Published online May 14, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i18.3349

Peer-review started: December 14, 2016

First decision: January 19, 2017

Revised: February 4, 2017

Accepted: April 12, 2017

Article in press: April 12, 2017

Published online: May 14, 2017

To describe the longitudinal course of acquisition of healthcare transition skills among adolescents and young adults with inflammatory bowel diseases.

We recruited adolescents and young adults (AYA) with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), from the pediatric IBD clinic at the University of North Carolina. Participants completed the TRxANSITION Scale™ at least once during the study period (2006-2015). We used the electronic medical record to extract participants’ clinical and demographic data. We used ordinary least square regressions with robust standard error clustered at patient level to explore the variations in the levels and growths of healthcare transition readiness.

Our sample (n = 144) ranged in age from 14-22 years. Age was significantly and positively associated with both the level and growth of TRxANSITION Scale™ scores (P < 0.01). Many healthcare transition (HCT) skills were acquired between ages 12 and 14 years, but others were not mastered until after age 18, including self-management skills.

This is one of the first studies to describe the longitudinal course of HCT skill acquisition among AYA with IBD, providing benchmarks for evaluating transition interventions.

Core tip: Adolescent and young adult patients with inflammatory bowel diseases need to transfer from pediatric to adult care, and inadequate preparation for this transfer can have negative consequences. In the past decade, the need to prepare pediatric patients for successful healthcare transitioning has received increased attention from researchers and clinicians. However, it was not clear at what age patients usually develop these transitioning skills. It is apparent from the current study that transition skills increase with age and that many transition skills are developed in early adolescence, while some important skills (i.e., self-management) are not mastered until early adulthood. This emphasizes the need to focus on skills that are mastered at a later age and investigate barriers and interventions to assure skills are mastered before transfer to adult care.

- Citation: Stollon N, Zhong Y, Ferris M, Bhansali S, Pitts B, Rak E, Kelly M, Kim S, van Tilburg MAL. Chronological age when healthcare transition skills are mastered in adolescents/young adults with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(18): 3349-3355

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i18/3349.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i18.3349

At least 20% of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) cases present during childhood or adolescence[1]. Patients with pediatric-onset IBD tend to have more complicated disease and may require more complex treatment plans than those who acquire IBD in adulthood[1]. Before adolescents reach young adulthood, it is necessary that they are prepared to transition their healthcare to adult-focused gastroenterologists and other providers. Ideally, this healthcare transition (HCT) is “uninterrupted, coordinated, developmentally appropriate, psychosocially sound, and comprehensive”[2], and culminates when young adults have achieved a level of mastery of certain disease knowledge and healthcare skills, including: understanding of their disease and treatment, and communicating independently with their healthcare providers[3-5].

There has been an increased emphasis on the development of HCT preparation and guidelines, both for adolescents and young adults (AYA) with chronic conditions[5], and for AYA with IBD in particular[3,4]. Despite an increase in transition-readiness initiatives, AYA with IBD often do not achieve full healthcare independence before transfer to adult providers[6-8]. There is evidence that a majority of adults with IBD regularly solicit assistance from a family member, friend, or spouse with picking up medications and developing a list of questions for their physician[6].

Despite the current literature that illustrates a lack of mastery of HCT skills before transfer to adult care, little is known about the natural, longitudinal trajectory of HCT skill acquisition. This paper reports the findings of an observational study of AYA with IBD in a large southeastern university teaching hospital. Through administration of a standardized HCT readiness measure during routine sub-specialty clinical visits, we aimed to describe the age at which AYA with IBD naturally master HCT skills.

This study was reviewed and granted approval by the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina.

Participants were recruited from the pediatric IBD clinic at the University of North Carolina between 2006 and 2015. Patients completed the questionnaire at regularly scheduled clinic visits. Patients were recruited on an ongoing basis, continuously adding to the sample size.

Demographic and clinical information were obtained from the patients’ electronic health records, available since 1984.

The TRxANSITION Scale™[9,10] was administered yearly by a trained professional to measure HCT knowledge and skills. The scale has 32 questions in total and examines the following 10 domains: Type of health condition, Rx knowledge of medication, Adherence, Nutrition, Self-management, Issues of reproduction, Trade/school, Insurance, Ongoing support and New healthcare providers[9,10]. Participants were asked to endorse one of the following responses for each item: 1 (knows a lot), 0.5 (knows a little), and 0 (doesn’t know). The scale has good reliability and validity with AYA with chronic conditions, including IBD (r = 0.71)[9,10]. The maximum total score is 10 and the maximum score for each subdomain is 1. For this study, we defined mastery of an HCT skill as a subdomain average score of > 0.75.

AYAs completed the TRxANSITION Scale™ at least once, but possibly up to three times during the 2006 to 2015 period. To examine the trajectory of TRxANSITION Scale™ total and subtotal scores, different samples were used: Sample 1 consisted of information on all patients (n) and their first observed score(s) (n = 144; s = 144). Sample 2 included information from all patients and all of their observed scores (n = 144; s = 226). Sample 3 consisted of all patients with at least two scores (n = 59; s = 141). Sample 1 was used to describe baseline sample characteristics. To illustrate the transition skills at different age stages, we calculated the average total and subtotal TRxANSITION Scale™ score by different age groups using Sample 2. Raw wave-to-wave and adjusted yearly score changes were calculated using Sample 3.

We employed two ordinary least square (OLS) regressions to further explore the variations in the levels and growths of HCT readiness. The first regression used total TRxANSITION Scale™ score as the dependent variable, and the independent variables included individual’s age, gender, race, health insurance, and age at diagnosis. Using Sample 2, the estimated coefficients reflect the marginal effects of the explanatory variables on the levels of transition scores. The second regression included the lagged transition score as an additional independent variable. Conditional on the lagged transition score, the coefficients in the regression reflect the marginal effects of the explanatory variables on the growth in transition score between two scores. Sample 3 was used to estimate the second regression. We estimated robust standard errors clustered at the patient level for both regressions. All statistical analyses were performed in STATA 13.0.

Our sample included a total of 256 TRxANSITION Scale™ scores from 144 patients with IBD ranging in ages from 12-22 years (mean age 15.9 ± 2.0 years). See Table 1 for additional information on the sample demographics. Eighty-five patients completed the questionnaire once, 41 completed it twice, and 18 patients completed the questionnaire three times or more.

| Variable | n | mean ± SD/percentages1 |

| Age at baseline | 144 | 15.67 ± 1.9 |

| Age (time-varying) | 226 | 15.88 ± 2.0 |

| Age of diagnosis | 144 | 12.20 ± 2.8 |

| Female | 77 | 53.5% |

| Race: White | 102 | 70.8% |

| Race: AFAM | 31 | 21.5% |

| Race: Hispanic | 3 | 2.1% |

| Race: Other | 8 | 5.6% |

| Private Health Insurance | 114 | 79.2% |

| Public Health Insurance | 26 | 18.1% |

| Self-pay | 4 | 2.8% |

Table 2 shows the TRxANSITION Scale™ score means by age. With scores of ≥ 75% on each subdomain, many HCT skills (as measured by the subscales) were mastered between the ages of 12 and 14 years (see Table 2). These were primarily skills related to knowledge, such as knowledge of Type of chronic condition, Rx= medications, and Nutrition, but also included Adherence and Ongoing support. The other half of the HCT transition skills were not mastered until after the age of 18.

| Age | ||||

| 12-14 | 15-16 | 17-18 | > 18 | |

| Type of chronic health condition | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.92 | 0.98 |

| Medications (Rx) | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.86 | 0.89 |

| Adherence | 0.83 | 0.86 | 0.79 | 0.86 |

| Nutrition | 0.80 | 0.76 | 0.84 | 0.80 |

| Ongoing support | 0.87 | 0.91 | 0.97 | 0.93 |

| Issues of reproduction | 0.29 | 0.48 | 0.66 | 0.81 |

| Trade/school | 0.44 | 0.49 | 0.70 | 0.83 |

| Insurance | 0.48 | 0.47 | 0.66 | 0.76 |

| New health care providers | 0.48 | 0.41 | 0.59 | 0.74 |

| Self-management skills | 0.28 | 0.38 | 0.49 | 0.77 |

| Number of observations | 65 | 73 | 67 | 21 |

The mean gain between measurements in TRxANSITION Scale™ Score was 1.3 ± 1.3, without adjusting the time period in-between. The mean yearly gain between two score measurements was 1.6 ± 2.2. Overall, we observed the lowest gains over time in Adherence and the highest gains over time in Trade/school knowledge (See Table 3).

| Sections | Raw wave-to-wave changes | Yearly (time adjusted) changes | ||

| mean ± SD | min-max | mean ± SD | min-max | |

| Type of chronic health condition | 0.08 ± 0.20 | -0.33-0.67 | 0.10 ± 0.33 | -0.64-1.58 |

| Medications (Rx) | 0.06 ± 0.21 | -0.50-0.50 | 0.08 ± 0.34 | -1.19-1.19 |

| Adherence | 0.01 ± 0.23 | -0.50-0.50 | 0.04 ± 0.31 | -0.73-1.11 |

| Nutrition | 0.03 ± 0.27 | -0.67-0.83 | 0.07 ± 0.40 | -0.80-1.84 |

| Ongoing support | 0.01 ± 0.33 | -1.00-1.00 | 0.02 ± 0.53 | -2.21-1.86 |

| Issues of reproduction | 0.24 ± 0.41 | -0.50-1.00 | 0.26 ± 0.59 | -1.19-1.89 |

| Trade/school | 0.45 ± 0.55 | -1.00-1.00 | 0.51 ± 0.91 | -1.86-2.48 |

| Insurance | 0.17 ± 0.30 | -0.38-0.75 | 0.25 ± 0.47 | -0.47-1.92 |

| New health care providers | 0.17 ± 0.33 | -0.50-1.00 | 0.23 ± 0.52 | -1.19-2.01 |

| Self-management skills | 0.12 ± 0.27 | -0.67-1.00 | 0.06 ± 0.34 | -1.59-1.23 |

| Total | 1.34 ± 1.31 | -1.61-5.17 | 1.62 ± 2.18 | -3.08-10.91 |

| Number of observations | 82 | 811 | ||

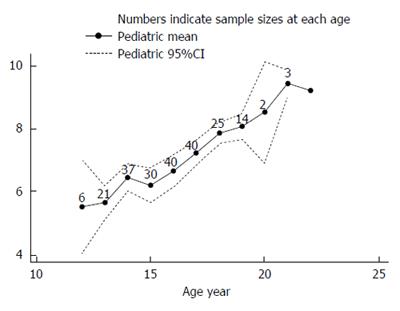

We found that age was significantly and positively associated with both the level and gains in transition scores (P < 0.01; Table 4 and Figure 1) after adjusting for key variables. On average, females had higher transition scores, when compared to their male counterparts. However, both males and females showed similar trends in gains in their scores over time. African Americans had lower transition scores compared to Caucasians, but these groups did not differ in gains of their HCT scores over time. Patients of other races performed worse in both level and gains in transition score over time when compared to their Caucasian counterparts. Compared to patients with private insurance, patients with public insurance had notably lower score gains over time; and patients with no health insurance had significantly lower score levels and gains. Transition score in the last period was significantly and positively associated with the score in the current period, implying consistency between an individual’s score measures.

| Variable | Level effect | Growth effect | ||

| Coefficient | P value | Coefficient | P value | |

| Age | 0.423 | 0.00 | 0.213 | 0.00 |

| Female | 0.412 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.90 |

| Race: African American | -0.432 | 0.06 | -0.06 | 0.87 |

| Race: Other | -0.753 | 0.01 | -0.431 | 0.09 |

| Public insurance | -0.02 | 0.94 | -0.963 | 0.01 |

| No insurance | -0.701 | 0.07 | -0.701 | 0.06 |

| Age at diagnosis | -0.00 | 0.99 | 0.05 | 0.23 |

| Lag total score | 0.423 | 0.00 | ||

| Constant | 0.05 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.26 |

| n | 226 | 82 | ||

| R square | 0.32 | 0.52 | ||

This study’s strengths include longitudinal observations on a validated, standardized HCT readiness scale that does not rely on self-report, since clinical information was available through electronic health records. It is the first study to determine skill acquisition by age, pointing to age-appropriate HCT preparation. Our study had some limitations. Although appropriate for statistical analysis, our single center sample of 144 was relatively small, and our within age group sample sizes were even smaller. Due to the nature of clinical care, we were not able to have all participants complete the questionnaire more than once. Future studies should build in repeating measures for the majority of participants, to gather additional data on the nature of skill acquisition and the rate at which they are acquired throughout adolescence.

This study examined the longitudinal course of HCT skills among a sample of AYA with IBD. We found that skill acquisition is positively associated with age. As well, we observed that while half of the HCT skills were mastered in early adolescence (ages 12-14), the other half were not mastered until age 18 or older. Some of these skills are age appropriately mastered later, such as knowing about trade/school, insurance or how to find a new healthcare provider. More notable is the fact that self-management skills were not mastered by the age of 18.

Our study is one of the first to show the age at which AYA with IBD typically master HCT skills. These findings can be used in clinical care, in clinical settings with AYA of a similar demographic, in order to benchmark AYA’s skills in relation to their peers, ensure that they are on track in their development, and as a reference point for the development of clinical interventions teaching skill mastery earlier and in a more step-wise fashion. Our results are consistent with previous literature showing a significant and positive relationship between age and skill acquisition[8,11-13]. They add to these findings, by showing that age also predicts mastery of skills over time. Previous studies also found that few AYA achieve mastery of HCT skills by age 18, especially in the domains of disease self-management and understanding of health insurance[8,11,12]. As well, many adults with IBD continue to rely on family members to assist them with their day-to-day care, well past young adulthood[6]. While other similar studies surveyed AYA starting at age 16, our study adds to the literature by including younger adolescents (ages 12-15) and multiple longitudinal observations. By including this younger cohort, we learned that half of HCT skills are acquired by early adolescence, while the other half are not acquired until young adulthood.

We found increased HCT transition skills among female AYA, which is consistent with the previous literature[14]. We also found significantly lower gains in HCT skills among AYA with public insurance and without insurance, when compared to their peers with private insurance. AYA without insurance and with public insurance are most likely from low-income families. This finding is consistent with previous literature showing that higher household income predicted increased transition readiness[14], and a family income of ≥ 400% of the federal poverty level and possession of private insurance were positively associated with AYA achieving desired transition outcomes[15]. Additionally, we found disparities in HCT skill acquisition between Caucasian AYA and AYA of other races. This is consistent with previous literature highlighting racial disparities in the transition to adulthood for youth with special healthcare needs[13,16-18]. Both low-income and non-white AYA are already at risk for poorer health outcomes than their Caucasian peers from, middle and high-income families[19]. Therefore, it is critical that additional attention is paid to ensuring that these AYA achieve mastery of HCT skills, to assist them in remaining as healthy as possible. Given the disparity in skill acquisition, future studies might consider whether current methods of HCT intervention need to be adapted to meet the unique needs of low-income and non-white AYA.

From a clinical care perspective, it is crucial to account for the finding that independent disease self-management and understanding of health insurance are not mastered until after age 18. There is evidence that in the United States, approximately 60% of young adults ages 18 to 24 live outside the parental home[20]. Therefore, our finding that AYA with IBD are unlikely to be fully independent in their healthcare by the time of assumed independence presents significant challenges to meeting their healthcare needs. Based on our findings and similar findings in studies cited above, it is important to consider whether mastery of more sophisticated concepts, such as an understanding of health insurance, are too complex for adolescents. In some studies, providers have identified psychological and developmental maturity as more important factors in assessing transition readiness than chronological age[21,22]. Additionally, studies on neurological development show that the brain does not mature until young adulthood[23,24]. The prefrontal cortex, responsible for executive functioning and goal orientation, is one of the last to mature[24-27]. Navigating some of the complex systems of the US healthcare system, such as health insurance and reimbursement, requires a relatively high level of executive functioning, so it is possible that adolescents are simply not yet cognitively equipped to master these skills before they reach young adulthood. Conversely, it is possible that AYA do not develop these skills at a younger age because their parents and healthcare team do not have an expectation that adolescents participate in these responsibilities. Some studies suggest that parental management of health issues may even act as a barrier to HCT skill mastery[22,28]. This may be especially true in older adolescents, as parents can be hesitant to relinquish control of the AYA’s healthcare[22,29] or uncertain about how to do so effectively[30,31]. Future studies may further examine adolescents’ capacity to learn more complex HCT skills. As well, future studies may also investigate the parental role further, and develop interventions to assist parents with transferring the responsibility for healthcare skills to their child during adolescence. Future interventions should focus on assisting AYA in developing mastery of HCT transition skills before living independently. This may be done effectively by leveraging parents to help build these skills in their teenage children.

In summary, our study is one of the first to provide a description of the natural longitudinal course of HCT skill acquisition among AYA with IBD. These findings can be helpful in benchmarking clinical care and program development. Additionally, our results point to a need to better understand the reason for skill acquisition at different ages and the reasons behind such late mastery of self-management skills and knowledge of insurance. Further research should examine possible barriers, including parental involvement and/or lack of explicit teaching or intervention in these areas.

At least 20% of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) cases present during childhood or adolescence. Patients with pediatric-onset IBD tend to have more complicated disease and may require more complex treatment plans than those who acquire IBD in adulthood. Despite the current literature that illustrates a lack of mastery of healthcare transition (HCT) skills before transfer to adult care, little is known about the natural, longitudinal trajectory of HCT skill acquisition.

This paper reports the findings of an observational study of AYA with IBD in a large southeastern university teaching hospital. Through administration of a standardized HCT readiness measure during routine sub-specialty clinical visits, the authors aimed to describe the age at which AYA with IBD naturally master HCT skills.

This is one of the first studies to describe the longitudinal course of HCT skill acquisition among AYA with IBD, providing benchmarks for evaluating transition interventions.

The results particularly highlight the need for transition services to continue until at least age 19-20.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Gardlik R, Sandberg KC, Sebastian S S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Kelsen J, Baldassano RN. Inflammatory bowel disease: The difference between children and adults. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:S9-S11. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 65] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ethier KA, Harper CR, Hoo E, Dittus PJ. The Longitudinal Impact of Perceptions of Parental Monitoring on Adolescent Initiation of Sexual Activity. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59:570-576. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 968] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 916] [Article Influence: 29.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Baldassano R, Ferry G, Griffiths A, Mack D, Markowitz J, Winter H. Transition of the patient with inflammatory bowel disease from pediatric to adult care: recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;34:245-248. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Leung Y, Heyman MB, Mahadevan U. Transitioning the adolescent inflammatory bowel disease patient: guidelines for the adult and pediatric gastroenterologist. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:2169-2173. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 73] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, Medicine AC of P-AS of IM. A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2002;110:1304-1306. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Fishman LN, Mitchell PD, Lakin PR, Masciarelli L, Flier SN. Are Expectations Too High for Transitioning Adolescents With Inflammatory Bowel Disease? Examining Adult Medication Knowledge and Self-Management Skills. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;63:494-499. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Trivedi I, Keefer L. The Emerging Adult with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Challenges and Recommendations for the Adult Gastroenterologist. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:260807. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gray WN, Holbrook E, Morgan PJ, Saeed SA, Denson LA, Hommel KA. Transition readiness skills acquisition in adolescents and young adults with inflammatory bowel disease: findings from integrating assessment into clinical practice. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:1125-1131. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 64] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cantú-Quintanilla G, Ferris M, Otero A. Validation of the UNC TRxANSITION ScaleTMVersion 3 Among Mexican Adolescents With Chronic Kidney Disease. J Pediatr Nurs. 2015;30:e71-e81. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ferris ME, Harward DH, Bickford K, Layton JB, Ferris MT, Hogan SL, Gipson DS, McCoy LP, Hooper SR. A clinical tool to measure the components of health-care transition from pediatric care to adult care: the UNC TR(x)ANSITION scale. Ren Fail. 2012;34:744-753. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 122] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fishman LN, Barendse RM, Hait E, Burdick C, Arnold J. Self-management of older adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: a pilot study of behavior and knowledge as prelude to transition. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2010;49:1129-1133. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 72] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Whitfield EP, Fredericks EM, Eder SJ, Shpeen BH, Adler J. Transition readiness in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease: patient survey of self-management skills. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;60:36-41. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 46] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Huang JS, Tobin A, Tompane T. Clinicians poorly assess health literacy-related readiness for transition to adult care in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. 2012;10:626-632. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 50] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Javalkar K, Johnson M, Kshirsagar AV, Ocegueda S, Detwiler RK, Ferris M. Ecological Factors Predict Transition Readiness/Self-Management in Youth With Chronic Conditions. J Adolesc Health. 2016;58:40-46. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 48] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | McManus MA, Pollack LR, Cooley WC, McAllister JW, Lotstein D, Strickland B, Mann MY. Current status of transition preparation among youth with special needs in the United States. Pediatrics. 2013;131:1090-1097. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 165] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lotstein DS, Kuo AA, Strickland B, Tait F. The Transition to Adult Health Care for Youth With Special Health Care Needs: Do Racial and Ethnic Disparities Exist? PEDIATRICS. 2010;126:S129-S136. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 59] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Richmond N, Tran T, Berry S. Receipt of transition services within a medical home: do racial and geographic disparities exist? Matern Child Health J. 2011;15:742-752. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Richmond NE, Tran T, Berry S. Can the Medical Home eliminate racial and ethnic disparities for transition services among Youth with Special Health Care Needs? Matern Child Health J. 2012;16:824-833. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Williams DR, Pamuk E. Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: what the patterns tell us. Am J Public Health. 2010;100 Suppl 1:S186-S196. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 962] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 847] [Article Influence: 60.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Manzoni A. Intergenerational Financial Transfers and Young Adults’ Transitions In and Out of the Parental Home. Soc Curr. 2016;3:349-366. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Wright EK, Williams J, Andrews JM, Day AS, Gearry RB, Bampton P, Moore D, Lemberg D, Ravikumaran R, Wilson J. Perspectives of paediatric and adult gastroenterologists on transfer and transition care of adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. Intern Med J. 2014;44:490-496. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Paine CW, Stollon NB, Lucas MS, Brumley LD, Poole ES, Peyton T, Grant AW, Jan S, Trachtenberg S, Zander M. Barriers and facilitators to successful transition from pediatric to adult inflammatory bowel disease care from the perspectives of providers. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:2083-2091. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 72] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gogtay N, Giedd JN, Lusk L, Hayashi KM, Greenstein D, Vaituzis AC, Nugent TF, Herman DH, Clasen LS, Toga AW. Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8174-8179. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3626] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3523] [Article Influence: 176.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yurgelun-Todd D. Emotional and cognitive changes during adolescence. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:251-257. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 462] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 380] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Luna B, Padmanabhan A, O’Hearn K. What has fMRI told us about the development of cognitive control through adolescence? Brain Cogn. 2010;72:101-113. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 554] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 510] [Article Influence: 36.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Dumontheil I, Houlton R, Christoff K, Blakemore SJ. Development of relational reasoning during adolescence. Dev Sci. 2010;13:F15-F24. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sturman DA, Moghaddam B. The neurobiology of adolescence: changes in brain architecture, functional dynamics, and behavioral tendencies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:1704-1712. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 176] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Iles N, Lowton K. What is the perceived nature of parental care and support for young people with cystic fibrosis as they enter adult health services? Health Soc Care Community. 2010;18:21-29. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Heath G, Farre A, Shaw K. Parenting a child with chronic illness as they transition into adulthood: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of parents’ experiences. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100:76-92. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 111] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Akre C, Suris JC. From controlling to letting go: what are the psychosocial needs of parents of adolescents with a chronic illness? Health Educ Res. 2014;29:764-772. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | van Staa AL, Jedeloo S, van Meeteren J, Latour JM. Crossing the transition chasm: experiences and recommendations for improving transitional care of young adults, parents and providers. Child Care Health Dev. 2011;37:821-832. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 177] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |