Published online Sep 14, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i34.7708

Peer-review started: March 27, 2016

First decision: May 12, 2016

Revised: June 7, 2016

Accepted: June 15, 2016

Article in press: June 15, 2016

Published online: September 14, 2016

Processing time: 165 Days and 13.5 Hours

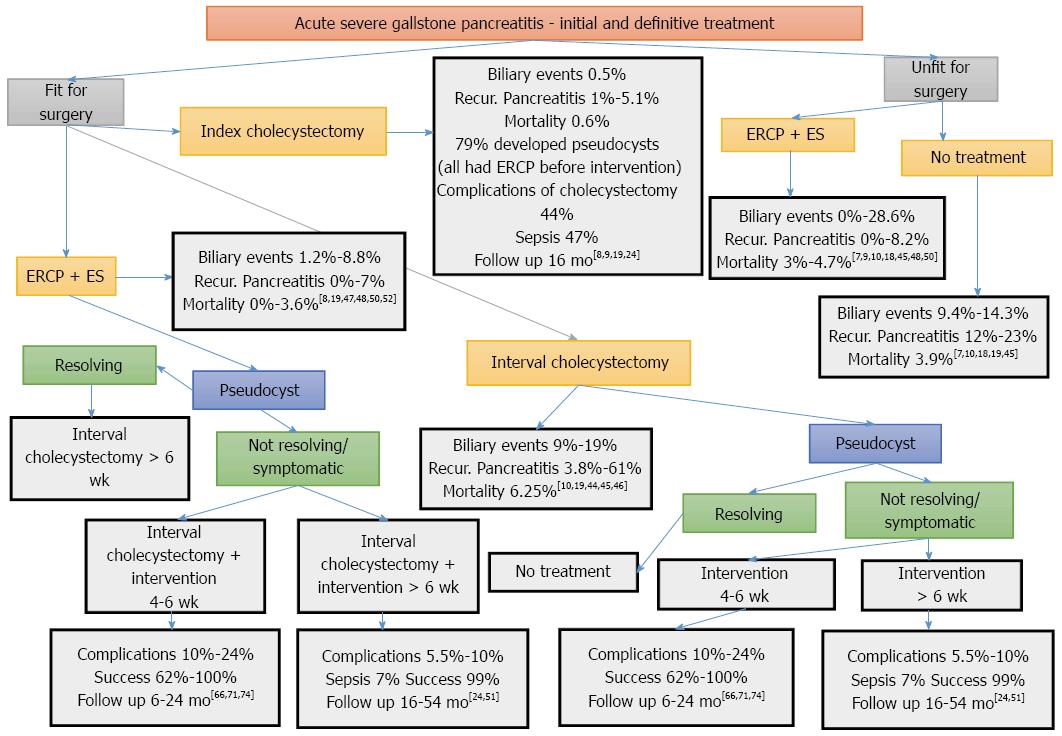

Cholelithiasis is the most common cause of acute pancreatitis, accounting 35%-60% of cases. Around 15%-20% of patients suffer a severe attack with high morbidity and mortality rates. As far as treatment is concerned, the optimum method of late management of patients with severe acute biliary pancreatitis is still contentious and the main question is over the correct timing of every intervention. Patients after recovering from an acute episode of severe biliary pancreatitis can be offered alternative options in their management, including cholecystectomy, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and sphincterotomy, or no definitive treatment. Delaying cholecystectomy until after resolution of the inflammatory process, usually not earlier than 6 wk after onset of acute pancreatitis, seems to be a safe policy. ERCP and sphincterotomy on index admission prevent recurrent episodes of pancreatitis until cholecystectomy is performed, but if used for definitive treatment, they can be a valuable tool for patients unfit for surgery. Some patients who survive severe biliary pancreatitis may develop pseudocysts or walled-off necrosis. Management of pseudocysts with minimally invasive techniques, if not therapeutic, can be used as a bridge to definitive operative treatment, which includes delayed cholecystectomy and concurrent pseudocyst drainage in some patients. A management algorithm has been developed for patients surviving severe biliary pancreatitis according to the currently published data in the literature.

Core tip: There is a paucity of data as to which of the following treatment options, including cholecystectomy, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and sphincterotomy, drainage techniques for fluid collections and pseudocysts, or no definitive treatment, is the optimal for patients after recovering from an acute episode of severe biliary pancreatitis. The complexity of pancreatitis regarding its course, patient’s performance status, and the variety of available interventions should be taken into consideration, raising the need for multidisciplinary management and individualization of every case.

- Citation: Dedemadi G, Nikolopoulos M, Kalaitzopoulos I, Sgourakis G. Management of patients after recovering from acute severe biliary pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(34): 7708-7717

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i34/7708.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i34.7708

The most common cause of acute pancreatitis in many western and Asian countries is cholelithiasis, accounting for 35%-60% of cases[1]. Most patients experience a relatively benign course of pancreatitis, but 15%-20% of patients suffer a severe attack[2], which is associated with high morbidity and an estimated mortality rate of 20%-30%[1]. Severe acute pancreatitis is defined by the presence of organ failure persisting beyond 48 h[2,3]. As far as the treatment is concerned, the optimum method for late management of patients with severe acute biliary pancreatitis is still contentious and the main question is the correct timing of every intervention. Long-term management of symptomatic cholelithiasis aims at minimizing the risk of new biliary events. In the study of Melman et al[4], > 50% of patients with biliary pancreatitis required laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy as part of the overall management. The American College of Gastroenterology and the International Association of Pancreatology/American Pancreatic Association (IAP/APA) Working Group recommend that definitive treatment in acute biliary pancreatitis should include cholecystectomy as the treatment of choice, thus avoiding recurrent biliary events[5,6]. However, 25%-50% of patients do not undergo cholecystectomy for a variety of reasons, regardless of current guidelines[7-9]. In a recent retrospective study including 5079 patients initially treated with sphincterotomy, interval cholecystectomy was the most efficient method for preventing episodes of recurrent biliary pancreatitis and offered the best long-term outcomes[10]. The timing of cholecystectomy in patients with peripancreatic fluid collections has not yet been determined. Early cholecystectomy raises the risk of a second general anesthetic or a risk of a second interventional procedure to manage persistent fluid collections. Our searches of the literature have revealed the fact that peripancreatic fluid collection and pseudocysts must be considered in the timing of cholecystectomy after an episode of moderate to severe biliary pancreatitis has not been addressed extensively. Certainly, there are ample reports in the literature regarding the timing of intervention for pseudocyst[11,12].

Currently available therapeutic options for patients who have survived severe biliary pancreatitis are: (1) conservative management; (2) index cholecystectomy; (3) endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and sphincterotomy; (4) interval cholecystectomy; (5) intervention for pseudocyst and walled-off necrosis; and (6) a combination of all or some of the above options. We assume that selective use of ERCP and sphincterotomy combined with interval cholecystectomy and concurrent pseudocyst management, if required, is the best option for treating patients after recovering from an acute episode of severe biliary pancreatitis.

A literature search was performed concerning the management of patients after recovering from an acute episode of severe biliary pancreatitis. The electronic databases MEDLINE, PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library and Google Scholar were used to search for relevant articles published in 1976-2016, using the following terms and/or combinations in their titles, abstracts, or keyword lists: acute pancreatitis, biliary pancreatitis, severe acute pancreatitis, pancreatic pseudocysts, index cholecystectomy, interval cholecystectomy, percutaneous pseudocyst drainage, endoscopic pseudocyst drainage, surgical pseudocyst management. The above-mentioned terms were used in [MeSH] (PubMed and Cochrane Library), where applicable; otherwise, they were combined using “AND/OR” and asterisks.

The following exclusion criteria were initially applied to all articles identified: publication of abstract only, case reports, and mean or median follow-up of 6 mo. Inclusion criteria were: observational cohort studies, randomized trials, reviews, meta-analyses, systematic reviews and Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews, studies available in full text, and published in the English language. Further references from the selected articles were reviewed manually to supplement the electronic search for additional relevant articles. The following variables concerning studies that address the management of patients with acute severe biliary pancreatitis were recorded: authors, journal and year of publication, country of origin, trial duration and participant demographics. Data concerning follow-up evaluation, ratios and percentages of morbidity, mortality, biliary events, recurrent pancreatitis, sepsis and other complications according to each treatment option were recorded in a database (Microsoft Excel spreadsheet).

Patients after recovering from an acute episode of severe biliary pancreatitis can be offered alternative options in their management, including cholecystectomy, ERCP and sphincterotomy, or no definitive treatment. Identifying these patients is a major concern because it affects the type and timing of intervention[13]. The implementation of appropriate treatment is directly correlated with the patients’ performance status, as frail elderly patients or patients with an impaired general condition and severe comorbid disease are usually unfit for surgery[5,6]. One also has to take into account that a number of patients who have survived severe biliary pancreatitis may develop pseudocysts or walled-off necrosis. Patients are generally considered fit for surgery according to their physiological fitness and functional capacity to cope with the above-mentioned procedures/interventions. There is a wide variety of prediction models referred to in the literature and used in different centers[14,15]. Adequate treatment must be provided according to patients’ general condition, offering alternative options, such as percutaneous, endoscopic or surgical treatment[4,16,17].

Conservatively treated patients after recovering from an acute episode of biliary pancreatitis have a significant risk of developing recurrent biliary events[7,10,18]. A large observational study by El-Dhuwaib et al[9], including 5454 patients, found that patients who did not undergo definitive treatment at index admission had an increased risk of recurrent biliary pancreatitis with a cumulative readmission rate of 4% within 2 wk after discharge, 7.7% within 6 wk and 12.8% within 52 wk.

Cholecystectomy: Cholecystectomy is the definitive treatment for acute biliary pancreatitis[5,6]. A significantly decreased risk of recurrent biliary pancreatitis, ranging between 1% and 5.1% is observed in patients who undergo index cholecystectomy, as it does not entirely prevent recurrent disease[8,9,19]. A population-based study questions the effectiveness of cholecystectomy for preventing recurrent episodes of acute pancreatitis in patients with neither a significant elevation of liver tests on day 1 of acute pancreatitis nor stones or sludge in the gallbladder on initial ultrasound evaluation, as recurrence rates were 34% and 61%, respectively. Recurrent attacks of acute pancreatitis after cholecystectomy were low when acute pancreatitis was associated with significantly elevated liver enzymes on day 1 of index admission[20].

Open cholecystectomy has a limited role; it can be performed along with debridement of necrotizing pancreatitis, and, in cases where a pancreatic pseudocyst is present, after unsuccessful percutaneous or endoscopic approaches, and in failed laparoscopy[13,21,22]. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the preferred approach, offering all the well-known advantages of minimally invasive procedures. The timing of laparoscopic cholecystectomy after an episode of mild acute biliary pancreatitis is controversial, whereas in severe pancreatitis, current guidelines recommend delaying cholecystectomy until after resolution of inflammatory process, usually not earlier than 6 wk after onset of acute pancreatitis[5,6,23].

According to the IAP/APA Working Group, in patients with peripancreatic collections, cholecystectomy should be delayed until collections either resolve, or, if they persist > 6 wk, cholecystectomy can be performed safely at this time[6]. Nealon et al[24] suggest that nonoperative management of the pseudocyst, as a bridge to definitive operative treatment, which includes delayed cholecystectomy and concurrent pseudocyst drainage, can be appropriate for a certain number of patients.

Need for ERCP and sphincterotomy: The AGA Institute Technical Review on Acute Pancreatitis maintains that ERCP should be performed in patients with a high suspicion of a persistent common bile duct stone[25], and the IAP/APA Working Group claims that ERCP is perhaps advisable in biliary pancreatitis with common bile duct obstruction, and possibly not indicated in predicted severe biliary pancreatitis without cholangitis[6]. Furthermore, the American College of Gastroenterology guidelines state that ERCP is not required in most patients with biliary pancreatitis who do not present with laboratory or clinical evidence of persistent biliary obstruction[5]. The majority of patients with biliary pancreatitis have spontaneous passage of stones into the duodenum[26], possibly rendering ERCP redundant, thus reducing potential associated complications. ERCP-related complications range from 5% to 10% and mortality from 0.2% to 0.5%, therefore, accurate prediction of common bile duct stones is required to avoid unnecessary interventions[27,28]. The decision to perform ERCP is often taken without substantial supporting evidence and is commonly based on biochemical (presence of cholestatic liver biochemistry) and radiological (dilated common bile duct) criteria, although they are proven to be unreliable factors for detecting the presence of common bile duct stones[29]. Subsequent to an episode of biliary pancreatitis, ERCP and sphincterotomy can be performed on an elective basis for extraction of impacted biliary stone[30], but there is no evidence regarding the optimal timing of ERCP in patients with biliary pancreatitis without cholangitis[6].

Recent noninvasive imaging modalities, such as endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) are at present accurate in detecting intraductal stones and identifying patients with persistent obstruction[31,32]. Sensitivity and specificity for detecting common bile duct stones for MRCP were 92% and 97%, respectively, and for EUS, 89% and 94%, respectively[31,32]. The sensitivity of MRCP decreases to about 65% when diagnosing stones < 5 mm, while the sensitivity of EUS does not vary with stone size[32]. This is particularly important because small stones are a common cause of biliary pancreatitis. EUS is more accurate than MRCP in the detection of intraductal stones < 5 mm, but MRCP is a less invasive method, less dependent on the operator and generally available, so there is no clear predominance of MRCP or EUS[6]. These imaging modalities are of most importance in deciding which patients can benefit from ERCP and sphincterotomy[29]. However, no specific evidence exists in the setting of severe acute biliary pancreatitis[33]. MRCP or EUS instead of ERCP should be carried out for suspected common bile duct stones in patients with biliary pancreatitis in the absence of cholangitis or biliary obstruction[5,29]. EUS is preferred over MRCP because EUS and ERCP can be performed in a single session if required. Savides noted that, even if MRCP reveals an intraductal stone, it is still worth considering EUS immediately before ERCP[34] because about 21% of intraductal stones (especially those < 8 mm) can pass spontaneously, which can occur in the interval between MRCP and ERCP[26]. In a recent review, Anderloni et al[35] state that EUS has recently been proposed as the new gold standard in the diagnosis of choledocholithiasis, as it is well known that small stones occasionally cannot be detected during ERCP; stones < 4 mm mainly in dilated common bile ducts can be hidden by contrast injection. The use of EUS before ERCP for stones < 4 mm is supported by sufficient evidence, as about two-thirds of ERCPs can be avoided[36].

Patients with pseudocysts and walled-off necrosis: Patients with persistent organ failure (> 48 h) in the late phase of severe acute pancreatitis are more likely to develop local complications, while some patients may recover without complications[3]. According to the revised Atlanta classification, local complications include: acute peripancreatic fluid collection, pancreatic pseudocyst, acute necrotic collection, and walled-off necrosis[2]. Localized collections persisting for > 4 wk can evolve into either a pseudocyst, if containing fluid only, or walled-off necrosis, if containing solid necrotic material; both within a well-defined wall[2]. A pseudocyst occurs after the onset of interstitial edematous pancreatitis but also in the setting of acute necrotizing pancreatitis as a result of disconnected duct syndrome, while walled-off necrosis occurs after the onset of necrotizing pancreatitis[37]. The distinction between these two entities was initiated in the 2012 revised Atlanta classification; therefore, the previously published papers do not contain this differentiation.

Acute peripancreatic fluid collections and pseudocysts are the most frequent complications following acute severe pancreatitis. Pancreatic pseudocysts have been traditionally treated surgically and this approach is still frequently used. The recent trend in the management of symptomatic pseudocysts has evolved towards minimally invasive therapy, such as endoscopic and image-guided percutaneous catheter drainage, leaving laparoscopic and open surgical techniques in case of failure of the above-mentioned techniques[33]. Proper patient selection is essential to decide on the best available technique for each and every patient. Treatment is a complex decision-making procedure, individualized for each patient, encompassing a multidisciplinary approach according to local expertise with endoscopic, percutaneous, or surgical techniques. A recent review has reported short-term clinical success rates of 85 % for endoscopic drainage, 83 % for surgical techniques and 67 % for percutaneous drainage, and complication rates were 16 %, 45 % and 34 % for endoscopic, surgical and percutaneous approaches, respectively[38].

Ductal anatomical abnormalities are more frequently encountered after severe acute pancreatitis. Although there is a lack of epidemiological data, the incidence of disconnected pancreatic duct syndrome is 10%-30% among patients with severe acute pancreatitis[39]. According to the revised Atlanta definition of pseudocysts, communication of a pseudocyst with the main duct occurs rarely[2], while previous studies report that 25%-58% of pseudocysts may communicate with the pancreatic duct[40]. Displaying such a communication or a disconnected pancreatic duct syndrome is essential in order to establish proper management. ERCP might be considered to further delineate anatomy, but it is not necessary when high-quality cross-sectional imaging (MRCP) is available[41]. The concurrent use of secretin has improved the diagnostic yield of MRCP and it is suggested to be valuable in assessing ductal continuity[42]. The ready availability of MRCP renders it the preferred imaging study. ERCP is an invasive method with the risk of contaminating the pseudocyst[33]. Once ERCP is carried out preoperatively, it should be done in close proximity to interventions to reduce the risk of contaminating the pseudocyst[43].

Schematic presentation of the alternative treatment options and their outcomes is depicted in Figure 1.

Conservative treatment: Conservatively treated patients after recovering from an acute episode of biliary pancreatitis have a significant risk of developing recurrent biliary events[7]. Studies have reported recurrence rates of biliary pancreatitis between 18% and 61% while patients are waiting to undergo cholecystectomy when conservatively treated at index admission[19,44]. Around 4%-50% of cases of recurrent biliary pancreatitis can be severe[19]. In a recent retrospective study including 5079 patients, recurrent biliary pancreatitis occurred in 23% of patients, with a median time to the next episode of about 186 d, if no intervention was performed[10]. Other biliary events may have occurred in patients who did not receive cholecystectomy after having recovered from an acute episode of biliary pancreatitis, including biliary colic (5.2%-11.8%), acute cholecystitis (1%-5.6%) and cholangitis (0.8%-7%)[19,45-48]. ERCP and sphincterotomy do not protect against the risk of biliary disease[49].

ERCP and sphincterotomy: Patients receiving ERCP and sphincterotomy alone have a risk of developing recurrent pancreatitis ranging from 0% to 8.2%[7,9,10,18,45,48,50] and biliary disease ranging from 0% to 28.6%[10,18,45,50]. Therefore, ERCP and sphincterotomy as definitive treatment in acute severe biliary pancreatitis is at present recommended in patients unfit for cholecystectomy, with severe comorbidity or in necrotizing pancreatitis[5,6,47,48].

Index cholecystectomy: The British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines underline that, in patients with severe acute pancreatitis, cholecystectomy should be postponed until all signs of systemic disorders have resolved[23]. Furthermore, the American College of Gastroenterology guidelines state that, in order to avoid contamination in patients with necrotizing biliary acute pancreatitis, cholecystectomy should be delayed until the inflammatory process has subsided, and fluid collections have resolved or become stable[5].

An increased incidence of contaminated collections is observed when performing early cholecystectomy after moderate to severe pancreatitis[24]. Cholecystectomy is typically delayed in patients with severe acute pancreatitis until a later time during index admission or after discharge, even weeks or months after the pancreatitis episode, or, if pancreatic necrosis is present, cholecystectomy can be performed along with necrosectomy[13,21,22,51].

Initial ERCP and sphincterotomy: In patients who did not undergo cholecystectomy, the risk of recurrent pancreatitis was significant, 8.2% in patients who had ERCP and 17.1% in patients with no intervention, after a median follow-up of 2.3 years[7]. Despite the fact that ERCP substantially prevents recurrent pancreatitis, it does not prevent acute cholecystitis and biliary colic[19]. The value of ERCP in patients with acute biliary pancreatitis and concomitant cholangitis is well recognized[5,6,25,33], whereas, the role and timing of ERCP with sphincterotomy in patients with predicted severe biliary pancreatitis without cholangitis or a high suspicion of a persistent common bile duct stone remains subject to debate[33].

A recurrent rate of acute biliary pancreatitis, between 0% and 7% was observed in patients who had ERCP and sphincterotomy at index admission but did not receive cholecystectomy[8,19,47,48,50,52]. The risk of recurrent pancreatitis was reduced after sphincterotomy[7,9,19,48,49]. There is ample evidence to support the belief that sphincterotomy at index admission with interval cholecystectomy is a safe and accurate practice and is considered an alternative to index cholecystectomy in patients with severe biliary pancreatitis[13,21,47,48,50,53]. In a retrospective study, no readmissions with recurrent acute pancreatitis or biliary symptoms were observed in patients with severe biliary pancreatitis that had ERCP and sphincterotomy as definitive treatment in patients not fit for cholecystectomy, during median follow-up of 3.1 years[48]. A second retrospective study including patients with moderately severe pancreatitis reported that, after ERCP, no episodes of recurrent pancreatitis were detected while waiting for interval cholecystectomy[47]. Interval laparoscopic cholecystectomy has the potential of recurrent biliary events and additional hospital stay related to a second admission[22,45]. Wilson et al[22] concluded that patients with moderate to severe acute biliary pancreatitis should undergo interval cholecystectomy at a later time, weeks or months after recovering from the initial episode, depending on the patients’ clinical condition, provided the patient underwent ERCP and sphincterotomy at index admission. A large population-based study provided evidence that cholecystectomy and ERCP at index admission were associated with significantly reduced 12-mo readmission rates for acute biliary pancreatitis[8].

Initial interval cholecystectomy: Patients with no fluid collections can undergo cholecystectomy after the inflammatory process has subsided and the clinical condition has improved[13]. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy at index admission is technically demanding and, due to the inflammatory process, it is frequently converted to an open procedure. Interval cholecystectomy probably increases the success rate of laparoscopic cholecystectomy and makes it safer for patients with decreased morbidity[21,24]. Although interval cholecystectomy allows the inflammatory response to resolve, it has been demonstrated that it cannot lessen severe adhesions, elude difficult dissection of the cystic duct and artery in Calot’s triangle, or avoid bleeding, thus resulting in a prolonged operating time[54].

As pseudocyst formation may occur in patients recovering from an acute episode of severe biliary pancreatitis, cholecystectomy can be combined with procedures for internal drainage of pseudocysts if they do not resolve after 6 wk[13], thus avoiding a possible second procedure to drain a pseudocyst[48]. Timing of interval cholecystectomy varies among studies and it has been reported that patients with severe biliary pancreatitis underwent interval cholecystectomy within 6 mo[48]. In a multicenter study including 523 patients with biliary pancreatitis, fewer operative complications during cholecystectomy were observed between 4 and 7 wk after discharge, and higher at index admission up to 2 wk after discharge[55]. Since delaying surgery further than 2 wk after discharge has no apparent unfavorable effect, and delaying definitive management after 12 wk has no prominent advantage, definitive management within 3 mo of admission may decrease recurrent biliary events, readmission rates and operative risk[55]. In patients recovering from an episode of acute pancreatitis and a small pseudocyst with mild symptoms, cholecystectomy can be delayed for a further 3 mo, since spontaneous resolution of the pseudocyst may still occur[56].

Management of pseudocysts and walled-off necrosis according to management plans: Most of the fluid collections generally resolve spontaneously without the need for further intervention, but 5%-16% of patients with severe acute pancreatitis will develop a pseudocyst > 4 wk after onset of pancreatitis[57,58]. The prevalence in biliary pancreatitis is 6%-8%[59]. A pseudocyst will also develop in 8% of patients who have undergone necrosectomy[60]. In a recent prospective multicenter study including 302 patients with acute pancreatitis, pancreatic pseudocysts developed in 6.3% of patients after 4-6 wk. A decrease in size or spontaneous resolution of pseudocysts was observed in an elevated percentage of patients that increased to 84.2% with conservative management[58].

Italian Association for the study of the Pancreas consensus guidelines on severe acute pancreatitis point out that size < 4 cm is a predictor of spontaneous resolution[33]. Furthermore, a prospective study including 369 patients found that prognostic factors for spontaneous resolution of pancreatic pseudocysts after an episode of acute pancreatitis were mild or presented no symptoms and a maximum pseudocyst diameter < 4 cm[56]. A large pseudocyst size itself does not necessitate drainage, although pseudocysts > 6 cm persisting for > 6 wk tend to be symptomatic and have a low likelihood of resolution[11,12]. The American College of Radiology appropriateness criteria in 2009 recommend drainage of complicated pseudocysts ≥ 5 cm that are rapidly enlarging, obstructing, and infected[17]. According to the American College of Gastroenterology guidelines of 2013, asymptomatic pseudocysts and pancreatic or extrapancreatic necrosis regardless of size, location, or extension do not require intervention[5]. The asymptomatic patient is a controversial issue. A wait-and-see policy can be adopted in patients with asymptomatic pseudocysts or minimally symptomatic patients, even after the 6 wk that are required for maturation of a pseudocyst[61,62]. Indications for intervention are symptomatic pseudocysts with persistent pain, nausea and vomiting, or complications, such as infection, gastric or duodenal outlet obstruction, biliary obstruction, rupture and rapidly enlarging cysts[16,63].

Integrity of the main pancreatic duct and awareness of the available techniques help in applying the most appropriate intervention, among endoscopic, surgical and image-guided percutaneous techniques. Pancreatic ductal anatomy is clearly associated with the outcome of pseudocysts managed by percutaneous drainage, with favorable outcomes in patients with normal ducts, and satisfactory outcomes in patients with stricture but no cyst-duct communication[41]. Percutaneous drainage is associated with a high recurrence rate and risk of secondary infection and formation of a pancreatic fistula; thus, it is best applied to infected pseudocysts or patients not suitable for an endoscopic or surgical procedure[64]. Percutaneous drainage alone is associated with therapeutic rates ranging from 14% to 32%, therefore it is usually performed as a temporary measure before endoscopic or surgical management[17,65].

Successful drainage can be achieved with the endoscopic approach in 82%-100% of pancreatic pseudocysts, with complications ranging from 5% to 16% and recurrence rates up to 18%[16,66]. Due to high success rates and low complications rates, the endoscopic approach emerges as the most efficient method. Transpapillary drainage has been used for pancreatic pseudocysts communicating with the main pancreatic duct but it is associated with ERCP-related complications, contamination of the pseudocyst, and insufficient drainage of large cysts[16,61]. Pseudocysts > 4 cm require transmural drainage, preferably with EUS guidance but conventional endoscopy also offers good results[61]. Transmural drainage has gradually become the preferred therapeutic approach for managing pseudocysts, including the advantages of cystogastrostomy or cystoduodenostomy (internal drainage)[16]. A recent multicenter retrospective study found that transpapillary drainage of pseudocysts in patients undergoing EUS-guided transmural drainage added no benefit to outcomes and adversely affected resolution of the pseudocyst[67].

Transmural drainage can be carried out either by direct endoscopy or by EUS guidance. Endoscopy by EUS guidance is increasingly used in particular for pseudocysts in which there is no definitive luminal bulge, or when managing patients with portal hypertension or coagulopathy[68]. A recent systematic review reported mean technical and clinical success rates of 97% and 90%, respectively, mean overall recurrence rate of 8%, and overall complication rate of 17% for EUS-guided drainage[69]. A meta-analysis comparing EUS-guided drainage with conventional transmural drainage for pseudocyst found that technical success rate was significantly higher for EUS-guided drainage but not superior to conventional transmural drainage in terms of short- and long-term success, and overall complications were similar in both groups[70]. A randomized trial comparing patients undergoing EUS-guided drainage with conventional transmural drainage for pseudocysts found a technical success rate of 100% and 33%, respectively[71]. A second randomized trial also found a higher technical success rate for patients undergoing EUS-guided drainage than for conventional endoscopic drainage (94% vs 72%)[72]. While high clinical success rates have been reported when draining pseudocysts with endoscopic procedures, clinical success rates for walled-off necrosis are relatively poor due to the presence of solid material. Multiple transluminal gateway treatment is suggested for walled-off necrosis, thus avoiding the need for surgery or endoscopic necrosectomy[73] or other more complex procedures. Endoscopic procedures for pseudocyst drainage are technically feasible only if access to the pseudocyst through the gastric or duodenal wall can be achieved; at present performance of an endoscopic cystjejunostomy is not possible. Patients requiring more complex management of their pseudocyst are not candidates for endoscopic procedures. Another limitation of the endoscopic approach is the inability to perform an additional cholecystectomy when necessary, as patients with biliary pancreatitis require open or laparoscopic cholecystectomy[4].

Surgical cystogastrostomy or cystojejunostomy has been the traditional approach for pseudocyst management and is still the preferred treatment in most centers with a success rate of 94%-99%[4,74]. Open or laparoscopic surgical drainage should be applied after failure of endoscopic methods, for recurrence after a successful endoscopic drainage, and in patients who do not meet the criteria for endoscopic or percutaneous drainage[38]. Moreover, percutaneous and endoscopic techniques, if not therapeutic, can serve as a bridge to surgery and improve patients’ local and general condition[24]. Laparoscopy is a minimally invasive method that achieves sufficient internal drainage and debridement of necrotic tissue, with good results and minimal morbidity[75]. In a large series on laparoscopic cystogastrostomy, the authors conclude that laparoscopy has a significant role in the surgical management of pseudocysts, with favorable outcomes[51]. A retrospective study and a randomized trial, both by Varadarajulu et al[74,76], comparing EUS-guided drainage with open surgical cystogastrostomy found no significant difference in pseudocyst recurrence between the two groups. A drawback of these studies is the implementation of open surgery.

In patients with pseudocysts who have recovered from an acute episode of moderate to severe biliary pancreatitis, interval cholecystectomy should be delayed until the pseudocyst resolves. If it persists for > 6 wk, operative pseudocyst drainage can be performed safely at this time with concurrent cholecystectomy, thus minimizing the risk for a second interventional procedure[24].

The following alternatives are feasible for the treatment of patients fit for surgery: index cholecystectomy, interval cholecystectomy, ERCP and endoscopic sphincterotomy followed by delayed cholecystectomy. Cholecystectomy is an essential part of dealing with patients with severe biliary pancreatitis. Current guidelines recommend delaying cholecystectomy until resolution of inflammatory process has occurred, usually not earlier than 6 wk after onset of acute pancreatitis. It seems that ERCP and endoscopic sphincterotomy protect patients better than interval cholecystectomy for recurrent pancreatitis and biliary episodes, while at the same time providing more time for the potential pseudocyst either to resolve or become stable for intervention. The optimal time point for applying any available pseudocyst treatment modality is > 6 wk. Recent trends in management of pseudocysts involve minimally invasive therapeutic techniques, but surgical approaches are still frequently used, especially if combined with cholecystectomy at the appropriate time. EUS and MRCP with secretin are reliable tools for tailored patient therapy. In patients unfit for surgery, the application of ERCP and endoscopic sphincterotomy has better results than conservative management.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Greece

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Gkekas I, Hauser G, Joliat GR S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Kerr C E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Tse F, Yuan Y. Early routine endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography strategy versus early conservative management strategy in acute gallstone pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;CD009779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4932] [Cited by in RCA: 4269] [Article Influence: 355.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (44)] |

| 3. | Johnson CD, Abu-Hilal M. Persistent organ failure during the first week as a marker of fatal outcome in acute pancreatitis. Gut. 2004;53:1340-1344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 436] [Cited by in RCA: 408] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Melman L, Azar R, Beddow K, Brunt LM, Halpin VJ, Eagon JC, Frisella MM, Edmundowicz S, Jonnalagadda S, Matthews BD. Primary and overall success rates for clinical outcomes after laparoscopic, endoscopic, and open pancreatic cystgastrostomy for pancreatic pseudocysts. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:267-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tenner S, Baillie J, DeWitt J, Vege SS. American College of Gastroenterology guideline: management of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1400-115; 1416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1232] [Cited by in RCA: 1372] [Article Influence: 114.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 6. | Working Group IAP/APA Acute Pancreatitis Guidelines. IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2013;13:e1-e15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1080] [Cited by in RCA: 1019] [Article Influence: 84.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 7. | Hwang SS, Li BH, Haigh PI. Gallstone pancreatitis without cholecystectomy. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:867-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nguyen GC, Rosenberg M, Chong RY, Chong CA. Early cholecystectomy and ERCP are associated with reduced readmissions for acute biliary pancreatitis: a nationwide, population-based study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:47-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | El-Dhuwaib Y, Deakin M, David GG, Durkin D, Corless DJ, Slavin JP. Definitive management of gallstone pancreatitis in England. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2012;94:402-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mustafa A, Begaj I, Deakin M, Durkin D, Corless DJ, Wilson R, Slavin JP. Long-term effectiveness of cholecystectomy and endoscopic sphincterotomy in the management of gallstone pancreatitis. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:127-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bradley EL, Gonzalez AC, Clements JL. Acute pancreatic pseudocysts: incidence and implications. Ann Surg. 1976;184:734-737. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Yeo CJ, Bastidas JA, Lynch-Nyhan A, Fishman EK, Zinner MJ, Cameron JL. The natural history of pancreatic pseudocysts documented by computed tomography. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1990;170:411-417. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Larson SD, Nealon WH, Evers BM. Management of gallstone pancreatitis. Adv Surg. 2006;40:265-284. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Kolh P, De Hert S, De Rango P. The Concept of Risk Assessment and Being Unfit for Surgery. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2016;51:857-866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Moonesinghe SR, Mythen MG, Das P, Rowan KM, Grocott MP. Risk stratification tools for predicting morbidity and mortality in adult patients undergoing major surgery: qualitative systematic review. Anesthesiology. 2013;119:959-981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 21.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Muthusamy VR, Chandrasekhara V, Acosta RD, Bruining DH, Chathadi KV, Eloubeidi MA, Faulx AL, Fonkalsrud L, Gurudu SR, Khashab MA, Kothari S, Lightdale JR, Pasha SF, Saltzman JR, Shaukat A, Wang A, Yang J, Cash BD, DeWitt JM. The role of endoscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory pancreatic fluid collections. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:481-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lorenz JM, Funaki BS, Ray CE, Brown DB, Gemery JM, Greene FL, Kinney TB, Kostelic JK, Millward SF, Nemcek AA. ACR Appropriateness Criteria on percutaneous catheter drainage of infected fluid collections. J Am Coll Radiol. 2009;6:837-843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bignell M, Dearing M, Hindmarsh A, Rhodes M. ERCP and endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES): a safe and definitive management of gallstone pancreatitis with the gallbladder left in situ. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:2205-2210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | van Baal MC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ, van Santvoort HC, Schaapherder AF, Nieuwenhuijs VB, Gooszen HG, van Ramshorst B, Boerma D. Timing of cholecystectomy after mild biliary pancreatitis: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2012;255:860-866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Trna J, Vege SS, Pribramska V, Chari ST, Kamath PS, Kendrick ML, Farnell MB. Lack of significant liver enzyme elevation and gallstones and/or sludge on ultrasound on day 1 of acute pancreatitis is associated with recurrence after cholecystectomy: a population-based study. Surgery. 2012;151:199-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Uhl W, Müller CA, Krähenbühl L, Schmid SW, Schölzel S, Büchler MW. Acute gallstone pancreatitis: timing of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in mild and severe disease. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:1070-1076. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Wilson CT, de Moya MA. Cholecystectomy for acute gallstone pancreatitis: early vs delayed approach. Scand J Surg. 2010;99:81-85. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Working Party of the British Society of Gastroenterology; Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland; Pancreatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland; Association of Upper GI Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland. UK guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Gut. 2005;54 Suppl 3:iii1-iii9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 330] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nealon WH, Bawduniak J, Walser EM. Appropriate timing of cholecystectomy in patients who present with moderate to severe gallstone-associated acute pancreatitis with peripancreatic fluid collections. Ann Surg. 2004;239:741-749; discussion 749-751. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Forsmark CE, Baillie J. AGA Institute technical review on acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2022-2044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 494] [Cited by in RCA: 503] [Article Influence: 27.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Frossard JL, Hadengue A, Amouyal G, Choury A, Marty O, Giostra E, Sivignon F, Sosa L, Amouyal P. Choledocholithiasis: a prospective study of spontaneous common bile duct stone migration. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:175-179. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Williams EJ, Taylor S, Fairclough P, Hamlyn A, Logan RF, Martin D, Riley SA, Veitch P, Wilkinson ML, Williamson PR. Risk factors for complication following ERCP; results of a large-scale, prospective multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2007;39:793-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 268] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1716] [Cited by in RCA: 1681] [Article Influence: 58.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 29. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Maple JT, Ben-Menachem T, Anderson MA, Appalaneni V, Banerjee S, Cash BD, Fisher L, Harrison ME, Fanelli RD, Fukami N, Ikenberry SO, Jain R, Khan K, Krinsky ML, Strohmeyer L, Dominitz JA. The role of endoscopy in the evaluation of suspected choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 380] [Cited by in RCA: 328] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 30. | da Costa DW, Schepers NJ, Römkens TE, Boerma D, Bruno MJ, Bakker OJ. Endoscopic sphincterotomy and cholecystectomy in acute biliary pancreatitis. Surgeon. 2016;14:99-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Garrow D, Miller S, Sinha D, Conway J, Hoffman BJ, Hawes RH, Romagnuolo J. Endoscopic ultrasound: a meta-analysis of test performance in suspected biliary obstruction. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:616-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Romagnuolo J, Bardou M, Rahme E, Joseph L, Reinhold C, Barkun AN. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography: a meta-analysis of test performance in suspected biliary disease. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:547-557. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Pezzilli R, Zerbi A, Campra D, Capurso G, Golfieri R, Arcidiacono PG, Billi P, Butturini G, Calculli L, Cannizzaro R. Consensus guidelines on severe acute pancreatitis. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:532-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Savides TJ. EUS-guided ERCP for patients with intermediate probability for choledocholithiasis: is it time for all of us to start doing this? Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:669-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Anderloni A, Repici A. Role and timing of endoscopy in acute biliary pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:11205-11208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Fusaroli P, Kypraios D, Caletti G, Eloubeidi MA. Pancreatico-biliary endoscopic ultrasound: a systematic review of the levels of evidence, performance and outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4243-4256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Pelaez-Luna M, Vege SS, Petersen BT, Chari ST, Clain JE, Levy MJ, Pearson RK, Topazian MD, Farnell MB, Kendrick ML. Disconnected pancreatic duct syndrome in severe acute pancreatitis: clinical and imaging characteristics and outcomes in a cohort of 31 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:91-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Guenther L, Hardt PD, Collet P. Review of current therapy of pancreatic pseudocysts. Z Gastroenterol. 2015;53:125-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Ramia JM, Fabregat J, Pérez-Miranda M, Figueras J. [Disconnected panreatic duct syndrome]. Cir Esp. 2014;92:4-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Andrén-Sandberg A, Dervenis C. Pancreatic pseudocysts in the 21st century. Part I: classification, pathophysiology, anatomic considerations and treatment. JOP. 2004;5:8-24. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Nealon WH, Walser E. Main pancreatic ductal anatomy can direct choice of modality for treating pancreatic pseudocysts (surgery versus percutaneous drainage). Ann Surg. 2002;235:751-758. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Tirkes T, Sandrasegaran K, Sanyal R, Sherman S, Schmidt CM, Cote GA, Akisik F. Secretin-enhanced MR cholangiopancreatography: spectrum of findings. Radiographics. 2013;33:1889-1906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Nealon WH, Walser E. Surgical management of complications associated with percutaneous and/or endoscopic management of pseudocyst of the pancreas. Ann Surg. 2005;241:948-957; discussion 957-960. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Alimoglu O, Ozkan OV, Sahin M, Akcakaya A, Eryilmaz R, Bas G. Timing of cholecystectomy for acute biliary pancreatitis: outcomes of cholecystectomy on first admission and after recurrent biliary pancreatitis. World J Surg. 2003;27:256-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Ito K, Ito H, Whang EE. Timing of cholecystectomy for biliary pancreatitis: do the data support current guidelines? J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:2164-2170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Cameron DR, Goodman AJ. Delayed cholecystectomy for gallstone pancreatitis: re-admissions and outcomes. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2004;86:358-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Heider TR, Brown A, Grimm IS, Behrns KE. Endoscopic sphincterotomy permits interval laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients with moderately severe gallstone pancreatitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Sanjay P, Yeeting S, Whigham C, Judson H, Polignano FM, Tait IS. Endoscopic sphincterotomy and interval cholecystectomy are reasonable alternatives to index cholecystectomy in severe acute gallstone pancreatitis (GSP). Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1832-1837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | van Geenen EJ, van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, van der Peet DL, van Erpecum KJ, Fockens P, Mulder CJ, Bruno MJ. Lack of consensus on the role of endoscopic retrograde cholangiography in acute biliary pancreatitis in published meta-analyses and guidelines: a systematic review. Pancreas. 2013;42:774-780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Kaw M, Al-Antably Y, Kaw P. Management of gallstone pancreatitis: cholecystectomy or ERCP and endoscopic sphincterotomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:61-65. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Palanivelu C, Senthilkumar K, Madhankumar MV, Rajan PS, Shetty AR, Jani K, Rangarajan M, Maheshkumaar GS. Management of pancreatic pseudocyst in the era of laparoscopic surgery--experience from a tertiary centre. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:2262-2267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Ong SK, Christie PM, Windsor JA. Management of gallstone pancreatitis in Auckland: progress and compliance. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:194-199. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Hernandez V, Pascual I, Almela P, Añon R, Herreros B, Sanchiz V, Minguez M, Benages A. Recurrence of acute gallstone pancreatitis and relationship with cholecystectomy or endoscopic sphincterotomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2417-2423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Schachter P, Peleg T, Cohen O. Interval laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the management of acute biliary pancreatitis. HPB Surg. 2000;11:319-322; discussion 322-323. [PubMed] |

| 55. | Johnstone M, Marriott P, Royle TJ, Richardson CE, Torrance A, Hepburn E, Bhangu A, Patel A, Bartlett DC, Pinkney TD. The impact of timing of cholecystectomy following gallstone pancreatitis. Surgeon. 2014;12:134-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Lankisch PG, Weber-Dany B, Maisonneuve P, Lowenfels AB. Pancreatic pseudocysts: prognostic factors for their development and their spontaneous resolution in the setting of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2012;12:85-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Maringhini A, Uomo G, Patti R, Rabitti P, Termini A, Cavallera A, Dardanoni G, Manes G, Ciambra M, Laccetti M. Pseudocysts in acute nonalcoholic pancreatitis: incidence and natural history. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:1669-1673. [PubMed] |

| 58. | Cui ML, Kim KH, Kim HG, Han J, Kim H, Cho KB, Jung MK, Cho CM, Kim TN. Incidence, risk factors and clinical course of pancreatic fluid collections in acute pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:1055-1062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Imrie CW, Buist LJ, Shearer MG. Importance of cause in the outcome of pancreatic pseudocysts. Am J Surg. 1988;156:159-162. [PubMed] |

| 60. | Connor S, Alexakis N, Raraty MG, Ghaneh P, Evans J, Hughes M, Garvey CJ, Sutton R, Neoptolemos JP. Early and late complications after pancreatic necrosectomy. Surgery. 2005;137:499-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Samuelson AL, Shah RJ. Endoscopic management of pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2012;41:47-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Kim KO, Kim TN. Acute pancreatic pseudocyst: incidence, risk factors, and clinical outcomes. Pancreas. 2012;41:577-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Jacobson BC, Baron TH, Adler DG, Davila RE, Egan J, Hirota WK, Leighton JA, Qureshi W, Rajan E, Zuckerman MJ. ASGE guideline: The role of endoscopy in the diagnosis and the management of cystic lesions and inflammatory fluid collections of the pancreas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:363-370. [PubMed] |

| 64. | Bhattacharya D, Ammori BJ. Minimally invasive approaches to the management of pancreatic pseudocysts: review of the literature. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2003;13:141-148. [PubMed] |

| 65. | Tyberg A, Karia K, Gabr M, Desai A, Doshi R, Gaidhane M, Sharaiha RZ, Kahaleh M. Management of pancreatic fluid collections: A comprehensive review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:2256-2270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Pan G, Wan MH, Xie KL, Li W, Hu WM, Liu XB, Tang WF, Wu H. Classification and Management of Pancreatic Pseudocysts. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Yang D, Amin S, Gonzalez S, Mullady D, Hasak S, Gaddam S, Edmundowicz SA, Gromski MA, DeWitt JM, El Zein M. Transpapillary drainage has no added benefit on treatment outcomes in patients undergoing EUS-guided transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts: a large multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:720-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Kahaleh M, Shami VM, Conaway MR, Tokar J, Rockoff T, De La Rue SA, de Lange E, Bassignani M, Gay S, Adams RB. Endoscopic ultrasound drainage of pancreatic pseudocyst: a prospective comparison with conventional endoscopic drainage. Endoscopy. 2006;38:355-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Fabbri C, Luigiano C, Lisotti A, Cennamo V, Virgilio C, Caletti G, Fusaroli P. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided treatments: are we getting evidence based--a systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:8424-8448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Panamonta N, Ngamruengphong S, Kijsirichareanchai K, Nugent K, Rakvit A. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided versus conventional transmural techniques have comparable treatment outcomes in draining pancreatic pseudocysts. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:1355-1362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Varadarajulu S, Christein JD, Tamhane A, Drelichman ER, Wilcox CM. Prospective randomized trial comparing EUS and EGD for transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:1102-1111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Park DH, Lee SS, Moon SH, Choi SY, Jung SW, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided versus conventional transmural drainage for pancreatic pseudocysts: a prospective randomized trial. Endoscopy. 2009;41:842-848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Varadarajulu S, Phadnis MA, Christein JD, Wilcox CM. Multiple transluminal gateway technique for EUS-guided drainage of symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:74-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Varadarajulu S, Bang JY, Sutton BS, Trevino JM, Christein JD, Wilcox CM. Equal efficacy of endoscopic and surgical cystogastrostomy for pancreatic pseudocyst drainage in a randomized trial. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:583-590.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 325] [Article Influence: 27.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 75. | Vilmann AS, Menachery J, Tang SJ, Srinivasan I, Vilmann P. Endosonography guided management of pancreatic fluid collections. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:11842-11853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Varadarajulu S, Lopes TL, Wilcox CM, Drelichman ER, Kilgore ML, Christein JD. EUS versus surgical cyst-gastrostomy for management of pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:649-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |