Published online Feb 7, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i5.869

Peer-review started: September 18, 2016

First decision: October 20, 2016

Revised: November 6, 2016

Accepted: December 8, 2016

Article in press: December 8, 2016

Published online: February 7, 2017

To investigate factors, including psychosocial factors, associated with alcoholic use relapse after liver transplantation (LT) for alcoholic liver disease (ALD).

The clinical records of 102 patients with ALD who were referred to Nagoya University Hospital for LT between May 2003 and March 2015 were retrospectively evaluated. History of alcohol intake was obtained from their clinical records and scored according to the High-Risk Alcoholism Relapse scale, which includes duration of heavy drinking, types and amount of alcohol usually consumed, and previous inpatient treatment history for alcoholism. All patients were assessed for eligibility for LT according to comprehensive criteria, including Child-Pugh score, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score, and psychosocial criteria.

Of the 102 patients with ALD referred for LT, seven (6.9%) underwent LT. One (14.3%) of these seven patients returned to heavy drinking, but that patient was able to successfully quit drinking following an immediate intervention, consisting of psychotherapeutic education and supportive psychotherapy, by a psychiatrist. A comparison between the transplantation/registration (T/R) group, consisting of the seven patients who underwent LT and 10 patients listed for deceased donor LT, and 50 patients who did not undergo LT and were not listed for deceased donor LT (non-T/R group), showed statistically significant differences in duration of abstinence period (P < 0.01), duration of heavy drinking (P < 0.05), adherence to medical treatment (P < 0.01), and declaration of abstinence (P < 0.05).

Patients with ALD referred for LT require comprehensive evaluation, including evaluation of psychosocial criteria, to prevent alcoholic recidivism.

Core tip: Although alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is the second most common indication for liver transplantation (LT), post-transplant relapse of alcohol use can have a negative impact on patient outcomes. It is therefore important to preoperatively assess the risk of post-transplant alcohol use. To date, however, psychosocial evaluation criteria of LT for ALD have not been established, indicating a real need for useful criteria to assess the risks of post-transplant alcohol use. This study describes a set of psychosocial evaluation criteria that may be useful in assessing the risk of relapse in patients who undergo LT for ALD.

- Citation: Onishi Y, Kimura H, Hori T, Kishi S, Kamei H, Kurata N, Tsuboi C, Yamaguchi N, Takahashi M, Sunada S, Hirano M, Fujishiro H, Okada T, Ishigami M, Goto H, Ozaki N, Ogura Y. Risk of alcohol use relapse after liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(5): 869-875

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i5/869.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i5.869

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is one of the most common causes of advanced liver cirrhosis and has become the second most common indication for liver transplantation (LT), after cirrhosis caused by viral hepatitis[1]. However, 20%-30% of patients who undergo LT for ALD will return to heavy drinking after LT[2]. Post-transplant relapse of alcohol use is extremely crucial, because alcoholic recidivism has a negative impact on post-transplant compliance and long-term outcomes of LT recipients[3]. Post-transplant relapse of alcohol use has been associated with increased damage to transplanted liver allografts[4,5] and may be associated with reduced survival after LT[3,6,7]. Thus, in evaluating candidates for LT, it is crucial to preoperatively predict and precisely assess the risk of post-transplant relapse of alcohol use in patients with ALD[8].

Various criteria and screening procedures have been reported to predict relapsed alcohol use[8]. Most transplant centers worldwide require a minimum of 6 mo of alcohol abstinence prior to LT. Patients who can maintain this 6-mo abstinence have been reported to be at lower risk of alcohol use relapse than those who are abstinent for less than 6 mo[9,10]. However, a method for selecting LT candidates based on the 6-mo rule alone has been criticized, because this method does not account for other factors that may influence alcoholic behavior[5,11,12]. Unlike physical evaluation criteria, psychosocial criteria evaluating the suitability of LT for patients with ALD have not yet been determined, because highly valid and reliable psychosocial criteria are more difficult to establish. There is therefore a real need for useful criteria to assess the risks of post-transplant relapse of alcohol use beforehand. This study was therefore performed to comprehensively investigate factors, including psychosocial factors, associated with alcoholic use relapse after LT for ALD. Based on these findings, we propose and present a set of psychosocial evaluation criteria that may be useful in assessing relapse risk in patients with ALD who are candidates for LT, and provide a framework that can be of use clinically.

At Nagoya University Hospital, approximately 20 LTs are performed annually. A transplantation medical team, consisting of transplant surgeons, gastroenterologists, hepatologists, psychiatrists, transplant coordinators, and psychologists, was launched in 2004, and the team continues to hold interdisciplinary conferences at least once weekly[13]. Patients were treated by psychiatrists, if necessary. However, in our institution, the psychiatry and self-help groups work in a coordinated manner. Our style is a so-called “team medicine”.

Between May 2003 and March 2015, 102 patients with ALD were referred to Nagoya University Hospital for LT. A definitive diagnosis of ALD was based on a history of habitual and excessive alcohol consumption. The clinical records of these patients were retrospectively reviewed. Pre-transplant levels of alcohol consumption were assessed using the High-Risk Alcoholism Relapse (HRAR) scale, which was developed from a study of relapse following inpatient treatment for alcoholism of a cohort of male US veterans[14]. This scale includes three items: duration of heavy drinking, usual number of drinks per day, and number of previous inpatient admissions for treatment of alcoholism[15,16]. Each item is scored 0, 1, or 2, resulting in total possible scores ranging from 0 to 6; high scores, ranging from 3 to 6, have been found to correlate positively with the risk of relapse.

The psychosocial evaluation criteria for LT candidates with ALD are shown in Table 1. Patients with ALD psychosocially considered likely candidates for LT were those at lower risk of alcohol relapse. Alcohol relapse after LT was based on interviews with patients and/or family members.

| Criteria A |

| Abstinence period lasting at least 6 mo |

| An oath of the abstinence from alcoholic drinking for the future |

| Patients with alcoholic liver disease are needed to fulfill the criteria A. |

| Criteria B |

| No presence of psychiatric comorbidity except alcohol-related mental disease |

| A dherence of medical treatment |

| Understanding and agreement of transplant and a support by the family |

| Being at work or ready to work |

| The high-risk alcoholism relapse scale can be scored 0, 1, or 2 |

| Criteria C |

| Re-evaluation one month later in case who is difficult to evaluate risk of alcohol use relapse in the initial interview |

Sixty-seven patients with ALD were evaluated medically for LT by members of the Departments of Transplantation Surgery and/or Gastroenterological Medicine, and were evaluated psychosocially by members of the Department of Psychiatry. Medical factors evaluated included hepatic encephalopathy, ascites, serum concentrations of bilirubin and albumin, international normalized ratio of prothrombin time, plasma creatinine concentration, Model for End-stage Liver Disease score and Child-Pugh score. Alcohol-associated criteria included duration of heavy drinking, adherence to medical treatment, employment or willingness to work, understanding and agreeing to LT, support from family members, occurrence of psychiatric comorbidities except for alcohol-related mental disease, usual number of daily drinks, and HRAR score. The mean follow-up period after LT was 5.1 years.

To present the alcohol drinking, we used the unit of a standard drink in Japan contained 10 g of alcohol, in this study.

Continuous variables were compared by Student’s t-tests and categorical variables by Fisher’s exact test. A P value < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine (Approved No. 15), which waived the requirement for informed consent due to the retrospective design of this study. This study was fully supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C, No. 24591875) from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, and by a grant from the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science.

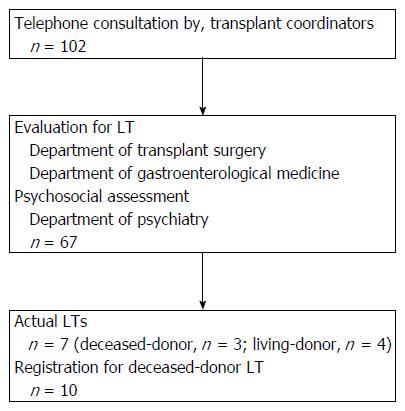

The 102 ALD patients referred to our center for possible LT were evaluated by telephone interviews with our transplant coordinators. Of these patients, 67 (65.6%) underwent both LT evaluation and psychosocial assessment (Table 2), and seven (6.9%) underwent LT (Table 3 and Figure 1). In addition, 10 patients (9.8%) were registered by the Japan Organ Transplant Network as candidates for deceased donor LT. Of the seven patients who met our criteria and underwent LT, six did not return to alcohol drinking after LT, whereas one did (Patient No. 4 in Table 3). This patient met both our medical and psychosocial criteria. He had no psychiatric comorbidity except for alcohol-related mental disease; he adhered to medical treatment, understood and agreed to undergo LT, had support from his family, was employed, and had a score of 2 on the HRAR scale. Therefore, it was difficult to predict his alcohol relapse preoperatively. Interestingly, however, this patient completely quit alcohol following an immediate intervention by psychiatrists, consisting of psychological education and supportive psychotherapy.

| Mean | Range or standard deviation | No./No. responded | Percentage | |||

| Age1 (yr) | 50.2 | 28-69 | Adherence of medical treatment | Present | 45/67 | 67 |

| Gender2 (male/female) | 48/19 | Absent | 20/67 | 30 | ||

| Hepatic encephalopathy2 (point) | 1.2 | 0.4 | Unknown | 2/67 | 3 | |

| Ascites2 (point) | 2.0 | 0.8 | Being at work or ready to work | Present | 47/67 | 70 |

| Bilirubin2 (mg/dL) | 6.1 | 6.0 | Absent | 18/67 | 27 | |

| Albumin2 (g/dL) | 2.8 | 0.5 | Unknown | 2/67 | 3 | |

| International normalized ratio of prothrombin time2 | 1.83 | 0.7 | Understanding and agreement of transplant and a support by the family | Present | 61/67 | 91 |

| Creatinine2 (mg/dL) | 0.9 | 0.6 | Absent | 6/67 | 9 | |

| Model for end-stage liver disease score2 (point) | 1.9 | 7.0 | Presence of psychiatric comorbidity except alcohol-related mental disease | Present | 2/67 | 3 |

| Child-Pugh score2 (point) | 10.1 | 2.0 | Absent | 65/67 | 97 | |

| Duration of heavy drinking2 (yr) | 21.7 | 10.4 | Declaration of abstinence | Present | 55/67 | 82 |

| Usual number of daily drinks2 (L) | 2.1 | 0.8 | Absent | 12/67 | 18 | |

| The HRAR scale2 (point) | 2.3 | 1.0 | Psychiatric hospitalizations | Present | 1/67 | 1 |

| Prothrombin time2 (%) | 34.3 | 16.4 | Absent | 66/67 | 99 | |

| Abstinence period2 (mo) | 12.1 | 15.8 |

| Case | Age at the first drinking | Age at the first examination | Age at the LT | Gender | Comorbidity | Daily intake of alcohol1 | LT | Follow-up (yr) | Alcohol relapse | Self-help groups |

| 1 | 24 | 32 | 36 | Male | None | 17.6 | Deceased-donor | 8.3 | None | None |

| 2 | 27 | 38 | 38 | Female | None | 6.5 | Deceased-donor | 9.9 | None | None |

| 3 | 15 | 42 | 44 | Male | Non-BNon-CLiver cirrhosis | 16.0 | Deceased-donor | 7.3 | None | Participation (spouse only) |

| 4 | 17 | 44 | 46 | Male | Liver cirrhosis (type C) | 20.0 | Deceased-donor | 4.8 | Relapse2 (3 yr after) | None |

| 5 | 13 | 28 | 28 | Male | None | 20.0 | Living-donor (relation: father) | 3.3 | None | Participation |

| 6 | 17 | 51 | 51 | Female | Liver cirrhosis (type C)Hepatocellular carcinoma | 15.0 | Living-donor (relation: daughter) | 1.3 | None | None |

| 7 | 9 | 46 | 46 | Female | None | 20.0 | Living-donor (relation: younger brother) | 0.5 | None | None |

Data from the seven patients who underwent LT and the 10, who were listed for deceased donor LT, defined as the transplantation/registration (T/R) group, were compared with the data of the 50 patients who did not undergo LT and were not listed for deceased donor LT, defined as the non-T/R group (Table 4). The abstinence period was significantly longer (P < 0.01), while the duration of heavy drinking was significantly shorter (P < 0.05), in the T/R group than in the non-T/R group. In addition, the adherence to medical treatment (P < 0.01), and the declaration of abstinence (P < 0.05) were better in the T/R group than in the non-T/R group (Table 4).

| T/R group (n = 17) | Non-T/R group (n = 50) | t-statistic | Degree of freedom | Statistical significance | T/R group (n = 17) | Non-T/R group (n = 50) | Statistical significance | |||||

| Mean (range or SD) | Mean (range or SD) | No/no responded (percentage) | No/no responded (percentage) | |||||||||

| Age1 (yr) | 45.5 (28-62) | 51.8 (31-69) | Adherence of medical treatment | Present | 17/17 | (100) | 28/50 | (56) | P < 0.01 | |||

| Gender (male/female) | 11/6 | 37/13 | Absent | 0/17 | (0) | 20/50 | (40) | |||||

| Abstinence period2 (mo) | 21.2 (17.4) | 8.8 (13.6) | 2.84 | 59 | P < 0.01 | Unknown | 0/17 | (0) | 2/50 | (4) | ||

| Amount of drinking2 (point) | 2.3 (0.7) | 2.1 (0.8) | 1.14 | 58 | NS | Being at work or ready to work | Present | 15/17 | (88) | 32/50 | (64) | NS |

| Duration of heavy drinking2 (yr) | 16.4 (7.5) | 23.8 (10.5) | 2.62 | 58 | P < 0.05 | Absent | 2/17 | (12) | 16/50 | (32) | ||

| Unknown | 0/17 | (0) | 2/50 | (4) | ||||||||

| Understanding and agreement of transplant and a support by the family | Present | 16/17 | (94) | 45/50 | (90) | NS | ||||||

| Absent | 1/17 | (6) | 5/50 | (10) | ||||||||

| Presence of psychiatric comorbidity except alcohol-related mental disease | Present | 0/17 | (0) | 2/50 | (4) | NS | ||||||

| Absent | 17/17 | (100) | 48/50 | (96) | ||||||||

| Declaration of abstinence | Present | 17/17 | (100) | 38/50 | (76) | P < 0.05 | ||||||

| Absent | 0/17 | (0) | 12/50 | (24) | ||||||||

| Psychiatric hospitalizations | Present | 1/67 | (6) | 0/50 | (0) | NS | ||||||

| Absent | 16/67 | (94) | 50/50 | (100) | ||||||||

Although our comprehensive LT criteria for ALD seemed to be effective, we encountered one thought-provoking case. The patient was a 44-year-old man, married at age 23 years and with two children. He inherited a business from his father and was essentially self-employed. Because of overwork, he started drinking heavily at age 30 years. Although his family was aware of his drinking problem, he denied his drinking. He got divorced at age 37 years and lost his son in a traffic accident at age 40 years, after which he began drinking more heavily. At age 41 years, his family doctor warned him that he would die in the near future if he did not stop drinking. Although he stopped drinking immediately, his liver condition worsened and he required LT. Following psychosocial evaluation, he was registered for deceased donor LT. After being on the waiting list for 3 years, he underwent a deceased donor LT. During follow-up after LT, his transplant surgeons suspected that he might have returned to heavy drinking. Because he admitted that he had actually returned to heavy drinking with his friends, he was referred to a psychiatrist. He underwent psychiatric treatment, which included psychological education and supportive therapy, and decided on abstinence. He has been followed-up regularly by surgeons and recipient coordinators, as well as by frequent psychiatric supervision. He has successfully continued to abstain from alcohol for 6 years.

The ALD is a major indication for LT, accounting for approximate 40% of all primary LTs in Europe[17] and about 25% in the United States[18]. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates after LT in ALD patients have been reported to be 84%, 78% and 73%, respectively, in Europe and 92%, 86% and 86%, respectively, in the United States[17,19]. Although LT for ALD compares favorably with other etiologies of liver cirrhosis[20], recidivism after LT for ALD negatively influences survival[3,4]. Early identification and monitoring of alcohol relapse are essential determinants of long-term outcomes after LT. Although psychosocial evaluation is mandatory for all transplant candidates, it is especially important in patients with ALD. To date, however, there has been a lack of firm consensus regarding psychosocial criteria for LT in patients with ALD. Based on our findings, we propose a set of comprehensive psychosocial criteria to preoperatively predict the risk of relapse after LT.

Although the minimum duration of sobriety before LT has not been determined conclusively, many transplant centers have adopted a minimum alcohol abstinence period of 6 mo as a criterion for transplantation. Abstinence for 6 mo may allow the clinical condition of ALD patients to stabilize or improve prior to LT[21] and has been associated with lower rates of post-transplant relapse[9,10]. However, few studies to date have assessed the accuracy of the 6-mo rule in predicting recidivism[22,23]. A recent survey in Japan showed that a pre-transplant sobriety cutoff of 18 mo was practical in identifying high-risk patients susceptible to harmful relapse and in selecting patients for deceased donor LT[22]. We regard our selection criteria, consisting of abstinence for 6 mo and promise to abstain throughout life, as essential prerequisites for LT.

In addition, it is important to evaluate psychosocial factors, with each institution establishing its own criteria. The psychosocial criteria for LT at our institution consist of five items: (1) absence of psychiatric comorbidity except for alcohol-related mental disease[15,24-27]; (2) adherence to medical treatment[26,28-30]; (3) understanding of and agreeing to transplant and support by the patient’s family[15,24,26,31,32]; (4) being employed or willing to work[15,16,27]; and (5) having an HRAR score ≤ 2 points, indicating a lower risk of return to drinking[15,16,27]. In our institution, we did not employ the measurement of blood concentrations of alcohol-related substances, such as ethanol and carbohydrate deficient transferrin.

Because patients with ALD may not fulfill all five criteria, it is necessary to evaluate whether they meet these criteria in a comprehensive way. These five items include risk factors for post-transplant relapse, including psychiatric comorbidities other than alcohol-related mental disease and higher HRAR score[27]. Although a previous study reported that HRAR score alone was not predictive of relapse[22], its inclusion as one of several criteria may be useful. Non-adherence to medical treatment has been reported to predict relapse[26,28,29]. The HRAR score higher than 3 will be associated with relapse into harmful drinking[15]. However, we suggest that evaluation based on HRAR score alone is not enough, and consider that ALD patients should be comprehensively evaluated.

The psychopathology of ALD frequently includes denial, both by patients and their families. Consequently, it may be difficult to evaluate risks of alcohol relapse following an initial interview with ALD patients. Patients should therefore be reevaluated for risk of alcohol relapse one month after their initial evaluation, with further reevaluations required if the risk of alcohol relapse remains difficult to evaluate. Unnecessary delays in making a decision should be avoided. However, repeated patient follow-up may reveal any alcohol-related pathology within the family, including the autonomous intention of the patient and whether the family is supportive.

Psychiatric follow-up after LT is also required[33]. In addition to pre-transplant evaluation, pre- and post-transplant counseling may minimize the relapse of alcoholism after LT. In our hospital, follow-up in the psychiatry outpatient department is mandatory for all patients, although symptoms such as insomnia or irritation may not be recognized. During follow-up, one of seven patients returned to heavy drinking after LT. However, this patient quit drinking after an immediate intervention by psychiatrists. The rate of alcohol relapse in this study, 14.3%, was lower than in previous studies[2,22,29].

The target in treating alcoholism is not merely abstention from alcohol. Rather, everyday life instruction is necessary to prevent resumption of drinking after LT. Patients should also be gradually introduced to a self-help group such as Alcoholics Anonymous. Many patients with ALD and their families deny having a problem with alcohol, as denial is a psychological mechanism to exclude painful thoughts. Only two of the seven patients who underwent LT in this study participated in a self-help group.

In conclusion, we propose a set of psychosocial evaluation criteria that may be useful in assessing risk of alcohol relapse in patients with ALD who are candidates for LT. These psychosocial evaluation criteria will result in improvements in the selection of ALD patients for transplantation and may increase the LT success rate. Additional well-designed studies evaluating our criteria are required to predict risk of alcohol relapse in ALD patients after LT and to determine the optimal timing of LT in patients with ALD.

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is one of the most common causes of advanced liver cirrhosis. The ALD is the second most common indication for liver transplantation (LT).

Post-transplant relapse of alcohol use can have a negative impact on patient outcomes. It is important to preoperatively assess the risk of post-transplant alcohol use.

To date, however, psychosocial evaluation criteria of LT for ALD have not been established. This psychosocial evaluation criteria may be useful in assessing the risk of relapse in patients who undergo LT for ALD.

Patients with ALD referred for LT require comprehensive evaluation, including evaluation of psychosocial criteria, to prevent alcoholic recidivism. This psychosocial evaluation criteria may be useful in assessing risk of alcohol relapse in patients with ALD who are candidates for LT.

This psychosocial evaluation criteria will result in improvements in the selection of ALD patients for transplantation and may increase the LT success rate.

To investigate factors, including psychosocial factors, associated with alcoholic use relapse after LT for ALD still remains a Achilles points to avoid relapse after LT procedure and comprehensive evaluation, including evaluation of psychosocial criteria, to prevent alcoholic recidivism can be necessary.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A, A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Boin IF, Higuera-de la Tijera MF, Keller F S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF

| 1. | Jaurigue MM, Cappell MS. Therapy for alcoholic liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:2143-2158. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 49] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lucey MR. Liver transplantation in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:751-759. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 72] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Faure S, Herrero A, Jung B, Duny Y, Daures JP, Mura T, Assenat E, Bismuth M, Bouyabrine H, Donnadieu-Rigole H. Excessive alcohol consumption after liver transplantation impacts on long-term survival, whatever the primary indication. J Hepatol. 2012;57:306-312. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 96] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Schmeding M, Heidenhain C, Neuhaus R, Neuhaus P, Neumann UP. Liver transplantation for alcohol-related cirrhosis: a single centre long-term clinical and histological follow-up. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:236-243. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rice JP, Lucey MR. Should length of sobriety be a major determinant in liver transplant selection? Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2013;18:259-264. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cuadrado A, Fábrega E, Casafont F, Pons-Romero F. Alcohol recidivism impairs long-term patient survival after orthotopic liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:420-426. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Lucey MR. Liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:300-307. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 73] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Berlakovich GA. Challenges in transplantation for alcoholic liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:8033-8039. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dew MA, DiMartini AF, Steel J, De Vito Dabbs A, Myaskovsky L, Unruh M, Greenhouse J. Meta-analysis of risk for relapse to substance use after transplantation of the liver or other solid organs. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:159-172. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 187] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kawaguchi Y, Sugawara Y, Yamashiki N, Kaneko J, Tamura S, Aoki T, Sakamoto Y, Hasegawa K, Nojiri K, Kokudo N. Role of 6-month abstinence rule in living donor liver transplantation for patients with alcoholic liver disease. Hepatol Res. 2013;43:1169-1174. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Addolorato G, Leggio L, Ferrulli A, Cardone S, Vonghia L, Mirijello A, Abenavoli L, D’Angelo C, Caputo F, Zambon A. Effectiveness and safety of baclofen for maintenance of alcohol abstinence in alcohol-dependent patients with liver cirrhosis: randomised, double-blind controlled study. Lancet. 2007;370:1915-1922. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Gramenzi A, Gitto S, Caputo F, Biselli M, Lorenzini S, Bernardi M, Andreone P. Liver transplantation for patients with alcoholic liver disease: an open question. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:843-849. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kimura H, Onishi Y, Sunada S, Kishi S, Suzuki N, Tsuboi C, Yamaguchi N, Imai H, Kamei H, Fujisiro H. Postoperative Psychiatric Complications in Living Liver Donors. Transplant Proc. 2015;47:1860-1865. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yates WR, Booth BM, Reed DA, Brown K, Masterson BJ. Descriptive and predictive validity of a high-risk alcoholism relapse model. J Stud Alcohol. 1993;54:645-651. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | De Gottardi A, Spahr L, Gelez P, Morard I, Mentha G, Guillaud O, Majno P, Morel P, Hadengue A, Paliard P. A simple score for predicting alcohol relapse after liver transplantation: results from 387 patients over 15 years. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1183-1188. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Haber PS, McCaughan GW. “I’ll never touch it again, doctor!”--harmful drinking after liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2007;46:1302-1304. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Burra P, Senzolo M, Adam R, Delvart V, Karam V, Germani G, Neuberger J. Liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease in Europe: a study from the ELTR (European Liver Transplant Registry). Am J Transplant. 2010;10:138-148. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 234] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Singal AK, Guturu P, Hmoud B, Kuo YF, Salameh H, Wiesner RH. Evolving frequency and outcomes of liver transplantation based on etiology of liver disease. Transplantation. 2013;95:755-760. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 221] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bhagat V, Mindikoglu AL, Nudo CG, Schiff ER, Tzakis A, Regev A. Outcomes of liver transplantation in patients with cirrhosis due to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis versus patients with cirrhosis due to alcoholic liver disease. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:1814-1820. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 127] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tan HH, Virmani S, Martin P. Controversies in the management of alcoholic liver disease. Mt Sinai J Med. 2009;76:484-498. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lucey MR, Brown KA, Everson GT, Fung JJ, Gish R, Keeffe EB, Kneteman NM, Lake JR, Martin P, McDiarmid SV. Minimal criteria for placement of adults on the liver transplant waiting list: a report of a national conference organized by the American Society of Transplant Physicians and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Liver Transpl Surg. 1997;3:628-637. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Egawa H, Ueda Y, Kawagishi N, Yagi T, Kimura H, Ichida T. Significance of pretransplant abstinence on harmful alcohol relapse after liver transplantation for alcoholic cirrhosis in Japan. Hepatol Res. 2014;44:E428-E436. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | McCallum S, Masterton G. Liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease: a systematic review of psychosocial selection criteria. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006;41:358-363. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Kelly M, Chick J, Gribble R, Gleeson M, Holton M, Winstanley J, McCaughan GW, Haber PS. Predictors of relapse to harmful alcohol after orthotopic liver transplantation. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006;41:278-283. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | DiMartini A, Dew MA, Day N, Fitzgerald MG, Jones BL, deVera ME, Fontes P. Trajectories of alcohol consumption following liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:2305-2312. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 144] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Telles-Correia D, Mega I. Candidates for liver transplantation with alcoholic liver disease: Psychosocial aspects. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:11027-11033. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Rustad JK, Stern TA, Prabhakar M, Musselman D. Risk factors for alcohol relapse following orthotopic liver transplantation: a systematic review. Psychosomatics. 2015;56:21-35. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 44] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Webb K, Shepherd L, Day E, Masterton G, Neuberger J. Transplantation for alcoholic liver disease: report of a consensus meeting. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:301-305. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Egawa H, Nishimura K, Teramukai S, Yamamoto M, Umeshita K, Furukawa H, Uemoto S. Risk factors for alcohol relapse after liver transplantation for alcoholic cirrhosis in Japan. Liver Transpl. 2014;20:298-310. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 68] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Telles-Correia D, Barbosa A, Mega I, Monteiro E. Psychosocial predictors of adherence after liver transplant in a single transplant center in Portugal. Prog Transplant. 2012;22:91-94. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 31. | Pfitzmann R, Schwenzer J, Rayes N, Seehofer D, Neuhaus R, Nüssler NC. Long-term survival and predictors of relapse after orthotopic liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:197-205. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 32. | Rodrigue JR, Hanto DW, Curry MP. Substance abuse treatment and its association with relapse to alcohol use after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2013;19:1387-1395. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |