Published online Dec 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i45.17254

Revised: April 21, 2014

Accepted: July 24, 2014

Published online: December 7, 2014

Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome (BRBNS) is a rare disease characterized by multiple venous malformations and hemangiomas in the skin and visceral organs. The lesions often involve the cutaneous and gastrointestinal systems. Other organs can also be involved, such as the central nervous system, liver, and muscles. The most common symptoms are gastrointestinal bleeding and secondary iron deficiency anemia. The syndrome may also present with severe complications such as rupture, intestinal torsion, and intussusception, and can even cause death. Cutaneous malformations are usually asymptomatic and do not require treatment. The treatment of gastrointestinal lesions is determined by the extent of intestinal involvement and severity of the disease. Most patients respond to supportive therapy, such as iron supplementation and blood transfusion. For more significant hemorrhages or severe complications, surgical resection, endoscopic sclerosis, and laser photocoagulation have been proposed. Here we present a case of BRBNS in a 45-year-old woman involving 16 sites including the scalp, eyelid, orbit, lip, tongue, face, back, upper and lower limbs, buttocks, root of neck, clavicle area, superior mediastinum, glottis, esophagus, colon, and anus, with secondary severe anemia. In addition, we summarize the epidemiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, differential diagnosis and therapies of this disease by analyzing all previously reported cases to enhance the awareness of this syndrome.

Core tip: We present a case of blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome (BRBNS). This is the 12th Chinese patient and the first female from the Chinese Mainland reported in the English literature. BRBNS is a rare disease characterized by multiple venous malformations and hemangiomas in the skin and visceral organs. The most common symptoms are gastrointestinal bleeding and secondary iron deficiency anemia. We summarize the epidemiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, differential diagnosis and therapies of the disease. In a patient with gastrointestinal bleeding and multiple hemangiomas, a diagnosis of BRBNS should be considered and a systemic examination is necessary. An early diagnosis will improve the patient’s quality of life.

- Citation: Jin XL, Wang ZH, Xiao XB, Huang LS, Zhao XY. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: A case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(45): 17254-17259

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i45/17254.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i45.17254

Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome (BRBNS or Bean’s syndrome) was first recognized by Gascoyen[1] in 1860, and 100 years later Bean[2] described BRBNS in detail and coined the term Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome. The incidence of reported BRBNS is very low[3]. A MEDLINE search yielded approximately 200 case reports published to date. Wong and Lau[4] reported the first Chinese patient diagnosed with BRBNS in 1982. We report a case of BRBNS in a 45-year-old woman with gastrointestinal bleeding and severe anemia. Lesions were found in many areas including the skin and superior mediastinum. This is the 12th Chinese patient and the first female from the Chinese Mainland reported in the English literature.

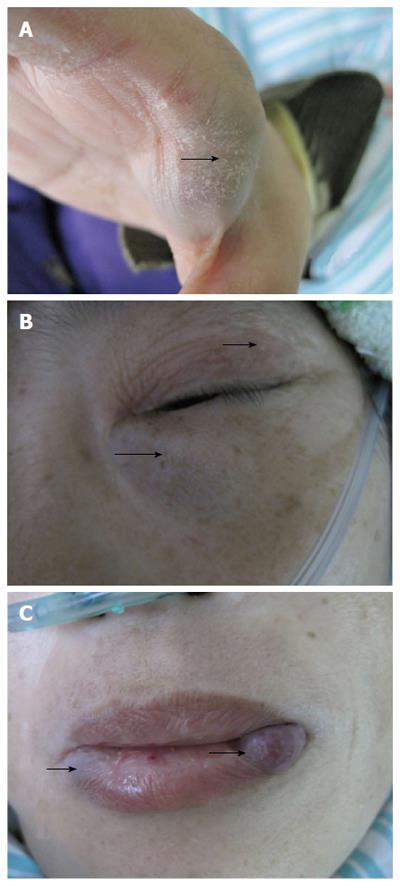

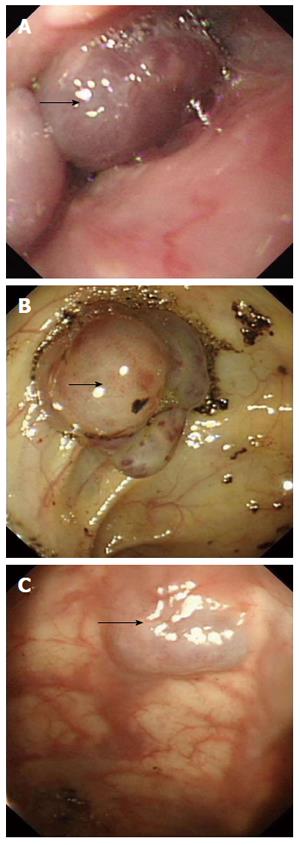

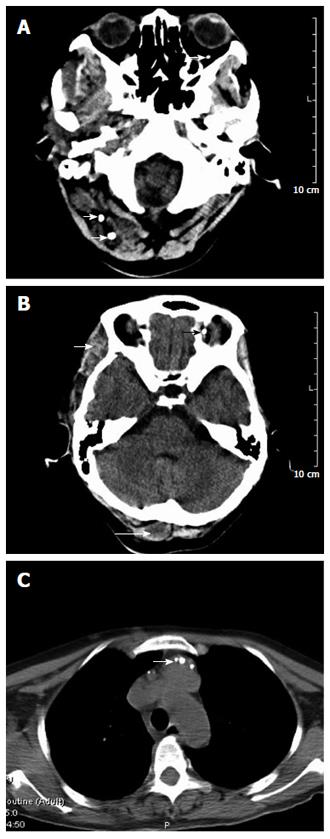

A 45-year-old female patient was admitted because of pallor and fatigue. She was born with grain of rice-sized cutaneous bluish nodules on her left eyelid. Since then the patient experienced recurrences of bluish nodules in the skin, which had increased in size and in number over time. She had no discomfort and had never attended hospital. Five years ago, she suffered from pallor and fatigue and attended a local hospital where a diagnosis of angioma and iron deficiency anemia (IDA) was made. Recently, the symptoms were aggravated, and the patient visited our hospital for further diagnosis and treatment. She denied having melena, hematochezia, menorrhagia, bleeding gums or recurrent epistaxis, hemoptysis, hematemesis, dyspnea, and stomachache. The patient had no history of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, peptic ulcer or chronic liver disease, and no family history of recurrent skin lesions or gastrointestinal bleeding. Physical examination showed pallor of the conjunctiva, pale lips, bluish nodules on upper and lower limbs (Figure 1A), eyelid (Figure 1B), lips (Figure 1C), tongue, face, back, and buttocks, which were soft, tender and hemorrhagic, easily compressible and promptly refilled after compression. The size of the lesions varied from 0.5-3.0 cm. The abdomen was soft and non-tender. Laboratory findings were as follows. Routine blood analysis showed severe anemia (hemoglobin 3.6 g/dL), characterized by small cells and low pigment (mean corpuscular volume 25 pg, and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration 35 g/dL). White blood cell was 4.0 × 109/L and platelet count was 169 × 109/L. Serum ferritin level was 9 ng/mL. Serum blood urea nitrogen was 9.7 mg/dL, creatinine 0.58 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase 7 IU/L, and Alanine aminotransferase 16 IU/L. Fecal occult blood test was positive. Bone marrow aspiration revealed myeloid hyperactivity and normocellular marrow with minimal erythroids. Bone marrow iron stores were depleted (marrow iron stain showed extracellular iron (+), sideroblasts 10%). The results indicated that the patient was suffering from IDA. On endoscopy, the glottis and esophagus (Figure 2A) showed multiple bluish hemangiomas, and no bleeding was seen. One lesion (2.0 cm × 2.5 cm) was found in the colon (Figure 2B) with no fresh bleeding, and lesions were also observed in the anus (Figure 2C). A head computed tomography (CT) (Figure 3A and B) showed lesions on the scalp, left tempora, orbit, and the brain was normal. On chest CT (Figure 3C), the root of the neck, clavicle area and superior mediastinum showed multiple nodular, lumpish lesions, and a soft tissue component that was consistent with a vascular malformation and hemic calculus. Abdominal ultrasonography was normal. On the basis of the above findings, the diagnosis of venous malformations was compatible with BRBNS. As the patient had no dyspnea, dysphagia, or blurred vision, she was given iron supplementation and blood transfusions. Two weeks later, a routine blood test showed that the hemoglobin was 7.7 g/dL. Fecal occult blood test was negative. She was discharged and asked to attend outpatient follow-up monthly.

We describe a case of BRBNS with dominant cutaneous, orbit, superior mediastinum, glottis and gastrointestinal involvement. According to our review of the literature, 20% of patients with BRBNS were from the United States, 15% from Japan, 9% from Spain, 9% from Germany, 6% from China, and 6% from France. There are also reports from other countries; however, the number of cases is much lower, indicating that many races can develop this disease, although BRBNS is rare in Blacks.

Among the 200 cases identified from MEDLINE, the clinical data of 120 cases were analyzed, and cutaneous angiomas were observed in 112 cases which accounted for 93%, and gastrointestinal hemangiomas were observed in 91 cases (76%). Other organs, such as the central nervous system (16 cases, 13%), liver (13, 11%), and muscles (11, 9%) were also involved (Table 1). We found that the involvement of various organs was common in a single patient (87%). The number of sites involved in our patient was 16, and included the scalp, eyelid, orbit, lips, tongue, face, back, upper and lower limbs, buttocks, root of neck, clavicle area, superior mediastinum, glottis, esophagus, colon and anus.

| Organ | Cases | Organ | Cases |

| Skin | 112 | Gastrointestine | 91 |

| Central nervous system | 16 | Liver | 13 |

| Muscle | 11 | Vagina | 4 |

| Spine | 4 | Eyes | 4 |

| Uterus | 3 | Bone | 3 |

| Mediastinum | 3 | Lung | 3 |

| Mesentery | 2 | Joint | 2 |

| Kidney | 2 | Bladder | 2 |

| Thyroid | 2 | Parotid gland | 2 |

| Spleen | 1 | Endobronchial | 1 |

| Gallbladder | 1 | Vocal cord | 1 |

| Pancreas | 1 | Adrenag gland | 1 |

| Peritoneum | 1 | Retroperitoneum | 1 |

| Ampulla of Vater | 1 | Nasopharynx | 1 |

| Pleura | 1 | Heart | 1 |

| Arytenoid cartilage | 1 |

Among the cases reported in the literature, the female-male ratio was approximately 1:1, indicating that there is no sex difference in BRBNS, as reported by Choi et al[5].

The lesions are often present from birth or early childhood[6,7]. The onset of the disease could be traced in 68% (82/120) of the patients reviewed. Among these 82 patients, 30% had BRBNS from birth, in 9% BRBNS started during infancy, in 48% BRBNS started in childhood, in 9% BRBNS started during adolescence, and in 4% BRBNS started in adulthood. The oldest patient reported was 82 years old[8], however, the lesions appeared some years ago, and the youngest was an unborn baby (shown by B-ultrasound in an antenatal examination)[9]. The size and number of lesions grew with time.

The pathogenesis of this disease is uncertain. Although autosomal inheritance of BRBNS has been identified in several familial cases associated with chromosome 9p, the majority are sporadic cases[5,10,11]. According to our review, only six cases had a positive family history. Mogler C found that c-kit was detectable predominantly in smaller vessels within their patient’s tissues, suggesting that the stem cell factor/c-kit signaling axis may be involved in the constant growth of venous malformations[12].

The clinical manifestations vary according to different organ involvement. The cutaneous lesions are usually asymptomatic and some patients complain of painful lesions (5%). Others have reported increased sweating (2%). Pain may be caused by contraction of smooth muscle fibers surrounding the angioma and sweating possibly due to the proximity of the nevi to sweat glands[13,14]. Gastrointestinal hemangiomas may appear in any position from the mouth to the anus[15]. The most common symptoms in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract are bleeding and secondary IDA[16], and may also present with severe complications such as rupture, intestinal torsion, and intussusception[17]. In our review, almost all GI lesions led to chronic bleeding and IDA, seven cases developed intussusception, and one case developed gangrene, volvulus and infarction. Hemangiomas in the brain can lead to cerebral infarction or hemorrhage[6], hemangiomas in the vertebrae can lead to spinal cord compression[18], and hemangiomas in the bronchi can lead to chronic cough[19]. Rare complications of BRBNS have been reported such as blood coagulation disturbance (four cases), thrombocytopenia (three cases), disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (two cases) and the reasons for these complications are unclear.

The diagnosis of BRBNS is based on the presence of characteristic cutaneous lesions with or without GI bleeding and/or the involvement of other organs[20]. Cutaneous angiomas are found on the surface of the skin and can affect the entire body ranging from the scalp to the sole of the foot. The cutaneous lesions are characterized as rubbery, soft, tender and hemorrhagic, easily compressible and promptly refill after compression. The other two types of lesions are large disfiguring cavernous lesions and blue-black irregular macules or papules[2]. Our patient had typical characteristics of the syndrome such as skin lesions, iron deficiency anemia and GI lesions.

For GI lesions, push endoscopic exam is the most important diagnostic method and mucosal resection, argon plasma coagulation, laser photocoagulation, sclerotherapy or band ligation are often necessary[10,21-23]. Capsule endoscopy is a new, non-invasive, reliable imaging technique, well accepted and tolerated by patients, and can be used for the entire small bowel[24]. Capsule endoscopy can also be used for the diagnosis of BRBNS[17,25].

Apart from a physical examination and endoscopy, ultrasonography, radiographic images, CT and magnetic resonance imaging are also useful for the detection of affected visceral organs[20].

Histological examination revealed cavernous venous dilatations, with a thin wall of smooth muscle cells lined by a simple layer of endothelial cells[26]. The diagnosis of BRBNS can be made by visual inspection of the skin lesions and by endoscopy of the GI tract, thus, biopsy is not routinely necessary[27].

BRBNS should be differentiated from hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome), Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, and Maffucci syndrome[5,10,28]. These diseases are all characterized by different forms of vascular malformations. Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome is characterized by bleeding punctiform angiomas, recurrent epistaxis, telangiectasia, and always has a positive family history[14,29]. Maffucci syndrome presents diffuse vascular malformations in the skin and soft tissues, bone malformations and chondrodysplasia[30,31]. Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome is characterized by varicosities, hypertrophia, and soft tissue and bone deformities[32].

The cutaneous lesions are usually asymptomatic and do not require treatment. When lesions occur in higher risk areas of trauma or in joints, treatment may be required, including surgery, sclerotherapy or laser photocoagulation. Some patients also receive treatment due to cosmetic problems[10,13,14,33].

The treatment of GI BRBNS is determined by the extent of intestinal involvement and severity of the disease. If bleeding is minor or intermittent, conservative treatment such as blood transfusions and iron supplementation is recommended due to high recurrence of the disease. For more significant hemorrhages or other complications such as rupture, intestinal torsion, and intussusception, surgical resection, endoscopic sclerosis, and laser photocoagulation have been proposed[10,13,14]. In addition, some doctors suggest surgical treatment as life-long supportive therapy can lower patient quality of life. However, patients must fulfill appropriate indications before surgical resection. Firstly, the number and distribution of GI lesions should be identified; secondly, the GI lesions must be localized[5]. According to the literature, some patients did not respond to corticosteroids and interferon[34-36]. A new treatment method has now been introduced. Yuksekkaya et al[34] first reported the use of low-dose sirolimus (an antiangiogenic agent) in an 8-year-old girl with BRBNS characterized by recurrent severe GI bleeding. The vascular lesions were rapidly reduced after sirolimus treatment, and GI bleeding and muscle hematomas disappeared. No adverse drug reactions due to sirolimus were found after a 20-mo follow-up period.

For lesions located in other organs, the aim of treatment is to control excessive bleeding or compression. If conservative therapy is unsuccessful, resection may be performed.

The prognosis of BRBNS depends on which organs are involved and the extent of involvement. Most patients can live a long life with the disease, but the quality of life is limited due to GI bleeding, oral drug therapy and blood transfusions. In our review, two patients died of BRBNS (one of acute GI bleeding[35] and one of cerebral hemorrhage[8]).

The authors present a rare case of gastrointestinal bleeding in a 45-year-old woman with blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome (BRBNS).

The diagnosis of BRBNS is based on the presence of characteristic cutaneous lesions with or without gastrointestinal lesions.

Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome, Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, and Maffucci syndrome.

Hemoglobin was 3.6 g/dL, mean corpuscular volume 25 pg, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration 35 g/dL, serum ferritin 9 ng/mL, and fecal occult blood test was positive. White blood cell, platelet count, renal and liver function tests were all within normal limits.

Head computed tomography (CT) showed lesions on the scalp, left tempora, and orbit, the brain was normal. Chest CT of the root of the neck, clavicle area and superior mediastinum showed multiple nodular, lumpish lesions, and a soft tissue component that was consistent with a vascular malformation and hemic calculus. Abdominal ultrasonography was normal.

The patient was given iron supplementation and blood transfusions.

A MEDLINE search yielded approximately 200 case reports of blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome published to date. This case is the first female from the Chinese Mainland to be reported in the English literature.

When a patient develops gastrointestinal bleeding and multiple angiomas, a diagnosis of blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome should be considered and an early diagnosis will improve the patient’s quality of life.

This article summarized the epidemiology, clinical manifestation, diagnosis, different diagnosis and therapies of blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome to heighten the awareness of this disease.

P- Reviewer: Aisa AP, Cui J, Stanciu C, Weber FH S- Editor: Ma N L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Gascoyen GG. Case of nevus involving the parotid gland and causing death from suffocation: nevi of the viscera. Trans Pathol Soc Lond. 1860;11:267. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Bean WB. “Blue rubber bleb nevi of the skin and gastrointestinal tract”. Springfield, IL, United States: Charles C Thomas, Vascular Spiders and Related Lesions of the Skin 1958; 178-185. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Terata M, Kikuchi A, Kanasugi T, Fukushima A, Sugiyama T. Association of blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome and placenta previa: report of a case. J Clin Ultrasound. 2013;41:517-520. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wong SH, Lau WY. Blue rubber-bleb nevus syndrome. Dis Colon Rectum. 1982;25:371-374. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Choi KK, Kim JY, Kim MJ, Park H, Choi DW, Choi SH, Heo JS. Radical resection of intestinal blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome. J Korean Surg Soc. 2012;83:316-320. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Krishnappa A, Padmini J. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53:168-170. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Torchia D, Schincaglia E, Palleschi GM. Blue rubber-bleb naevus syndrome arising in the middle age. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64:115-117. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tomelleri G, Cappellari M, Di Matteo A, Zanoni T, Colato C, Bovi P, Moretto G. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome with late onset of central nervous system symptomatic involvement. Neurol Sci. 2010;31:501-504. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Monrigal E, Gallot D, James I, Hameury F, Vanlieferinghen P, Guibaud L. Venous malformation of the soft tissue associated with blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: prenatal imaging and impact on postnatal management. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34:730-732. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rodrigues D, Bourroul ML, Ferrer AP, Monteiro Neto H, Gonçalves ME, Cardoso SR. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome. Rev Hosp Clin Fac Med Sao Paulo. 2000;55:29-34. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Dòmini M, Aquino A, Fakhro A, Tursini S, Marino N, Di Matteo S, Lelli Chiesa P. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome and gastrointestinal haemorrhage: which treatment? Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2002;12:129-133. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Mogler C, Beck C, Kulozik A, Penzel R, Schirmacher P, Breuhahn K. Elevated expression of c-kit in small venous malformations of blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome. Rare Tumors. 2010;2:e36. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Dieckmann K, Maurage C, Faure N, Margulies A, Lorette G, Rudler J, Rolland JC. Combined laser-steroid therapy in blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: case report and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1994;4:372-374. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Gallo SH, McClave SA. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: gastrointestinal involvement and its endoscopic presentation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:72-76. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Dwivedi M, Misra SP. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome causing upper GI hemorrhage: a novel management approach and review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:943-946. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Jain A, Kar P, Chander R, Khandpur S, Jain S, Prabhash K, Gangwal P. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: a cause of gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1998;17:153-154. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Barlas A, Avsar E, Bozbas A, Yegen C. Role of capsule endoscopy in blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome. Can J Surg. 2008;51:E119-E120. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Kamat AS, Aliashkevich AF. Spinal cord compression in a patient with blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome. J Clin Neurosci. 2013;20:467-469. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Gilbey LK, Girod CE. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: endobronchial involvement presenting as chronic cough. Chest. 2003;124:760-763. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Agnese M, Cipolletta L, Bianco MA, Quitadamo P, Miele E, Staiano A. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99:632-635. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Moodley M, Ramdial P. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: case report and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 1993;92:160-162. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Mavrogenis G, Coumaros D, Tzilves D, Rapti E, Stefanidis G, Leroy J, Becmeur F. Cyanoacrylate glue in the management of blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome. Endoscopy. 2011;43 Suppl 2 UCTN:E291-E292. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Nishiyama N, Mori H, Kobara H, Fujihara S, Nomura T, Kobayashi M, Masaki T. Bleeding duodenal hemangioma: morphological changes and endoscopic mucosal resection. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2872-2876. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Muñoz-Navas M. Capsule endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1584-1586. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Pennazio M, Rondonotti E, de Franchis R. Capsule endoscopy in neoplastic diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:5245-5253. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Hasosah MY, Abdul-Wahab AA, Bin-Yahab SA, Al-Rabeaah AA, Rimawi MM, Eyoni YA, Satti MB. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: extensive small bowel vascular lesions responsible for gastrointestinal bleeding. J Paediatr Child Health. 2010;46:63-65. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Atten MJ, Ahmed S, Attar BM, Richter H, Mehta B. Massive pelvic hemangioma in a patient with blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome. South Med J. 2000;93:1122-1125. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Marín-Manzano E, Utrilla López A, Puras Magallay E, Cuesta Gimeno C, Marín-Aznar JL. Cervical cystic lymphangioma in a patient with blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: clinical case report and review of the literature. Ann Vasc Surg. 2010;24:1136.e1-1136.e5. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Shovlin CL, Guttmacher AE, Buscarini E, Faughnan ME, Hyland RH, Westermann CJ, Kjeldsen AD, Plauchu H. Diagnostic criteria for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber syndrome). Am J Med Genet. 2000;91:66-67. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Sakurane HF, Sugai T, Saito T. The association of blue rubber bleb nevus and Maffucci’s syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1967;95:28-36. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 31. | Shepherd V, Godbolt A, Casey T. Maffucci’s syndrome with extensive gastrointestinal involvement. Australas J Dermatol. 2005;46:33-37. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 32. | Arguedas MR, Shore G, Wilcox CM. Congenital vascular lesions of the gastrointestinal tract: blue rubber bleb nevus and Klippel-Trenaunay syndromes. South Med J. 2001;94:405-410. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 33. | Wirth FA, Lowitt MH. Diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous vascular lesions. Am Fam Physician. 1998;57:765-773. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | Yuksekkaya H, Ozbek O, Keser M, Toy H. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: successful treatment with sirolimus. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e1080-e1084. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 96] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Apak H, Celkan T, Ozkan A, Yildiz I, Aydemir EH, Ozdil S, Kuruoglu S. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome associated with consumption coagulopathy: treatment with interferon. Dermatology. 2004;208:345-348. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 36. | Hasan Q, Tan ST, Gush J, Peters SG, Davis PF. Steroid therapy of a proliferating hemangioma: histochemical and molecular changes. Pediatrics. 2000;105:117-120. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |