Published online Apr 28, 2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i16.1734

Peer-review started: March 13, 2018

First decision: March 30, 2018

Revised: April 1, 2018

Accepted: April 16, 2018

Article in press: April 16, 2018

Published online: April 28, 2018

Diversion colitis is characterized by inflammation of the mucosa in the defunctioned segment of the colon after colostomy or ileostomy. Similar to diversion colitis, diversion pouchitis is an inflammatory disorder occurring in the ileal pouch, resulting from the exclusion of the fecal stream and a subsequent lack of nutrients from luminal bacteria. Although the vast majority of patients with surgically-diverted gastrointestinal tracts remain asymptomatic, it has been reported that diversion colitis and pouchitis might occur in almost all patients with diversion. Surgical closure of the stoma, with reestablishment of gut continuity, is the only curative intervention available for patients with diversion disease. Pharmacologic treatments using short-chain fatty acids, mesalamine, or corticosteroids are reportedly effective for those who are not candidates for surgical reestablishment; however, there are no established assessment criteria for determining the severity of diversion colitis, and no management strategies to date. Therefore, in this mini-review, we summarize and review various recently-reported treatments for diversion disease. We are hopeful that the information summarized here will assist physicians who treat patients with diversion colitis and pouchitis, leading to better case management.

Core tip: Diversion colitis is characterized by inflammation of the mucosa in the defunctioned segment of the colon after colostomy or ileostomy. The vast majority of diverted patients remain asymptomatic, however diversion colitis occurs in almost all diverted patients. Pharmacologic treatment using short-chain fatty acids, mesalamine, or corticosteroids are reportedly effective for those who are not candidates for surgical reestablishment; however, there are no established assessment criteria for determining the severity of diversion colitis, and no management strategies to date. In this mini-review, we summarize and review various recently-reported diversion disease treatments. We hope this review will be useful for future treatment.

- Citation: Tominaga K, Kamimura K, Takahashi K, Yokoyama J, Yamagiwa S, Terai S. Diversion colitis and pouchitis: A mini-review. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(16): 1734-1747

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v24/i16/1734.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i16.1734

Diversion colitis was first described by Morson et al[1] in 1974 as a non-specific inflammation in the diverted colon. Glotzer et al[2] labeled this inflammation “diversion colitis” in 1981. Since then, the disease has been reported in both retrospective[3-20] and prospective studies[21-27] which have described the characteristic clinical, endoscopic, and pathological findings. Surprisingly, the prospective study reported that almost all cases exhibit colitis, evidenced by endoscopic analyses, 3 to 36 mo after the colostomy[21]. Symptomatic cases make up only around 30% of all cases diagnosed via endoscopic studies, and the precise pathogenesis of this condition remains unclarified. Although a wide range of symptoms are reportedly associated with the disease, including abdominal discomfort, tenesmus, anorectal pain, mucous discharge, and rectal bleeding[3,4], there are no established diagnostic criteria for assessing disease severity. Diversion pouchitis is similar to diversion colitis, featuring inflammation of the ileal pouch that results from fecal stream exclusion and the subsequent lack of nutrients from luminal bacteria. Therefore, the difference between the pouchitis and diversion puchitis is whether the lesion is exposed to the fecal stream or not. Patients generally present with varying symptoms such as tenesmus, bloody or mucus-like discharge, and abdominal pain[28]. The incidence of diversion pouchitis is unknown; however, it appears more commonly in patients with underlying inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Nonsurgical approaches for the treatment of diversion pouchitis include the use of short chain fatty acids (SCFA), topical 5-aminosalicylic acids, and topical glucocorticoids. Unfortunately, efficacy study outcomes are conflicting, and the only curative approach is surgical re-anastomosis with the reestablishment of gut continuity[28-30].

In their 1989 examination of non-surgical treatment options procedure, Harig et al[5] reported the efficacy of short-chain fatty acids. The usefulness of the 5-ASA enema in patients with diversion colitis was reported for the first time by Triantafillidis et al[31] in 1991; Glotzer et al[2] reported the efficacy of steroid enemas in patients with diversion colitis in 1984, and similar results were subsequently reported by Lim et al[32] and Jowett et al[33]. Nonsurgical treatments include short-chain fatty acids, 5-aminosalicylic acids, glucocorticoids, antibiotics, and so on. However, due to the lack established assessment methods, the efficacy of these treatments has not been clearly confirmed. Consequently, surgical re-anastomosis remains the most reliable and effective treatment option. There is an unmet need for a summary of these therapeutic options and information regarding the disease assessment, and this need informed the present literature review. We believe that the information summarized in this mini-review will help physicians treat cases and, by increasing the number of treated cases, we will support the establishment of novel criteria for disease assessments and therapeutic decision trees.

A literature search was conducted using PubMed and Ovid, with the terms “diversion colitis” or “diversion proctitis” and “diversion pouchitis” used to extract studies published over the preceding 45 years. All appropriate English-language publications from relevant journals were selected. We summarized the available information on demographics, clinical symptoms, endoscopic and histological findings, treatment, and the clinical course.

A total of 69 articles, including 25 case reports, were matched to our definition of diversion colitis and pouchitis assessment; this information is summarized in Tables 1 and 2. Based on our review, the prevalence estimates of these conditions appear extremely high, reaching almost the entire population of interest if the phenomenon is followed prospectively, beginning at 3 to 36 mo after colostomy[21]. In a recent study, Szczepkowski et al[3] described more than 90% incidence of diversion colitis on endoscopy in a series of 145 patients. The study further reported that there were no significant associations between diversion colitis and age, sex, type of stoma, or mode of surgery performed. The frequency of disease occurrence ranged from 70%-74% in patients without pre-existing IBD[22] and 91% in patients with pre-existing IBD[6,21]. In patients with histories of Crohn’s disease chronic severe inflammation, often with transmural disease, has been described after defunctioning colostomies[34]. It has also been hypothesized that diversion colitis may be a risk factor for ulcerative colitis in predisposed individuals, and that ulcerative colitis can be triggered by anatomically discontinuous inflammation in the large bowel[35]. Among the 46 reported cases of diversion colitis and pouchitis, there was a slight male predominance (28 males, 18 females), and the age of the patients ranged from 3 to 85 years old[2,5,13,29,31-33,35-52]. The period from diagnosis to surgical treatment was a median of 8 mo, ranging from 2 wk to 25 years (Table 1). The types of diversions included: 9 cases of loop sigmoid colostomy; 3 cases of end sigmoid colostomy; 9 cases of loop transverse colostomy; 4 cases of loop ileostomy; 7 cases of ileostomy and colostomy; 3 cases of proctocolectomy; 2 cases of Hartmann’s type with colostomy; and only one case of other operations (Table 1).

| Case (No) | Reference | Reporting yr | Country | Age (yr) | Gender(male/female) | Primary illness(reason for diversion) | Type of diversion (surgical procedure) | Period of up to diagnosis from operation | Symptoms | Endoscopy findings | Pathological findings | Diagnosis |

| 1 | Glotzer et al[2] | 1981 | United States | 49 | M | Free perforation sigmoid diverticulum | Loop sigmoid colostomy | 2.5 mo | No symptoms | Erythema, friability, petechiae, atrophy | Crypt abscess, surface epithelial cell degeneration, acute inflammation, chronic inflammation, regeneration | Diversion colitis |

| 56 | F | Adenocarcinoma. Protect low anastomosis | Loop transverse colostomy | 3 mo | No symptoms | Erythema, friability, petechiae | Normal | Diversion colitis | ||||

| 78 | M | Sigmoid diverticulitis with perforation | Loop sigmoid colostomy | 6 mo | No symptoms | Erythema, friability, granularity | No biopsy | Diversion colitis | ||||

| 70 | F | Sigmoid diverticulitis found at pelvic operation | Loop sigmoid colostomy | 3 mo | No symptoms | Erythema, friability, nodularity | Regeneration | Diversion colitis | ||||

| 43 | F | Sigmoid diverticulitis with perforation | Loop sigmoid colostomy | 8 mo | No symptoms | Erythema, friability | Crypt abscess, acute inflammation. | Diversion colitis | ||||

| 41 | F | Fecal incontinence secondary to cordotomy for pain | Loop sigmoid colostomy | 18 mo | No symptoms | Erythema, friability, petechiae | No biopsy | Diversion colitis | ||||

| 65 | M | Sigmoid diverticulitis with perforation | Loop transverse colostomy | 3 yr | No symptoms | Erythema, friability, granularity, petechiae, inflammatory polyp | Crypt abscess, surface epithelial cell degeneration, chronic inflammation, regeneration. | Diversion colitis | ||||

| 83 | M | Sigmoid diverticulitis with perforation | Loop transverse colostomy | 6 mo | No symptoms | Erythema, friability, granularity | Crypt abscess | Diversion colitis | ||||

| 26 | M | Fecal incontinence after T9-10 cord transection | Loop transverse colostomy | 7 yr | Rectal discharge | Erythema, friability, petechiae | Surface epithelial cell degeneration, chronic inflammation. | Diversion colitis | ||||

| 70 | M | Colonic ileus secondary to anticholinergics for Parkinson's disease | Loop transverse colostomy | 4 mo | No symptoms | Erythema, friability, petechiae, inflammatory polyp | Crypt abscess | Diversion colitis | ||||

| 2 | lusk et al[39] | 1984 | United States | 28 | M | Perforated sigmoid colon for gunshot | Loop sigmoid colostomy | 6 wk | No symptoms | Red granular rectum with aphthous ulcers | Moderate loss of goblet cells with focal edema and lymphocytosis of the lamina propria. | Diversion colitis |

| 68 | M | Sigmoid carcinoma | Loop transverse colostomy | 6 wk | No symptoms | Multiple aphthae | Not obtained | Diversion colitis | ||||

| 3 | Scott et al[46] | 1984 | United States | 21 | M | Gunshot | Loop transverse colostomy | 2 mo | No symptoms | Multiple, small, polypoid lesions in the rectum and sigmoid colon up to the cutaneous part of the mucous fistula. | Mucosal biopsies of the rectal lesions were interpreted as “chronic nonspecific colitis with pseudopolyps, probably from diversion colitis”. | Diversion colitis |

| 4 | Korelitz et al[42] | 1984 | United States | 22 | F | Crohn's Disease | Ileostomy and subtotal colectomy | 2 yr | No symptoms | Friable, nodular | Not obtained | Diversion colitis |

| 34 | F | Crohn's ileitis | Ileocolic anastomosis and Loop ileostomy | 2 yr | No symptoms | Exudate | Focal chronic inflammation, edema, erosions, and an increased number of lymphoid follicles. | Diversion colitis | ||||

| 31 | M | Crohn's ileitis | Ileocolic anastomosis and Loop ileostomy | 1 yr | No symptoms | Aphthous lesions | Chronic inflammation | Diversion colitis | ||||

| 32 | M | Crohn's ileitis | Ileocolic anastomosis and Loop ileostomy | 1 yr | No symptoms | Friable, exudate | Not obtained | Perforation due to complication of barium enema and diversion colitis | ||||

| 5 | Fernand et al[40] | 1985 | United States | 67 | F | Perforated sigmoid diverticulum | Loop sigmoid colostomy | 22 yr | Rectal bleeding | N/A | Diffuse multiple superficial ulcerations and intense inflammatory infiltrates composed mainly of plasma cells, lymphocytes, and some eosinophils. | Diversion colitis |

| 6 | Frank et al[13] | 1987 | United States | 38 | M | Perineal laceration as result of a motor vehicle accident | End sigmoid colostomy | 1 yr | Rectal bleeding | Diffuse nodularity and ulceration | Moderate to severe nonspecific inflammation. | Diversion colitis |

| 7 | Harig et al[5] | 1989 | United States | 63 | M | Neurogenic fecal incontinence | Mucus fistula | 13 mo | Bloody discharge | Endoscopic index of 10 | Inflammatory infiltrate of both acute and chronic cells in the lamina propria and the crypt abscess. Lining epithelial cells show decreased mucin secretion. | Diversion colitis |

| 63 | F | Irradiation of rectum | Mucus fistula | 2 wk | Bloody discharge | Endoscopic index of 10 | Erosions, surface exudate, crypt abscesses, edema. | Diversion colitis | ||||

| 54 | M | Perianal fistulas | Rectosigmoid pouch | 35 mo | Bloody discharge | Endoscopic index of 9 | Lymph follicles | Diversion colitis | ||||

| 56 | M | Diverticulitis | Mucus fistula | N/A | N/A | Endoscopic index of 8 | N/A | Diversion colitis | ||||

| 8 | Triantafillidis et al[31] | 1991 | Greece | 64 | F | Diverticula with perforation | Hartman's type of operation laparotomy | 16 mo | Bloody rectal discharge | Endoscopic index of 9 (quite inflamed with friability and erythema) | Severe inflammatory infiltration, formation of lymph follicles, surface erosions, edema, and crypt abnormalities. | Diversion colitis |

| 9 | Tripodi et al[43] | 1992 | United States | 85 | F | Small bowel perforation with a ruptured chronic pelvic abscess secondary to diverticular disease | End transverse colostomy | 10 wk | Bloody rectal discharge | Erythematous and friable, with diffuse exudation, petechiae, and ulceration | Acute and chronic inflammation with cryptitis. | Diversion colitis |

| 10 | Lu et al[38] | 1995 | United States | 45 | F | Chronic constipation | Loop transverse colostomy | 25 yr | Sepsis(no symptoms such as rectal bleeding) | Large ulcers with overlying pseudomembrane | Infiltration primarily with plasma cells and lymphocytes was noted, as well as a moderate numbers of polymorphonuclear cells, large lymphoid aggregates were seen in the lamina propria | Diversion colitis |

| 11 | Lai et al[47] | 1997 | United States | 49 | M | Intractable ileus,C6 ASIAB tetraplegic | Colostomy | 10 yr | Rectal pain and bleeding. | Partial stricture 70 cm proximally to the rectum. The colonic mucosa appeared granular and friable with evidence of linear ulceration. | Extravasation of erythrocytes, lymphocytic and neutrophilic cells infiltrates, and edema were present within the lamina pro-pria. No evidence of malignancy and glandular dysplasia was found. Pathologic report was consistent with chronic colitis. | Diversion colitis |

| 12 | Lim et al[32] | 1999 | United Kingdom | 60 | F | Faecal incontinence for DM | End sigmoid colostomy | 6 mo | Blood and mucus per rectum | Edematous mucosa with bloodstained mucopurulent exudate | Active chronic colitis with focal cryptitis and crypt abscesses. | Diversion colitis → UC |

| 16 | M | Imperforate anus | Ileostomy and colostomy | 6 mo | Blood and mucus per rectum | Granular, erythematous mucosa with contact bleeding | Active inflammation with polymorphs infiltrating crypts and a diffuse increase in lymphocytes and plasma cells in the lamina propria. | Diversion colitis → UC | ||||

| 13 | Jowett et al[33] | 2000 | United Kingdom | 75 | F | Faecal incontinence | End colostomy | 8 mo | Blood and mucus per rectum | Granular, congested, and oedematous mucosa with contact bleeding | Mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate with distortion of the crypt architecture and cryptitis. | Diversion colitis (→ UC) |

| 14 | Lim et al[35] | 2000 | United Kingdom | 66 | M | Sigmoid carcinoma | Hartmann’s procedure with colostomy. | 18 mo | No symptoms | Mildly inflamed | Active colitis | Diversion colitis (→ UC) |

| 15 | Kiely et al[36] | 2001 | United Kingdom | 6 | M | Ulcerative colitis | Total colectomy and ileostomy | 9 mo | Rectal bleeding | Endoscopic index of 8 | Lymphoid hyperplasia, lymphoplasmacytosis, crypt abscesses and moderate mucosal architectural disruption. | Diversion proctocolitis |

| 3 | M | Perforated typhoid disease | Subtotal colectomy and ileostomy | 5 mo | Rectal bleeding and abdominal pains | Endoscopic index of 8 | Lymphoplasmacytic infiltration of lamina propria, and architectural disruption. | Diversion proctocolitis | ||||

| 8 | F | Aplastic anemia, a large solitary rectal ulcer | Loop sigmoid colostomy | 4 mo | Rectal discharge | Endoscopic index of 9 | Lymphoplasmacytic and neurophilic infiltrate in the lamina propria, mucin depletion, and Paneth cell metaplasia. | Diversion proctocolitis | ||||

| 3 | M | Hirschsprung's disease | ileostomy | N/A | Rectal bleeding | Florid colitis | Lymphoid hyperplasia, lymphoplasmacytosis and mucin depletion, | Diversion proctocolitis | ||||

| 10 | M | Rectovesical fistula | Loop sigmoid colostomy | N/A | Rectal discharge | Florid colitis | Lymphoid hyperplasia, lymphoplasmacytosis. | Diversion proctocolitis | ||||

| 16 | Komuro et al[41] | 2003 | Japan | 46 | M | Ascending colon diverticular perforation (systemic lupus erythematosus and chronic renal failure) | Loop transverse colostomy | N/A ( On surveillance colonoscopy) | No symptoms | Mild colitis with a decreased vascular pattern, oedema and mucosal tear | N/A | Diversion colitis |

| 17 | Tsironi et al[48] | 2006 | United Kingdom | 40 | M | UC pancolitis-type | Rectal stump and ileostomy, subtotal colectomy and ileostomy | 5 mo | Blood and mucus per rectum | Severe chronic inflammation with ulceration and numerous inflammatory polyps | Diffuse chronic inflammation with patchy cryptitis | Divesion collitis with caused by clostridium difficile infection. |

| 18 | Boyce et al[37] | 2008 | United Kingdom | 29 | M | Life-long constipation | Subtotal colectomy | 15 yr | Rectal bleeding and anal pain | The mucosa of the rectal stump was found to be chronically inflamed and ulcerated. | Inflammatory change | Diversion pouchitis |

| 19 | Haugen et al[49] | 2008 | United States | 36 | F | Faecal incontinence due to spina bifida | Laparoscopic sigmoid colostomy and creation of a Hartmann's pouch | N/A | Rectal discharge | N/A | N/A | Diversion colitis |

| 20 | Talisetti et al[50] | 2009 | United States | 19 | F | Megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome (MMIHS) | Gastrostomy and ileostomy | 4 yr | Abdominal pain and rectal bleeding | Friable mucosa with areas of pinpoint hemorrhage from the anal verge to 30 cm proximally | Acute cryptitis and scattered crypt abscesses, consistent with diversion colitis. | Diversion colitis |

| 21 | Kominami et al[51] | 2013 | Japan | 84 | M | Angiodysplasia S/O | Subtotal colectomy and ileostomy | 5 yr | Blood in the stool | Granular, edematous mucosa with contact bleeding | Lymphoplasmacytic and neurophilic infiltrate in the lamina propria. | Diversion colitis |

| 22 | Watanabe et al[44] | 2014 | Japan | 76 | F | UC | 3-stage pancolectomy with construction of an IPAA | 13 yr | Bloody purulent rectal discharge | Severely active pouchitis with large erosions | N/A | Diversion pouchitis |

| 23 | Gundling et al[45] | 2015 | Germany | 75 | F | Chronic constipation | Permanent end-colostomy | N/A | Tenesmus and severe rectal pain | Severe DC was seen on colonoscopy | Confirmed histologically | Diversion colitis |

| 24 | Matsumoto et al[52] | 2016 | Japan | 65 | M | UC pancolitis-type | Subtotal colectomy and ileostomy | 4 mo | Rectal bleeding | Moderate mucosal inflammation | Ulcer, granulation tissue and epithelial defect | Diversion colitis or exacerbation of UC was suspected. |

| 25 | Custon et al[29] | 2017 | United States | 44 | M | UC complicated by colitis-associated low-grade dysplasia | Total proctocolectomy with 2-stage IPAA | 7 yr | Blood in the stool | Edematous and coated with old and fresh blood | N/A | Severe diversion pouchitis |

| Case (No) | Ref. | Age (yr) | Gender(male/female) | Ineffective treatment | Effective treatment | Prognosis |

| 1 | Glotzer et al[2] | 49 | M | N/A | Closure 4 mo post-diversion | Asymptomatic. Proctoscopy and biopsy normal 2.5 and 30 mo postclosure. |

| 56 | F | N/A | Closure 3 mo post-diversion | Recurrent Ca. Mucosa not inflamed grossly or microscopically 18 mo post closure. | ||

| 78 | M | N/A | Closure 6 mo post-diversion | Asymptomatic 1 yr postclosure. | ||

| 70 | F | N/A | Closure 5 mo post-diversion | Asymptomatic. Normal sigmoidoscopy 2 mo postclosure. | ||

| 43 | F | N/A | Closure 2 yr post-diversion | Asymptomatic. Normal sigmoidoscopy 3 yr postclosure. | ||

| 41 | F | N/A | None | Asymptomatic 2 yr after ileostomy. | ||

| 65 | M | N/A | None | Abdominal cramps purulent rectal discharge. Continued inflammation 8 yr after colostomy. | ||

| 83 | M | N/A | None | Asymptomatic. Continued mild inflammation 4.5 yr after colostomy. | ||

| 26 | M | N/A | Steroid enemas | Inproved. Continued 8 yr after colostomy. | ||

| 70 | M | N/A | Steroid enemas | Tenesmus, discharge and fever 4 yr after colostomy. Resolved with steroid enemas. Continued inflammation at 8 yr. | ||

| 2 | Lusk et al[39] | 28 | M | - | Colostomy closure | Normal at 16 mo follow-up. |

| 68 | M | - | Colostomy closure | Normal at 7 wk after clousure. | ||

| 3 | Scott et al[46] | 21 | M | - | Colostomy closure | One month later, the patient was examined by flexible sigmoidoscopy, which demonstrated normal mucosa throughout with no sign of pseudopolyps. |

| 4 | Korelitz et al[42] | 22 | F | Steroid enemas | Ileocolic reanastomosis (ileostomy closure) | 3 mo (interval from reanastomosis to normal sigmoidoscopy), 7 yr (duration normal). |

| 34 | F | - | Ileostomy closure | 1 mo (interval from reanastomosis to normal sigmoidoscopy), 2 yr (duration normal). | ||

| 31 | M | - | Ileostomy closure | 3 mo (interval from reanastomosis to normal sigmoidoscopy), 18 mo (duration normal). | ||

| 32 | M | - | Ileostomy closure | 2 mo (interval from reanastomosis to normal sigmoidoscopy), 14 mo (duration normal). | ||

| 5 | Fernand et al[40] | 67 | F | - | Left hemicolectomy and left salpingo-oophorectomy | She recoverd well and discharged 9 d later. |

| 6 | Frank et al[13] | 38 | M | Oral and topical steroids | Abdominoperineal resection of the diverted loop and permanent colostomy | No evidence of inflammatory bowel disease has developed. Barium study of the small bowel was normal 1 yr after surgery. |

| 7 | Harig et al[5] | 63 | M | N/A | Short-chain-fatty acid irrigation | N/A |

| 63 | F | N/A | Short-chain-fatty acid irrigation | N/A | ||

| 54 | M | N/A | Short-chain-fatty acid irrigation | N/A | ||

| 56 | M | N/A | Short-chain-fatty acid irrigation | N/A | ||

| 8 | Triantafillidis et al[31] | 64 | F | - | 5 aminosalicylic acid enemas comparison with Betamethasone enemas | There were no differences in the degree of clinical improvement, or in the endoscopic and histologic scores seen at the end of the trials, between betamethasone and 5-ASA. |

| 9 | Tripodi et al[43] | 85 | F | - | 5-aminosalicylic acid enemas | Clinically asymptomatic at a 6-mo follow-up. |

| 10 | Lu et al[38] | 45 | F | Intravenous metronidazole | Colectomy of the diverted segment | Without complications and has been doing well postoeratively. |

| 11 | Lai et al[47] | 49 | M | - | Daily 5-ASA suppository and total parenteral nutrition | 6 wk of treatment with 5-ASA, the patient had decreased rectal pain and bleeding. |

| 12 | Lim et al[32] | 60 | F | - | Oral prednisolone, oral mesalazine, and mesalazine enemas | PSL was tapered off over four months and she remained well. |

| 0 | M | Closure of the loop ileostomy→oral prednisolone, oral olsalazine and oral metronidazole→sigmoid loop colostomy | The defunctioned rectosigmoid was partially removed, leaving the lower rectum and anal canal; the loop colostomy was refashioned into an end colostomy→colectomy and removal of residual rectal stump and anal canal was performed and an end ileostomy fashioned | He subsequently made a good recovery and steroid therapy was discontinued. | ||

| 13 | Jowett et al[33] | 75 | F | - | Topical steroid enemas. | UC |

| 14 | Lim et al[35] | 66 | M | - | Steroid enemas | 6 mo later he developed ulcerative colitis. |

| 15 | Kiely et al[36] | 6 | M | PSL and AZA | SCFA | Oral PSL was continued at the reduced rate of 5mg on alternate days until he underwent an uneventful rectal excision and J-pouch anal anastomosis 1 mo later. Two months after this, his ileostomy was closed. |

| 3 | M | Salazopyrine | SCFA | His ileostomy was closed 3 mo later, and he was remained symptom free. | ||

| 8 | F | - | SCFA | Her ulceration was virtually healed and showed a reduction in endoscopic index from 9 to 3. Treatment was maintained until her colostomy was reversed a month later. After stoma closure, SCFAs were discontinued with no further recurrence of symptoms. | ||

| 3 | M | N/A | SCFA | For redo pull-through | ||

| 10 | M | N/A | SCFA | Rectal excision | ||

| 16 | Komuro et al[41] | 46 | M | - | - | The post endoscopic course was uneventful without any treatment. |

| 17 | Tsironi et al[48] | 40 | M | Mesalazine suppository and steroid enemas | Metronidazole suppository | Improved quickly and remains well and asymptomatic 12 wk after treatment. |

| 18 | Boyce et al[37] | 29 | M | - | Completion proctectomy | Completion proctectomy was uneventful and from which the patient made an unremarkable recovery. |

| 19 | Haugen et al[49] | 36 | F | The water and vinegar solution enema, steroid enema, bismuth subsalicylate (standard treatment SCFA enmas was not option due to insurance and spina bifida) | Antegrade irrigations of her distal bowel with tap water | Weekly to twice weekly irrigations completely stopped the malodorous and troublesome discharge. |

| 20 | Talisetti et al[50] | 19 | F | SCFA enema, steroids, metronidazole | Colectomy(entire colon was ultimately resected, Since only 15 cm of jejunum appeared healthy, her mid and distal small bowel was also resected up to 15 cm from the ligament of Treitz) | N/A |

| 21 | Kominami et al[51] | 84 | M | Short-chain fatty acid enema | 5-aminosalicylic acid enemas | Undergoing 5-aminosalicylic acid enemas maintenance therapy. |

| 22 | Watanabe et al[44] | 76 | F | Oral mesalazine, corticosteroid, metronidazole, and ciprofloxacin | Leukocytapheresis, following low dose of metronidazole and ciprofloxacin | After 18 mo, her condition remains stable without the need for medication. |

| 23 | Gundling et al[45] | 75 | F | Enemas containing 5-aminosalicylic acid and steroids and antibiotic therapy | Autologous fecal transplantation | All symptoms improved dramatically within 5 d after the first treatment. Colonoscopy 28 d after the first treatment showed no major signs of inflammation in the colonic stump. |

| 24 | Matsumoto et al[52] | 65 | M | Corticosteroid and mesalazine enemas, prednisolone injections. | A combined mesalazine plus corticosteroid enema | Finally proctectomy and ileal pouch-anal anastomosis were successfully performed. |

| 25 | Custon et al[29] | 44 | M | - | Dextrose( hypertonic glucose ) spray endoscopically | The patient did not experience further episodes of recurrent bleeding during the 6-mo follow-up. No prescribed medicines were given after the endoscopic therapy. |

The basic mechanisms underlying diversion colitis are still unclear. Glotzer hypothesized that it might be the result of bacterial overgrowth, the presence of harmful bacteria, nutritional deficiencies, toxins, or disturbance in the symbiotic relationship between luminal bacteria and the mucosal layer[2]. Reportedly, concentrations of carbohydrate-fermenting anaerobic bacteria and pathogenic bacteria are reduced in de-functioned colons[5,23,53] and these reports indicate that the overgrowth of anaerobic bacteria or a pathogenic bacterium is unlikely to be an important etiological factor. On the other hand, there is an increase of nitrate-reducing bacteria in patients with diversion colitis[7] and nitrate-reducing bacteria produce nitric oxide (NO) which plays a protective role in low concentrations, but at higher levels it becomes toxic to the colonic tissue[54]. Thus, it has been suggested that increases in nitrate-reducing bacteria may result in toxic levels of NO, leading to the diversion colitis.

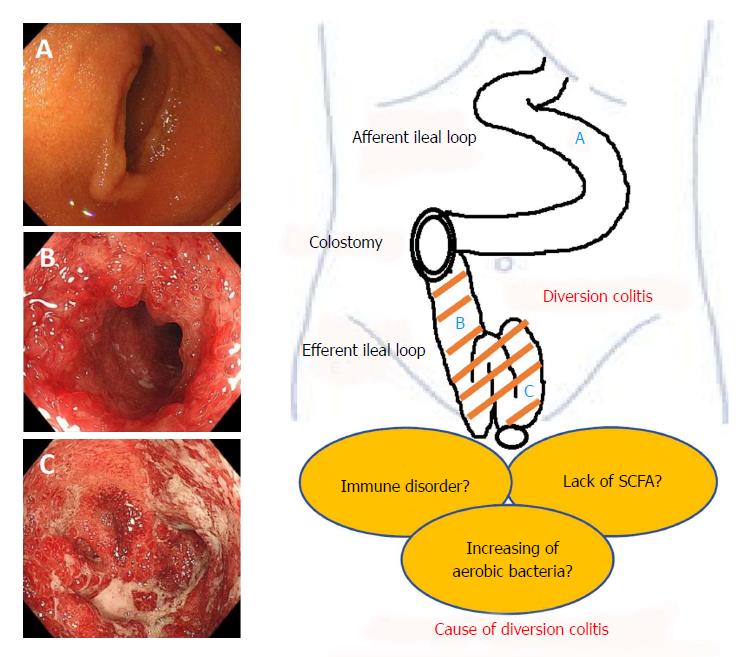

Recently, ischemia has been proposed as a cause of diversion colitis[8]. The explanation surely lies in changes to the luminal flora consequent to fecal stream interruption. Normal luminal bacteria produce SCFA, such as butyric acid. Butyrate is the principal oxidative substrate for colonocytes[55] and patients with diversion colitis may improve following topical treatment with SCFA, especially with butyrate enemas[5,36]. This hypothesis is based on evidence that suggests SCFA relax vascular smooth muscle and that butyrate deficiencies may induce increased tone in the pelvic arteries, therefore leading to relative ischemia of the colorectal mucosa and intestinal wall[5]. It is obvious that additional, basic research is necessary in order to discern disease mechanisms. We have summarized the pathogenesis of this disease entity in Figure 1.

Most patients are asymptomatic[22], however about one third of patients may exhibit symptoms of diversion colitis[2,3,6,9]. Patients generally present with varying symptoms such as abdominal discomfort, tenesmus, anorectal pain, mucous discharge, and rectal bleeding. The most common symptoms include bloody, serous, or mucous discharge in 40% of the population, and abdominal pain and tenesmus in 15% of the population[3]. There have been several reports of severe rectal bleeding[24,29,56]. There is a report of massive rectal distension causing bilateral ureteric obstruction[37] and a case report of diversion colitis causing severe sepsis requiring a colectomy[38]. These symptoms can start within 1 mo to 3 years after surgery[22,24]. Our review also showed that clinical symptoms of rectal bleeding were seen in 25 cases, abdominal pain in 3 cases, anal pain in 3 cases, and sepsis in 1 case[38]. On the other hand, 21 of 46 cases had no symptoms (Table 1), as previously reported[24]. Additionally, in the presence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, the number of symptomatic patients rises to 33% and 87% respectively[53]. Our review showed cases with primary illness of diverticula with perforation (n = 11), fecal incontinence (n = 6), chronic constipation or ileus (n = 5), ulcerative colitis (n = 5), Crohn’s disease (n = 4), carcinoma (n = 3), and various other diseases (Table 1).

Macroscopically, diversion colitis may involve the whole de-functioned colon or isolated segments. These findings include erythema, diffuse granularity, and blurring of vascular pattern in about 90% of the population. It is also associated with mucosal friability (80%) edema (60%), apthous ulceration, and bleeding, to varying degrees[2,3,8-12,39,40]. There is a case report of diversion colitis causing mucosal tears within the defunctioned colon[41]. Recently, Hundorfean et al[57] reported a first description and in vivo diagnosis of diversion colitis after surgery, by virtual chromoendoscopy and fluorescein-guided confocal laser endomicroscopy. Our literature review showed that endoscopic findings were evidenced in 44 out of 46 cases, and severe inflammation with ulceration (endoscopic index ≥ 8) in 17 cases.

The pathological finding of diversion colitis and pouchitis usually vary with degree of severity, therefore, no specific microscopic findings have been noted. The histological features of diversion colitis can mimic those of IBD, even when a pre-existing IBD has not been documented[10,11,13-15]. The most notable feature often seen in diversion colitis is lymphoid follicular hyperplasia[9,14,58]. Atrophy, crypt branching, mucin depletion, crypt distortion, regenerative hyperplasia, paneth cell metaplasia, thickening of muscularis mucosa, diffuse active mucosal inflammation with crypt abscesses, ulceration, and vacuolar and epithelial degeneration along with features of chronic inflammation (usually confined to the mucosa) are seen with varying degrees of severity[9-12,14,16,17,59]. More recently, features of ischemia, such as superficial coagulative necrosis and fibrosis, have been described[8]. Our review showed that 37 out of 46 cases exhibited pathological findings including 15 cases of crypt abscess or cryptitis[2], and 14 cases of lymphoid follicular hyperplasia (which was not previously identified as a feature of diversion colitis). These features are non-specific and, to date, no characteristic feature or features of diversion colitis have been identified.

Because of the small number of patients and the unknown etiology, there is no established standard therapy for diversion colitis and pouchitis. Szczepkowski et al[4] proposed a management strategy for patients with de-functioned distal stomas. He divided patients with diversion colitis into three groups based on a study of 145 patients. These groups consisted of Group 1 (no clinical, morphological or endoscopic evidence of diversion colitis), Group 2, (mild or moderate signs of diversion colitis), and Group 3 (severe diversion colitis). Group 1 can be treated conservatively, Group 2 can be treated using conservative management prior to restoration of colonic continuity and Group 3 should ideally undergo restoration of colonic continuity. If a surgical option is not feasible, pharmacologic treatment options should be tried to resolve the inflammation. A summary of the clinical courses of case reports is shown in Table 2.

Treatment of diversion colitis should be primarily directed at restoring bowel continuity to restore the luminal flow. This will resolve the symptoms and assist the bowel to return to normal. Re-anastomosis has proven to be consistently effective in halting the symptoms of diversion colitis in a number of studies[2,10,25,39,42]. Re-anastomosis of diverted segments in patients with preexisting inflammatory bowel disease is a more difficult decision because inflammation in the diverted segment could represent inflammatory bowel disease or diversion colitis, each of which dictate different courses of action[3,21,42]. Resection is not typically required. Indications for resection include uncontrolled perianal sepsis, perianal fistulous disease, anal incontinence, and uncontrolled symptoms related to diversion colitis.

Nutritional imbalance in the excluded colon is likely responsible for the pathologic changes and symptoms of diversion colitis. However, current evidence does not support the effectiveness of lifestyle modifications or nutritional imbalance[60].

Pharmacologic treatment is generally indicated for the temporary control of symptoms in preparation for surgery. It is used occasionally for patients who are not considered surgical candidates because of severe medical comorbidities, poor sphincter function, or reasons of technical difficulty.

Short-chain fatty acids, mainly butyrate, are the major fuel source for the epithelium. Their absence in the diverted tract may produce mucosal atrophy and inflammation. Bacteria produce SCFAs as byproducts of carbohydrate fermentation in the colonic lumen, and SCFAs provide the primary energy source for colonic mucosal cells[13]. In human neutrophils, SCFAs reduce the production of reactive oxygen species, which are the agents of oxidative tissue damage[61]. Treatment of diversion colitis with SCFA or butyrate has shown inconsistent results. Harig successfully improved symptoms and endoscopic inflammatory change by SCFA[5]. Komorowski et al[10] reported similar results in four patients with diversion colitis with SCFA irrigation. However, Guillmot et al[16,28]. failed to demonstrate either histological or endoscopic improvement The differences in response may be partially accounted for by disease groupings. In recent years, several studies on the usefulness of SCFA, including of butyrate, are reported[19,62]. Cristina et al[27] proposed that butyrate enemas may prevent the atrophy of the diverted colon/rectum, thus improving the recovery of tissue integrity.

Usefulness of 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) enemas in diversion colitis was reported for the first time by Triantafillidis et al[31] in 1991. Tripodi et al[43] has also reported similar results in 1992. Caltabiano et al[63] reported that 5-ASA enema reduces oxidative DNA damage in colonic mucosa and reduces mucosal damage using rats in a diversion colitis model. It is considered that the mucosal disorder may be improved by protective action against oxidative DNA damage and the anti-inflammatory action of 5ASA[64].

Glotzer reported on several patients with diversion colitis treated by steroid enemas in 1984[2]. Lim and Jowett also reported the efficacy of the steroid enemas in 2000[32,33]. Corticosteroids are first-line agents for symptomatic diversion colitis, with varying effectiveness.

Resolution of diversion colitis, based on endoscopic and histologic examination, has been reported following irrigation of the diverted segment of the colon with fibers[65,66]. Joaquim et al[66] investigated the effect of irrigating the colorectal mucosa of patients with a colostomy using a solution of fibers. In 11 patients with loop colostomies, the diverted colorectal segment was irrigated with a solution containing 5% fibers (10 g/d) for 7 d. Irrigation with fibers improves inflammation within the defunctionalized colon, so this therapy may play a role in the preoperative management of colostomies, potentially decreasing the high incidence of diarrhea after reestablishment of the intestinal transit.

Watanabe et al[44] reported successful treatment of leukocytapheresis in a patient with chronic antibiotic-refractory diversion pouchitis following IPAA for UC with diverting ileostomy. The mucosa of the diverted pouch is less exposed to the fecal stream and pathogens. Therefore, altered immunity likely plays a major role in the maintenance of diversion pouchitis. Leukocytapheresis to address the altered immunity would seem a reasonable approach for antibiotic-refractory pouchitis following IPAA for UC with diverting ileostomy, and its effectiveness in the case suggests that altered immunity may be a key contributing factor compared with dysbiosis, bacterial pathogens, and ischemia.

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), which consists of transferring stool from a healthy donor to the patient’s colon, is an effective treatment for some diseases of the colon such as Crohn’s disease and recurrent Clostridium difficile infections[67]. Gundling et al[45] presented that autologous FMT might be an effective and safe option for relapsing DC after standard therapies have failed. Since the interruption of the fecal stream is central to the development of DC, FMT seems to be a hopeful treatment.

Custon et al[29] presented a patient with ulcerative colitis with severe hematochezia and diffuse mucosal bleeding in a diverted ileal pouch, which was successfully treated with endoscopic spray of hypertonic glucose (50% dextrose). Hypertonic glucose may work thorough osmotic dehydration and sclerosant effects, inducing long-term mural necrosis and fibrotic obliteration of mucosal vessels[68,69]. Glucose spray is safe and inexpensive, and it carries a very low risk of complications. The approach has the potential to reduce recurrent bleeding and need for surgical interventions.

The goal of treatment is the reduction or elimination of symptoms. Patients who desire stoma closure and have acceptable risks should undergo surgery to re-establish intestinal continuity. In their prospective study, Son et al[20] reported that the severity of DC is related to diarrhea after an ileostomy reversal and may adversely affect quality of life. Pharmacologic treatments are needed for symptomatic patients with permanent stomas and patients who are unable to undergo stoma closure for reasons of technical difficulty, poor anal sphincter function, or persistent perianal sepsis. In our review, SCFA[5,10,18,19,26,27,36,62], 5-ASA enemas[31,43,47,51], steroid enemas[21,32,33], and irrigation with fibers[65,66] have been tried with various efficacies for mucosal inflammation. Only case reports of therapy involving leukocytapheresis[44], autologous fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT)[45] and dextrose (hypertonic glucose) spray[29] have been tried with some effect. We have summarized the method, advantages and disadvantages of each pharmacologic treatment in Table 3.

| Treatment | Ref. | Procedure/standard dosage | Efficacy | Complications/main side effects |

| Surgical anastomosis | [2,3,10,21,25,39,42] | Mobilization of both ends of the bowel with either sutured or stapled anastomosis. | The most effective method of eliminating the signs and symptoms | Bleeding, infection, anastomotic leak, anastomotic stricture, anesthetic risks |

| Corticosteroids | [2,32,33] | Hydrocortisone (100 mg per 60 mL bottle) enema is administered once daily for up to 3 wk. | Response to treatment is generally seen in 3 to 5 d. | Local pain and burning, occasionally rectal bleeding. |

| Occasional treatment may be given for 2 to 3 mo depending on clinical response. | Prolonged treatment may result in systemic absorption, causing systemic side effects. | |||

| 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) enemas | [31,43,63,64] | 4 g of mesalazine in 60 mL suspensions, administered rectally once-daily dose for 4 to 5 wk. | Varying effect | Occasionally produces acute intolerance manifested by cramping, acute abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea, fever, headache, and rash. |

| Short-chain-fatty acid (SCFA) | [5,10,13,18,19,26,27,61,62] | SCFA enema rectally twice a day for 2 wk, and then tapered according to response over 2 to 4 wk. | Varying effect | None |

| Irrigation with Fibers | [65,66] | Solution containing 5% fibers (10 g/d) for 7 d. | The endoscopic score which is used to quantify the intensity of the inflammation at the mucosa at the diverted colon diminished after treatment. | Probably none |

| Leukocytapheresis | [44] | Leukocytapheresis, at flow rate of 40 mL/min for 60 min, once weekly for 5 wk, following low dose of metronidazole and ciprofloxacin, another set of weekly leukocytapheresis was added. | Significant improvement in her pouchitis disease activity index (PDAI) from 14 to 1. | The common side effects were nausea, vomiting, fever, chills, and nasal obstruction. |

| Autologous fecal transplantation | [45] | Feces were collected from the colostomy bag, diluted with 600 ml of sterile saline (0.9 %), stirred and filtered three times using an ordinary coffee filter, irrigation endoscopically. This procedure was repeated 3 times within 4 wk (on day 0, day 10 and day 28). | All symptoms improved dramatically within 5 d after the first treatment. Colonoscopy 28 d after the first treatment showed no major signs of inflammation in the colonic stump | None, patient's tolerance required. |

| Dextrose spray (hypertonic glucose) | [29] | Endoscopically sprayed with 150 mL 50% dextrose via a catheter. | Follow-up pouchoscopy 2 wk after the dextrose spray showed normal pouch mucosa with no evidence of bleeding or mucosal friability. | It has a very low chance of causing transient hyperglycemia because there is no direct injection of the hypertonic solution into blood vessels. |

The vast majority of diverted patients remain asymptomatic, however diversion colitis occurs in almost all diverted patients. It generally resolves following colostomy closure. However, those patients with significant symptoms or histories of colitis or diarrhea should undergo a complete proximal and distal colonic evaluation prior to stoma closure, and some treatments need not be delayed in these patients. Patients with permanent diversions should undergo periodic pharmacologic treatment. This review of various treatments for diversion colitis will hopefully be useful for determining future treatments.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: De Silva AP, Triantafillidis JK, Tandon RK S- Editor: Wang XJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | Morson BC, Dawson IMP. Gastrointestinal Pathology, first ed., Blackwellfic Publications, London. 1972;. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Glotzer DJ, Glick ME, Goldman H. Proctitis and colitis following diversion of the fecal stream. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:438-441. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Mudretsova-Viss KA, Gabriél’iants GM. [Enterococcal survival in forcemeat preserved in polymer films and in cutlets made from it]. Vopr Pitan. 1975;1:68-72. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Ma CK, Gottlieb C, Haas PA. Diversion colitis: a clinicopathologic study of 21 cases. Hum Pathol. 1990;21:429-436. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Harig JM, Soergel KH, Komorowski RA, Wood CM. Treatment of diversion colitis with short-chain-fatty acid irrigation. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:23-28. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 596] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 508] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Frisbie JH, Ahmed N, Hirano I, Klein MA, Soybel DI. Diversion colitis in patients with myelopathy: clinical, endoscopic, and histopathological findings. J Spinal Cord Med. 2000;23:142-149. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Neut C, Guillemot F, Colombel JF. Nitrate-reducing bacteria in diversion colitis: a clue to inflammation? Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:2577-2580. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Villanacci V, Talbot IC, Rossi E, Bassotti G. Ischaemia: a pathogenetic clue in diversion colitis? Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:601-605. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Roe AM, Warren BF, Brodribb AJ, Brown C. Diversion colitis and involution of the defunctioned anorectum. Gut. 1993;34:382-385. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Komorowski RA. Histologic spectrum of diversion colitis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14:548-554. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Geraghty JM, Talbot IC. Diversion colitis: histological features in the colon and rectum after defunctioning colostomy. Gut. 1991;32:1020-1023. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Winslet MC, Poxon V, Youngs DJ, Thompson H, Keighley MR. A pathophysiologic study of diversion proctitis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1993;177:57-61. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Murray FE, O’Brien MJ, Birkett DH, Kennedy SM, LaMont JT. Diversion colitis. Pathologic findings in a resected sigmoid colon and rectum. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:1404-1408. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Yeong ML, Bethwaite PB, Prasad J, Isbister WH. Lymphoid follicular hyperplasia--a distinctive feature of diversion colitis. Histopathology. 1991;19:55-61. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Asplund S, Gramlich T, Fazio V, Petras R. Histologic changes in defunctioned rectums in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a clinicopathologic study of 82 patients with long-term follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1206-1213. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Haque S, West AB. Diversion colitis--20 years a-growing. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;15:281-283. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Vujanić GM, Dojcinov SD. Diversion colitis in children: an iatrogenic appendix vermiformis? Histopathology. 2000;36:41-46. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Neut C, Guillemot F, Gower-Rousseau C, Biron N, Cortot A, Colombel JF. [Treatment of diversion colitis with short-chain fatty acids. Bacteriological study]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1995;19:871-875. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Pal K, Tinalal S, Al Buainain H, Singh VP. Diversion proctocolitis and response to treatment with short-chain fatty acids--a clinicopathological study in children. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2015;34:292-299. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Son DN, Choi DJ, Woo SU, Kim J, Keom BR, Kim CH, Baek SJ, Kim SH. Relationship between diversion colitis and quality of life in rectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:542-549. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Korelitz BI, Cheskin LJ, Sohn N, Sommers SC. The fate of the rectal segment after diversion of the fecal stream in Crohn’s disease: its implications for surgical management. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1985;7:37-43. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Ferguson CM, Siegel RJ. A prospective evaluation of diversion colitis. Am Surg. 1991;57:46-49. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Baek SJ, Kim SH, Lee CK, Roh KH, Keum B, Kim CH, Kim J. Relationship between the severity of diversion colitis and the composition of colonic bacteria: a prospective study. Gut Liver. 2014;8:170-176. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Whelan RL, Abramson D, Kim DS, Hashmi HF. Diversion colitis. A prospective study. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:19-24. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Orsay CP, Kim DO, Pearl RK, Abcarian H. Diversion colitis in patients scheduled for colostomy closure. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:366-367. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Guillemot F, Colombel JF, Neut C, Verplanck N, Lecomte M, Romond C, Paris JC, Cortot A. Treatment of diversion colitis by short-chain fatty acids. Prospective and double-blind study. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:861-864. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Luceri C, Femia AP, Fazi M, Di Martino C, Zolfanelli F, Dolara P, Tonelli F. Effect of butyrate enemas on gene expression profiles and endoscopic/histopathological scores of diverted colorectal mucosa: A randomized trial. Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48:27-33. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 65] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Fazio VW, Ziv Y, Church JM, Oakley JR, Lavery IC, Milsom JW, Schroeder TK. Ileal pouch-anal anastomoses complications and function in 1005 patients. Ann Surg. 1995;222:120-127. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Nyabanga CT, Shen B. Endoscopic Treatment of Bleeding Diversion Pouchitis with High-Concentration Dextrose Spray. ACG Case Rep J. 2017;4:e51. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Gorgun E, Remzi FH. Complications of ileoanal pouches. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2004;17:43-55. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 50] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 31. | Triantafillidis JK, Nicolakis D, Mountaneas G, Pomonis E. Treatment of diversion colitis with 5-aminosalicylic acid enemas: comparison with betamethasone enemas. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:1552-1553. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 32. | Lim AG, Langmead FL, Feakins RM, Rampton DS. Diversion colitis: a trigger for ulcerative colitis in the in-stream colon? Gut. 1999;44:279-282. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 33. | Jowett SL, Cobden I. Diversion colitis as a trigger for ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2000;46:294. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | Burman JH, Thompson H, Cooke WT, Williams JA. The effects of diversion of intestinal contents on the progress of Crohn’s disease of the large bowel. Gut. 1971;12:11-15. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 35. | Lim AG, Lim W. Diversion colitis: a trigger for ulcerative colitis in the instream colon. Gut. 2000;46:441. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 36. | Kiely EM, Ajayi NA, Wheeler RA, Malone M. Diversion procto-colitis: response to treatment with short-chain fatty acids. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:1514-1517. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Boyce SA, Hendry WS. Diversion colitis presenting with massive rectal distension and bilateral ureteric obstruction. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:1143-1144. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Lu ES, Lin T, Harms BL, Gaumnitz EA, Singaram C. A severe case of diversion colitis with large ulcerations. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1508-1510. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 39. | Lusk LB, Reichen J, Levine JS. Aphthous ulceration in diversion colitis. Clinical implications. Gastroenterology. 1984;87:1171-1173. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 40. | Ona FV, Boger JN. Rectal bleeding due to diversion colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1985;80:40-41. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 41. | Komuro Y, Watanabe T, Hata K, Nagawa H. Diversion colitis with a mucosal tear on endoscopic insufflation. Gut. 2003;52:1388-1389. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 42. | Korelitz BI, Cheskin LJ, Sohn N, Sommers SC. Proctitis after fecal diversion in Crohn’s disease and its elimination with reanastomosis: implications for surgical management. Report of four cases. Gastroenterology. 1984;87:710-713. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 43. | Tripodi J, Gorcey S, Burakoff R. A case of diversion colitis treated with 5-aminosalicylic acid enemas. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:645-647. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 44. | Watanabe C, Hokari R, Miura S. Chronic antibiotic-refractory diversion pouchitis successfully treated with leukocyteapheresis. Ther Apher Dial. 2014;18:644-645. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Gundling F, Tiller M, Agha A, Schepp W, Iesalnieks I. Successful autologous fecal transplantation for chronic diversion colitis. Tech Coloproctol. 2015;19:51-52. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Scott RL, Pinstein ML. Diversion colitis demonstrated by double-contrast barium enema. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;143:767-768. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Lai JM, Chuang TY, Francisco GE, Strayer JR. Diversion colitis: a cause of abdominal discomfort in spinal cord injury patients with colostomy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78:670-671. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 48. | Tsironi E, Irving PM, Feakins RM, Rampton DS. “Diversion” colitis caused by Clostridium difficile infection: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1074-1077. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Haugen V, Rothenberger DA, Powell J. Antegrade irrigations of a surgically reconstructed Hartmann’s pouch to treat intractable diversion colitis. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2008;35:231-232. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Talisetti A, Longacre T, Pai RK, Kerner J. Diversion colitis in a 19-year-old female with megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:2338-2340. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Kominami Y, Ohe H, Kobayashi S, Higashi R, Uchida D, Morimoto Y, Nakarai A, Numata N, Hirao K, Ogawa T. [Classification of the bleeding pattern in colonic diverticulum is useful to predict the risk of bleeding or re-bleeding after endoscopic treatment]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2012;109:393-399. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 52. | Matsumoto S, Mashima H. Efficacy of Combined Mesalazine Plus Corticosteroid Enemas for Diversion Colitis after Subtotal Colectomy for Ulcerative Colitis. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2016;10:157-160. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Neut C, Colombel JF, Guillemot F, Cortot A, Gower P, Quandalle P, Ribet M, Romond C, Paris JC. Impaired bacterial flora in human excluded colon. Gut. 1989;30:1094-1098. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 54. | McCafferty DM, Mudgett JS, Swain MG, Kubes P. Inducible nitric oxide synthase plays a critical role in resolving intestinal inflammation. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1022-1027. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 55. | Velázquez OC, Lederer HM, Rombeau JL. Butyrate and the colonocyte. Production, absorption, metabolism, and therapeutic implications. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;427:123-134. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 56. | Bosshardt RT, Abel ME. Proctitis following fecal diversion. Dis Colon Rectum. 1984;27:605-607. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 57. | Hundorfean G, Chiriac MT, Siebler J, Neurath MF, Mudter J. Confocal laser endomicroscopy for the diagnosis of diversion colitis. Endoscopy. 2012;44 Suppl 2 UCTN:E358-E359. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Lechner GL, Frank W, Jantsch H, Pichler W, Hall DA, Waneck R, Wunderlich M. Lymphoid follicular hyperplasia in excluded colonic segments: a radiologic sign of diversion colitis. Radiology. 1990;176:135-136. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Edwards CM, George B, Warren B. Diversion colitis--new light through old windows. Histopathology. 1999;34:1-5. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 60. | Eggenberger JC, Farid A. Diversion Colitis. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2001;4:255-259. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 61. | Liu Q, Shimoyama T, Suzuki K, Umeda T, Nakaji S, Sugawara K. Effect of sodium butyrate on reactive oxygen species generation by human neutrophils. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:744-750. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 62. | Schauber J, Bark T, Jaramillo E, Katouli M, Sandstedt B, Svenberg T. Local short-chain fatty acids supplementation without beneficial effect on inflammation in excluded rectum. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:184-189. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 63. | Caltabiano C, Máximo FR, Spadari AP, da Conceição Miranda DD, Serra MM, Ribeiro ML, Martinez CA. 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) can reduce levels of oxidative DNA damage in cells of colonic mucosa with and without fecal stream. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:1037-1046. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Grisham MB, Granger DN. Neutrophil-mediated mucosal injury. Role of reactive oxygen metabolites. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:6S-15S. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 65. | Agarwal VP, Schimmel EM. Diversion colitis: a nutritional deficiency syndrome? Nutr Rev. 1989;47:257-261. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 66. | de Oliveira-Neto JP, de Aguilar-Nascimento JE. Intraluminal irrigation with fibers improves mucosal inflammation and atrophy in diversion colitis. Nutrition. 2004;20:197-199. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | van Nood E, Vrieze A, Nieuwdorp M, Fuentes S, Zoetendal EG, de Vos WM, Visser CE, Kuijper EJ, Bartelsman JF, Tijssen JG. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:407-415. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2582] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2489] [Article Influence: 226.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Chang KY, Wu CS, Chen PC. Prospective, randomized trial of hypertonic glucose water and sodium tetradecyl sulfate for gastric variceal bleeding in patients with advanced liver cirrhosis. Endoscopy. 1996;28:481-486. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Tian C, Mehta P, Shen B. Endoscopic Therapy of Bleeding from Radiation Enteritis with Hypertonic Glucose Spray. ACG Case Rep J. 2014;1:181-183. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |