Published online Sep 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i33.11595

Revised: January 3, 2014

Accepted: April 27, 2014

Published online: September 7, 2014

Processing time: 355 Days and 22.1 Hours

This review analyzes progress and limitations of diagnosis, screening, and therapy of patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. A literature review was carried out by framing the study questions. Vaccination in early childhood has been introduced in most countries and reduces the infection rate. Treatment of chronic hepatitis B can control viral replication in most patients today. It reduces risks for progression and may reverse liver fibrosis. The treatment effect on development of hepatocellular carcinoma is less pronounced when cirrhosis is already present. Despite the success of vaccination and therapy chronic hepatitis B remains a problem since many infected patients do not know of their disease. Although all guidelines recommend screening in high risk groups such as migrants, these suggestions have not been implemented. In addition, the performance of hepatocellular cancer surveillance under real-life conditions is poor. The majority of people with chronic hepatitis B live in resource-constrained settings where effective drugs are not available. Despite the success of vaccination and therapy chronic hepatitis B infection remains a major problem since many patients do not know of their disease. The problems in diagnosis and screening may be overcome by raising awareness, promoting partnerships, and mobilizing resources.

Core tip: This review analyzes progress and limitations of diagnosis, screening, and therapy of patients with chronic hepatitis B. Treatment can control viral replication in most patients today. It reduces risks for progression and may reverse fibrosis. However, screening recommendations have not been implemented, and the performance of hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance is poor. Many patients with chronic hepatitis B live in resource-constrained settings where effective drugs are not available. Despite the therapeutic progress, chronic hepatitis B remains a problem since many patients do not know of their disease. These problems may be overcome by raising awareness, promoting partnerships, and mobilizing resources.

- Citation: Niederau C. Chronic hepatitis B in 2014: Great therapeutic progress, large diagnostic deficit. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(33): 11595-11617

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i33/11595.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i33.11595

Infection with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a major health problem in many countries around the world. It can lead to chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, hepatocellular cancer (HCC), liver transplantation (LTX), and death[1,2]. Great progress has been made in particular in the fields of vaccination and therapy. In many industrialized countries three interferons and six nucleot(s)ides (NUC) are now approved for treatment of chronic hepatitis B[3-5]. Oral administration of recent NUC leads to effective, long-lasting suppression of HBV replication[3-5]. In most patients this treatment is without major side-effects; however, it usually does not lead to HBsAg seroconversion and therefore these drugs have to be given for many years or even indefinitely[3-5]. Interferons may lead to HBsAg seroconversion slightly more often when compared with NUC, but they are associated with more side-effects and cannot be given to patients with advanced or even decompensated cirrhosis[3-5]. Overall, treatment of chronic hepatitis B can effectively control viral replication in the long run in almost all patients today[3-5]. It thereby reduces the risk for progression and deterioration of liver disease[6,7] and can even reverse liver fibrosis and initial cirrhosis[8,9]. The treatment effect on reducing the incidence of HCC is less pronounced in particular when cirrhosis is already present[10-14].

Patients with chronic hepatitis B are in general at risk for development of cirrhosis and HCC[15,16]. This risk is associated mainly with serum HBV-DNA (viral load), length of infection, and degree of fibrosis and inflammation. Most cases of HCC develop in cirrhotic livers, but some cases are also seen in patients without cirrhosis. Mortality in patients with HCC is high in particular when the HCC already presents with symptoms. However, despite screening programmes in patients with HBV infection, HCC is often detected at an advanced stage. NUC can be given in patients with advanced or even decompensated cirrhosis and in patients after LTX[3-5]. Unfortunately, the most effective NUC are not approved or reimbursed in several countries with a high prevalence of HBV for economical reasons[17,18].

Despite the success of vaccination and antiviral therapy, chronic HBV infection remains a major problem since many chronically infected patients are unaware of their disease[19-26]. Most of these patients have been born in countries with a high HBV prevalence and have been infected perinatally or in early childhood. In many industrialized countries the majority of patients with chronic HBV infection are migrants from such countries[27]. Even in most industrialized countries there is no systematic screening of high risk groups such as migrants, and in those with screening programs still many patients with chronic hepatitis B are not diagnosed and treated for various reasons.

The present review will focus both on the great therapeutic progress and on the large deficits in diagnosis and screening. It will not discuss vaccination and LTX in greater detail. Also, co-infections with hepatitis C virus (HCV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and hepatitis D virus (HDV) are not covered systematically.

Globally, more than two billion people are estimated to have been infected with HBV while more than 240-400 million have chronic HBV infection[1,3]. Approximately 600000 to 1 million people die every year from its consequences[1,28-32]. It is estimated that 15%-25% of perinatally infected subjects will die from HBV related liver disease[1,3]. Because of the global importance of chronic HBV and HCV infection, the WHO organizes the “World Hepatitis Day” on July 28 every year to increase awareness and understanding of viral hepatitis[1]. Many patient support groups and scientific organizations participate in this important event.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified three types of regions according to the prevalence of chronic HBV infection: high (> 8%), intermediate (2%-8%), and low (< 2%)[33-35]. High endemicity areas include south-east Asia and the Pacific Basin (excluding Japan, Australia, and New Zealand), sub-Saharan Africa, the Amazon basin, parts of the Middle East, the central Asian Republics, and some countries in Eastern Europe. In these areas 70%-90% of people are infected with HBV before age 40, and 8%-20% are HBV carriers[33]. In countries such as China, Senegal, and Thailand, infection rates are very high in infants and in early childhood with HBsAg prevalence exceeding 25%. In Panama, New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Greenland, and in populations such as Alaskan Indians, infection rates in infants are relatively low and increase rapidly during early childhood[1]. China is estimated to have 120 million people with chronic HBV infection, followed by India and Indonesia with 40 million and 12 million, respectively. North America, Western and Northern Europe, Australia, and parts of South America are considered low endemicity areas with carrier rates < 2% and with < 20% of the population being infected with HBV[1,33,34]. The rest of the world falls into the intermediate range of HBV prevalence with 2%-8% being HBsAg positive[1].

A recent systematic WHO review[36] showed that the prevalence of chronic HBV infection decreased from 1990 to 2005 in most regions of the world, in particular in Central sub-Saharan Africa, Tropical and Central Latin America, South East Asia and Central Europe. The decline of prevalence may be related to the success of HBV immunization. Despite this decrease in prevalence, the absolute number of HBsAg positive persons increased worldwide from 1990 to 2005[36].

Acute HBV infection is a clinical diagnosis characterized by symptoms, high serum aminotransferases, and the presence of HBsAg. Usually IgM antibodies against HBc can be detected and HBV-DNA is present. HBeAg can also be detected in most acute infections, but is of little clinical value in this situation. Chronic infection is defined by the persistence of HBsAg for more that 6 mo[3-5]. Patients with chronic HBV infection are usually not diagnosed by clinical disease but by laboratory means. HBsAg is the major tool for screening and diagnosis of chronic HBV infection. HBV-DNA is usually not measured for screening purposes, but determines the risk for major liver disease and the indication for therapy in HBsAg positive subjects. Screening may also include anti-HBc in order to detect rare cases of HBsAg escape variants. Most recent practice guidelines[3-5] recommend HBV screening in the most important risk groups (Table 1).

| All individuals born in areas with high and intermediate HBV prevalence (> 2 % HBsAg positivity) including immigrants and adopted children |

| Further subjects who belong to a high risk group and should generally be screened |

| Individuals with elevated ALT/AST or others signs of liver disease |

| Household and sexual contacts of HBsAg-positive persons |

| Persons who have ever injected drugs |

| Persons with multiple sexual partners or history of sexually transmitted disease |

| Men who have sex with men |

| Inmates of correctional facilities and jails |

| Individuals infected with HCV or HIV |

| Patients undergoing renal dialysis |

| Patients undergoing chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy |

| All pregnant women |

Acute infection with HBV in early childhood is usually asymptomatic and often results in chronic infection. Infection after childhood is usually self-limited and may lead to acute illness with or without jaundice[37-40]. Incubation time varies from 30-180 d with a mean of 75 d. In highly endemic regions perinatal infection is predominant whereas in regions with low endemicity sexual transmission and IV drug abuse are common modes of infection[38-41]. In most countries blood products are today not a significant risk for HBV infection.

The natural history of chronic HBV infection ranges from an inactive carrier with a good prognosis to progressive chronic hepatitis B with high risk for cirrhosis, LTX, HCC, and liver-associated death[1-5,15,16]. Liver cirrhosis develops in 20%-30% of patients with chronic HBV infection[15,16]. Cirrhosis is associated with an HCC risk of approximately 25%, and HBV infection causes 10%-15% of all HCC cases[42]. HBV infection is therefore also associated with an increase in total mortality[43-45] which is due to HCC in about 50% of deaths. Vaccination may reduce disease burden and mortality in industrialized countries[41,46,47]; however, the increased flow of migrants counteracts this trend[1,2]. The prevalence of the HBeAg-negative form of the disease has increased in many areas including Europe over the last 10 - 20 years due to migration processes and predominance of specific HBV genotypes[1,29-32,48-52].

The complication rate of chronic hepatitis B is associated with the degree of viral replication, inflammation, and fibrosis. The risk for cirrhosis is also increased in the presence of fibrosis, a long disease duration, male gender, co-morbidities like alcohol consumption, diabetes mellitus type 2, obesity, and co-infection in particular with HDV or HIV[53-63]. The community-based REVEAL study showed that presence of HBeAg and the detection of HBV-DNA values > 2000 IU/mL are important risk factors for cirrhosis and HCC in an adult Asian population[60-63]. The incidence of HCC is further increased in the presence of cirrhosis and in patients with elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or ALT flares[56-58]. The 5-years cumulative incidence of cirrhosis ranges from 8%-20% after diagnosis, and the 5-year incidence of decompensation is 20% for untreated patients with compensated cirrhosis[29,32,49-52,64-68]. Decompensated cirrhosis is associated with a 14%-35% 5-years survival rate when patients remain untreated[49-50,65]. The yearly incidence of HCC ranges from 2%-6% when cirrhosis is present[63,58,59].

HBV infection may also cause extrahepatic complications such as membranous glomerulonephritis, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, IgA-mediated nephropathy, polyarthritis, polyarteritis nodosa, bullous pemphigoid, lichen ruber planus, and cryoglobulinaemia which may be associated with neuropathy (further literature in[69]).

A vaccine against hepatitis B has been available since 1982. HBV vaccination has been introduced already in 1982; it is safe and effective. In many countries it is now applied in early childhood in the general population[70].For regions with high HBV prevalence the WHO recommends that all infants receive active and passive HBV vaccination as soon as possible after birth, preferably within 24 h in order to minimize the risk for perinatal infection. The vaccination after birth should be followed by 2 or 3 doses to complete basic vaccination which induces immunological protection in more than 95% of subjects independent of their age for many years and often lifelong. Hepatitis B vaccine is safe and only rarely has side-effects[71-73]. In countries with a low HBV endemicity WHO and local authorities recommend to vaccinate children and adolescents if they have not been previously vaccinated, as well as all adults with an increased risk of HBV infection (Table 2).

| i.v., drug users |

| Potential household and sexual contacts with HBV infected people |

| Subjects frequently requiring blood products, dialysis patients |

| Patients with organ transplantation |

| People who are in prisons and correctional facilities for a longer time |

| People with multiple sexual partners and men who have sex with men |

| Health-care workers with frequent blood contact |

| Travellers who are go to highly endemic regions often or for longer time intervals |

| Clients and staff at institutions for the developmentally disabled |

| Persons with a history of sexually transmitted infection (STI) |

| Person without immunoprotection who undergo chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy |

The WHO states that over one billion doses of hepatitis B vaccine have been used worldwide since 1982. This is a major increase compared with 31 countries in 1992 when the WHO first recommended global HBV vaccination in children. In 2011 a total of 179 WHO Member States regularly vaccinate against hepatitis B, and 93 Member States vaccinated already at birth[1,70]. This progress has decreased perinatal and childhood HBV infection in high endemicity countries from up to 15% to less than 1%. The vaccine is also effective in reducing both the incidence of HCC and mortality from HCC[74-80].

In many countries HBV screening is recommended for all pregnant women. If tested positive for HBsAg, the newborn should receive active and also passive vaccination as soon as possible after birth. In particular the active vaccination markedly reduces the risk for infection from an HBsAg positive mother to her child. The vaccination after birth should be followed by 2 or 3 doses to complete basic vaccination. In pregnant women with a very high HBV replication, it is recommended to consider NUC therapy in the last trimester because in the presence of a high HBV-DNA perinatal infection may occur despite regular vaccination procedures.

For three decades there have been increasingly rigorous blood safety strategies that drastically reduced corresponding HBV infections. In drug users, education and the practice of safe injections significantly reduce the rate of HBV infection. In addition safer sex practices protect against HBV infection; the latter advice is important in particular for sex workers, subjects with multiple sexual partners, and men having sex with men.

Although the recent European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) and American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) guidelines[3,4] mention important unresolved issues and unmet needs in subjects with chronic hepatitis B infection, they do not focus on the largest deficit; i.e., the high rate of HBV infected patients who do not know of their infection and the corresponding failure of implementation of diagnostic and screening recommendations. As stated by EASL and other guidelines[3-5] little is known as yet about the natural history and indication for treatment in immunotolerant patients with normal or almost normal ALT. There is also a need to better identify those patients in whom NUC therapy can be discontinued. Lastly, there is still a need to develop drugs to enhance the as yet unsatisfactory rate in HBsAg seroconversion.

HBsAg prevalence markedly differs not only between continents, but also in smaller regions like Europe; in the general population it ranges between 0.1% and 5.6% among European countries with high levels seen in particular in Greece and Romania[1,25,81-90]. The Centre for Disease Control (CDC) recommends HBsAg screening for subjects born in countries with a HBsAg prevalence > 2%[91,92]. Similar recommendations have been published for Australia and New Zealand by the local Digestive Health Foundation[93]. Indeed in the USA HBsAg prevalence is 5% higher than in many important migrant populations[22]; prevalence of HBsAg was even 17.4% higher in subjects born in Vietnam[22].

Recent studies estimate that a total of 1.3 million foreign-born persons live in the United States with a chronic HBV infection whereas HBV infection is seen in only 300000 persons born in the United States[94]. Despite the fact that there are up to 2 million patients with chronic HBV infections in the United States, less than 50000 people receive prescriptions for HBV antivirals per year (2.5%). This is probably largely due to the fact that many HBV infected persons remain undiagnosed and/or have no access to the health system[17]. Chronic HBV infection is rarely symptomatic. HBV has been called ‘the silent killer’ because infected adults often remain undiagnosed and thus untreated until it is “too late”[2]. Among several European countries only approximately 20%-40% of patients knew of hepatitis B at the time of diagnosis[19-26]. In addition, only 27% knew they belonged to a high risk group[19].

The majority of the 240-350 million people with chronic HBV infection, however, live in resource-constrained settings. Here, the problems of missed diagnoses are certainly even higher when compared to industrialized countries. In addition, effective antiviral drugs are not widely available or utilized for HBV infected persons in these regions. Most antiviral agents used for treatment of HIV infection do not adequately suppress HBV, which is of concern for the 10% of HBV/HIV-coinfected subjects in Africa[18]. HBV/HIV-coinfection is often associated with progressive liver disease[18].

To date routine screening recommendations from the NIH (National Institute of Health), the AALSD, and the CDC for all high-risk groups (Table 2) have been expanded to include individuals born in regions with intermediate (28%) and high prevalence (> 8%). Indeed, 45% of people worldwide live in regions with high prevalence and a further 43% in regions of intermediate endemicity[92]. Although health authorities and scientific organizations recommend to better identification of chronically infected patients born in foreign countries[95,96], as yet such recommendations have not been implemented in systematic or mandatory screening programs.

Chronically infected immigrants are also a reservoir for new infections in host countries[92]. Hepatitis B testing is reliable and inexpensive[92]. HBsAg screening among migrant populations has been shown to be cost-effective[97-100]. Studies have also shown that HBV screening and vaccinating is also effective in infants, children and selected high-risk groups[101].

Similar data have been described for other countries with large migrant populations such as Germany where more than two-thirds of patients with chronic HBV infection have been born in foreign countries with an intermediate or high prevalence of HBsAg[102-107]. Migrants from Turkey account for 22%-33% of all HBV infected people living in Germany. The HBsAg prevalence in the general Turkish population is about 4%; its prevalence may be as high as 7% in Turkish migrants living in Germany[102,103]. Similar data come from the Netherlands, Italy and other European countries[23,107-109]. It has also been shown that HBsAg prevalence is particularly high in large cities and emergency units[110,111]. In all these countries there is no national strategy to implement the screening guidelines[105,106] into daily practice, however.

It is in addition necessary to implement recent guidelines which recommend to screen for HBV (and HCV) in subjects with elevated ALT[3-5]. It has been shown that even this recommendation is not followed by the majority of general practitioners in industrialized countries[112,113], although a large part of undiagnosed HBV infections could be detected by this approach[114]. A recent literature analysis[115] has identified several deficits in migrant screening for viral hepatitis in the European Union (EU). This review and another recent study showed that key factors for a successful screening are support from the local ethnic communities[115,116]. There are obviously also barriers for some migrant populations with already diagnosed HBV infection to have access to treatment and monitoring in industrialized countries[117].

Recent studies showed that knowledge gaps of physicians in hepatitis B diagnosis and management translate into missed opportunities to screen for HBV infection[118-121]. Several studies have shown that antenatal HBsAg screening is cost-effective even in regions with low HBsAg prevalence[122-126]. One study even suggests that general population screening for HBsAg is cost-effective in populations with a prevalence above 0.3%[127]. This study, however, has methodological problems and cannot fully prove its conclusion. Recently it was criticized that immigrants in the United Kingdom are now screened for tuberculosis, but not for HBV infection[128]. In 2007, 194000 of the total of 326000 people with chronic HBV infection in the United Kingdom were born in other countries[129]. In 15 United Kingdom liver centres, 81% of all HBV-infected people were born outside the United Kingdom[130].

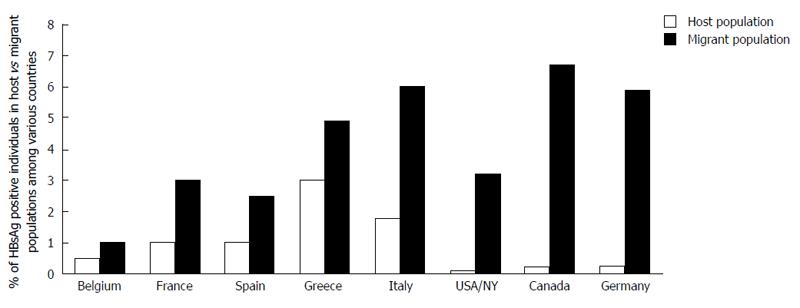

Prevalence of HBsAg in migrants from regions with intermediate or high HBsAg prevalence is 5-90 times higher than that in the host population[27,131-136] (Figure 1) and may range up to 15.4% in Albanian refugees in Greece[137-154]. In asylum seekers and refugees in the United Kingdom the HBsAg prevalence ranged from 5.7% to 9.3%[155]. HBsAg prevalence may be even higher than 10% in some migrant ethnic minorities[146-150]. All studies agree that a large proportion of immigrants would benefit from screening for chronic HBV infection given that recent studies have shown that it is cost-effective to screen for chronic HBV infection at a seroprevalence as low as 1%[97-100]. Furthermore, over half of all migrants were found to be susceptible to HBV and could benefit from HBV immunization programs. It was also shown that HBsAg prevalence is even higher in refugees compared to immigrants probably due to experienced violent acts[137,138]. The largest estimated number of HBV-infected migrants live in the United States (1.6 million), Canada (285000), Germany (284000), Italy (201000), the United Kingdom (193000), and Australia (176000)[27].

Immigrants from high endemicity regions are not routinely screened prior to or after arrival in most low endemicity immigrant-receiving countries[139]. Probably due to a high rate of undetected and untreated HBV infection. HCC incidence and mortality are higher in migrants when compared to subjects born in the host country[140,141]. The proportion of immigrants being screened, however, remains low despite these recent recommendations[99,142].

A recent study identified several problems in prevention and control of HBV infection, such as knowledge and awareness gaps in parts of health care and social service providers, high-risk populations, and in the public and policymakers. Ignorance regarding the seriousness of this health problem results in inadequate public resources allocated to HBV prevention and screening programmes[22,143].

Antenatal screening for HBsAg has been introduced in many countries[156-160]. The proportions of pregnant women screened have usually been higher of 90%[135,139,161-166]. All published analyses showed that screening of all pregnant women for HBsAg in order to prevent perinatal infection is highly cost-effective[122-124]. In most countries and regions including the EU there are directives on blood safety including one for screening for HBV[167-169]. This EU report states that in all 33 reporting member states, each donation is tested for HBV and HCV. Some countries have put some effort into increasing the testing for HBV among drug users[170,171] and in men who have sex with men[171]. A study from the Netherlands showed that only 4% of the eligible migrant population with chronic hepatitis B receives treatment also because there is no active screening done[98]. It was further demonstrated that screening for HBV infection in migrants is highly cost-effective[98].

In 2012, the CDC updated its recommendation[172] that HBV infection alone should not disqualify infected persons from the practice or study of surgery, dentistry, medicine, or allied health fields. For those healthcare professionals requiring oversight, the CDC has published specific suggestions for the composition of expert review panels and the threshold value of serum HBV-DNA considered “safe” for practice (< 1000 IU/mL). For most chronically HBV-infected providers and students who conform to current standards for infection control, HBV infection status alone does not require any curtailing of their practices or supervised learning experiences[172].

There is no specific treatment for acute hepatitis B. There are some hints that patients with severe acute hepatitis B and liver failure may profit from administration of NUC (for further literature please see[173]. Although this concept has not definitely been proven, such treatment is often carried out in many liver centres for patients with acute hepatitis B and liver failure. LTX also still needs to be performed in some patients with fulminant acute hepatitis B.

The best treatment goal as yet is HBsAg seroconversion which is considered the closest outcome to clinical cure[3-5,26,174,175]. However, HBsAg seroconversion is infrequently achieved with the current antiviral drugs[3-5,175,176]. In HBeAg-positive patients seroconversion of HBeAg is also considered a desired goal because it is often associated with a low replicative state and an improvement of prognosis[3-5,177]. The long-term, effective suppression of HBV replication is today the most realistic goal and in general is associated with normalization of ALT, histological improvement of inflammation and fibrosis, and a reduction of complications[3-5].

Indications for treatment slightly differ between recent EASL vs Asian-Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) and AASLD guidelines[3-5] (Table 3). In the EASL guidelines, indications for treatment are generally the same for both HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients; in patients without cirrhosis therapy is considered if HBV-DNA is > 2000 IU/mL for both HBeAg positive and negative patients. In contrast to the EASL consensus, the APASL and AASLD guidelines still differentiate between HBeAg positive and negative patients.

| EASL |

| Indication similar for both HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients |

| Consider therapy if HBV-DNA is > 2000 IU/mL, ALT is > ULN and there is moderate to severe active necroinflammation and/or at least moderate fibrosis on liver biopsy |

| Consider biopsy and therapy separately in immunotolerant patients: HBeAg-positive patients < 30 yr with persistently normal ALT and high HBV-DNA, without evidence of liver disease and family history of HCC or cirrhosis, do not require liver biopsy or therapy. Follow-up is mandatory |

| Consider biopsy or therapy in patients > 30 yr and/or with a family history of HCC or cirrhosis |

| HBeAg-negative patients with persistently normal ALT and HBV-DNA of 2000-20000 IU/mL and without evidence of liver disease do not require liver biopsy or therapy. Follow-up is mandatory |

| Patients with ALT > 2 times ULN and HBV-DNA >20000 IU/ml may start treatment without biopsy |

| Therapy indicated in compensated cirrhosis and detectable HBV-DNA even if ALT is normal |

| Patients with decompensated cirrhosis and any detectable HBV-DNA require urgent therapy |

| APASL |

| HBeAg positive: consider therapy if ALT >2 times ULN and HBV DNA > 20000 IU/mL |

| HBeAg-negative: consider therapy if ALT > 2 times ULN and HBV DNA > 2000 IU/mL |

| Consider therapy in advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis with any ALT level |

| Therapy in all patients with decompensated cirrhosis independent of HBV-DNA |

| Therapy in compensated cirrhosis if HBV-DNA is > 2000 IU/mL |

| In the absence of cirrhosis/severe fibrosis patients with persistently normal or minimally elevated ALT should not be treated irrespective of the height of HBV-DNA. Follow-up is mandatory |

| AASLD |

| HBeAg-positive: consider therapy if ALT >2 times ULN with moderate/severe hepatitis on biopsy and HBV-DNA > 20000 IU/mL |

| In general no therapy if ALT is persistently normal or minimally elevated (< 2 times ULN); consider biopsy in patients with fluctuating /minimally elevated ALT especially in those > 40 yr; consider therapy if there is moderate or severe necroinflammation or significant fibrosis on biopsy |

| HBeAg-negative: consider therapy if HBV-DNA > 20000 IU/mL and ALT > 2 times ULN |

| Consider biopsy if HBV-DNA is 2000-20000 IU/mL and ALT is borderline normal or minimally elevated. Consider therapy if there is moderate/severe inflammation or significant fibrosis on biopsy |

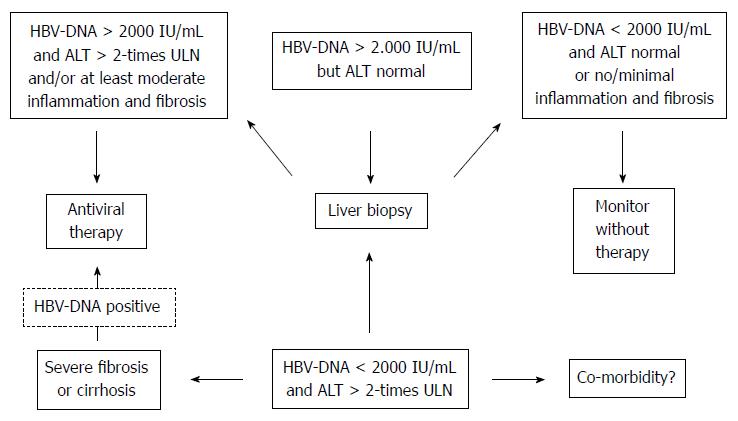

In the APASL and AASLD guidelines[4,5] HBeAg positive patients should be considered for treatment if ALT is greater than two times the upper limit of normal (ULN) or if there is moderate/severe hepatitis on liver biopsy, and if HBV DNA is above 20000 IU/mL (Figure 2). In contrast, in HBeAg-negative patients therapy should be considered if the serum HBV-DNA is above 2000 IU/mL. The APASL and AASLD guidelines recommend consideration for liver biopsy in HBeAg negative patients with HBV-DNA between 2000 and 20000 IU/mL and in those with borderline normal or minimally elevated ALT. In the latter patients, treatment may be initiated if there is moderate or severe inflammation or significant fibrosis on biopsy.

In all guidelines treatment indication is based on the serum HBV-DNA and ALT and on the severity of liver disease which is usually assessed by liver biopsy. Treatment should be considered if HBV-DNA exceeds 2000 IU/mL, ALT levels are above the ULN, and moderate to severe inflammation and/or at least moderate fibrosis is documented by histology. It is mentioned that non-invasive markers may be used instead of liver biopsy once they have been validated in HBV infected patients. Treatment may be initiated also in patients with normal ALT if HBV-DNA is above 2000 IU/mL and if histology shows at least moderate inflammation and fibrosis.

In the EASL guidelines[3], need for liver biopsy and treatment should be considered separately in immunotolerant patients. These patients, defined as HBeAg positive subjects under 30-40 years of age with persistently normal ALT levels and high HBV-DNA levels without evidence of liver disease and without a family history of HCC or cirrhosis, do not require immediate liver biopsy or therapy. These patients should, however, be monitored every 3-6 mo[178,179]. Liver biopsy and therapy should be considered in those immunotolerant patients older than 30-40 years and/or with a family history of HCC or cirrhosis[4-5,180,181]. More frequent monitoring and/or liver biopsy should be performed when ALT levels become elevated[4,182-185].

Thus, differences in the guidelines particularly refer to patients with a HBV-DNA between 2000 and 20000 IU/mL and minimally elevated or almost normal ALT (Figure 2). All guidelines[3-5] actually recommend that such patients should be monitored closely and also should be considered for liver biopsy in order to further clarify the need for treatment. Patients with persistently normal ALT often have minor histological changes and due to the APASL guidelines may not need treatment[5] urgently unless they have advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis[186,187]. All guidelines[3-5] agree that these patients should be monitored every 3-6 mo in order to not to oversee ALT flares. Patients with HBV-DNA > 20000 IU/mL and normal ALT should be monitored even more closely than those with lower HBV-DNA.

HBeAg negative patients with persistently normal ALT and HBV-DNA levels between 2000 and 20000 IU/mL and without any evidence of liver disease also do not require immediate liver biopsy or therapy. Monitoring every 6-12 mo is considered mandatory in this group.

HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients with ALT above two times ULN and serum HBV-DNA above 20000 IU/mL may start treatment even without a liver biopsy. In such patients, liver biopsy may provide additional useful information, but it does not usually change the decision for treatment[3-5]. A non-invasive method for the estimation of the extent of fibrosis and most importantly to confirm or rule out cirrhosis is considered useful in patients who start treatment without liver biopsy. If liver biopsy is not feasible, noninvasive assessment of liver fibrosis is an alternative[4,56,57,188,189]. Age, health status, family history of HCC or cirrhosis, and extrahepatic manifestations also need to be considered when treatment indication is evaluated.

Indications for treatment also slightly differ between recent EASL vs APASL and AASLD guidelines for patients with compensated cirrhosis. In the EASL guidelines these patients must be considered for treatment if HBV-DNA is detectable even though ALT levels are normal. In contrast APASL and AASLD guidelines[4,5] recommend treatment in patients with compensated cirrhosis only if HBV-DNA is above 2000 IU/mL. This difference in guidelines is due to the fact that it is unknown whether cirrhotic patients with a HBV-DNA between 20 and 2000 IU/mL will benefit from antiviral therapy. There is no doubt that cirrhotic patients have the highest risk for decompensation and HCC; thus the author strongly supports the EASL recommendation[3] to treat all cirrhotic patients with detectable HBV-DNA independent of the level of HBV-DNA and ALT.

All guidelines[3-5] recommend that patients with decompensated cirrhosis and detectable HBV-DNA require urgent antiviral treatment with a NUC with a high antiviral efficacy and a high resistance barrier. Such effective antiviral therapy in some patients may lead to improvement in those with decompensated cirrhosis, while other patients still need evaluation for LTX[190,191].

In general, there are two different strategies to treat chronic hepatitis B[3-5]: (1) pegylated Interferon (PEG-IFN) may be used with a finite duration; or (2) NUC are usually given without a finite duration as a long-term treatment.

Although EASL guidelines[3] mention that NUC may also be used for a finite duration, in many patients these substances have to be given for an indefinite duration. EASL guidelines recommend that NUC aimed for a finite treatment should have the highest barrier to resistance to rapidly reduce levels of viremia to undetectable levels and avoid breakthroughs due to HBV resistance[3]. In HBeAg positive patients NUC (as well as interferons) may lead to HBeAg seroconversion which may be associated with a decrease of HBV-DNA to a low replication state. In such patients there may be no need for further antiviral treatment if they remain in a low replicative state after HBeAg seroconversion. In most series, however, less than 30% of patients will have such seroconversion during and after treatment with NUC or interferons[3-5,192-198]; in addition, some seroconverted patients will later either reseroconvert to a positive HBeAg or may have a level of HBV-DNA and ALT requiring further treatment. When HBeAg seroconversion occurs during NUC treatment, therapy should be prolonged for an additional 12 mo[194]; a durable off-treatment response (persistence of anti-HBe seroconversion) may then range from 40%-80%[192-198]. In any case, all patients require close virological monitoring after treatment cessation following HBeAg seroconversion.

There are some hints that HBeAg seroconversions after interferon therapy are more frequent and may be more durable when compared with NUC due to a better immune-mediated control of HBV infection[199-204]. Rates of HBeAg seroconversion due to therapy with PEG-IFN approach 30% and those due to NUC 20%[190,191,205-221]. In patients adherent to treatment, virological remission rates of > 90% can be maintained with ongoing entecavir or tenofovir for up to 8 years[222-224].

Only PEG-IFN α2a is approved for treatment of chronic hepatitis B; it has largely replaced standard interferon (IFN) mainly due to practical and convenience reasons (injection only once weekly). Recent guidelines recommend that PEG-IFN should be given in general for 48 wk, preferably in HBeAg positive patients with good chances for HBeAg seroconversion. It is probably less effective in HBeAg-negative patients. Because of a higher risk of side-effects and inconvenience associated with (PEG)-IFN vs NUC, the decision about the antiviral agent should be discussed with the individual patient in detail. Combinations of interferon or PEG-IFN with NUC has not shown long-term advantage over corresponding mono-therapies[225,226] and are neither approved by the drug agencies nor recommended by guidelines[3-5].

Since interferon often has side-effects, one would like to stop treatment if there is only little probability for response. Such predictors of response to IFN-based therapy include baseline and on-treatment factors. High baseline ALT and low baseline HBV-DNA are associated with a higher response rates; HBV genotypes and IL28B genotypes are also associated with HBeAg and HBsAg seroconversion[191,199,202,224]. On-treatment HBsAg levels and the kinetics of its decline are good predictors of sustained response to Peg-IFN.

HBeAg seroconversions at 6-mo post-treatment are higher in patients with HBsAg levels < 1500 IU/mL at weeks 12 and 24 when compared with those with HBsAg levels > 20000 IU/mL at the same time points (57% vs 16% at week 12, and 54% vs 15% at week 24)[215,222]. Patients without a decline of HBsAg at week 12 had a 82%-97% probability of non-response during post-treatment follow-up[227-231]. Therefore, stopping PEG-IFN therapy may be considered in the latter situation[3,4].

Peg-IFN treatment is probably less useful in HBeAg negative patients since treatment goals are ill defined; only some patients remain in a low replicative state after treatment with PEG-IFN for 48 wk. HBeAg negative patients who are treated with PEG-IFN and fail to achieve any decline in HBsAg levels or have a HBsAg > 20000 IU/mL at week 12 have a very low probability of response; therefore, PEG-IFN therapy may be stopped at that time[232,233].

(PEG)-Interferon(s) are associated with more side-effects than NUC and they are contraindicated in decompensated HBV-associated cirrhosis, autoimmune diseases, severe depression/psychosis, and in pregnant women[3-5].

Today entecavir and tenofovir are the most potent HBV inhibitors with a high barrier to resistance[210,213,221,223,224,234] in treatment-naïve patients. Thus, they can be confidently used as first-line monotherapies[3-5]. Patients with resistance or failure to lamivudine or telbivudine should receive tenofovir if treatment is indicated[3,4].

According to EASL guidelines[3] the further three NUC lamivudine, telbivudine and adefovir may only be used if more potent drugs with high barrier to resistance are not available. Similar to the EASL guidelines[3], AASLD guidelines[5] also state that PEG-IFN, tenofovir or entecavir are preferred for initial treatment. APASL guidelines[4] recommend that the decision as to which agent to be used should be an individual one, based on disease severity, history of flares, hepatic function, the rapidity of drug action, resistance profile, side effects, drug costs, and patient choice. Cost-effectiveness of drug therapy is specific for each country and should be studied independently to guide the choice of drug. The EASL also states that entecavir or tenofovir is the preferred NUC[3].

According to guidelines[3-5], IFN-based therapy is preferred in younger patients. IFN-based therapy has more side effects and requires closer monitoring. For patients with ALT level > 5 times ULN, NUC are recommended if there is a concern about hepatic decompensation[4]. IFN-based therapy is also effective in patients with a higher ALT level if there is no concern about hepatic decompensation. For HBeAg-positive patients with an ALT level between 2 and 5 times ULN, the choice between IFN-based therapy and NUC is less clear, and either agent may be used[4].

Lamivudine was the first NUC approved for treatment of hepatitis B and it is now the most inexpensive agent. However, it is associated with high rates of resistance[235-238]. Thus, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) advises to not use lamivudine any longer for initiation of therapy.

Adefovir was the second NUC approved for treatment of hepatitis B; it is also associated with risks of resistance. Thus, for some time the combination of lamivudine and adefovir was used for patients with resistance problems[213,224,239].

Similar to lamivudine, telbivudine has a relatively low barrier to resistance. Resistance rates are high in particular in patients with high baseline HBV-DNA levels and in those with detectable HBV-DNA after 6 mo of therapy[211,220]; resistance rates to telbivudine are relatively low in patients with a baseline HBV-DNA < 2 × 108 IU/mL for HBeAg-positive and < 2 × 106 IU/mL for HBeAg-negative patients who achieve a negative HBV-DNA 6 mo after beginning treatment[220,240].

In most patients NUC need to be given as a long-term treatment. Only 20%-30% of HBeAg positive patients have an HBeAg seroconversion and some of them may not need long-treatment. HBeAg negative patients require long-term treatment because most of them have a relapse of HBV replication after stopping of therapy. The rate of HBsAg seroconversion in HBeAg negative patients under treatment with NUC is very low. Long-term treatment is also recommended for patients with cirrhosis irrespective of HBeAg status or anti-HBe seroconversion on treatment. EASL guidelines[3] recommend that the most potent drugs with the optimal resistance profile, i.e., tenofovir or entecavir, should be used as first-line mono-therapies. Whatever drug is used, HBV-DNA should effectively be suppressed[3-5].

There are as yet no data to indicate an advantage of de novo combination treatment with NUC in NUC-naïve patients receiving either entecavir or tenofovir[241].

In patients with lamivudine resistance a switch to tenofovir is recommended[3]. In patients with adefovir resistance recommendations consider the prior treatment: If the patient was not previously treated with NUC a switch to entecavir or tenofovir is recommended with entecavir preferred in patients with high viraemia: if the patient had prior lamivudine resistance, a switch to tenofovir and addition of a nucleoside analogue is recommended. In the presence of telbivudine or entecavir resistance a switch to or addition of tenofovir is feasible. Tenofovir resistance has not been described as yet.

The monitoring under NUC treatment is described in detail in current guidelines[3-5]. In general HBV-DNA and other laboratory values need to be checked every 3 mo after after the beginning of therapy. Undetectable HBV-DNA by real-time PCR (i.e., < 10-15 IU/mL) should be achieved to avoid resistance. Once HBV-DNA remains undetectable and ALT normal, the regular interval may be expanded to 6 mo. Treatment with tenofovir or entecavir is preferred in all guidelines because of their potency and minimal risk of resistance[3-5,242,243]. The dose of NUC needs to be adjusted if the estimated creatinine clearance is reduced. Thus, renal function and serum phosphate need to be monitored in particular with adefovir and tenofovir treatment[244].

Patients with cirrhosis require intensively careful monitoring for resistance and flares in order to stabilize patients and to prevent the progression to decompensated liver disease[245,246]. Regression of fibrosis and even reversal of Child A cirrhosis have been reported in patients with prolonged suppression of viral replication[8,9].

Patients with decompensated cirrhosis should be treated in liver centres with a backup of liver transplantation. Antiviral treatment is indicated irrespective of the HBV-DNA level in order to prevent reactivation[190,191,205]. Entecavir or tenofovir should be used since they are effective and safe in this subgroup[190,191,205]. If patients with decompensated cirrhosis show clinical improvement LTX may be avoided. In such patients indefinite treatment with entecavir or tenofovir is recommended. Patients who need LTX should also be treated continuously with entecavir or tenofovir to ensure maximal suppression of HBV-DNA at the time of LTX and thus to reduce the risk of HBV recurrence[247-249]. Long-term monitoring for HCC is necessary despite virological remission since there is still a risk of developing HCC in particular in patients with pre-existing cirrhosis[7,10,250].

HCC is the sixth most common cancer in the world and the third most common cause of cancer mortality[251]. HCC is the most devastating outcome of chronic HBV infection and it is often diagnosed in late stages with little curative chances. Overall 5-years survival is only approximately 5%; in subgroups of HCC patients with an early diagnosis, 5-year survival may be improved to 40%-70%[252]. However, only a small number of patients are diagnosed at stages early enough to have a chance for cure. In population-based U.S. studies, only approximately 10% of HCC patients receive treatment with such a curative approach[253]. Therefore, HCC surveillance has been advocated to detect HCC at an early stage in order to assure a curative approach[3-5,254]. All three current major international HCC guidelines[255-257] and all three major international HBV guidelines[3-5] recommend to perform surveillance for HCC in high-risk populations. These recommendations also consider the cost-effectiveness of such screening which depends on the HCC incidence in the target populations. According to the AASLD guidelines surveillance is cost-effective if the expected HCC risk exceeds 1.5% per year in patients with hepatitis C and 0.2% per year in patients with hepatitis B[257].

The efficacy and cost-effectiveness of surveillance depend on the incidence of HCC in the target population. The HCC risk increases in HBV-infected patients with the degree of fibrosis, age > 40-50 years, duration of infection, level of HBV-DNA, inflammatory activity, co-infections, co-morbidities, and a family history of HCC. Thus, it is rather difficult to exactly identify all subgroups of HBV-infected patients who should be screened[258]. In addition, thresholds for cost-effectiveness of surveillance programs vary according to the economic situation of each country[257]. In any case, all guidelines agree that all patients with HBV infection and cirrhosis or severe fibrosis should be included in HCC surveillance programmes. One large controlled randomized study from China has proved the benefit of surveillance in more than 18000 patients with chronic HBV infection[258]. Surveillance with ultrasound and alpha fetal protein (AFP) measurement every 6 mo reduced HCC mortality by 37% despite of the fact that the compliance of scheduled tests was only 58.2%[258]. Former guidelines recommended HCC surveillance using ultrasound and serum AFP every 6 mo for high-risk HBV-infected individuals (cirrhosis, males, age > 40 years, positive family history of HCC, high viral replication)[31,254].

Most recent studies have shown that the sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound are higher than those of AFP (for detailed literature please see[25-257]. Ultrasound is the most widely used imaging technique used for HCC surveillance with an acceptable sensitivity (58%-89%) and a specificity of up to 90%[259,260]. A meta-analysis including 19 studies showed that ultrasound surveillance detected the majority of HCC tumours before they presented clinically with a sensitivity of 94%[261]. However, ultrasound was less effective for detecting early-stage HCC with a sensitivity of only 63%[262]. In contrast, in a Japanese cohort ultrasound surveillance performed by skilled physicians resulted in a mean size of the detected tumours of < 2 cm with less than 2% of the cases exceeding 3 cm[263]. The widespread use of ultrasound relies on its non-invasiveness, good acceptance by patients, and moderate costs. However, detection of a small HCC in a cirrhotic liver may be difficult even for a skilled investigator[255].

AFP is still the most widely tested tumour marker in HCC. It is known that persistently elevated and increasing AFP values indicate a risk for HCC development[264]. However, AFP is not very useful for surveillance purpose. AFP is often unreliable in patients with chronic hepatitis B because of fluctuating levels which also depend on the inflammatory activity[265]. In addition, a considerable proportion of HCC is not associated with any AFP elevation[266-269]. For diagnostic purposes, an AFP cut-off of 20 ng/mL showed good sensitivity but low specificity, whereas a cut-off of 200 ng/mL was associated with a sensitivity of only 22%[270]. A randomized study[271] and a population-based observational study[265] showed controversial results concerning the use of AFP measurements. The randomized study showed that screening with AFP resulted in earlier diagnosis of HCC, but not in any overall reduction in mortality, because therapy for the patients found by screening was ineffective[271]. The second prospective population-based study determined HCC screening in HBV-infected Alaskan natives with AFP determination done every 6 mo[265]. Subjects with an elevated AFP level were then evaluated for the presence of HCC by ultrasound[265]. In the latter study screening with AFP every 6 mo was effective in detecting most HCC tumours at a resectable stage and significantly prolonged survival rates when compared with historical controls in this population[265].

Most recent studies agree that AFP determination lacks adequate sensitivity and specificity for surveillance as well as for diagnosis[262-264,266-273]. Thus, according to AASLD and EASL guidelines[255,256] surveillance has to be based mainly on ultrasound examination. Better tumour markers need to be developed for HCC surveillance[255,256]. As yet, AFP-L3 and DCP are also not considered useful for routine practice[255,256].

The recommended surveillance interval is still 6 mo[255,256]. Candidates for surveillance include HBV-infected subjects with cirrhosis or severe fibrosis, Asian men > 40 years and Asian women > 50 years, subjects with a family history of HCC, Africans > 20 years, and all subjects > 40 years with persistent or intermittent ALT elevation and/or HBV DNA level > 2000 IU/mL[256]. Screening with AFP should be considered only when ultrasound is not readily available[256,265]. When combined with ultrasound, AFP led only to HCC detection in an additional 6%-8% of cases not identified by ultrasound alone[265]. The best interval of HCC surveillance for HCC depends on the rate of tumour growth and on the tumour incidence in the target population. According to the estimated doubling time of HCC volume[274-277], a 6-mo interval is most often used in clinical practice and recommended by recent guidelines[3-5,255-257]. Some studies comparing the efficacy of 6-mo vs 12-mo intervals showed a similar efficacy[265,278,279] whereas other studies showed a better one with the 6-mo intervals[280,281]. A shorter 3-mo interval has been proposed for patients with a very high HCC risk and by Japanese guidelines[282,283]. In contrast to the latter guideline recommendation, there is no evidence that surveillance with a 3-mo interval is better than with a 6-mo interval[284].

Groups at high risk include all patients with severe fibrosis or cirrhosis in all guidelines [3-6,255-257]. In general, however, all patients with chronic HBV infection are at some risk of HCC development. Unfortunately, the risk of HCC development is less well established in non-cirrhotic individuals[255-257]. In Caucasian patients the HCC risk is mainly restricted to patients with cirrhosis[285,286].According to EASL and AASLD guidelines[255,256] is it unclear whether these patients should have any HCC surveillance. Thus, surveillance is not generally recommended in Caucasian non-cirrhotic patients when viral replication and inflammation are low[255,256,287-291]. The HCC risk, however, is increased also in non-cirrhotic Caucasians with older age, higher viral replication, co-infection (such as HCV, HDV and HIV) and concomitant other liver diseases[255,256]. Such subgroups of adult non-cirrhotic Caucasian patients should also undergo surveillance in addition to all cirrhotic patients[255,256] (Table 4).

| Surveillance all patients with cirrhosis and severe fibrosis |

| Including those treated with NUC |

| Surveillance in individuals with increased HCC risk, even without cirrhosis or severe fibrosis |

| High HBV-DNA |

| Males |

| Age > 40-50 yr (in particular in Asia and Africa) |

| Long duration of infection |

| Significant inflammation |

| Co-infection with HIV, HCV and HDV |

| Co-morbidities (e.g., diabetes mellitus, high alcohol consumption, NASH/NAFDL) |

| For surveillance: Ultrasound done every 6 mo by a skilled physician |

| Determination of AFP (in combination with ultrasound) still recommended by APASL[257], but not by EASL and AASLD guidelines[255-256] |

| AFP is less useful than ultrasound for surveillance of HCC |

In contrast to Causasians, Asian patients without cirrhosis, however, appear to have a higher risk for HCC regardless of the HBV-DNA values[58,287,292,293] and thus should undergo surveillance[256,294]. The annual HCC risk in Asian patients exceeds 0.2% when HBV-DNA is > 2000 IU/mL[295].

The incidence of HCC in male Asian patients starts to exceed 0.2% at age 40[296]; therefore HBV-infected Asian men above age 40 should undergo surveillance; according to AASLD guidelines Asian women should undergo surveillance above age 50[256]. Interestingly, the APASL guidelines recommend general surveillance only in cirrhotic patients[257]. In the presence of a history of a first-degree relative with HCC, surveillance should start at a younger age[296,297] while the exact age still needs to be defined. Africans with hepatitis B also seem to get HCC at a younger age than Caucasians and thus should undergo surveillance at a younger age[298,299].

Risk scores have been developed to better identify those HBV-infected patients who should have surveillance. The score by Yuen et al[300] includes factors such as male gender, older age, higher HBV-DNA levels, core promoter mutations, and cirrhosis. A similar score has been based on the data from the REVEAL study[301,302]. Both scores are not ready to be used in clinical practice[256].

The need for surveillance under long-term antiviral treatment with NUC is not well defined as yet. Several studies suggest that long-term effective NUC treatment will reduce but eliminate the HCC risk which is still present in males, in patients > 40 years of age and in those with cirrhosis[10-14,303-305]. Thus, the latter patients should undergo HCC surveillance even if the HBV-DNA is undetectable and ALT values are normal under long-term NUC treatment[255,256].

In summary, the more recent EASL and AASLD guidelines[255,256] recommend to use ultrasound as the only surveillance tool; AFP is not considered useful for this purpose. Only the recent APASL guideline[257] still recommends to carry out both ultrasound and APF measurement every 6 mo for HCC surveillance in cirrhotic patients with chronic HBV infection.

The performance of HCC surveillance under real-life conditions is poor both for HBV- and HCV-infected individuals. In a recent study of 13002 HCV-infected veterans diagnosed with cirrhosis during 1998-2005, only 12% received annual surveillance in the 3 years following their cirrhosis diagnosis, and less than 50% received a surveillance test in the first year following diagnosis of cirrhosis[306]. At least three retrospective studies among patients with a newly diagnosed HCC reported very low rates of surveillance prior to the HCC diagnosis[307,308]. In one of these studies only 29%[308] of subjects received annual surveillance in the 3 years before the diagnosis of cirrhosis[308]. These deficits likely reflect both knowledge gaps in guidelines as well as logistical problems such as lack of recall systems. Direct patient involvement in HCC surveillance has been shown to improve performance of surveillance[309]. Also, implementation of quality measures incorporating automatic recall systems for providers may improve HCC surveillance[310].

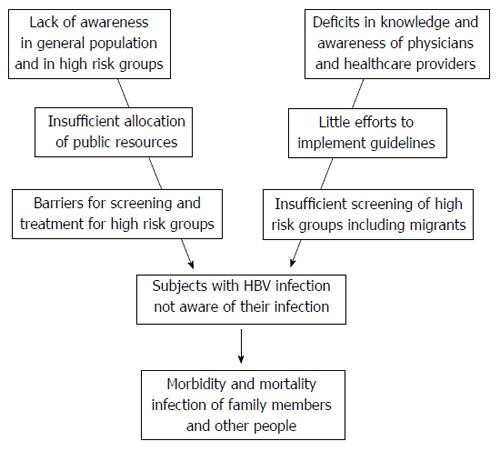

Despite the success of vaccination and the progress of antiviral therapy, chronic HBV infection remains a major health problem since many patients do not know of their disease. There is a corresponding lack of awareness both in the general population and in high risk groups (Figure 3). As yet the allocation of public resources is insufficient to increase the awareness and to implement national and international guidelines. In addition deficits in knowledge and awareness of physicians and healthcare providers have been identified. The performance of HCC surveillance under real-life conditions is also poor. All these problems add to barriers for screening and treatment of high risk groups and finally increase the risk for morbidity and mortality of HBV-infected individuals who, in addition, might infect family members and other people. These problems may be overcome by raising awareness, promoting partnerships, and mobilizing resources.

P- Reviewer: Chen Z, Doganay L, Ferreira CN, Irshad M, Rodriguez-Frias F S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Logan S E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | World Health Organization. Global alert and response: hepatitis B. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/hepatitis/whocdscsrlyo20022/en/index8.html. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Blachier M, Leleu H, Peck-Radosavljevic M, Valla DC, Roudot-Thoraval F. The burden of liver disease in Europe. EASL 2013. Available from: http://www.easl.eu/assets/.../54ae845caec619f_file.pdf. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | European Associations for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57:167-185. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Liaw YF, Kao JH, Piratvuth T, Chan HLY, Chien RN, Liu CJ. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: a 2012 update. Hepatol Int. 2012;6:531-561 [DOI 10.1007/s12072-012-9365-9364]. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:661-662. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2125] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2120] [Article Influence: 141.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Marcellin P, Gane E, Buti M, Afdhal N, Sievert W, Jacobson IM, Washington MK, Germanidis G, Flaherty JF, Schall RA. Regression of cirrhosis during treatment with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for chronic hepatitis B: a 5-year open-label follow-up study. Lancet. 2013;381:468-475. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1228] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1275] [Article Influence: 115.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chang TT, Liaw YF, Wu SS, Schiff E, Han KH, Lai CL, Safadi R, Lee SS, Halota W, Goodman Z. Long-term entecavir therapy results in the reversal of fibrosis/cirrhosis and continued histological improvement in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2010;52:886-893. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 721] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 732] [Article Influence: 52.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Niro GA, Ippolito AM, Fontana R, Valvano MR, Gioffreda D, Iacobellis A, Merla A, Durazzo M, Lotti G, Di Mauro L. Long-term outcome of hepatitis B virus-related Chronic Hepatitis under protracted nucleos(t)ide analogues. J Viral Hepat. 2013;20:502-509. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kim CH, Um SH, Seo YS, Jung JY, Kim JD, Yim HJ, Keum B, Kim YS, Jeen YT, Lee HS. Prognosis of hepatitis B-related liver cirrhosis in the era of oral nucleos(t)ide analog antiviral agents. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1589-1595. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Papatheodoridis GV, Manolakopoulos S, Touloumi G, Vourli G, Raptopoulou-Gigi M, Vafiadis-Zoumbouli I, Vasiliadis T, Mimidis K, Gogos C, Ketikoglou I. Virological suppression does not prevent the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B patients with cirrhosis receiving oral antiviral(s) starting with lamivudine monotherapy: results of the nationwide HEPNET. Greece cohort study. Gut. 2011;60:1109-1116. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 141] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jin YJ, Shim JH, Lee HC, Yoo DJ, Kim KM, Lim YS, Suh DJ. Suppressive effects of entecavir on hepatitis B virus and hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:1380-1388. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hosaka T, Suzuki F, Kobayashi M, Seko Y, Kawamura Y, Sezaki H, Akuta N, Suzuki Y, Saitoh S, Arase Y. Long-term entecavir treatment reduces hepatocellular carcinoma incidence in patients with hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 2013;58:98-107. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 519] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 507] [Article Influence: 46.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zoutendijk R, Reijnders JG, Zoulim F, Brown A, Mutimer DJ, Deterding K, Hofmann WP, Petersen J, Fasano M, Buti M. Virological response to entecavir is associated with a better clinical outcome in chronic hepatitis B patients with cirrhosis. Gut. 2013;62:760-765. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 136] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Singal AK, Salameh H, Kuo YF, Fontana RJ. Meta-analysis: the impact of oral anti-viral agents on the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:98-106. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 121] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cadranel JF, Lahmek P, Causse X, Bellaiche G, Bettan L, Fontanges T, Medini A, Henrion J, Chousterman M, Condat B. Epidemiology of chronic hepatitis B infection in France: risk factors for significant fibrosis--results of a nationwide survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:565-576. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Mota A, Areias J, Cardoso MF. Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis among patients with hepatitis B virus infection in northern Portugal with reference to the viral genotypes. J Med Virol. 2011;83:71-77. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Larsen JJ. alpha And beta-adrenoceptors in the detrusor muscle and bladder base of the pig and beta-adrenoceptors in the detrusor muscle of man. Br J Pharmacol. 1979;65:215-222. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Almasio PL, Craxì A. Management of hepatitis B virus infection in the underprivileged world. Liver Int. 2011;31:749-750. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | European Liver Patients Association. Report on hepatitis patient self-help in Europe; 2010. Available from: http://www.hepbcppa.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/Report-on-Patient-Self-Help.pdf. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Piorkowsky NY. Europe’s hepatitis challenge: defusing the “viral time bomb”. J Hepatol. 2009;51:1068-1073. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | McPherson S, Valappil M, Moses SE, Eltringham G, Miller C, Baxter K, Chan A, Shafiq K, Saeed A, Qureshi R. Targeted case finding for hepatitis B using dry blood spot testing in the British-Chinese and South Asian populations of the North-East of England. J Viral Hepat. 2013;20:638-644. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cohen C, Holmberg SD, McMahon BJ, Block JM, Brosgart CL, Gish RG, London WT, Block TM. Is chronic hepatitis B being undertreated in the United States? J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:377-383. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Richter C, Beest GT, Sancak I, Aydinly R, Bulbul K, Laetemia-Tomata F, De Leeuw M, Waegemaekers T, Swanink C, Roovers E. Hepatitis B prevalence in the Turkish population of Arnhem: implications for national screening policy? Epidemiol Infect. 2012;140:724-730. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Meffre C, Le Strat Y, Delarocque-Astagneau E, Dubois F, Antona D, Lemasson JM, Warszawski J, Steinmetz J, Coste D, Meyer JF. Prevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infections in France in 2004: social factors are important predictors after adjusting for known risk factors. J Med Virol. 2010;82:546-555. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 159] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hahné SJ, De Melker HE, Kretzschmar M, Mollema L, Van Der Klis FR, Van Der Sande MA, Boot HJ. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection in The Netherlands in 1996 and 2007. Epidemiol Infect. 2012;140:1469-1480. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lin SY, Chang ET, So SK. Stopping a silent killer in the underserved asian and pacific islander community: a chronic hepatitis B and liver cancer prevention clinic by medical students. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2009;10:383-386. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Rossi C, Shrier I, Marshall L, Cnossen S, Schwartzman K, Klein MB, Schwarzer G, Greenaway C. Seroprevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection and prior immunity in immigrants and refugees: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44611. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 106] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Viral Hepatitis Prevention Board. The clock is running. 1997: Deadline for integrating hepatitis B vaccinations into all national immunization programmes, 1996 (Fact Sheet VHPB/ 1996/1. Available from: http://hgins.uia.ac.be/esoc/VHPB/vhfs1.html. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Ganem D, Prince AM. Hepatitis B virus infection--natural history and clinical consequences. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1118-1129. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Hoofnagle JH, Doo E, Liang TJ, Fleischer R, Lok AS. Management of hepatitis B: summary of a clinical research workshop. Hepatology. 2007;45:1056-1075. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 31. | Liaw YF. Prevention and surveillance of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2005;25 Suppl 1:40-47. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 32. | Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2007;45:507-539. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 33. | Hollinger FB, Liang TJ. Hepatitis B Virus. Fields Virology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams Wilkins 2001; 2971-3036. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | Mahoney FJ, Kane M. Hepatitis B vaccine. Vaccines. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company 1999; 158-182. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 35. | Viral Hepatitis Prevention Board. Universal HB immunization by 1997: where are we now? 1998 (Fact Sheet VHPB/ 1998/2). Available from: http://hgins.uia.ac.be/esoc/VHPB/vhfs1.html. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 36. | Ott JJ, Stevens GA, Groeger J, Wiersma ST. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection: new estimates of age-specific HBsAg seroprevalence and endemicity. Vaccine. 2012;30:2212-2219. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1217] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1266] [Article Influence: 105.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Hyams KC. Risks of chronicity following acute hepatitis B virus infection: a review. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:992-1000. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 38. | Custer B, Sullivan SD, Hazlet TK, Iloeje U, Veenstra DL, Kowdley KV. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:S158-S168. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 381] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 394] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Redd JT, Baumbach J, Kohn W, Nainan O, Khristova M, Williams I. Patient-to-patient transmission of hepatitis B virus associated with oral surgery. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1311-1314. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 64] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Alter MJ. Epidemiology and prevention of hepatitis B. Semin Liver Dis. 2003;23:39-46. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Van Damme P. Hepatitis B: vaccination programmes in Europe--an update. Vaccine. 2001;19:2375-2379. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 42. | Hatzakis A, Wait S, Bruix J, Buti M, Carballo M, Cavaleri M, Colombo M, Delarocque-Astagneau E, Dusheiko G, Esmat G. The state of hepatitis B and C in Europe: report from the hepatitis B and C summit conference*. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18 Suppl 1:1-16. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 155] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Duberg AS, Törner A, Davidsdóttir L, Aleman S, Blaxhult A, Svensson A, Hultcrantz R, Bäck E, Ekdahl K. Cause of death in individuals with chronic HBV and/or HCV infection, a nationwide community-based register study. J Viral Hepat. 2008;15:538-550. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 52] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | García-Fulgueiras A, García-Pina R, Morant C, García-Ortuzar V, Génova R, Alvarez E. Hepatitis C and hepatitis B-related mortality in Spain. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:895-901. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Marcellin P, Pequignot F, Delarocque-Astagneau E, Zarski JP, Ganne N, Hillon P, Antona D, Bovet M, Mechain M, Asselah T. Mortality related to chronic hepatitis B and chronic hepatitis C in France: evidence for the role of HIV coinfection and alcohol consumption. J Hepatol. 2008;48:200-207. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 46. | Salleras L, Domínguez A, Bruguera M, Plans P, Espuñes J, Costa J, Cardeñosa N, Plasència A. Seroepidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection in pregnant women in Catalonia (Spain). J Clin Virol. 2009;44:329-332. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Zacharakis G, Kotsiou S, Papoutselis M, Vafiadis N, Tzara F, Pouliou E, Maltezos E, Koskinas J, Papoutselis K. Changes in the epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection following the implementation of immunisation programmes in northeastern Greece. Euro Surveill. 2009;14. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 48. | Fattovich G. Natural history and prognosis of hepatitis B. Semin Liver Dis. 2003;23:47-58. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 49. | McMahon BJ. Epidemiology and natural history of hepatitis B. Semin Liver Dis. 2005;25 Suppl 1:3-8. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 50. | Hadziyannis SJ, Papatheodoridis GV. Hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B: natural history and treatment. Semin Liver Dis. 2006;26:130-141. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 51. | Zarski JP, Marcellin P, Leroy V, Trepo C, Samuel D, Ganne-Carrie N, Barange K, Canva V, Doffoel M, Cales P. Characteristics of patients with chronic hepatitis B in France: predominant frequency of HBe antigen negative cases. J Hepatol. 2006;45:355-360. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 52. | Funk ML, Rosenberg DM, Lok AS. World-wide epidemiology of HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B and associated precore and core promoter variants. J Viral Hepat. 2002;9:52-61. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 53. | Liaw YF, Tai DI, Chu CM, Chen TJ. The development of cirrhosis in patients with chronic type B hepatitis: a prospective study. Hepatology. 1998;8:493-496. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 54. | Lin SM, Yu ML, Lee CM, Chien RN, Sheen IS, Chu CM, Liaw YF. Interferon therapy in HBeAg positive chronic hepatitis reduces progression to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2007;46:45-52. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 55. | Park BK, Park YN, Ahn SH, Lee KS, Chon CY, Moon YM, Park C, Han KH. Long-term outcome of chronic hepatitis B based on histological grade and stage. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:383-388. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 56. | Wu CF, Yu MW, Lin CL, Liu CJ, Shih WL, Tsai KS, Chen CJ. Long-term tracking of hepatitis B viral load and the relationship with risk for hepatocellular carcinoma in men. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:106-112. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 57. | Chen CF, Lee WC, Yang HI, Chang HC, Jen CL, Iloeje UH, Su J, Hsiao CK, Wang LY, You SL. Changes in serum levels of HBV DNA and alanine aminotransferase determine risk for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1240-128, 1240-128. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Yang HI, Lu SN, Liaw YF, You SL, Sun CA, Wang LY, Hsiao CK, Chen PJ, Chen DS, Chen CJ. Hepatitis B e antigen and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:168-174. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 59. | Iloeje UH, Yang HI, Su J, Jen CL, You SL, Chen CJ. Predicting cirrhosis risk based on the level of circulating hepatitis B viral load. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:678-686. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 60. | Chen CJ, Yang HI, Su J, Jen CL, You SL, Lu SN, Huang GT, Iloeje UH. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma across a biological gradient of serum hepatitis B virus DNA level. JAMA. 2006;295:65-73. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 61. | Chen CL, Yang HI, Yang WS, Liu CJ, Chen PJ, You SL, Wang LY, Sun CA, Lu SN, Chen DS. Metabolic factors and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma by chronic hepatitis B/C infection: a follow-up study in Taiwan. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:111-121. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 386] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 410] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Yu MW, Shih WL, Lin CL, Liu CJ, Jian JW, Tsai KS, Chen CJ. Body-mass index and progression of hepatitis B: a population-based cohort study in men. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5576-5582. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 96] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Young EW, Koch PB, Preston DB. AIDS and homosexuality: a longitudinal study of knowledge and attitude change among rural nurses. Public Health Nurs. 1989;6:189-196. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 64. | Fattovich G, Bortolotti F, Donato F. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B: special emphasis on disease progression and prognostic factors. J Hepatol. 2008;48:335-352. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 65. | Fattovich G, Olivari N, Pasino M, D’Onofrio M, Martone E, Donato F. Long-term outcome of chronic hepatitis B in Caucasian patients: mortality after 25 years. Gut. 2008;57:84-90. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 66. | Fattovich G, Stroffolini T, Zagni I, Donato F. Hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: incidence and risk factors. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S35-S50. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 67. | Chen YC, Chu CM, Yeh CT, Liaw YF. Natural course following the onset of cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B: a long-term follow-up study. Hepatol Int. 2007;1:267-273. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |