Published online Feb 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i5.1357

Revised: July 9, 2013

Accepted: July 17, 2013

Published online: February 7, 2014

Celiac disease is a chronic, immune-mediated enteropathy caused by a permanent sensitivity to ingested gluten cereals that develops in genetically susceptible individuals. The classic presentation of celiac disease includes symptoms of malabsorption but has long been associated with cognitive, emotional, and behavioral disorders. We describe an 8-year-old patient with non-scarring alopecia and diagnosed with trichotillomania. Furthermore, she presented with a 3-year history of poor appetite and two or three annual episodes of mushy, fatty stools. Laboratory investigations showed a normal hemoglobin concentration and a low ferritin level. Serologic studies showed an elevated tissue immunoglobulin G anti-tissue transglutaminase level. A duodenal biopsy showed subtotal villous atrophy and crypt hyperplasia, and a large gastric trichobezoar was found in the stomach. Immediately after beginning a gluten-free diet, complete relief of trichotillomania and trichophagia was achieved. In this report, we describe a behavioral disorder as a primary phenomenon of celiac disease, irrespective of nutritional status.

Core tip: Celiac disease has been associated with trichotillomania and trichophagia but is always secondary to iron deficiency anemia. We describe a behavioral disorder as a primary phenomenon of celiac disease, irrespective of nutritional status.

- Citation: Irastorza I, Tutau C, Vitoria JC. A trichobezoar in a child with undiagnosed celiac disease: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(5): 1357-1360

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i5/1357.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i5.1357

A trichobezoar is a mass of hair found in the stomach[1] or, less commonly, in the small bowel (Rapunzel syndrome)[2]. This rare condition is nearly exclusively observed in young females. One should be aware of a trichobezoar in young females with psychiatric comorbidity, as this condition is usually the result of the urge to pull out one’s own hair (trichotillomania) and swallow it (trichophagia). Human hair is resistant to digestion and peristalsis due to its smooth surface. Hair therefore accumulates among the mucosal folds of the stomach. The continuous ingestion of hair together with mucus and food can cause impaction, leading to the formation of a trichobezoar[3].

Trichobezoars may not be recognized in the early stages due to their non-specific presentation or even lack of symptoms. When unrecognized, a trichobezoar continues to grow in size and weight due to the continued ingestion of hair. This growth increases the risk of severe complications, such as gastric mucosal erosion, ulceration, and even perforation of the stomach or the small intestine. In addition, intussusception, obstructive jaundice, protein-losing enteropathy, pancreatitis, and even death have been reported in the literature as complications of (unrecognized) trichobezoars[3].

Celiac disease (CD OMIM 212750) is an immune-mediated systemic disorder elicited by gluten and related prolamines in genetically susceptible individuals and characterized by the presence of a variable combination of gluten-dependent clinical manifestations, CD-specific antibodies, an human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 haplotype, and enteropathy. CD-specific antibodies comprise autoantibodies against transglutaminase 2, including endomysial antibodies, and antibodies against deamidated forms of gliadin peptides[4]. This disease is one of the most common lifelong disorders affecting Caucasians. Recent studies have estimated a prevalence of CD close to 1:120[5].

The clinical presentation depends on age, sensitivity to gluten, and the amount of gluten ingested in the diet and on unknown factors. CD has highly variable clinical expression. The classical presentation of CD is characterized by steatorrhea, abdominal distension, and edema, but constitutional symptoms, such as lethargy, poor appetite, depression, and emotional disorders, are frequently present. Iron and folate deficiencies are commonly found, either in isolation or as a feature, and may occur with or without anemia[6].

There are still insufficient data on the association of CD with various neurological disorders in children, adolescents, and young adults, including certain common and “soft” neurological conditions, such as headache, learning disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and tic disorders[7]. Pica may be a symptom of numerous childhood conditions, including CD[8], and children with this condition require careful diagnostic evaluation.

Only three articles reporting the association of CD and trichobezoars have been found in the medical literature[9-11]. A new case of this rare association is reported.

An 8-year-old girl suffering from mild non-scarring alopecia was referred by her pediatrician to a dermatologist. The girl was diagnosed with trichotillomania. Together with this finding, the girl presented with a 3-year history of poor appetite; irritability; clinginess; and two or three annual episodes of mushy, fatty stools. These episodes lasted for one month at most, with normal stools in the meantime. She had a significantly slowed rate of weight and growth during this period. Serologic studies for celiac disease were abnormal, and the girl was therefore referred to the Department of Paediatric Gastroenterology. She weighed 19.5 kg (3rd percentile for age), and her height was 116 cm (below 3rd percentile for age). Her examination revealed pallor, thin hair, areas of alopecia, a decreased subcutaneous adipose layer, muscular hypoplasia, and abdominal distension.

At admission, laboratory investigations showed a normal hemoglobin concentration of 10.9 g/dL [normal range (NR) 10.7-14.8 g/dL], a normal red cell count and hematocrit, mild microcytosis (69.2 fL, NR 73-94 fL), and a normal white cell and platelet count. Iron at 18 mg/dL, ferritin at 10 ng/mL (NR 12-150 ng/mL), transferrin at 348 mg/dL (NR 200-380 mg/dL), and transferrin saturation at 4.1% (NR 20%-40%) were found in ferrokinetic studies. Further investigation revealed an elevated serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase level at 93 U/L (NR 7-50 U/L) and a glutamic pyruvic transaminase level at 114 U/L (NR 5-47 U/L), with normal clotting tests.

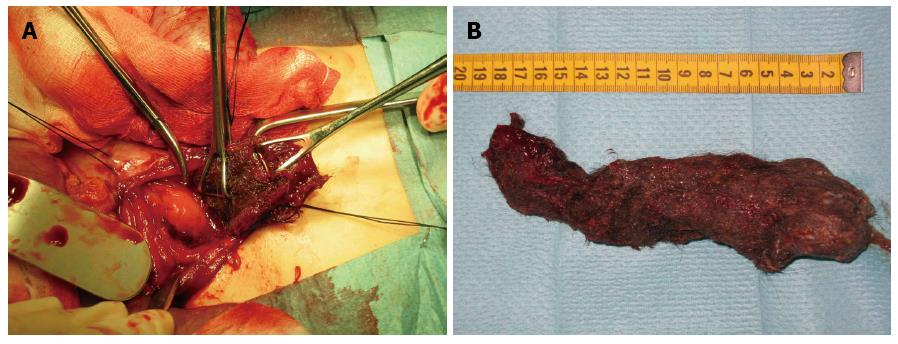

Serologic studies were repeated and showed a tissue IgA anti-tissue transglutaminase level of 989 U/mL (Celikey®, Phadia, Uppsala, Sweden). To confirm the suspicion of CD, an intestinal biopsy was indicated. A first attempt was performed with a Crosby Capsule, as it was impossible to enter the gastric chamber. An upper endoscopy was performed, and a large gastric trichobezoar was found in the stomach. Attempts to remove the bezoar were unsuccessful, so laparotomy and gastrotomy were therefore performed. By the gastrotomy, a 19 cm by 8 cm gastric bezoar was removed (Figure 1). Duodenal biopsies were obtained to confirm CD. The postoperative course was uneventful.

The patient’s duodenal biopsies showed changes consistent with gluten-sensitive enteropathy, including subtotal villous atrophy and crypt hyperplasia (Marsh-Oberhuber 3c). The histological findings, positive tissue IgA anti-tissue transglutaminase antibody testing, and clinical features supported the presumptive diagnosis of CD.

Supplementary iron and a gluten-free diet were instituted. Complete relief of trichotillomania and trichophagia was immediately achieved after the withdrawal of gluten. The excellent response to treatment confirmed the diagnosis of CD. After the patient had been on a gluten-free diet for 6 mo, the antibody levels normalized. Further serologic studies performed to monitor treatment adherence were repeatedly negative. During clinical follow-up, the patient remained asymptomatic, reaching the 50th percentile in weight and height. The control biopsies obtained 2 years after the diagnosis showed a normal intestinal mucosa. After following a gluten-free diet for 4 years, the patient remains asymptomatic, without trichotillomania episodes or other behavioral disorders.

Trichotillomania is the morbid craving to pull out hair from the scalp or other parts of the body and is frequently associated with trichophagia, the compulsion to eat hair. This habit is more often observed in girls during the first two decades of life[3]. Trichophagia is one of the various forms of pica (the compulsion to eat non-nutritious substances). The most common underlying conditions associated with pica are mineral deficiency (typically, iron deficiency) and mental health conditions (such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, schizophrenia, and autism). The development of a trichobezoar due to the ingestion of pulled hair is a salient complication.

CD has long been associated with cognitive, emotional, and neurodegenerative disorders, including cerebellar ataxia, peripheral neuropathy, epilepsy, dementia, and depression. One study reported a prior history of psychiatric treatment in a high proportion of adults who were newly diagnosed with CD, even years before the diagnosis[12]. Furthermore, other more frequent neurological manifestations are being researched and may be related to this disease, such as headache, learning disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and tic disorders[7].

The mechanisms involved in the etiology and pathogenesis of mental and behavioral disorders related to CD are unclear. The cumulative effect of nutritional, inflammatory, or immunologic factors may play a certain role in these manifestations[7]. There are several pathways through acids, and especially tryptophan, may lead to disturbances in central nervous-system serotonin which CD can influence the central nervous system and predispose an individual to mental disorders. Malabsorption of important nutrients, such as folic acid, vitamin B6, and amino function that are associated with depression and aggressive behavior[13].

Case reports on the association of CD and trichophagia have been previously described by three authors[10-12]. In the three patients described, iron deficiency anemia due to intestinal malabsorption appeared to be the primary phenomenon, leading to pica and therefore to trichobezoar formation. There are no reports of pica in patients with CD without anemia.

In this patient, CD presented with severe emotional symptoms. Iron deficiency was detected, but the hemoglobin level was within the normal range. In this patient, trichotillomania was more likely due to behavioral disorders secondary to CD rather than due to the iron deficiency. The fact that this habit disappeared immediately after instituting a gluten-free diet supports this theory.

P- Reviewers: Balaban YH, Ciaccio EJ, Ciacci C, Jadallah KA S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Sehgal VN, Srivastava G. Trichotillomania +/- trichobezoar: revisited. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:911-915. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Vaughan ED, Sawyers JL, Scott HW. The Rapunzel syndrome. An unusual complication of intestinal bezoar. Surgery. 1968;63:339-343. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Gorter RR, Kneepkens CM, Mattens EC, Aronson DC, Heij HA. Management of trichobezoar: case report and literature review. Pediatr Surg Int. 2010;26:457-463. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabó IR, Mearin ML, Phillips A, Shamir R, Troncone R, Giersiepen K, Branski D, Catassi C. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition guidelines for the diagnosis of coeliac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;54:136-160. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Castaño L, Blarduni E, Ortiz L, Núñez J, Bilbao JR, Rica I, Martul P, Vitoria JC. Prospective population screening for celiac disease: high prevalence in the first 3 years of life. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;39:80-84. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Dewar DH, Ciclitira PJ. Clinical features and diagnosis of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:S19-S24. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Zelnik N, Pacht A, Obeid R, Lerner A. Range of neurologic disorders in patients with celiac disease. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1672-1676. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Korman SH. Pica as a presenting symptom in childhood celiac disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;51:139-141. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Larsson LT, Nivenius K, Wettrell G. Trichobezoar in a child with concomitant coeliac disease: a case report. Acta Paediatr. 2004;93:278-280. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Marcos Alonso S, Bravo Mata M, Bautista Casasnova A, Pavón Belinchón P, Monasterio Corral L. Gastric trichobezoar as an atypical form of presentation of celiac disease. An Pediatr (Barc). 2005;62:601-602. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | McCallum IJ, Van zanten C, Inam IZ, Craig W, Mahdi G, Thompson RJ. Trichobezoar in a child with undiagnosed coeliac disease. J Paediatr Child Health. 2008;44:524-525. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Hallert C, Derefeldt T. Psychic disturbances in adult coeliac disease. I. Clinical observations. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1982;17:17-19. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Voĭtenko MF. Problems in the command activities of the evacuation distributing centers during World War II. Voen Med Zh. 1990;16-19. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |