Panis Y. Single-incision laparoscopy for colorectal resection: a systematic review and meta-analysis of more than a thousand procedures. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:e643-e654. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 80] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cahill RA, Lindsey I, Jones O, Guy R, Mortensen N, Cunningham C. Single-port laparoscopic total colectomy for medically uncontrolled colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:1143-1147. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 52] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Leblanc F, Makhija R, Champagne BJ, Delaney CP. Single incision laparoscopic total colectomy and proctocolectomy for benign disease: initial experience. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:1290-1293. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 42] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Geisler DP, Kirat HT, Remzi FH. Single-port laparoscopic total proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: initial operative experience. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:2175-2178. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 44] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gash KJ, Goede AC, Kaldowski B, Vestweber B, Dixon AR. Single incision laparoscopic (SILS) restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:3877-3880. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fichera A, Zoccali M, Gullo R. Single incision ("scarless") laparoscopic total abdominal colectomy with end ileostomy for ulcerative colitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1247-1251. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hompes R, Lindsey I, Jones OM, Guy R, Cunningham C, Mortensen NJ, Cahill RA. Step-wise integration of single-port laparoscopic surgery into routine colorectal surgical practice by use of a surgical glove port. Tech Coloproctol. 2011;15:165-171. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Moftah M, Sehgal R, Cahill RA. Single port laparoscopic colorectal surgery in debilitated patients and in the urgent setting. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2012;58:213-225. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205-213. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18532] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22008] [Article Influence: 1100.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Polle SW, Bemelman WA. Surgery insight: minimally invasive surgery for IBD. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;4:324-335. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Muller KR, Prosser R, Bampton P, Mountifield R, Andrews JM. Female gender and surgery impair relationships, body image, and sexuality in inflammatory bowel disease: patient perceptions. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:657-663. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 118] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fichera A, Zoccali M, Felice C, Rubin DT. Total abdominal colectomy for refractory ulcerative colitis. Surgical treatment in evolution. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1909-1916. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Costedio MM, Aytac E, Gorgun E, Kiran RP, Remzi FH. Reduced port vs conventional laparoscopic total proctocolectomy and ileal J pouch-anal anastomosis. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:3495-3499. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wang C, He L, Zhang J, Ouyang C, Wu X, Lu F, Liu X. Clinical, laboratory, endoscopical and histological characteristics predict severe ulcerative colitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60:318-323. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hennessey DB, Burke JP, Ni-Dhonochu T, Shields C, Winter DC, Mealy K. Preoperative hypoalbuminemia is an independent risk factor for the development of surgical site infection following gastrointestinal surgery: a multi-institutional study. Ann Surg. 2010;252:325-329. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 217] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Gu J, Stocchi L, Remzi F, Kiran RP. Factors associated with postoperative morbidity, reoperation and readmission rates after laparoscopic total abdominal colectomy for ulcerative colitis. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:1123-1129. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chung TP, Fleshman JW, Birnbaum EH, Hunt SR, Dietz DW, Read TE, Mutch MG. Laparoscopic vs. open total abdominal colectomy for severe colitis: impact on recovery and subsequent completion restorative proctectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:4-10. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 59] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Vilos GA, Ternamian A, Dempster J, Laberge PY; Clinical Practice Gynaecology Committee. Laparoscopic entry: a review of techniques, technologies, and complications. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2007;29:433-447. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 238] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Champagne BJ, Lee EC, Leblanc F, Stein SL, Delaney CP. Single-incision vs straight laparoscopic segmental colectomy: a case-controlled study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:183-186. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 109] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |